T ores of a lifetime. The poet, writer, creator of the first Russian literary magazine and the last historiographer of Russia worked on the work of 12 volumes for more than twenty years. He managed to give a historical work a “light style” and create a real historical bestseller of his time. Natalya Letnikova studied the history of the creation of the famous multi-volume book.

From travel writing to studying history. The author of “Letters of a Russian Traveler”, “Poor Lisa”, “Marfa Posadnitsa”, a successful publisher of “Moscow Journal” and “Bulletin of Europe” became seriously interested in history at the beginning of the 19th century. Studying chronicles and rare manuscripts, I decided to combine invaluable knowledge into one work. I set the task - to create a complete printed, publicly accessible presentation of Russian history.

Historiographer of the Russian Empire. Karamzin was appointed to the honorary position of the country's chief historian by Emperor Alexander I. The writer received an annual pension of two thousand rubles and access to all libraries. Karamzin without hesitation left Vestnik, which brought in three times as much income, and devoted his life to “The History of the Russian State.” As Prince Vyazemsky noted, “he took monastic vows as a historian.” Karamzin preferred archives to secular salons, and studying documents to invitations to balls.

Historical knowledge and literary style. Not just a statement of facts mixed with dates, but a highly artistic historical book for a wide range of readers. Karamzin worked not only with primary sources, but also with syllables. The author himself called his work a “historical poem.” The scientist hid extracts, quotes, retellings of documents in notes - in fact, Karamzin created a book within a book for those who are especially interested in history.

First historical bestseller. The author sent eight volumes to print only thirteen years after the start of work. Three printing houses were involved: military, senate, and medical. Proofreading took up the lion's share of time. Three thousand copies were published a year later - at the beginning of 1818. Historical volumes were sold out no worse than sensational romance novels: the first edition sold out to readers in just a month.

Scientific discoveries in the meantime. While working, Nikolai Mikhailovich discovered truly unique sources. It was Karamzin who found the Ipatiev Chronicle. The notes of volume VI include excerpts from “Walking across Three Seas” by Afanasy Nikitin. “Until now, geographers did not know that the honor of one of the oldest described European journeys to India belongs to Russia of the Ioannian century... It (the journey) proves that Russia in the 15th century had its own Taverniers and Chardenis, less enlightened, but equally courageous and enterprising.”, wrote the historian.

Pushkin about the work of Karamzin. “Everyone, even secular women, rushed to read the history of their fatherland, hitherto unknown to them. She was a new discovery for them. Ancient Russia seemed to be found by Karamzin, like America by Columbus. They didn't talk about anything else for a while..."- wrote Pushkin. Alexander Sergeevich dedicated the tragedy “Boris Godunov” to the memory of the historiographer; he also drew material for his work from Karamzin’s “History”.

Assessment at the highest state level. Alexander I not only gave Karamzin the broadest powers to read “all ancient manuscripts relating to Russian antiquities” and financial support. The Emperor personally financed the first edition of the History of the Russian State. By order of the highest order, the book was distributed to ministries and embassies. The accompanying letter stated that sovereigns and diplomats are obliged to know their history.

Whatever the event. We were waiting for the release of the new book. The second edition of the eight-volume edition was published a year later. Each subsequent volume became an event. Historical facts were discussed in society. So volume IX, dedicated to the era of Ivan the Terrible, became a real shock. “Well, Grozny! Well, Karamzin! I don’t know what to be more surprised at, the tyranny of John or the gift of our Tacitus.”“, wrote the poet Kondraty Ryleev, noting both the horrors of the oprichnina and the wonderful style of the historian.

The last historiographer of Russia. The title appeared under Peter the Great. The honorary title was awarded to a native of Germany, archivist and author of “History of Siberia” Gerhard Miller, also famous for “Miller’s portfolios”. The author of “The History of Russia from Ancient Times”, Prince Mikhail Shcherbatov, held a high position. Sergei Solovyov, who dedicated 30 years to his historical work, and Vladimir Ikonnikov, a major historian of the early twentieth century, applied for it, but, despite petitions, they never received the title. So Nikolai Karamzin remained the last historiographer of Russia.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin

"History of the Russian State"

Preface

History, in a sense, is the sacred book of peoples: the main, necessary; a mirror of their existence and activity; the tablet of revelations and rules; the covenant of ancestors to posterity; addition, explanation of the present and example of the future.

