"let's talk about this language in comparison with the Russian language. And let's ask the question: "" And we won't look at it from the point of view similar words(of which, by the way, there are not many), but from the point of view of the general logic of construction.

How are Russian and Esperanto similar? In short, they are similar in their potential for word formation, expressiveness and imagery. There is enough scientific material on this topic in Wikipedia. However, language is a delicate thing, and science alone cannot get by. So, recently I came across the article “Shibboleth” by Alexander Genis (http://www.novayagazeta.ru/arts/55784.html). Where the question of qualitative differences between the Russian language and foreign languages is raised using the example of English in a form that is pleasant to read.

Accordingly, having enjoyed this article, I thought: “Are all foreign languages inferior in comparison to Russian?” And, since from foreign languages on good level I only know Esperanto, so I started comparing it with it. And I was happy to discover that according to most of the indicators described in the article, Esperanto is not inferior to the Russian language. And in some respects it is superior :)

Which is what we'll talk about in more detail.

Start over:

“In English,” the translator sighed. - All Russians are boors.

—?! - I flushed.

“You say please,” she explained, “a thousand times less often than you should.” But this is not your fault, but ours. Or rather, our language, which in one word replaces countless Russian ways of politely expressing oneself even with a hairdryer and obscenities. To be considered polite, all you have to do is call a herring “herring,” which cannot be translated into English at all. After all, a “little herring” is a small fish, and not a universal appetizer, a glorious feast, an intimate conversation until the morning - in short, everything for which Slavists go to Moscow and sit in its kitchens.

In Esperanto you can easily say “herring”: haringeto. And this is by no means the same as haringido- small herring. Well, if you want to add even more tenderness like “a nice feast and sincere conversation,” then you can say haringetachjo(or haringachjo, harichjo and even hachjo). And any Esperantist from any corner of the world will understand you :)

If you take a cat and feed it, as happened with my Herodotus, in a “kitten”, then it will become significantly larger - and even better. “Vodyara” is stronger than vodka and closer to the heart. “Suchara” treads the line between praise and scolding. ...

Try to do without suffixes, and your speech will be like the voice of a car navigator who, like many others, does not know how to decline numerals and sound like a person. By attaching an optional tip to the word, we manage relationships with the same success with which the Japanese distribute bows, the Thais distribute smiles, the French distribute kisses, and the Americans distribute salaries. Suffixes triple the Russian vocabulary, giving each word a synonym and an antonym, and at once. Whether it’s good or bad to be a “subchik,” as I realized back when I was a pioneer, depends on who calls you that—a teacher or a girlfriend.

There are many suffixes in Esperanto. And, unlike the Russian language, they have a fixed meaning. So you can manage suffixes in Esperanto not only deftly, but also reliably (knowing that any word formation is natural and permissible, and will also be understood by any Esperantist).

Naturally, both Russian and Esperanto have prefixes that are also responsible for the nuances of speech. The combined power of prefixes and suffixes makes both Russian and Esperanto very similar in terms of life and meaning. For example: cat - cat - cat - cat = kateto - kato - katego - katacho (kategacho, katachego- depending on the meaning put into the word, more dismissive or more laudatory).

Of course, in Russian you can also say " cat", And " cat" - in Esperanto it will be the same katego. However, you have to pay for everything - and for the sake of a fixed and universally understood meaning of suffixes, Esperanto has lost a couple of synonymous suffixes. Nevertheless, the strong similarity between Russian and Esperanto in this regard is obvious.

The third point we will focus on is managing punctuation marks. There are no restrictions on their use in Esperanto. Although, without a doubt, a Russian-speaking Esperantist uses punctuation marks much more effectively than an English and so on speaker.

What I envy most are verbs: in English, almost any word can become one if it wants to. Other languages have a harder time. In Australia, for example, there is an Aboriginal language that uses only three verbs that do everything for them. We only need one, but it is indecent.

Here Esperanto is clearly ahead of Russian. In it, the same root can become a noun, an adjective, an adverb, a verb, and any other part of speech. At the same time, the norms of the language are not violated. Due to this, speech becomes definitely richer. For example, in Russian they say “there is a speech” or “our topic today is...”, whereas in Esperanto the noun temo instantly becomes an adverb theme(this adverb is not translated into Russian at all) or by a verb temi(in Russian one could say " T e wash"), expressing the necessary meaning by simply changing the suffix.

In the same way, “call on the phone” = telefoni(literally - to telephone), wield a stick = bastoni(literally - to shoot) and so on. Therefore, there is a whole layer in which the Russian language still needs to develop and develop :)

... the Russian language can do something that English rarely can: change the order of words. This precious semantic vibration is capable of turning the arrows of the text, sending it along a new path.

... I was more inspired by Bulgakov’s poetics, the key to which was the unmistakable combination of the last three words in the famous phrase from the first chapter of “The Master and Margarita”:

At that hour, when, it seemed, there was no strength to breathe, when the sun, having heated Moscow, fell in a dry fog somewhere beyond the Garden Ring, no one came under the linden trees, no one sat on the bench, the alley was empty.

The three possible options contain three genre potentials.

- “The alley was empty” means nothing, sounds neutral and requires continuation, like any story with a crime plot or hope for it.

- “The alley was empty” - you can sing it, it could become the beginning of a soul-stirring urban romance.

- “The alley was empty” is a fatal phrase. Raised to the point of ironic significance, it does not exclude ridicule of its own melodrama. A kind of provincial theater that knows its true worth, but does not hesitate to insist on it. The style is not Woland's, but Koroviev's - a petty demon whose voice the narrator rents every time he needs to quietly make fun of the heroes.

But the main thing is that all this wealth, which three English translations could not cope with, came to us like grace, without labor and freely - by inheritance.

