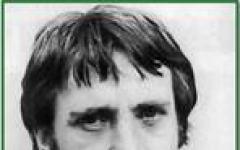

Emperor Alexander II

The “monster”, which until now lived somewhere underground, suddenly from time to time begins to stick out one of its paws. And with each appearance, he reveals greater and greater audacity and mercilessness in the execution of bloody plans and greater and greater dexterity and speed in covering his tracks. AND the mighty of the world This is why they feel that the soil is being lost under them.” (S. Stepnyak-Kravchinsky)

Terrorism [from lat. terrorem – intimidation] has a complex psychological structure and dire consequences for both the terrorists themselves and their victims. It usually manifests itself under conditions conflict situation in the threat of destruction of people or other values, including material and spiritual, if the other party does not fulfill the requirements presented to it.

Periodically, terrorism resumes, escalates, then declines, etc. Terrorism is a phenomenon social psychology and has not yet been sufficiently studied. Very often, a terrorist receives sympathy in the eyes of the people and almost the halo of a martyr. Most often, terrorism is of a political nature.

The beginning of terrorism in Russia (here we mean terrorism as a stable phenomenon that continues for a certain time) is considered to be the second half of the 19th - early 20th centuries. It is also necessary to distinguish between the concepts of “terrorism” and “terrorism”, because the first implies violence of the strong over the weak (state over the opposition), and the second implies the use of intimidation by the weak over the strong (opposition over the state).

In Russia, there are two peaks of terrorism: the second half of the 19th century - 1882. and the beginning of the 20th century - 1911.

It is believed that Karakozov's shot marked the beginning of Russian terrorism.

D. Kardovsky "Karakozov's Shot"

Shot by Karakozov

The man who shot Emperor Alexander was expelled from the list of students (of Kazan and then Moscow universities) for his participation in the riots as a nobleman from the village. Zhmakino, Serdob district, Saratov province, by Dmitry Vladimirovich Karakozov (1840-1866).

Karakozov was a member of a Moscow revolutionary circle called the “Organization,” within which there was a narrower circle of initiates under the ominous name “Hell.”

D. Karakozov

On April 4, 1866, Dmitry Karakozov shot at Emperor Alexander II: at four o'clock in the afternoon, after a usual walk in the Summer Garden, accompanied by his nephew, Duke Nicholas of Leuchtenberg, and niece, Princess Maria of Baden, he was getting into a carriage when an unknown person shot him with a pistol . The assassination attempt failed: there is a version that the shooter was pushed by the peasant O. Komissarov, this was allegedly seen by General E.I., who was present at the scene of the assassination attempt. Totleben. The Emperor immediately went from the Summer Garden to the Kazan Cathedral to give thanks to God for salvation, and Duke Nicholas and Princess Maria went to a meeting of the State Council to warn Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich about what had happened. After the meeting, he and his family went to the Kazan Cathedral a second time, where in front of the icon A thanksgiving prayer service was served to the Mother of God.

Karakozov was executed, but this incident aroused society. From all over Russia, telegrams and letters were sent expressing joy that the emperor was not injured, but some (the youngest and active part intelligentsia) elevated Karakozov to the rank of martyr. “His shot could not help but have an exciting effect on those who dreamed of struggle and a better future...” wrote a contemporary. “Let all of Russia crucify itself in devotion to the tsar and present him with addresses and icons, but Karakozov is still ours, our flesh, our blood, our brother, our friend, our comrade!” E. Breshkovskaya wrote to the correspondent.

A.I. Herzen assessed Karakozov’s action sharply negatively: “ Only among wild and decrepit peoples is history punctuated by murders“, he wrote in Kolokol two weeks after the assassination attempt.

A. Herzen

These words forever deprived him of revolutionary leadership in exile. A.A. Serno-Solovyevich replied: “ No, Mr.[sir] the founder of Russian socialism, the younger generation will not forgive you for your review of Karakozov - you cannot scrape out these lines with anything" Thus, there is a clear division of Russia into two camps: supporters of terrorism as a method of fighting autocracy and opponents of such actions.

How did it all start? N. Ishutin, a student and Karakozov’s cousin, organized a circle that aimed to “build a state on socialist ideas.” There were many such circles in Russia at that time, and almost all of them chose a not very original path - the murder of the Tsar and systematic terror. But the majority did not go beyond conversations and heated debates on this topic, and the modest and previously unnoticed D. Karakozov moved from words to deeds. His act was not clearly assessed as a crime. And few people at that time saw in his actions a symptom of the beginning of a dangerous disease of society with terrorism.