Rulers and Legislators act according to the instructions of History and look at its pages like sailors at drawings of the seas. Human wisdom needs experience, and life is short-lived. One must know how from time immemorial rebellious passions agitated civil society and in what ways the beneficial power of the mind curbed their stormy desire to establish order, harmonize the benefits of people and give them the happiness possible on earth.

But an ordinary citizen should also read History. She reconciles him with the imperfection of the visible order of things, as with an ordinary phenomenon in all centuries; consoles in state disasters, testifying that similar ones have happened before, even worse ones have happened, and the State was not destroyed; it nourishes a moral feeling and with its righteous judgment disposes the soul towards justice, which affirms our good and the harmony of society.

Here is the benefit: how much pleasure for the heart and mind! Curiosity is akin to man, both the enlightened and the wild. At the glorious Olympic Games, the noise fell silent, and the crowds remained silent around Herodotus, reading the legends of the centuries. Even without knowing the use of letters, peoples already love History: the old man points the young man to a high grave and tells about the deeds of the Hero lying in it. The first experiments of our ancestors in the art of literacy were devoted to Faith and Scripture; Darkened by a thick shadow of ignorance, the people greedily listened to the tales of the Chroniclers. And I like fiction; but for complete pleasure one must deceive oneself and think that they are the truth. History, opening the tombs, raising the dead, putting life into their hearts and words into their mouths, re-creating Kingdoms from corruption and imagining a series of centuries with their distinct passions, morals, and deeds, expands the boundaries of our own existence; by its creative power we live with people of all times, we see and hear them, we love and hate them; Without even thinking about the benefits, we already enjoy the contemplation of diverse cases and characters that occupy the mind or nourish sensitivity.

If any History, even unskillfully written, is pleasant, as Pliny says: how much more domestic. The true Cosmopolitan is a metaphysical being or such an extraordinary phenomenon that there is no need to talk about him, neither to praise nor to condemn him. We are all citizens, in Europe and in India, in Mexico and in Abyssinia; Everyone’s personality is closely connected with the fatherland: we love it because we love ourselves. Let the Greeks and Romans captivate the imagination: they belong to the family of the human race and are not strangers to us in their virtues and weaknesses, glory and disasters; but the name Russian has a special charm for us: my heart beats even stronger for Pozharsky than for Themistocles or Scipio. World History decorates the world for the mind with great memories, and Russian History decorates the fatherland where we live and feel. How attractive are the banks of the Volkhov, Dnieper, and Don, when we know what happened on them in ancient times! Not only Novgorod, Kyiv, Vladimir, but also the huts of Yelets, Kozelsk, Galich become curious monuments and silent objects - eloquent. The shadows of past centuries paint pictures before us everywhere.

In addition to the special dignity for us, the sons of Russia, its chronicles have something in common. Let us look at the space of this only Power: thought becomes numb; Rome in its greatness could never equal her, dominating from the Tiber to the Caucasus, the Elbe and the African sands. Isn’t it amazing how lands separated by eternal natural barriers, immeasurable deserts and impenetrable forests, cold and hot climates, like Astrakhan and Lapland, Siberia and Bessarabia, could form one Power with Moscow? Is the mixture of its inhabitants less wonderful, diverse, diverse and so distant from each other in degrees of education? Like America, Russia has its Wild Ones; like other European countries it shows the fruits of long-term civic life. You don’t need to be Russian: you just need to think in order to read with curiosity the traditions of the people who, with courage and courage, gained dominance over a ninth part of the world, discovered countries hitherto unknown to anyone, bringing them into the general system of Geography and History, and enlightened them with the Divine Faith, without violence , without the atrocities used by other zealots of Christianity in Europe and America, but only an example of the best.

We agree that the acts described by Herodotus, Thucydides, Livy are more interesting for anyone who is not Russian, representing more spiritual strength and a lively play of passions: for Greece and Rome were people's Powers and more enlightened than Russia; however, we can safely say that some cases, pictures, characters of our History are no less curious than the ancients. These are the essence of the exploits of Svyatoslav, the thunderstorm of Batu, the uprising of the Russians at Donskoy, the fall of Novagorod, the capture of Kazan, the triumph of national virtues during the Interregnum. Giants of the twilight, Oleg and son Igor; the simple-hearted knight, the blind Vasilko; friend of the fatherland, benevolent Monomakh; Mstislavs Brave, terrible in battle and an example of kindness in the world; Mikhail Tversky, so famous for his magnanimous death, the ill-fated, truly courageous, Alexander Nevsky; The hero, the young man, the conqueror of Mamaev, in the lightest outline, has a strong effect on the imagination and heart. The reign of John III alone is a rare treasure for history: at least I don’t know a monarch more worthy to live and shine in its sanctuary. The rays of his glory fall on the cradle of Peter - and between these two Autocrats the amazing John IV, Godunov, worthy of his happiness and misfortune, the strange False Dmitry, and behind the host of valiant Patriots, Boyars and citizens, the mentor of the throne, High Hierarch Philaret with the Sovereign Son, a light-bearer in the darkness our state disasters, and Tsar Alexy, the wise father of the Emperor, whom Europe called Great. Either all of New History should remain silent, or Russian History should have the right to attention.