In Esperanto, any word order is possible. In this respect it is very similar to Russian. So, the three above options for ending a novel in Esperanto would sound something like this:

- Aleo estis vaka (malplena).

- Estis vaka (malplena) aleo.

- Vaka (malplena) estis aleo.

Of course, there is no short form of the adjective in Esperanto... However, free word order is possible easily and simply. Well, the vaka / malplena option is chosen depending on what we want to emphasize - the freedom and unoccupiedness of the alley or the lack of fullness of people. If I were to translate these words, I would choose malplena.

A foreign language seems logical because you learn its grammar. Yours is a mystery because you know it without studying it. What the Russian language allows and what it does not allow is determined by the censor, who watchdog sits in the brain - understands everything, but cannot say, much less explain. ...

Language, in fact, does not seek simplicity. By imposing his inexplicable will, he endows us with national consciousness.

Esperanto grammar is very simple. It’s tens (or even hundreds) times simpler than the Russian language. Nevertheless, with its help you can achieve the same goals that the Russian language sets for itself.

And it turns out that people for whom Russian is their native language will be able to realize the full potential of Esperanto much easier than others.

And at the same time expand and improve your national identity, your system of thinking, and your way of perceiving the world. Along the way, so to speak. In passing :)

Esperanto is intended to serve as a universal international language, the second (after the native) for everyone educated person. The use of a neutral (non-ethnic) and easy-to-learn language could bring interlingual contacts to a qualitatively new level. In addition, Esperanto has great pedagogical (propaedeutic) value, that is, it significantly facilitates the subsequent study of other languages.

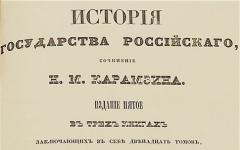

Story

In the alphabet, letters are called as follows: consonants - consonant + o, vowels - just a vowel:

- A - a

- B-bo

- C - co

Each letter corresponds to one sound (phonemic letter). Reading a letter does not depend on its position in a word (in particular, voiced consonants at the end of a word are not deafened, unstressed vowels are not reduced).

The stress in words always falls on the penultimate syllable.

The pronunciation of many letters can be assumed without special preparation (M, N, K, etc.), the pronunciation of others must be remembered:

- C ( co) is pronounced like Russian ts: centro, scene[scene], caro[tsaro] “king”.

- Ĉ ( ĉo) is pronounced like Russian h: ĉefo"chief", "head"; ĉokolado.

- G( go) is always read as G: grupo, geografio[geography].

- Ĝ ( ĝo) - affricate, pronounced like a continuous word jj. It does not have an exact correspondence in the Russian language, but it can be heard in the phrase “daughter”: due to the voiced b coming after, h is voiced and pronounced like jj. Ĝardeno[giardeno] - garden, etaĝo[ethajo] "floor".

- H ( ho) is pronounced as a dull overtone (eng. h): horizonto, sometimes as Ukrainian or Belarusian "g".

- Ĥ ( ĥo) is pronounced like the Russian x: ĥameleono, ĥirurgo, ĥolero.

- J ( jo) - like Russian th: jaguaro, jam"already".

- Ĵ ( ĵo) - Russian and: ĵargono, ĵaluzo"jealousy", ĵurnalisto.

- L ( lo) - neutral l(the wide boundaries of this phoneme allow it to be pronounced as the Russian “soft l”).

- Ŝ ( ŝo) - Russian w: ŝi- she, ŝablono.

- Ŭ ( ŭo) - short y, corresponding to English w, Belarusian ў and modern Polish ł; in Russian it is heard in the words “pause”, “howitzer”: paŭzo[pause], Eŭropo[eўropo] “Europe”. This letter is a semivowel, does not form a syllable, and is found almost exclusively in the combinations “eŭ” and “aŭ”.

Most Internet sites (including the Esperanto section of Wikipedia) automatically convert characters with xes typed in postposition (the x is not part of the Esperanto alphabet and can be considered a service character) into characters with diacritics (for example, from the combination jx it turns out ĵ ). Similar typing systems with diacritics (two keys pressed in succession to type one character) exist in keyboard layouts for other languages - for example, in the "Canadian multilingual" layout for typing French diacritics.

You can also use the Alt key and numbers (on the numeric keypad). First, write the corresponding letter (for example, C for Ĉ), then press the Alt key and type 770, and a circumflex appears above the letter. If you dial 774, a sign for ŭ will appear.

The letter can also be used as a replacement for diacritics h in post position ( this method is the "official" replacement for diacritics in cases where its use is not possible, as it is presented in the "Fundamentals of Esperanto": " Printing houses that do not have the letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ can initially use ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, u"), however, this method makes the spelling non-phonemic and makes automatic sorting and recoding difficult. With the spread of Unicode, this method (as well as others, such as diacritics in postposition - g’o, g^o and the like) is found less and less often in Esperanto texts.