It seems that Karakozov, who shared his plans for regicide with Ishutin and other members of the circle and did not receive their approval of his intention, committed his act purely out of sporting passion and subsequent interest: what will happen after this? After the assassination attempt, Karakozov was found with a proclamation with which he addressed his “worker friends: “ The kings are the real culprits of all our troubles. When the very will came out from the king, then I saw that my truth was true. The will is this: that the smallest piece of land was cut off from the landowners' possessions, and even for that the peasant must pay a lot of money, but where can an already ruined peasant get money to buy back the land that he has been cultivating for centuries? At that time, the peasants did not believe that the tsar had so cleverly deceived them; They thought that the landowners were hiding the real will from them, and they began to refuse it and not listen to the landowners; they did not believe the intermediaries, who were also all landowners. The king heard about this and sent his generals with troops to punish the disobedient peasants, and these generals began to hang the peasants and shoot them. The peasants calmed down, accepted this will-no-will, and their lives became worse than before. I felt sad and heavy that my beloved people were dying like this, and so I decided to destroy the villain Tsar and die for my dear people myself. If my plan succeeds, I will die with the thought that by my death I brought benefit to my dear friend - the Russian peasant . But if I don’t succeed, I still believe that there will be people who will follow my path. I didn't succeed - they will succeed. For them, my death will be an example and will inspire them...”

During the investigation, Karakozov betrayed everyone from the Ishutin circle. It became known that all members of the circle had poison with them to take it in case of arrest, but no one took advantage of it.

The investigation lasted until September and suddenly stopped. This was due to the expected arrival of the bride of Tsarevich Alexander from Denmark on September 14, so as not to overshadow the celebration. Karakozov was presented as a lone terrorist, although he did not take back his testimony. At the same time, even before the start of the trial, 11 gallows were built by order of the tsar - according to the number of those suspected of the assassination attempt. On September 3, Karakozov was indicted and hanged on the same day.

After the execution of Karakozov, the family changed their surname (Vladimirovs).

The remaining defendants (34 people), mostly members of the "Hell" organization, were tried separately, but not in connection with the assassination attempt by Karakozov, but in connection with their revolutionary activity. A total of 197 people were involved in the Karakozov case; among them are Chernyshevsky’s associates, participants in the first “Land and Freedom”: A.D. Putyata, P.L. Lavrov, writers V.S. Kurochkin, G.E. Blagosvetlov, D.I. Pisarev, V.A. Zaitsev; M.A. Antonovich. No one was executed, but some were sent to hard labor. Ishutin was sentenced to hanging, a gallows was built, a crowd of people gathered on October 4, 1866 (exactly six months after the assassination attempt), and, putting a noose around the condemned man’s neck, they announced royal mercy. Ishutin went crazy and died in hard labor in 1879.

Chapel of the Savior in honor of the memory of saving the life of Alexander II after Karakozov’s shot. The square began to be called Alexandrovskaya. Postcard

On April 4, 1866, Alexander II publicly stated: “ God saved me, as long as He needs me, He will protect me. If it pleases His will to take me, it will happen».

Young I.E. Repin, together with the artist N. Murashko, was present at the execution of Karakozov; it made a grave impression on him. He left his memories about this: It seemed that he could not walk or was tetanus; his hands must have been tied. But here he was, freed, earnestly, in Russian, without haste, bowing to all the people on all four sides. This bow immediately turned this entire multi-headed field upside down, it became native and close to this alien, strange creature, which the crowd came running to look at as if it were a miracle. Perhaps only at that moment the “criminal” himself vividly felt the meaning of the moment - forgiveness forever with the world and a universal connection with it.

The executioners brought Karakozov under the gallows, placed him on a bench and put on a rope... Then the executioner, with a deft movement, knocked out the stand from under his feet.

Karakozov was already smoothly rising, swinging on the rope, his head, tied at the neck, seemed either like a doll figurine, or like a Circassian in a hood. Soon he began to bend his legs convulsively - they were wearing gray trousers. I turned to the crowd and was very surprised that all the people were in a green fog... My head was spinning, I grabbed Murashko and almost jumped off his face - it was amazingly scary with its expression of suffering; suddenly he seemed like a second Karakozov to me. God! His eyes, only his nose was shorter...”

Immediately after the execution, Repin made a pencil sketch of Karakozov.

I. Repin "D.V. Karakozov"

April 4, 1866 assassination attempt by D.V. Karakozov on Emperor Alexander II. The tsar survived, but Karakozov was sentenced to hanging.

On April 4, 1866, at four o'clock in the afternoon, Emperor Alexander II was walking in the Summer Garden, accompanied by his nephew and niece. When the walk ended and the emperor headed to the carriage that was waiting for him outside the gate, an unknown person standing in the crowd at the garden railing tried to shoot at the king. The bullet flew past because someone managed to hit the killer in the arm. The attacker was captured, and the emperor, who quickly gained control of himself, went to the Kazan Cathedral to serve a thanksgiving prayer for the happy salvation. Then he returned to Winter Palace, where frightened relatives were already waiting for him, and calmed them down.

The news of the assassination attempt on the Tsar quickly spread throughout the capital. For St. Petersburg residents, for residents of all of Russia, what happened was a real shock, because for the first time in Russian history someone dared to shoot at the king!