I know that the battles of our specific civil strife, rattling incessantly in the space of five centuries, are of little importance to the mind; that this subject is neither rich in thoughts for the Pragmatist, nor in beauty for the painter; but History is not a novel, and the world is not a garden where everything should be pleasant: it depicts the real world. We see majestic mountains and waterfalls, flowering meadows and valleys on earth; but how many barren sands and dull steppes! However, travel is generally kind to a person with a lively feeling and imagination; In the very deserts there are beautiful species.

A. Venetsianov "Portrait of N.M. Karamzin"

“I was looking for a path to the truth,

I wanted to know the reason for everything...” (N.M. Karamzin)

“History of the Russian State” was the last and unfinished work of the outstanding Russian historian N.M. Karamzin: a total of 12 volumes of research were written, Russian history was presented up to 1612.

Karamzin developed an interest in history in his youth, but there was a long way to go before he was called as a historian.

From the biography of N.M. Karamzin

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin born in 1766 in the family estate of Znamenskoye, Simbirsk district, Kazan province, in the family of a retired captain, an average Simbirsk nobleman. Received home education. Studied at Moscow University. He served for a short time in the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment of St. Petersburg; it was during this time that his first literary experiments dated back.

After retiring, he lived for some time in Simbirsk and then moved to Moscow.

In 1789, Karamzin left for Europe, where he visited I. Kant in Konigsberg, and in Paris he witnessed the Great French Revolution. Returning to Russia, he publishes “Letters of a Russian Traveler,” which make him a famous writer.

Writer

“Karamzin’s influence on literature can be compared with Catherine’s influence on society: he made literature humane”(A.I. Herzen)

Creativity N.M. Karamzin developed in line with sentimentalism.

V. Tropinin "Portrait of N.M. Karamzin"

Literary direction sentimentalism(from fr.sentiment- feeling) was popular in Europe from the 20s to the 80s of the 18th century, and in Russia - from the end of the 18th to the beginning of the 19th century. J.-J. is considered the ideologist of sentimentalism. Ruso.

European sentimentalism penetrated into Russia in the 1780s and early 1790s. thanks to translations of Goethe's Werther, novels by S. Richardson and J.-J. Rousseau, who were very popular in Russia:

She liked novels early on;

They replaced everything for her.

She fell in love with deceptions

And Richardson and Russo.

Pushkin is talking here about his heroine Tatyana, but all the girls of that time were reading sentimental novels.

The main feature of sentimentalism is that attention is primarily paid to the spiritual world of a person; feelings come first, not reason and great ideas. The heroes of works of sentimentalism have innate moral purity and innocence; they live in the lap of nature, love it and are merged with it.

Such a heroine is Liza from Karamzin’s story “Poor Liza” (1792). This story was a huge success among readers, it was followed by numerous imitations, but the main significance of sentimentalism and in particular Karamzin’s story was that in such works the inner world of a simple person was revealed, which evoked the ability to empathize in others.

In poetry, Karamzin was also an innovator: the previous poetry, represented by the odes of Lomonosov and Derzhavin, spoke the language of the mind, and Karamzin’s poems spoke the language of the heart.

N.M. Karamzin - reformer of the Russian language

He enriched the Russian language with many words: “impression”, “falling in love”, “influence”, “entertaining”, “touching”. Introduced the words “era”, “concentrate”, “scene”, “moral”, “aesthetic”, “harmony”, “future”, “catastrophe”, “charity”, “freethinking”, “attraction”, “responsibility” ", "suspiciousness", "industrial", "sophistication", "first-class", "humane".

His language reforms caused heated controversy: members of the “Conversation of Lovers of the Russian Word” society, headed by G. R. Derzhavin and A. S. Shishkov, adhered to conservative views and opposed the reform of the Russian language. In response to their activities, the literary society “Arzamas” was formed in 1815 (it included Batyushkov, Vyazemsky, Zhukovsky, Pushkin), which ironized the authors of “Conversation” and parodied their works. The literary victory of “Arzamas” over “Conversation” was won, which strengthened the victory of Karamzin’s linguistic changes.