Vocabulary composition

| Swadesh list for Esperanto | ||

| № | Esperanto | Russian |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | mi | I |

| 2 | ci(vi) | You |

| 3 | li | He |

| 4 | ni | We |

| 5 | vi | You |

| 6 | or | They |

| 7 | tiu ĉi | this, this, this |

| 8 | tiu | that, that, that |

| 9 | tie | here |

| 10 | tie | there |

| 11 | kiu | Who |

| 12 | kio | What |

| 13 | kie | Where |

| 14 | kiam | When |

| 15 | kiel | How |

| 16 | ne | Not |

| 17 | ĉio, ĉiuj | everything, everything |

| 18 | multaj, pluraj | many |

| 19 | kelkaj, kelke | some |

| 20 | nemultaj, nepluraj | few |

| 21 | alia | different, different |

| 22 | unu | one |

| 23 | du | two |

| 24 | tri | three |

| 25 | kvar | four |

| 26 | kvin | five |

| 27 | granda | big, great |

| 28 | longa | long, long |

| 29 | larĝa | wide |

| 30 | dika | thick |

| 31 | peza | heavy |

| 32 | malgranda | small |

| 33 | mallonga (kurta) | short, short |

| 34 | mallarĝa | narrow |

| 35 | maldika | thin |

| 36 | virino | woman |

| 37 | viro | man |

| 38 | homo | Human |

| 39 | infono | child, child |

| 40 | edzino | wife |

| 41 | edzo | husband |

| 42 | patrino | mother |

| 43 | patro | father |

| 44 | besto | beast, animal |

| 45 | fiŝo | fish |

| 46 | birdo | bird, bird |

| 47 | hundo | dog, dog |

| 48 | pediko | louse |

| 49 | serpento | snake, reptile |

| 50 | vermo | worm |

| 51 | arbo | tree |

| 52 | arbaro | forest |

| 53 | bastono | stick, rod |

| 54 | frukto | fruit, fruit |

| 55 | semo | seed, seeds |

| 56 | folio | sheet |

| 57 | radiko | root |

| 58 | ŝelo | bark |

| 59 | floro | flower |

| 60 | herbo | grass |

| 61 | ŝnuro | rope |

| 62 | haŭto | leather, hide |

| 63 | viando | meat |

| 64 | sango | blood |

| 65 | osto | bone |

| 66 | graso | fat |

| 67 | ovo | egg |

| 68 | corno | horn |

| 69 | vosto | tail |

| 70 | plumo | feather |

| 71 | haroj | hair |

| 72 | kapo | head |

| 73 | orelo | ear |

| 74 | okulo | eye, eye |

| 75 | nazo | nose |

| 76 | buŝo | mouth, lips |

| 77 | dento | tooth |

| 78 | lango | tongue) |

| 79 | ungo | nail |

| 80 | piedo | foot, leg |

| 81 | gambo | leg |

| 82 | genuo | knee |

| 83 | mano | hand, palm |

| 84 | flugilo | wing |

| 85 | ventro | belly, belly |

| 86 | tripo | entrails, intestines |

| 87 | gorĝo | throat, neck |

| 88 | dorso | back (ridge) |

| 89 | brusto | breast |

| 90 | koro | heart |

| 91 | hepato | liver |

| 92 | trinki | drink |

| 93 | manĝi | eat, eat |

| 94 | mordi | gnaw, bite |

| 95 | suĉi | suck |

| 96 | kraĉi | spit |

| 97 | vomi | vomit, vomit |

| 98 | blovi | blow |

| 99 | spiriti | breathe |

| 100 | ridi | laugh |

Most of the vocabulary consists of Romance and Germanic roots, as well as internationalisms of Latin and Greek origin. There are a small number of stems borrowed from or through Slavic (Russian and Polish) languages. Borrowed words are adapted to the phonology of Esperanto and written in the phonemic alphabet (that is, the original spelling of the source language is not preserved).

- Borrowings from French: When borrowing from French, regular sound changes occurred in most stems (for example, /sh/ became /h/). Many verbal stems of Esperanto are taken from French (iri"go", maĉi"chew", marŝi"step", kuri"to run" promeni“walk”, etc.).

- Borrowings from English: during the founding of Esperanto as an international project English language did not have its current distribution, therefore English vocabulary is rather poorly represented in the main vocabulary of Esperanto ( fajro"fire", birdo"bird", jes"yes" and some other words). Recently, however, several international Anglicisms have entered the Esperanto dictionary, such as bajto"byte" (but also "bitoko", literally "bit-eight"), blogo"blog" default"default", manaĝero"manager" etc.

- Borrowings from German: the basic vocabulary of Esperanto includes such German basics as nur"only", danko"Gratitude", ŝlosi"lock up" morgaŭ"Tomorrow", tago"day", jaro"year" etc.

- Borrowings from Slavic languages: barakti"flounder", klopodi"to bother" kartavi"burr", krom“except”, etc. See below in the section “Influence of Slavic languages”.

In general, the Esperanto lexical system manifests itself as autonomous, reluctant to borrow new bases. For new concepts, a new word is usually created from elements already existing in the language, which is facilitated by the rich possibilities of word formation. A striking illustration here can be a comparison with the Russian language:

- English site, russian website, esp. paĝaro;

- English printer, russian Printer, esp. printilo;

- English browser, russian browser, esp. retumilo, krozilo;

- English internet, russian Internet, esp. interreto.

This feature of the language allows one to minimize the number of roots and affixes required to speak Esperanto.

In spoken Esperanto there is a tendency to replace words of Latin origin with words derived from Esperanto roots on a descriptive basis (flood - altakvaĵo instead of dictionary inundo, extra - troa instead of dictionary superflua as in the proverb la tria estas troa - third wheel etc.).

In Russian, the most famous are the Esperanto-Russian and Russian-Esperanto dictionaries compiled by the famous Caucasus linguist E. A. Bokarev, and later dictionaries based on it. A large Esperanto-Russian dictionary was prepared in St. Petersburg by Boris Kondratiev and is available on the Internet. They also post [ When?] working materials of the Great Russian-Esperanto Dictionary, which is currently being worked on. There is also a project to develop and support a version of the dictionary for mobile devices.

Grammar

Verb

The Esperanto-verb system has three tenses in the indicative mood:

- past (formant -is): mi iris"I was walking" li iris"he was walking";

- the present ( -as): mi iras"I'm coming" li iras"he's coming";

- future ( -os): mi iros"I'll go, I'll go" li iros“He will go, he will go.”