Dmitry Karakozov. Photo from 1866

An investigation began, and the identity of the criminal was quickly established: he turned out to be Dmitry Karakozov, a former student who was expelled from Kazan University, and then from Moscow University. In Moscow, he joined the underground group "Organization", headed by Nikolai Ishutin (according to some information, Ishutin was cousin Karakozova). This secret group claimed as its ultimate goal the introduction of socialism in Russia through revolution, and to achieve the goal, according to the Ishutinites, all means should be used, including terror. Karakozov considered the tsar to be the true culprit of all the misfortunes of Russia, and, despite the dissuasions of his comrades in secret society, came to St. Petersburg with an obsession to kill Alexander II.

Medal of Osip Komisarov, obverse.

They also established the identity of the person who prevented the killer and actually saved the tsar’s life - he turned out to be the peasant Osip Komissarov. In gratitude, Alexander II granted him the title of nobility and ordered the payment of a significant amount of money.

Medal of Osip Komisarov, reverse.

About two thousand people were under investigation in the Karakozov case, 35 of them were convicted. Most of the convicts went to hard labor and settlement; Karakozov and Ishutin were sentenced to death penalty by hanging. Karakozov's sentence was carried out on the glacis of the Peter and Paul Fortress in September 1866. Ishutin was pardoned, and this was announced to him when a noose was already placed around the condemned man’s neck. Ishutin could not recover from what happened: he went crazy in the prison of the Shlisselburg fortress.

S. Zhmakino, Saratov province - September 3, St. Petersburg) - Russian revolutionary-terrorist who committed one of the unsuccessful attempts on the life of Russian Emperor Alexander II on April 4, 1866.

Biography

He came from small landed nobility.

In the spring of 1866, on his own initiative, he went to St. Petersburg in order to assassinate the emperor. Karakozov outlined the motives for his action in a handwritten proclamation “To Friends-Workers,” in which he called on the people for revolution and the establishment of a socialist system after the regicide.

On April 4, 1866, he shot at Alexander II at the gates of the Summer Garden, but missed. He was arrested and imprisoned in the Alekseevsky Ravelin of the Peter and Paul Fortress. According to the official version, the reason for Karakozov’s mistake was that his hand was pushed away by the peasant Osip Komisarov, who was elevated to the dignity of nobility with the surname of Komissarov-Kostromsky.

In the proclamation “To Friends-Workers!”, which Karakozov distributed on the eve of the assassination attempt (one copy of it was found in the pocket of the terrorist during his arrest), the revolutionary explained the motives for his action: “I felt sad, it was hard that... my beloved people were dying, and so I decided destroy the villain king and die for his dear people. If my plan succeeds, I will die with the thought that by my death I brought benefit to my dear friend - the Russian peasant. But if I don’t succeed, I still believe that there will be people who will follow my path. I didn't succeed - they will succeed. For them, my death will be an example and will inspire them..."

The investigation into the Karakozov case was headed by Count M.N. Muravyov, who did not live two days before the verdict was pronounced. At first the terrorist refused to testify and claimed that he peasant son Alexey Petrov. During the investigation, it was established that he lived in room 65 at the Znamenskaya Hotel. A search of the room brought the police a torn letter from Ishutin, who was immediately arrested and from whom they learned Karakozov’s name. According to some data, during the investigative measures Karakozov was deprived of sleep.

During the trial in the Supreme Criminal Court (August 10 - October 1, 1866) over members of the Ishutin circle, at a meeting on August 31, chaired by Prince P. P. Gagarin, he was sentenced to death. The verdict of the Court noted that Karakozov “confessed to the attempt on the life of the “Sacred Person of the Emperor” (one of the 2 charges), explaining before the Supreme Criminal Court, when giving him a copy of the indictment, that his crime was so great that it could not be could be justified even by the painful nervous state in which he was at that time.”

Maria Alekseevna Ishutina (Karakozova) [Ishutins]Events

OK. 24 October 1840? baptism: Zhmakino, Serdobsky Uyezd, Saratov Governorate, Russian Empire

Notes

Karakozov Dmitry Vladimirovich (23.10 (4.11).1840, village of Zhmakino, Serdobsky district, Saratov province, now Penza region, - 3 (15.9.1866, St. Petersburg) - participant in the Russian revolutionary movement, was a member of a secret revolutionary society in Moscow. He graduated from the 1st Penza Men's Gymnasium in 1860, then studied at Kazan (from 1861) and Moscow (from 1864) universities. At the beginning of 1866 he belonged to the revolutionary center of the Ishutin circle, founded in Moscow in 1863 by his cousin N. A. Ishutin. In the spring of 1866 he arrived in St. Petersburg to commit an assassination attempt on the Tsar. He distributed a handwritten proclamation he wrote to “Friends-workers”, in which he called on the people for revolution. On April 4, 1866 he shot at Emperor Alexander II at the gates of the Summer Garden in St. Petersburg, but missed. He was arrested and imprisoned in the Alexander Ravelin of the Peter and Paul Fortress. According to the official version, the reason for Karakozov’s blunder was that his hand was pushed by the peasant Osip Komissarov, who was given the nobility and the surname of Komissarov-Kostromsky. The Supreme Criminal Court sentenced him to death by hanging. Executed on the Smolensk field in St. Petersburg.