Karamzin also introduced the letter E into the alphabet. Before this, the words “tree”, “hedgehog” were written like this: “yolka”, “yozh”.

Karamzin also introduced the dash, one of the punctuation marks, into Russian writing.

Historian

In 1802 N.M. Karamzin wrote the historical story “Marfa the Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novagorod,” and in 1803 Alexander I appointed him to the post of historiographer, thus, Karamzin devoted the rest of his life to writing “The History of the Russian State,” essentially finishing with fiction.

Studying manuscripts of the 16th century, Karamzin discovered and published in 1821 Afanasy Nikitin’s “Walking across Three Seas.” In this regard, he wrote: “... while Vasco da Gamma was only thinking about the possibility of finding a way from Africa to Hindustan, our Tverite was already a merchant on the banks of the Malabar”(historical region in South India). In addition, Karamzin was the initiator of the installation of a monument to K. M. Minin and D. M. Pozharsky on Red Square and took the initiative to erect monuments to outstanding figures of Russian history.

"History of the Russian State"

Historical work by N.M. Karamzin

This is a multi-volume work by N. M. Karamzin, describing Russian history from ancient times to the reign of Ivan IV the Terrible and the Time of Troubles. Karamzin’s work was not the first in describing the history of Russia; before him there were already historical works by V.N. Tatishchev and M.M. Shcherbatov.

But Karamzin’s “History” had, in addition to historical, high literary merits, including due to the ease of writing; it attracted not only specialists to Russian history, but also simply educated people, which greatly contributed to the formation of national self-awareness and interest in the past. A.S. Pushkin wrote that “everyone, even secular women, rushed to read the history of their fatherland, hitherto unknown to them. She was a new discovery for them. Ancient Russia seemed to be found by Karamzin, like America by Columbus.”

It is believed that in this work Karamzin nevertheless showed himself more not as a historian, but as a writer: “History” is written in a beautiful literary language (by the way, in it Karamzin did not use the letter Y), but the historical value of his work is unconditional, because . the author used manuscripts that were first published by him and many of which have not survived to this day.

Working on “History” until the end of his life, Karamzin did not have time to finish it. The text of the manuscript breaks off at the chapter “Interregnum 1611-1612”.

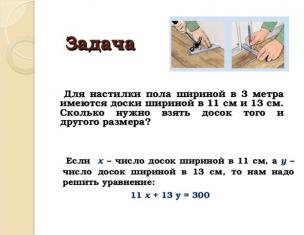

Work by N.M. Karamzin on “History of the Russian State”

In 1804, Karamzin retired to the Ostafyevo estate, where he devoted himself entirely to writing “History.”

Ostafyevo Estate

Ostafyevo- estate of Prince P. A. Vyazemsky near Moscow. It was built in 1800-07. the poet's father, Prince A.I. Vyazemsky. The estate remained in the possession of the Vyazemskys until 1898, after which it passed into the possession of the Sheremetev counts.

In 1804, A.I. Vyazemsky invited his son-in-law, N.M., to settle in Ostafyevo. Karamzin, who worked here on the “History of the Russian State”. In April 1807, after the death of his father, Pyotr Andreevich Vyazemsky became the owner of the estate, under whom Ostafyevo became one of the symbols of the cultural life of Russia: Pushkin, Zhukovsky, Batyushkov, Denis Davydov, Griboyedov, Gogol, Adam Mitskevich visited here many times.

Contents of “History of the Russian State” by Karamzin

N. M. Karamzin "History of the Russian State"

In the course of his work, Karamzin found the Ipatiev Chronicle; it was from here that the historian drew many details and details, but did not clutter up the text of the narrative with them, but placed them in a separate volume of notes that have special historical significance.

In his work, Karamzin describes the peoples who inhabited the territory of modern Russia, the origins of the Slavs, their conflict with the Varangians, talks about the origin of the first princes of Rus', their reign, and describes in detail all the important events of Russian history until 1612.

The importance of N.M.’s work Karamzin

Already the first publications of “History” shocked contemporaries. They read it avidly, discovering the past of their country. Writers later used many plots for works of art. For example, Pushkin took material from “History” for his tragedy “Boris Godunov,” which he dedicated to Karamzin.