In the conditional mood, the verb has only one form ( mi irus"I would go") The imperative mood is formed using a formant -u: iru! "go!" According to the same paradigm, the verb “to be” is conjugated ( esti), which can be “incorrect” even in some artificial languages (in general, the conjugation paradigm in Esperanto knows no exceptions).

Cases

There are only two cases in the case system: nominative (nominative) and accusative (accusative). The remaining relations are conveyed using a rich system of prepositions with a fixed meaning. Nominative not marked with a special ending ( vilaĝo"village"), the indicator of the accusative case is the ending -n (vilaĝon"village")

The accusative case (as in Russian) is also used to indicate direction: en vilaĝo"in the village", en vilaĝo n "to the village"; post krado"behind bars", post krado n "to jail."

Numbers

Esperanto has two numbers: singular and plural. The only thing is not marked ( infono- child), and the plural is marked using the plurality indicator -j: infanoj - children. The same is true for adjectives - beautiful - bela, beautiful - belaj. When using the accusative case with the plural at the same time, the plurality indicator is placed at the beginning: “beautiful children” - bela jn infono jn.

Genus

There is no grammatical category of gender in Esperanto. There are pronouns li - he, ŝi - she, ĝi - it (for inanimate nouns, as well as animals in cases where gender is unknown or unimportant).

Participles

Regarding the Slavic influence on the phonological level, it can be said that there is not a single phoneme in Esperanto that does not exist in Russian or Polish. The Esperanto alphabet resembles the Czech, Slovak, Croatian, Slovenian alphabets (the characters are missing q, w, x, symbols with diacritics are actively used: ĉ , ĝ , ĥ , ĵ , ŝ And ŭ ).

In the vocabulary, with the exception of words denoting purely Slavic realities ( barĉo“borscht”, etc.), out of 2612 roots presented in the “Universala Vortaro” (), only 29 could be borrowed from Russian or Polish language. Explicit Russian borrowings are banto, barakti, gladi, kartavi, krom(except), cool, nepre(certainly) prava, vosto(tail) and some others. However, Slavic influence in vocabulary is manifested in the active use of prepositions as prefixes with a change in meaning (for example, sub"under", aĉeti"buy" - subaĉeti"bribe"; aŭskulti"listen" - subaŭskulti"to eavesdrop") The doubling of stems is identical to that in Russian: plena Wed "full-full" finfine Wed "in the end". Some Slavicisms from the first years of Esperanto were leveled out over time: for example, the verb elrigardi(el-rigard-i) “look” is replaced by a new one - aspekti.

In the syntax of some prepositions and conjunctions, the Slavic influence remains, which was once even greater ( kvankam teorie… sed en la praktiko…“although in theory..., but in practice..."). According to the Slavic model, the coordination of times is carried out ( Li dir is ke li jam far is tion"He said he had already done it" Li dir is, keli est os tie"He said he would be there."

It can be said that the influence of Slavic languages (and above all Russian) on Esperanto is much stronger than is usually believed, and exceeds the influence of Romance and Germanic languages. Modern Esperanto, after the “Russian” and “French” periods, entered the so-called.

“international” period, when individual ethnic languages no longer have a serious influence on its further development.:

Literature on the issue

. He also noted that only 20 thousand people are members of various Esperantist organizations around the world.

According to the Finnish linguist J. Lindstedt, an expert on Esperantists “from birth”, for about 1000 people around the world Esperanto is their native language, about 10 thousand more people can speak it fluently, and about 100 thousand can actively use it.

Distribution by country

Most Esperanto practitioners live in the European Union, which is also where most Esperanto events take place. Outside of Europe, there is an active Esperanto movement in Brazil, Vietnam, Iran, China, USA, Japan and some other countries. There are practically no Esperantists in Arab countries and, for example, in Thailand. Since the 1990s, the number of Esperantists in Africa has been steadily increasing, especially in countries such as Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe and Togo. Hundreds of Esperantists have emerged in Nepal, the Philippines, Indonesia, Mongolia and other Asian states. The World Esperanto Association (UEA) has greatest number individual members in Brazil, Germany, France, Japan and the United States, which may be an indicator of Esperantist activity by country, although it reflects other factors (such as more life, allowing Esperantists in these countries to pay an annual fee).

Many Esperantists choose not to register with local or international organizations, making estimates of the total number of speakers difficult.

Practical use

Hundreds of new translated and original books in Esperanto are published every year. Esperanto publishing houses exist in Russia, the Czech Republic, Italy, the USA, Belgium, the Netherlands and other countries. In Russia, the publishing houses “Impeto” (Moscow) and “Sezonoj” (Kaliningrad) currently specialize in publishing literature in and about Esperanto; literature is periodically published in non-specialized publishing houses. The organ of the Russian Union of Esperantoists “Rusia Esperanto-Gazeto” (Russian Esperanto Newspaper), the monthly independent magazine “La Ondo de Esperanto” (The Esperanto Wave) and a number of less significant publications are published. Among online bookstores, the most popular is the website of the World Esperanto Organization, whose catalog in 2010 presented 6,510 different products, including 5,881 titles of book publications (not counting 1,385 second-hand books) .

The famous science fiction writer Harry Harrison himself spoke Esperanto and actively promoted it in his works. In the future world he describes, the inhabitants of the Galaxy speak mainly Esperanto.

There are also about 250 newspapers and magazines published in Esperanto; many previously published issues can be downloaded for free on a specialized website. Most publications are devoted to the activities of the Esperanto organizations that publish them (including special ones - nature lovers, railway workers, nudists, Catholics, gays, etc.). However, there are also socio-political publications (Monato, Sennaciulo, etc.), literary ones (Beletra almanako, Literatura Foiro, etc.).