Played a decisive role in the fate of the family youngest son Vladimir Ivanovich DMITRY VLADIMROVICH KARAKOZOV (1840 - 1866).

Until April 4, 1866, Dmitry's biography was extremely uneventful. Like his older brothers, Dmitry studied at the First Penza Men's Gymnasium. His mathematics teacher was Ilya Nikolaevich Ulyanov. In 1860, after graduating from high school, he entered the law faculty of Kazan University. But a year later he was expelled by order of the police and expelled from Kazan. For about a year he served as a clerk for the justice of the peace of Serdobsky district. He was admitted back to Kazan University in 1863 and dismissed from it in 1864 “for transfer to Moscow University,” from where he was expelled in the summer of 1865 for non-payment of tuition.

On April 4, 1866, at four o'clock in the afternoon, Emperor Alexander II, after a routine walk in the Summer Garden, accompanied by his nephew, Duke Nicholas of Leuchtenberg, and niece, Princess Maria of Baden, was getting into a carriage when an unknown person shot him with a pistol. At that moment, the peasant Osip Komissarov, who was standing in the crowd, hit the killer in the hand, and the bullet flew past. The criminal was detained on the spot and, by order of the emperor, taken to the III department.

The Emperor himself went straight from the Summer Garden to the Kazan Cathedral to offer thanks to God for delivering him from the danger that threatened him, and Duke Nicholas and Princess Maria hurried to the meeting State Council, to warn Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, who presided over the Council, about what had happened. When the emperor returned to the Winter Palace, all members of the State Council were already waiting for him there to offer congratulations. Having embraced the empress and the august children, the emperor and his family went a second time to the Kazan Cathedral, where a thanksgiving prayer service was served in front of the miraculous icon of the Mother of God.

The next day, at 10 o'clock in the morning, the emperor accepted the congratulations of the Senate, which came to the Winter Palace in full force, with the Minister of Justice at its head. “Thank you, gentlemen,” he told the senators, “thank you for your loyal feelings. They make me happy. I have always been confident in them. I only regret that we had to express them on such a sad event. The identity of the criminal has not yet been clarified, but it is obvious that he is who he claims to be. The most unfortunate thing is that he is Russian.”

The one who shot at the sovereign was expelled for participating in the riots from among the students of first Kazan and then Moscow universities, by a nobleman of the Saratov province Dmitry Karakozov. The discovery of the reasons that caused the crime and the identification of its accomplices was entrusted to a special investigative commission, the chairman of which was appointed Count M.N. Muravyova.

Karakozov initially hid his last name and called himself the peasant Petrov. On April 5, the chief of gendarmes, Prince Dolgorukov, wrote in a report to the Tsar: “All means will be used to reveal the truth.” It sounded ominous. The next day, Dolgorukov informed the tsar that the arrested man “was interrogated all day, without giving him rest - the priest hanged him for several hours.” A day later, the same Dolgorukov reported: “From the attached note, Your Majesty deigns to see what was done by the main investigative commission during the second half of the day. Despite this, the criminal still does not announce his real name and asks me to give him rest so that write your explanations tomorrow. Although he is really exhausted, we still need to tire him out in order to see if he will decide to be frank today.”

Kropotkin in “Notes of a Revolutionary” recounted the story of the gendarme who was guarding Karakozov in the cell that he heard in the fortress: two guards were constantly with the prisoner, changing every two hours. By order of their superiors, they did not allow Karakozov to fall asleep. As soon as he, sitting on a stool, began to doze off, the gendarmes shook him by the shoulders.

An attempt on the life of the Tsar by a nobleman seemed so unthinkable that in the first days after the arrest, the topic of Dmitry Karakozov’s mental illness was widely discussed.

The investigation established that Karakozov belonged to a Moscow secret circle led by his cousin Ishutin, which consisted mainly of young students, university students, students of the Petrovsky Agricultural Academy and students of other educational institutions; that this circle had the ultimate goal of carrying out a violent coup d'état; that the means to achieve this was to bring him closer to the people, teach them to read and write, establish workshops, artels and other similar associations to spread socialist teachings among the common people. It was also established that members of the Moscow circle had connections with like-minded people in St. Petersburg, with exiled Poles and with Russian immigrants abroad.

The investigation revealed, moreover, the unsatisfactory state of most educational institutions, higher and secondary, the unreliability of teachers, the spirit of rebellion and self-will of students and even high school students, who were carried away by the teachings of unbelief and materialism, on the one hand, and the most extreme socialism, on the other, openly preached in magazines of the so-called advanced direction.

The sessions of the Supreme Court, to which Karakozov was committed, took place in the same Peter and Paul Fortress, where the Decembrists and Petrashevites were tried. Alexander II wished that the process be completed as soon as possible. The court included persons whose merciless cruelty was known in advance. The chairman of the court was Prince Gagarin.