But, as always, there were critics. Basically, liberals contemporary to Karamzin objected to the statist picture of the world expressed in the work of the historian, and his belief in the effectiveness of autocracy.

Statism– this is a worldview and ideology that absolutizes the role of the state in society and promotes the maximum subordination of the interests of individuals and groups to the interests of the state; a policy of active state intervention in all spheres of public and private life.

Statism considers the state as the highest institution, standing above all other institutions, although its goal is to create real opportunities for the comprehensive development of the individual and the state.

Liberals reproached Karamzin for the fact that in his work he followed only the development of the supreme power, which gradually took the form of the autocracy of his day, but neglected the history of the Russian people themselves.

There is even an epigram attributed to Pushkin:

In his “History” elegance, simplicity

They prove to us without any bias

The need for autocracy

And the delights of the whip.

Indeed, towards the end of his life Karamzin was a staunch supporter of absolute monarchy. He did not share the point of view of the majority of thinking people on serfdom, and was not an ardent supporter of its abolition.

He died in 1826 in St. Petersburg and was buried at the Tikhvin cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

Monument to N.M. Karamzin in Ostafyevo

Among the diverse aspects of the ideological and artistic problems of the “History of the Russian State”, it should be noted that Karamzin uniquely revealed the problem of a national character. Karamzin’s very term “people” is ambiguous; it could be filled with various contents.

Thus, in the article of 1802 “On love for the fatherland and national pride” Karamzin substantiated his understanding of the people - the nation. “Glory was the cradle of the Russian people, and victory was the herald of their existence,” the historian writes here, emphasizing the originality of the national Russian character, the embodiment of which, according to the writer, is famous people and heroic events of Russian history.

Karamzin does not make social distinctions here: the Russian people appear in the unity of the national spirit, and the righteous “rulers” of the people are bearers of the best features of the national character. Such are Prince Yaroslav, Dmitry Donskoy, such is Peter the Great.

The theme of the people—the nation—occupies an important place in the ideological and artistic structure of the “History of the Russian State.” Many provisions of the article “On Love of the Fatherland and National Pride” (1802) were developed here on convincing historical material.

Decembrist N. M. Muravyov, already in the ancient Slavic tribes described by Karamzin, felt the forerunner of the Russian national character - he saw a people “great in spirit, enterprising,” containing “some kind of wonderful desire for greatness.”

The description of the era of the Tatar-Mongol invasion, the disasters that the Russian people experienced, and the courage that they showed in their quest for freedom are also imbued with a deep patriotic feeling.

The people's mind, says Karamzin, “in the greatest constraint finds some way to act, just like a river, blocked by a rock, seeks a current although it oozes in small streams underground or through the stones.” With this bold poetic image Karamzin ends the fifth volume of History, which tells about the fall of the Tatar-Mongol yoke.

But having turned to the internal, political history of Russia, Karamzin could not ignore another aspect in covering the topic of the people - the social one. A contemporary and witness to the events of the Great French Revolution, Karamzin sought to understand the causes of popular movements directed against the “legitimate rulers” and to understand the nature of the rebellions that were full of slave history in the early period.

In the noble historiography of the 18th century. There was a widespread idea of the Russian revolt as a manifestation of the “savagery” of an unenlightened people or as a result of the machinations of “rogues and swindlers.” This opinion was shared, for example, by V.N. Tatishchev.

Karamzin makes a significant step forward in understanding the social causes of popular uprisings. He shows that the forerunner of almost every rebellion is a disaster, sometimes more than one, that befalls the people: crop failure, drought, disease, but most importantly, to these natural disasters is added “oppression of the powerful.” “The governors and tiuns,” notes Karamzin, “robbed Russia like the Polovtsians.”

And the consequence of this is the author’s sad conclusion from the chronicler’s testimony: “the people hate the king, the most good-natured and merciful, for the rapacity of judges and officials.” Speaking about the formidable power of popular uprisings in the era of the Time of Troubles, Karamzin, following the chronicle terminology, sometimes calls them heavenly punishment sent by providence.

But this does not prevent him from clearly naming the real, completely earthly reasons for popular indignation - “the frantic tyranny of John’s twenty-four years, the hellish game of Boris’s lust for power, the disasters of ferocious hunger...”. Karamzin painted the history of Russia as complex, full of tragic contradictions. The idea of the moral responsibility of rulers for the fate of the state constantly emerged from the pages of the book.