There is Internet television in Esperanto. In some cases we are talking about continuous broadcasting, in others - about a series of videos that the user can select and view. The Esperanto group regularly posts new videos on YouTube. Since the 1950s, feature films and documentaries in Esperanto have appeared, as well as subtitles in Esperanto for many films in national languages. The Brazilian studio Imagu-Filmo has already released two feature films in Esperanto - “Gerda malaperis” and “La Patro”.

Several radio stations broadcast in Esperanto: China Radio International (CRI), Radio Havano Kubo, Vatican Radio, Parolu, mondo! (Brazil) and Polish Radio (since 2009 - in the form of an Internet podcast), 3ZZZ (Australia).

In Esperanto you can read the news, find out the weather around the world, get acquainted with new products in the field computer technology, choose a hotel on the Internet in Rotterdam, Rimini and other cities, learn to play poker or play various games via the Internet. International Academy Sciences in San Marino uses Esperanto as one of its working languages, and it is possible to obtain a Master's or Bachelor's degree using Esperanto. In the Polish city of Bydgoszcz, an educational institution has been operating since 1996, training specialists in the field of culture and tourism, and teaching is conducted in Esperanto.

The potential of Esperanto is also used for international business purposes, greatly facilitating communication between its participants. Examples include the Italian coffee supplier and a number of other companies. Since 1985, the International Commercial and Economic Group has been operating under the World Esperanto Organization.

With the advent of new Internet technologies such as podcasting, many Esperantists have been able to broadcast independently on the Internet. One of the most popular podcasts in Esperanto is Radio Verda (Green Radio), which has been broadcasting regularly since 1998. Another popular podcast, Radio Esperanto, is recorded in Kaliningrad (19 episodes per year, with an average of 907 listens per episode). Esperanto podcasts from other countries are popular: Varsovia Vento from Poland, La NASKa Podkasto from the USA, Radio Aktiva from Uruguay.

Many songs are created in Esperanto; there are musical groups that sing in Esperanto (for example, the Finnish rock band “Dolchamar”). Since 1990, the company Vinilkosmo has been operating, releasing music albums in Esperanto in the most different styles: from pop music to hard rock and rap. The Internet project Vikio-kantaro at the beginning of 2010 contained more than 1000 song lyrics and continued to grow. Dozens of video clips of Esperanto performers have been filmed.

There are a number of computer programs specifically written for Esperantists. Many well-known programs have versions in Esperanto - the office application OpenOffice.org, the Mozilla Firefox browser, the SeaMonkey software package and others. The most popular search engine Google also has an Esperanto version, which allows you to search for information in both Esperanto and other languages. As of February 22, 2012, Esperanto became the 64th language supported by Google Translate.

Esperantists are open to international and intercultural contacts. Many of them travel to attend conventions and festivals, where Esperantists meet old friends and make new ones. Many Esperantists have correspondents in different countries ah of peace and are often ready to provide shelter to a traveling Esperantist for several days. The German city of Herzberg (Harz) has had an official prefix to its name since 2006 - “Esperanto city”. Many signs, signs and information stands here are written in two languages - German and Esperanto. Blogs in Esperanto exist on many well-known services, especially many of them (more than 2000) on Ipernity. In the famous Internet game Second Life, there is an Esperanto community that regularly meets on the Esperanto-Lando and Verda Babilejo platforms. Esperanto writers and activists give speeches here, and linguistic courses are offered. The popularity of specialized sites helping Esperantists find: life partners, friends, jobs is growing.

Esperanto is the most successful of all artificial languages in terms of prevalence and number of users. In 2004, members of the Universala Esperanto-Asocio (World Esperanto Association, UEA) consisted of Esperantists from 114 countries, and the annual Universala Kongreso (World Congress) of Esperantists usually attracts from one and a half to five thousand participants (2209 in Florence in 2006, 1901 in Yokohama in -th, about 2000 in Bialystok in -th).

Modifications and descendants

Despite its easy grammar, some features of the Esperanto language have attracted criticism. Throughout the history of Esperanto, among its supporters there were people who wanted to change the language for the better, in their understanding, side. But since the Fundamento de Esperanto already existed by that time, it was impossible to reform Esperanto - only to create new planned languages on its basis that differed from Esperanto. Such languages are called in interlinguistics Esperantoids(esperantids). Several dozen such projects are described in the Esperanto Wikipedia: eo:Esperantidoj.

The most notable branch of descendant language projects dates back to 1907, when the Ido language was created. The creation of the language gave rise to a split in the Esperanto movement: some of the former Esperantists switched to Ido. However, most Esperantists remained faithful to their language.

However, Ido itself found itself in a similar situation in 1928 after the appearance of the “improved Ido” - the Novial language.

Less noticeable branches are the Neo, Esperantido and other languages, which are currently practically not used in live communication. Esperanto-inspired language projects continue to emerge today.

Problems and prospects of Esperanto

Historical background

Postcard with text in Russian and Esperanto, published in 1946

The position of Esperanto in society was greatly influenced by the political upheavals of the 20th century, primarily the creation, development and subsequent collapse of communist regimes in the USSR and Eastern European countries, the establishment of the Nazi regime in Germany, and the events of World War II.

The development of the Internet has greatly facilitated communication between Esperantists, simplified access to literature, music and films in this language, and contributed to the development of distance learning.

Esperanto problems

The main problems facing Esperanto are typical of most dispersed communities that do not receive financial assistance from government agencies. The relatively modest funds of Esperanto organizations, consisting mostly of donations, interest on bank deposits, as well as income from some commercial enterprises (share blocks, rental of real estate, etc.), do not allow for a wide advertising campaign to inform the public about Esperanto and its possibilities. As a result, even many Europeans do not know about the existence of this language, or rely on inaccurate information, including negative myths. In turn, the relatively small number of Esperantists contributes to the strengthening of ideas about this language as an unsuccessful project that failed.