His not at all dispassionate judicial mood spilled out at the very beginning of the trial, when he told the court secretary that he would address Karakozov as “you,” since “such a villain has no opportunity to say “you.” However, the secretary managed to convince him to address the defendant to "you".

During the trial itself, the king’s desire to speed up the end of the process was brought to the attention of the chairman. “If Karakozov’s execution is not carried out before August 26, then the sovereign emperor does not want it to happen between August 26 (coronation day) and August 30 (his name day day).” This was the verdict. He was taken out. Its pronouncement was preceded by a private meeting of the court members at the chairman’s apartment, where it was decided to execute Karakozov alone. Court member Panin agreed with this very reluctantly, saying that “of course, it is better to execute two than one, and three is better than two.”

Karakozov, completely broken by the investigation and the trial, testified and submitted a request for pardon. The Minister of Justice, who was also the prosecutor in the trial, reported it to the tsar, which he later recounted: “What an angelic expression was on the sovereign’s face when he said that he had long ago forgiven him, as a Christian, but, as a sovereign, he does not consider himself entitled to forgive.” ". So, hypocritically, with pompous phrases, the tsar, an unlimited monarch, limited himself in the right to get rid of the condemned man from the gallows!..

On September 2, the chairman of the court summoned Karakozov from the ravelin to the building where the trial was taking place. Karakozov entered with such a bright face that, apparently, he was expecting a pardon, but he heard about the confirmation of the sentence, and all the light disappeared from his face, it darkened and took on a stern and gloomy expression. The convict had to wait a whole day for execution.

In addition to Karakozov, the Supreme Criminal Court tried 35 other defendants in his case, divided into two groups. 11 people were included in the first group along with Karakozov, and 25 in the second. In addition, the government dealt with some of those arrested in the same case without trial, in an administrative manner. The accused were accused of some form of involvement in the assassination attempt on Alexander II and participation in an organization that aimed at a coup d'etat and the establishment of new social principles. The majority of the circle members did not go beyond attempts to organize artels and production partnerships, or beyond intentions to conduct propaganda with the help of libraries and schools. The indictments primarily charged members of a society called "Hell", in which the assassination of the Tsar as a means of coup was the subject of discussion.

Most of the accused during the investigation and in court, after being sentenced to hard labor and settlement, submitted requests for pardon. Ishutin, who was sentenced to hanging, submitted a request for pardon after the execution of Karakozov and Ishutin. He was pardoned after the entire ceremony was performed on him public execution up to dressing in a shroud and putting a noose around the neck. This cost him the loss of his mental health. The age of the convicts ranged from 19 to 26 years.

On September 3, 1866, at 7 o'clock in the morning, Dmitry Karakozov was taken from the Peter and Paul Fortress to the Smolensk field. Thousands of people, despite the early hour, gathered here. Everyone was waiting for execution...

The court secretary Ya. G. Esipovich, who was present at the execution of the sentence, wrote in his memoirs:

“A wide road was left between the vast masses of people, along which we reached the square formed from the troops. Here we got out of the carriage and entered the square. A scaffold was erected in the center of the square, a gallows was placed to the side of it, opposite the gallows a low wooden platform for the Minister of Justice with his retinue. Everything was painted black. We stood on this platform.

Soon a shameful chariot drove up to the scaffold, on which Karakozov sat with his back to the horses, chained to a high seat. His face was blue and deathly. Filled with horror and silent despair, he looked at the scaffold, then began to look with his eyes for something else, his gaze stopped for a moment on the gallows, and suddenly his head convulsively and as if involuntarily turned away from this terrible object.

And the morning began so clear, bright, sunny!”

And so the executioners calmly, without haste, unchained Karakozov. Then, taking him by the arms, they lifted him to the high scaffold, to the pillory. The crowd of thousands fell silent and, fixing their gaze on the scaffold, waited for what would happen next.

Minister of Justice D.N. Zamyatin turned to Esipovich and said loudly:

"Mr. Secretary of the Supreme Criminal Court, announce the court's verdict publicly!"

Esipovich, with difficulty overcoming his excitement, climbed the steps of the scaffold, leaned on the railing and began to read:

"By order of His Imperial Majesty..."

After these words, the drums beat, the army stood guard, and everyone took off their hats. When the drums died down,” Esipovich continued, “I read the verdict word by word and then returned again to the platform where the Minister of Justice stood with his retinue.

When I came down from the scaffold, Archpriest Palisadov, Karakozov’s confessor, ascended it. In vestments and with a cross in his hands, he approached the condemned man, told him his last parting words, let him kiss the cross and left.

The executioners began to put a shroud on him, which completely covered his head, but they were unable to do this properly, because they did not put their hands into his sleeves. The police chief, sitting on horseback near the scaffold, said this. They again took off the shroud and put it on again so that their hands could be tied back with long sleeves. This, of course, also added one extra bitter minute to the condemned man, for when the shroud was taken off him, shouldn’t the thought of pardon have flashed through him? And again they put on the shroud again, now for the last time."