That is why the traditional educational idea of monarchy as a reliable form of political structure for vast states - an idea shared by Karamzin - received new content in his History. True to his educational convictions, Karamzin wanted the “History of the Russian State” to become a great lesson to the reigning autocrats, to teach them state wisdom.

But this did not happen. Karamzin’s “history” was destined differently: it entered Russian culture in the 19th century, becoming, first of all, a fact of literature and social thought. She revealed to her contemporaries the enormous wealth of the national past, an entire artistic world in the living appearance of past centuries.

The inexhaustible variety of themes, plots, motives, and characters determined the attractive power of the “History of the Russian State” for more than one decade, including for the Decembrists, despite the fact that they could not accept the monarchical concept of Karamzin’s historical work and subjected it to sharp criticism.

The most insightful contemporaries of Karamzin, and above all Pushkin, saw in “The History of the Russian State” another, his most important innovation - an appeal to the national past as the prehistory of modern national existence, rich in instructive lessons for him.

Thus, Karamzin’s many years and multi-volume work was a significant step for its time towards the formation of civic-minded Russian socio-literary thought and the establishment of historicism as a necessary method of social self-knowledge.

This gave Belinsky every reason to say that “The History of the Russian State” “will forever remain a great monument in the history of Russian literature in general and in the history of literature of Russian history,” and to give “gratitude to the great man for giving us the means to recognize the shortcomings of his time.” , moved forward the era that followed him.”

History of Russian literature: in 4 volumes / Edited by N.I. Prutskov and others - L., 1980-1983.

In Russia, romantic historiography was represented by the works

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin(1766-1826). He came from an old noble family and was first educated at home, then in Moscow at the private boarding school of Professor Schaden. In May 1789, he undertook a trip to Western Europe, returning from which he wrote down his impressions and published “Letters of a Russian Traveler” (1797-1801).

Karamzin began to think about writing the history of Russia in 1790. According to the original plan, his life’s work was to be of a literary and patriotic nature. In 1797, he was already seriously involved in Russian history and was the first to notify the scientific world about the discovery of “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign.” In 1803, Karamzin turned to Alexander I with a request to appoint him as a historiographer with an appropriate salary and the right to receive the necessary historical sources. The request was granted. From then on, Karamzin plunged into the intense work of writing “The History of the Russian State.” By this time, he had already realized that the original plan of the work as literary and patriotic was insufficient, that he needed to give a scientific substantiation of history, that is, turn to primary sources.

As the work progressed, Karamzin’s extraordinary critical flair was revealed. In order to combine both creative plans - literary and documentary, he built his book in two tiers: the text was written in literary terms, and the notes were separated into a separate series of volumes parallel to the text. Thus, the average reader could read the book without looking at the notes, and those seriously interested in history could conveniently use the notes. Karamzin’s “Notes” represent a separate and extremely valuable work that has not lost its significance to this day, since since then some of the sources used by Karamzin have been somehow lost or not found. Before the death of the Musin-Pushkin collection in the Moscow fire of 1812, Karamzin received many valuable sources from him (Karamzin returned the Trinity Chronicle to Musin for use, as it turned out, to his death).

The main idea that guided Karamzin was monarchical: the unity of Russia, headed by a monarch supported by the nobility. All ancient Russian history before Ivan III was, according to Karamzin, a long preparatory process. The history of autocracy in Russia begins with Ivan III. In the order of his presentation, Karamzin followed in the footsteps of “Russian History” by Prince M. M. Shcherbatov. He divides the history of Russia into three periods: ancient - from Rurik, i.e. from the formation of the state, to Ivan III, middle - to Peter I and new - post-Petrine. This division of Karamzin is purely conditional, and, like all periodizations of the 18th century, comes from the history of the Russian autocracy. The fact of the calling of the Varangians in “History...” turned, in fact, into the idea of the Varangian origin of the Kyiv state, despite the contradiction of this idea with the entire nationalist orientation of Karamzin’s creation.

12 years after hard work on “History...” Karamzin published the first seven volumes. In the 20s, “History...” was published entirely in French, German, and Italian. The publication was a resounding success. Vyazemsky called Karamzin the second Kutuzov, “who saved Russia from oblivion.” “The Resurrection of the Russian People” - N. A. Zhukovsky will call “History...”.

Karamzin’s work merged two main traditions of Russian historiography: the methods of source criticism from Schletser to Tatishchev and the rationalistic philosophy of the times of Mankiev, Shafirov, Lomonosov, Shcherbatov and others.