The relative small number and dispersed residence of Esperantists determine the relatively small circulation of periodicals and books in this language. The largest circulation is the magazine Esperanto, the official organ of the World Esperanto Association (5500 copies) and the socio-political magazine Monato (1900 copies). Majority periodicals in Esperanto they are quite modestly decorated. At the same time, a number of magazines - such as “La Ondo de Esperanto”, “Beletra almanako” - are distinguished by a high level of printing performance, not inferior to the best national samples. Since the 2000s, many publications have also been distributed in the form electronic versions- cheaper, faster and more colorfully designed. Some publications are distributed only in this way, including free of charge (for example, “Mirmekobo” published in Australia).

With rare exceptions, the circulation of book publications in Esperanto is small, works of art They rarely come out with a circulation of more than 200-300 copies, and therefore their authors cannot engage professionally literary creativity(at least in Esperanto only). In addition, for the vast majority of Esperantists this is a second language, and the level of proficiency in it does not always allow them to freely perceive or create complex texts - artistic, scientific, etc.

There are examples of how works originally created in one national language were translated into another through Esperanto.

Prospects for Esperanto

The idea of introducing Esperanto as an auxiliary language of the European Union is particularly popular in the Esperanto community. Proponents of this solution believe that this will make interlingual communication in Europe more efficient and equal, while simultaneously solving the problem of European identification. Proposals for a more serious consideration of Esperanto at the European level were made by some European politicians and entire parties, in particular, representatives of the Transnational Radical Party. In addition, there are examples of the use of Esperanto in European politics (for example, the Esperanto version of Le Monde Diplomatique and the newsletter Conspectus rerum latinus during the Finnish EU Presidency). A small number of people participate in elections at the European level. Political Party"Europe - Democracy - Esperanto", which received 41 thousand votes in the 2009 European Parliament elections.

Esperanto enjoys the support of a number of influential international organizations. A special place among them is occupied by UNESCO, which adopted the so-called Montevideo resolution in 1954, which expressed support for Esperanto, the goals of which coincide with the goals of this organization, and UN member countries are called upon to introduce the teaching of Esperanto in secondary and higher educational institutions. UNESCO also adopted a resolution in support of Esperanto. In August 2009, the President of Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, in his letter expressed support for Esperanto and the hope that over time it will be accepted by the world community as a convenient means of communication that does not provide privileges to any of its participants.

As of December 18, 2012, the Esperanto section of Wikipedia contains 173,472 articles (27th place)—more than, for example, the sections in Slovak, Bulgarian or Hebrew.

Esperanto and religion

Many religions, both traditional and new, have not ignored the phenomenon of Esperanto. All major holy books have been translated into Esperanto. The Bible was translated by L. Zamenhof himself (La Sankta Biblio. Londono. ISBN 0-564-00138-4). A translation of the Koran has been published - La Nobla Korano. Kopenhago 1970. On Buddhism, edition of La Instruoj de Budho. Tokyo. 1983. ISBN 4-89237-029-0. Vatican Radio broadcasts in Esperanto, the International Catholic Esperantist Association has been active since 1910, and since 1990 the document Norme per la celebrazione della Messa in Esperanto The Holy See has officially authorized the use of Esperanto during services, the only scheduled language. On August 14, 1991, Pope John Paul II addressed more than a million young listeners in Esperanto for the first time. In 1993, he sent his apostolic blessing to the 78th World Esperanto Congress. Since 1994, the Pope, congratulating Catholics around the world on Easter and Christmas, among other languages, addresses the flock in Esperanto. His successor Benedict XVI continued this tradition.

The Baha'i Faith calls for the use of an auxiliary international language. Some Baha'is believe that Esperanto has great potential for this role. Lydia Zamenhof, the youngest daughter of the creator of Esperanto, was a follower of the Baha'i faith and translated the most important works of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá into Esperanto.

The main theses of oomoto-kyo is the slogan “Unu Dio, Unu Mondo, Unu Interlingvo” (“One God, One World, One Language of Communication”). The creator of Esperanto, Ludwig Zamenhof, is considered a saint-kami in Oomoto. The Esperanto language was introduced as an official language into Oomoto by its co-creator Onisaburo Deguchi. Won Buddhism - a new branch of Buddhism that arose in South Korea, actively uses Esperanto

Probably, at least once everyone has heard about Esperanto - a universal language destined to become global. And although the majority of people in the world still speak Chinese, this invention of the Polish doctor has its own history and prospects. Where did Esperanto come from, what kind of innovation in linguistics is it, who uses it - read on, and we will answer all these questions.

Hope for mutual understanding

Probably, since the construction of the Tower of Babel, humanity has experienced difficulties associated with misunderstanding the speech of other peoples.

The Esperanto language was developed to facilitate communication between people of different countries and cultures. It was first published in 1887 by Dr. Ludwik Lazar Zamenhof (1859–1917). He used the pseudonym "Doctor Esperanto", which means "one who hopes." This is how the name of his brainchild appeared, which he carefully developed over the years. international language Esperanto should be used as a neutral language when speaking between people who do not know each other's language.

It even has its own flag. It looks like this:

Esperanto is much easier to learn than conventional national languages that developed naturally. Its design is orderly and clear.