A witness to the execution of Karakozov was the aspiring artist Ilya Repin, who left memories entitled “The Execution of Karakozov”, published in the collection of memoirs “Distant Close”.

It was already a completely white day when in the distance a black cart without springs swayed with a bench on which Karakozov was sitting. Only the width of a cart, the road was guarded by the police, and in this space it was clearly visible how the “criminal” swayed from side to side on the cobblestone pavement. Attached to the plank bench wall, it looked like a motionless mannequin. He sat with his back to the horse, without changing anything in his deadened position... Here he was approaching, now he was passing us. Everyone is walking and close past us. It was possible to clearly see the face and the entire position of the body. Petrified, he held on, turning his head to the left. The color of his face was characteristic feature solitary confinement - which had not seen air or light for a long time, it was pale yellow, with a grayish tint; His hair, light blond, naturally inclined to curl, had a grayish-ashy tinge, had not been washed for a long time and was matted haphazardly under a prisoner-style cap, slightly pulled down in front. The long, protruding nose looked like the nose of a dead man, and the eyes, directed in one direction, were huge. gray eyes, without any shine, also seemed to be on the other side of life: not a single living thought or living feeling could be noticed in them; only tightly compressed thin lips spoke of the remnant of frozen energy of someone who had decided and endured his fate to the end. The overall impression from him was especially terrible. Of course, he bore on himself, in addition to this whole appearance, the death sentence decided upon him, which (it was on everyone’s faces) would be carried out now.

The gendarmes and some other servants, taking off his black prisoner's cap, began to push him to the middle of the scaffold. He seemed unable to walk or was tetanus; his hands must have been tied. But here he was, freed, earnestly, in Russian, without haste, bowing to all the people on all four sides. This bow immediately turned this entire multi-headed field upside down, it became native and close to this alien, strange creature, which the crowd came running to look at as if it were a miracle. Perhaps only at that moment the “criminal” himself vividly felt the meaning of the moment - farewell to the world forever and the universal connection with it.

And forgive us, for Christ’s sake,” someone muttered muffledly, almost to himself.

“Mother, the queen of heaven,” the woman intoned.

Of course, God will judge,” said my neighbor, a merchant in appearance, with a tremor of tears in his voice.

Ooh! Fathers!.. - the woman howled.

The crowd began to hum dully, and even some shouts of whoops were heard... But at that time the drums began beating loudly. Again for a long time they could not put on the “criminal” a continuous cap of unbleached canvas, from the pointed crown to slightly below the knees. In this case, Karakozov could no longer stand on his feet. The gendarmes and attendants, almost on their hands, led him along a narrow platform up to a stool, above which hung a noose on a block from the black verb of the gallows. The already mobile executioner stood on the stool: he reached for the noose and lowered the rope under the sharp chin of the victim. Another performer standing at the post quickly tightened the noose around his neck, and at the same moment, jumping from the stool, the executioner deftly knocked the stand out from under Karakozov’s feet. Karakozov was already smoothly rising, swinging on the rope, his head, tied at the neck, seemed either like a doll figurine, or like a Circassian in a hood. Soon he began to bend his legs convulsively - they were wearing gray trousers. I turned to the crowd and was very surprised that all the people were in a green fog... My head began to spin, I grabbed Murashko and almost jumped away from his face - it was amazingly scary with its expression of suffering; suddenly he seemed like a second Karakozov to me. God! His eyes, only his nose was shorter.

Russian Emperor Alexander II the Liberator (1818-1881) is considered one of the most outstanding monarchs Great Empire. It was under him that it was canceled serfdom(1861), zemstvo, city, judicial, military, and educational reforms were carried out. According to the idea of the sovereign and his entourage, all this was supposed to bring the country to a new round of economic development.

However, not everything worked out as expected. Many innovations extremely aggravated the internal political situation in the huge state. The most acute discontent arose as a result of the peasant reform. At its core, it was enslaving and provoked mass unrest. In 1861 alone there were more than a thousand of them. Peasant protests were suppressed extremely brutally.

The situation was aggravated by the economic crisis that lasted from the early 60s to the mid-80s of the 19th century. The rise in corruption was also notable. Massive abuses occurred in the railway industry. During construction railways private companies stole most of the money, and officials from the Ministry of Finance shared with them. Corruption also flourished in the army. Contracts for supplying troops were given for bribes, and instead of quality goods, military personnel received low-quality products.

In foreign policy the sovereign was guided by Germany. He sympathized with her in every possible way and did a lot to create a militaristic power under the nose of Russia. In his love for the Germans, the Tsar went so far as to order that the Kaiser's officers be rewarded St. George's crosses. All this did not add to the popularity of the autocrat. The country has seen a steady increase in popular discontent, both internal and foreign policy state, and the attempts on the life of Alexander II were the result of weak rule and royal lack of will.

Revolutionary movement

If state power suffers from shortcomings, then many oppositionists appear among educated and energetic people. In 1869, the Society of People's Retribution was formed. One of its leaders was Sergei Nechaev (1847-1882), a terrorist of the 19th century. A terrible person, capable of murder, blackmail, and extortion.