Nikolai Mikhailovich introduced a significant number of historical monuments into scientific circulation, including new chronicle lists, for example, the Ipatiev Vault; numerous legal monuments, for example, the “Helmsman’s Book”, church charters, the Novgorod Charter of Judgment, the Code of Laws of Ivan III (Tatishchev and Miller knew only the Code of Laws of 1550), “Stoglav”. Literary monuments were also involved - “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign”, “Questions of Kirik”, etc. Following M. M. Shcherbatov, expanding the use of notes by foreigners, Karamzin attracted many new texts, starting with Plano Carpini, Rubruk, Barbaro, Contarini, Herberstein and ending with notes from foreigners about the Time of Troubles. The result of this work was extensive notes.

A real reflection of innovations in historical research remains the allocation in the general structure of “History...” of special chapters devoted to the “state of Russia” for each individual period. In these chapters, the reader went beyond purely political history and became acquainted with the internal system, economy, culture and way of life. From the beginning of the 19th century. the allocation of such chapters becomes mandatory in general works on the history of Russia.

“The History of the Russian State” certainly played a role in the development of Russian historiography. Nikolai Mikhailovich not only summed up the historical work of the 18th century, but also conveyed it to the reader. The publication of “Russian Truth” by Yaroslav the Wise, “Teachings” by Vladimir Monomakh, and finally, the discovery of “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign” aroused interest in the past of the Fatherland and stimulated the development of genres of historical prose. Fascinated by national color and antiquities, Russian writers write historical stories, “excerpts,” and journalistic articles dedicated to Russian antiquity. At the same time, history appears in the form of instructive stories that pursue educational goals.

A look at history through the prism of painting and art is a feature of Karamzin’s historical vision, reflecting his commitment to romanticism. Nikolai Mikhailovich believed that the history of Russia, rich in heroic images, is fertile material for the artist. Showing it colorfully and picturesquely is the task of the historian. The historian demanded that the national characteristics of the Russian character be reflected in art and literature, and suggested to painters themes and images that they could draw from ancient Russian literature. Nikolai Mikhailovich’s advice was readily used not only by artists, but also by many writers, poets and playwrights. His calls were especially relevant during the Patriotic War of 1812.

Karamzin outlined his historical and political program in its entirety in the “Note on Ancient and New Russia,” submitted in 1811 to Alexander I as a noble program and directed against Speransky’s reforms. This program to some extent summed up his historical studies. The main idea of N.M. Karamzin is that Russia will prosper under the scepter of the monarch. In the “Note”, he retrospectively examines all the stages of the formation of autocracy (in accordance with his “History”) and goes further, to the eras of Peter I and Catherine II. Karamzin assesses the reformism of Peter I as a turn in Russian history: “We became citizens of the world, but in some cases ceased to be citizens of Russia. It’s Peter’s fault.”

Karamzin condemns the despotism of Peter I, his cruelty, and denies the wisdom of moving the capital. He criticizes all subsequent kingdoms (“the dwarfs argued about the giant’s inheritance”). Under Catherine II, she talks about the softening of autocracy, that she cleansed it of the principle of tyranny. He has a negative attitude towards Paul I because of the humiliation of the nobles: “The Tsar took away the shame from the treasury, and the beauty from the reward.” Speaking about contemporary Russia, he notes its main problem - people steal in Russia at all times. Alexander I did not like Karamzin’s “Note,” but it became the first attempt at a political science essay in Russia.

Karamzin had a hard time with the death of Alexander I. The second shock for him was the Decembrist uprising. After spending the entire day of December 14 on the street, Nikolai Mikhailovich caught a cold and fell ill. On May 22, the historian died. He died in the midst of work, having written only twelve volumes of “History” and bringing the presentation to 1610.

Critical direction in domestic historiography of the 20-40s. XIX century

A new stage in the development of domestic historiography is associated with the emergence of a critical trend in historical science. During the controversy surrounding N. M. Karamzin’s “History of the Russian State,” the ideological foundations of his concept, understanding of the tasks and subject of historical research, attitude to the source, and interpretation of individual phenomena of Russian history were criticized. The new direction manifested itself most clearly in the works of G. Evers, N.A. Polevoy and M.T. Kachenovsky.

Evers Johann Philipp Gustav(1781-1830) - son of a Livonian farmer, studied in Germany. After graduating from the University of Göttingen, he returned to Estonia and began studying Russian history. In 1808, his first scientific work, “Preliminary Critical Studies for Russian History,” was published, written in German, like all his further works (a Russian translation was also published in 1825). The next book, “Russian History” (1816), was completed by him until the end of the 17th century. In 1810, he became a professor at the University of Dorpat, headed the department of geography, history and statistics, and lectured on Russian history and legal history. In 1818, Evers was appointed rector of the university.