Lexicon

It would not be an exaggeration to say about Esperanto that it is one of the major European languages. Dr. Zamenhof took very real words for his creation as a basis. About 75% of the vocabulary comes from Latin and Romance languages (especially French), 20% comes from Germanic (German and English), and the remaining expressions are taken from Slavic languages (Russian and Polish) and Greek (mostly scientific terms). Conventional words are widely used. Therefore, a person who speaks Russian, even without preparation, will be able to read about 40% of the text in Esperanto.

The language is characterized by phonetic writing, that is, every word is pronounced exactly as it is written. No unpronounceable letters or exceptions, which makes it much easier to learn and use.

How many people speak Esperanto?

This is a very common question, but no one really knows the exact answer. The only way to reliably determine the number of people who speak Esperanto is to conduct a worldwide census, which, of course, is almost impossible.

However, Professor Sidney Culbert from the University of Washington (Seattle, USA) made the most full study on the use of this language. He has interviewed Esperanto speakers in dozens of countries around the world. From this research, Professor Culbert concluded that about two million people use it. This puts it on par with languages such as Lithuanian and Hebrew.

Sometimes the number of Esperanto speakers is exaggerated or, conversely, minimized; figures vary from 100,000 to 8 million people.

Popularity in Russia

The Esperanto language has many ardent fans. Did you know that in Russia there is an Esperanto street? Kazan became the first city of the then Russian Empire, where a club was opened dedicated to the study and dissemination of this language. It was founded by several activist intellectuals who enthusiastically accepted Dr. Zamenhof's idea and began to propagate it. Then professors and students of Kazan University opened their own small club in 1906, which could not survive for long during the turbulent years of the early twentieth century. But after Civil War the movement resumed, even a newspaper about Esperanto appeared. The language became increasingly popular as it corresponded to the Communist Party's concept of unification different nations in the name of the World Revolution. Therefore, in 1930, the street on which the Esperantist club was located received a new name - Esperanto. However, in 1947 it was renamed again in honor of the politician. At the same time, involvement in the study of this language became dangerous, and since then its popularity has fallen significantly. But the Esperantists did not give up, and in 1988 the street received its former name.

In total, there are about 1000 native speakers in Russia. On the one hand, this is not enough, but on the other, if you consider that only enthusiasts study the language in clubs, this is not such a small figure.

Letters

The alphabet is based on Latin. It contains 28 letters. Since each of them corresponds to a sound, there are also 28 of them, namely: 21 consonants, 5 vowels and 2 semivowels.

In Esperanto, the letters we are familiar with from the Latin alphabet sometimes come in pairs and are written with a “house” (an inverted checkmark on top). So Dr. Zamenhof introduced new sounds that were needed for his language.

Grammar and sentence construction

Here, too, the main principle of Esperanto is professed - simplicity and clarity. There are no genders in the language, and the order of words in a sentence is arbitrary. There are only two cases, three tenses and three There is an extensive system of prefixes and suffixes, with which you can create many new words from one root.

Flexible word order in a sentence allows different speakers to use the structures with which they are most familiar, but still speak Esperanto that is completely understandable and grammatically correct.

Practical use

New knowledge is never a bad thing, but here are some specific benefits you can get from learning Esperanto:

- This perfect second a language that can be learned quickly and easily.

- The ability to correspond with dozens of people from other countries.

- It can be used to see the world. There are lists of Esperantists who are ready to host other native speakers in their own home or apartment for free.

- International understanding. Esperanto helps break down language barriers between countries.

- The opportunity to meet people from other countries at conventions, or when foreign Esperantists come to visit you. it's the same good way meet interesting compatriots.

- International equality. When using a national language, someone must make an effort to learn an unfamiliar speech, while others only use knowledge from birth. Esperanto is a step towards each other, because both interlocutors worked hard to study it and make communication possible.

- Translations of literary masterpieces. Many works have been translated into Esperanto, some of them may not be available in native language Esperantista.

Flaws

For more than 100 years, the most widespread artificial language has acquired both fans and critics. They say about Esperanto that it is just another funny relic, like phrenology or spiritualism. Throughout its existence, it never became a world language. Moreover, humanity does not show much enthusiasm for this idea.

Critics also argue about Esperanto that it is not a simple language at all, but a difficult one to learn. Its grammar has many unspoken rules, and writing letters is difficult on a modern keyboard. Representatives from different countries are constantly trying to make their own amendments to improve it. This leads to disputes and differences in educational materials. Its euphony is also questioned.

But fans of this language argue that 100 years is too short for the whole world to speak one language, and given the number of native speakers today, Esperanto has its own future.

Esperanto - what is it? Definition, meaning, translation

Esperanto is the most popular of the artificially created languages. A universal, easy-to-learn international language was developed by the Polish Jew Lazar Zamenhof based on Latin. The idea was to create a simple and easy-to-learn language of communication between the inhabitants of the planet. The name "Esperanto" comes from the Latin Espero - "I hope".

In 1887, Lazar Zamenhof, the creator of the Esperanto language, published the first book on its study. Studying the languages of the world, he realized that in any language there are too many exceptions and complexities. The basis of Esperanto is the roots of Latin, Greek, Romano-Germanic, French and English origins.

An easy-to-remember language, the absence of exceptions and difficulties, a language that would become the next language after the native one - this is the goal that Zamenhof pursued.

Currently, Esperantists - people who speak Esperanto - number different estimates from several hundred thousand to several million.

Esperanto is in the list:

Did you find out where the word came from? Esperanto, his explanation in simple words, translation, origin and meaning.

“The inner idea of Esperanto is this: on a neutral linguistic basis, to remove the walls that separate tribes, and to teach people to see in their neighbor only a man and a brother.”