In 1861, the secret revolutionary organization “Land and Freedom” was formed. It was a union of like-minded people, numbering at least 3 thousand people. The organizers were Herzen, Chernyshevsky, Obruchev. In 1879, "Land and Freedom" split into the terrorist organization "People's Will" and the populist wing, called the "Black Redistribution".

Pyotr Zaichnevsky (1842-1896) created his own circle. He distributed prohibited literature among young people and called for the overthrow of the monarchy. Fortunately, he didn’t kill anyone, but he was a revolutionary and a promoter of socialism to the core. Nikolai Ishutin (1840-1879) also created revolutionary circles. He argued that the end justifies any means. He died in a hard labor prison before reaching the age of 40. Pyotr Tkachev (1844-1886) should also be mentioned. He preached terrorism, not seeing other methods of fighting the government.

There were also many other circles and unions. All of them were actively involved in anti-government agitation. In 1873-1874, thousands of intellectuals went to the villages to propagate revolutionary ideas among the peasants. This action was called "going to the people."

Beginning in 1878, a wave of terrorism swept across Russia. And the beginning of this lawlessness was laid by Vera Zasulich (1849-1919). She seriously wounded the mayor of St. Petersburg, Fyodor Trepov (1812-1889). After this, the terrorists shot at gendarmerie officers, prosecutors, and governors. But their most desired goal was the emperor Russian Empire Alexander II.

Assassination attempts on Alexander II

Assassination of Karakozov

The first attempt on the life of God's anointed took place on April 4, 1866. Terrorist Dmitry Karakozov (1840-1866) raised his hand against the autocrat. He was Nikolai Ishutin's cousin and ardently advocated individual terror. He sincerely believed that by killing the Tsar, he would inspire the people to a socialist revolution.

The young man, on his own initiative, arrived in St. Petersburg in the spring of 1866, and on April 4, he waited for the emperor at the entrance to the Summer Garden and shot at him. However, the life of the autocrat was saved by the small businessman Osip Komissarov (1838-1892). He stood in the crowd of onlookers and stared at the emperor getting into the carriage. Terrorist Karakozov was nearby a few seconds before the shot. Komissarov saw the revolver in the stranger’s hand and hit it. The bullet went up, and Komissarov, for his courageous act, became a hereditary nobleman and received an estate in the Poltava province.

Dmitry Karakozov was arrested at the crime scene. From August 10 to October 1 of the same year passed trial chaired by Actual Privy Councilor Pavel Gagarin (1789-1872). The terrorist was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on September 3, 1866 in St. Petersburg. The criminal was hanged on the Smolensk field in public. At the time of his death, Karakozov was 25 years old.

Berezovsky's assassination attempt

The second attempt on the life of the Russian Tsar took place on June 6, 1867 (the date is indicated according to Gregorian calendar, but since the assassination attempt took place in France, it is quite correct). This time, Anton Berezovsky (1847-1916), a Pole by origin, raised his hand against God’s anointed one. He took part in the Polish uprising of 1863-1864. After the defeat of the rebels he went abroad. Since 1865 he lived permanently in Paris. In 1867, the World Exhibition opened in the capital of France. It demonstrated the latest technical achievements. The exhibition was of great international importance, and the Russian Emperor came to it.

Having learned about this, Berezovsky decided to kill the sovereign. He naively believed that in this way he could make Poland a free state. On June 5 he bought a revolver, and on June 6 he shot at the autocrat in the Bois de Boulogne. He was traveling in a carriage with his 2 sons and the French emperor. But the terrorist did not have the appropriate shooting skills. The fired bullet hit the horse of one of the riders, who was galloping next to the crowned heads.

Berezovsky was immediately captured, put on trial and sentenced to life in hard labor. They sent the criminal to New Caledonia - this is the southwestern part Pacific Ocean. In 1906, the terrorist was amnestied. But he did not return to Europe and died in a foreign land at the age of 69.

The third attempt occurred on April 2, 1879 in the capital of the empire, St. Petersburg. Alexander Solovyov (1846-1879) committed the crime. He was a member of the revolutionary organization "Land and Freedom". On the morning of April 2, the attacker met the emperor on the Moika embankment while he was taking his usual morning walk.

The Emperor was walking unaccompanied, and the terrorist approached him at a distance of no more than 5 meters. A shot was fired, but the bullet flew past without hitting the autocrat. Alexander II ran, the criminal chased after him and fired 2 more shots, but again missed. At this time, gendarmerie captain Koch arrived. He hit the attacker on the back with a saber. But the blow landed flat, and the blade bent.

Solovyov almost fell, but stayed on his feet and threw a shot at the emperor’s back for the 4th time, but missed again. Then the terrorist rushed towards Palace Square to escape. He was interrupted by people rushing to the sound of gunfire. The criminal shot at the running people for the 5th time, without causing harm to anyone. After that he was captured.