Unlike Karamzin, he views the origin of the Russian state as a result of the internal life of the Eastern Slavs, who even in the pre-Varangian period had independent political associations, supreme rulers (princes), who used mercenary Vikings to strengthen their dominance. The need to unite the principalities to solve internal and external problems and the impossibility of achieving this due to discord between them in the struggle for supremacy led to the decision to transfer control to a foreigner. The summoned princes, according to Evers, had already come to the state, no matter what form it had.

This conclusion of his destroyed the traditional idea for Russian historiography that the history of Russia begins with the autocracy of Rurik. Evers also questioned the dominant assertion in historiography about the Scandinavian origin of the Varangian Rus. A study of the ethnogenesis of the peoples inhabiting the territory of Russia led him to the conclusion about the Black Sea (Khazar) origin of the Rus. He subsequently abandoned his hypothesis. His theory of tribal life played a big role in the future and was developed by K. D. Kavelin and S. M. Solovyov.

Mikhail Trofimovich Kachenovsky(1775-1842) came from a Russified Greek family. He graduated from the Kharkov Collegium and was in civil and military service. In 1790, he read Boltin’s works, which prompted him to critically develop the sources of Russian history. In 1801 he received a position as a librarian, and then as head of the personal office of Count A.K. Razumovsky. From then on, Kachenovsky's career was secured, especially since in 1807 Razumovsky was appointed trustee of Moscow University. Kachenovsky received his master's degree in philosophy in 1811 and was appointed professor at Moscow University; taught Russian history and enjoyed success with his students: the spirit of the times was changing, young people welcomed the debunking of previous authorities.

Kachenovsky's inspiration was the German historian Niebuhr, who rejected the most ancient period of Roman history as fabulous. Following in his footsteps, Kachenovsky declared the entire Kiev period fabulous, and called the chronicles, “Russian Truth”, “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign” fakes. Kachenovsky offers his own method of source analysis - at two levels of criticism: external(palaeographical, philological, diplomatic analysis of written sources in order to establish dates and authenticity) and internal(idea of the era, selection of facts).

By posing the question of the need for a critical examination of ancient Russian monuments, Kachenovsky forced not only his contemporaries, but also subsequent generations of historians to think about them, “endure anxiety, doubt, rummage through foreign and domestic chronicles and archives.” The principles he proposed for analyzing sources were generally correct, but the conclusions regarding the most ancient Russian monuments and Russian history in the 9th-14th centuries. were untenable and rejected both by their contemporaries and subsequent generations of historians.

Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy(1796-1846) entered historical science as a historian, who put forward and approved a number of new concepts and problems in it. He was the author of the 6-volume “History of the Russian People”, the 4-volume “History of Peter the Great”, “Russian History for Initial Reading”, “Review of Russian History before the Autocracy of Peter the Great”, numerous articles and reviews. Polevoy was widely known as a talented publicist, literary critic, editor and publisher of a number of magazines (including Moscow Telegraph). Polevoy came from a poor but enlightened family of an Irkutsk merchant, he was a gifted man, his encyclopedic knowledge was the result of self-education.

After the death of his father, he moved to Moscow, took up journalism, and then history. Polevoy believed that the basis for the study of history was the “philosophical method,” i.e., “scientific knowledge”: objective reproduction of the beginning, course and causes of historical phenomena. In understanding the past, Polevoy’s starting point was the idea of the unity of the historical process. Polevoy considered the law of historical life to be the continuous, progressive movement of humanity, and the source of development was the “endless struggle” of opposing principles, where the end of one struggle is the beginning of a new one. Polevoy drew attention to three factors that determine the life of mankind: natural geography, the spirit of thought and character of the people, events in the surrounding countries.

Their qualitative diversity determines the uniqueness of the historical process of each people, the manifestation of general patterns, rates and forms of life. He tried on this basis to build a scheme of world history and rethink the historical past of Russia. Polevoy's concept opened up opportunities for a broad comparative historical study of the historical process and understanding of historical experience in the context of not only European, but also Eastern history. He didn't succeed in everything. The main thing is that he was unable to write the history of the Russian people, did not go beyond general phrases about the “spirit of the people,” limiting himself to some new assessments of certain events. Ultimately, the history of the people in Polevoy’s concept remains the same history of the state, the history of autocracy.