L. L. Zamenhof, 1912

This artificial language was invented by Lazarus (Ludwig) Zamenhof. He created a grammar based on European languages with a minimum of exceptions. The vocabulary is mainly taken from Romance languages, although there are also words from Germanic and other languages. New language, first appearing as a textbook in 1887, attracted public attention, and the normal process of evolution of the language began within the community that used it in different environments and created a culture associated with this language. Two decades later, the first children were born who spoke Esperanto with their parents, becoming the first native speakers. Thus, we can say that this language, created for international communication, was then creolized and today has become the language of the Esperanto-speaking diaspora.

It was created based on the vocabulary of Indo-European languages, with the goal of being easy to learn. For this reason, the grammar is agglutinative ( characteristic Turkish and Finno-Ugric languages), and at a deeper level the language is isolating (like Northern Chinese and Vietnamese). This means that the morphemes in it can be used as separate words. It has a strictly regular (without exceptions) grammar. This language also allows for the creation of a huge variety of words by combining lexical roots and about forty affixes (for example, from san-("healthy"), you can create words such as: malsana("sick"), malsanulo("a sick man"), gemalsanuloj(“sick people of both sexes”), malsanulejo(“hospitals”), sanigilo("medicine"), saniĝinto("recovered"), sanigejo(“place of treatment”), malsaneto(“little disease”), malsanego(“huge disease”), malsanegulo(“a very sick person”), sanstato (“health status”), sansento(“feeling of health”), sanlimo(“health boundaries”), malsankaŭzanto(“pathogens”), kontraŭmalsanterapio("treatment")…). The main parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) have a system of endings that allow you to recognize all parts of speech. Its systematic nature makes it easy to learn, and its flexibility in creating new words makes it one of the most productive languages, with a potentially unlimited number of words capable of expressing ever new ideas or states. For example, it is possible to write fantasy novel about invented Martians in the shape of a table and name them scoreboard("table"), tablino(“female table”), tablido(“offspring of the table”)... We can imagine a device that simplifies sex life and call it seksimpligilo(“sex simplifier”), a person who walks backwards ( inversmarŝanto, “walking backwards”), a remedy against dogmatism ( maldogmigilo, “anti-dogmatizer”), and the like.

Important features of Esperanto

The main idea of Esperanto is to promote tolerance and respect between people of different nations and cultures. Communication is a necessary part of mutual understanding, and if communication occurs in a neutral language, it can reinforce the feeling that you are “dating” on equal terms and with respect for each other.

International

Esperanto is useful for communication between representatives of different nations who do not have a common mother tongue.

Neutral

He doesn't belong to anyone to a separate people or country and therefore acts as a neutral language.

Equal

When you use Esperanto, you feel like you are on equal terms with your interlocutor from a linguistic point of view, unlike the situation when, for example, you use English to talk to someone who has spoken it since birth.

Relatively light

Due to the structure and structure of this language, it is usually much easier to master Esperanto than any foreign national language.

Alive

Esperanto develops and lives in the same way as other languages; Esperanto can express the most varied shades of human thoughts and feelings.

Equal

Everyone who learns Esperanto has a good chance of achieving a high level of proficiency in the language and then, from a linguistic point of view, communicating at the same level with others, regardless of linguistic background.

Story

Grammar

Alphabet

This is the Esperanto alphabet. Each letter is always read the same, regardless of position in the word, and words are written the same way as they are heard. Click on the example to hear the pronunciation!

- Aa ami be in love

- Bb bela beautiful

- Cc celo target

- Ĉĉ ĉokolado chocolate

- Dd doni give

- Ee egala equal

- Ff facila easy

- Gg granda big

- Ĝĝ ĝui enjoy

- Hh horo hour

- Ĥĥ ĥoro choir

- II infono child

- Jj juna young

- Ĵĵ ĵurnalo newspaper

- Kk kafo coffee

- Ll lando a country

- mm maro sea

- Nn nokto night

- Oo oro gold

- Pp paco world

- Rr rapida fast

- Ss salti jump

- Ŝŝ ŝipo ship

- Tt tago day

- Uu urban city

- Ŭŭ aŭto automobile

- Vv vivo life

- Zz zebro zebra

Nouns

All nouns in Esperanto end in -o. (Nouns are names of things and phenomena)

Plural

To get the word out plural, just add the ending -j :

Addition

In Esperanto, we indicate a direct object (that is, a word in the accusative case) in a sentence by adding -n to it. This allows us to change the order of words in a sentence the way we like, but the meaning will not change. (A direct object is something that directly experiences the action)

Adjectives

All adjectives in Esperanto end in -a. (Adjectives are used to describe nouns)

Consoles

Look! By adding mal- to the beginning of a word, we change its meaning to the opposite.

mal- is a prefix. The prefix is placed before the root to create new words. Esperanto has 10 different prefixes.

Suffixes

There are also many ways to form new words using special endings. For example, -et- reduces something.

Et- is a suffix. Suffixes must be inserted after the root to create new words. Esperanto has 31 different suffixes.

Verbs

Verbs are, of course, very important. But you will find that in Esperanto they are also very simple. (Verbs show performing an action or being in some state)

Verb forms

Verbs in the indefinite form end in -i. Verbs in the present tense end in -as, in the past - in -is, and in the future - in -os. Esperanto has neither conjugation classes nor irregular shapes verbs!

- mi est as I am

- mi est is I was

- mi est os I will

- vi est as you/you are

- vi est is you were / you were

- vi est os you will / you will

- li est as he is

- li est is he was

- li est os he will

- ŝi est as she is

- ŝi est is She was

- ŝi est os She will be

- ĝi est as it/it is

- ĝi est is it/it was

- ĝi est os it/it will be

- ni est as we are

- ni est is we were

- ni est os we will

- or est as they are

- or est is they were

- or est os they will

Adverbs

We use the ending -e to create adverbs. (Adverbs are words that describe verbs)