On May 25, 1879, a trial was held and the attacker was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on May 28 of the same year on the Smolensk field. Several tens of thousands of people attended the execution. At the time of his death, Alexander Solovyov was 32 years old. After his execution, members of the executive committee gathered" People's Will"and made a decision to kill the Russian emperor at any cost.

Explosion of the Suite train

The next attempt on Alexander II's life occurred on November 19, 1879. The Emperor was returning from Crimea. There were 2 trains in total. One is royal, and the second with his retinue is retinue. For safety reasons, the suite train moved first, and the royal train went at intervals of 30 minutes.

But in Kharkov, a malfunction was discovered in the locomotive of the Svitsky train. Therefore, the train containing the sovereign went ahead. The terrorists knew about the route, but did not know about the breakdown of the locomotive. They missed the royal train, and the next train, which contained an escort, was blown up. The 4th car overturned due to the explosion great strength, but, fortunately, no one was killed.

Assassination of Khalturin

Another unsuccessful attempt was made by Stepan Khalturin (1856-1882). He worked as a carpenter and was closely associated with the Narodnaya Volya. In September 1879, the palace department hired him to do carpentry work in the royal palace. They settled there in the semi-basement. A young carpenter brought explosives to the Winter Palace, and on February 5, 1880, he caused a powerful explosion.

It exploded on the 1st floor, and the emperor was having lunch on the 3rd floor. That day he was late, and at the time of the tragedy he was not in the dining room. Absolutely innocent people from the guard, numbering 11, died. More than 50 people were injured. The terrorist fled. He was detained on March 18, 1882 in Odessa after the murder of prosecutor Strelnikov. He was hanged on March 22 of the same year at the age of 25.

The last fatal assassination attempt on Alexander II took place on March 1, 1881 in St. Petersburg on the embankment of the Catherine Canal. It was accomplished by Narodnaya Volya members Nikolai Rysakov (1861-1881) and Ignatius Grinevitsky (1856-1881). The main organizer was Andrei Zhelyabov (1851-1881). The immediate leader of the terrorist attack was Sofya Perovskaya (1853-1881). Her accomplices were Nikolai Kibalchich (1853-1881), Timofey Mikhailov (1859-1881), Gesya Gelfman (1855-1882) and her husband Nikolai Sablin (1850-1881).

On that ill-fated day, the emperor was riding in a carriage from the Mikhailovsky Palace after breakfast with Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich and Grand Duchess Ekaterina Mikhailovna. The carriage was accompanied by 6 mounted Cossacks, two sleighs with guards, and another Cossack sat next to the coachman.

Rysakov appeared on the embankment. He wrapped the bomb in a white scarf and walked straight towards the carriage. One of the Cossacks galloped towards him, but did not have time to do anything. The terrorist threw a bomb. There was a strong explosion. The carriage sank to one side, and Rysakov tried to escape, but was detained by security.

In the general confusion, the emperor got out of the carriage. The bodies of dead people lay all around. Not far from the site of the explosion, a 14-year-old teenager was dying in agony. Alexander II approached the terrorist and asked his name and rank. He said that he was a Glazov tradesman. People ran up to the sovereign and began to ask if everything was okay with him. The emperor replied: “Thank God, I was not hurt.” At these words, Rysakov bared his teeth angrily and said: “Is there still glory to God?”

Not far from the scene of the tragedy, Ignatius Grinevitsky stood at the iron grating with the second bomb. Nobody paid attention to him. The Emperor, meanwhile, moved away from Rysakov and, apparently in shock, wandered along the embankment, accompanied by the police chief, who asked to return to the carriage. In the distance was Perovskaya. When the Tsar caught up with Grinevitsky, she waved her white handkerchief, and the terrorist threw a second bomb. This explosion turned out to be fatal for the autocrat. The terrorist himself was also mortally wounded by the exploding bomb.

The explosion disfigured the emperor's entire body. He was put into a sleigh and taken to the palace. Soon the sovereign died. Before his death, he regained consciousness for a short time and managed to take communion. On March 4, the body was transferred to the home of the temple of the imperial family - the Court Cathedral. On March 7, the deceased was solemnly transferred to the tomb of the Russian emperors - the Peter and Paul Cathedral. The funeral service took place on March 15. It was headed by Metropolitan Isidore, the leading member of the Holy Synod.

As for the terrorists, the investigation took the detained Rysakov into a tough turn, and he very quickly betrayed his accomplices. He named a safe house located on Telezhnaya Street. The police arrived there, and Sablin, who was there, shot himself. His wife Gelfman was arrested. Already on March 3, the remaining participants in the attempt were arrested. Who managed to escape punishment was Vera Figner (1852-1942). This woman is a legend. She stood at the origins of terrorism and managed to live 89 years.

The trial of the First Marchers

The organizers and perpetrator of the assassination attempt were tried and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on April 3, 1881. The execution took place on the Semyonovsky parade ground (now Pionerskaya Square) in St. Petersburg. They hanged Perovskaya, Zhelyabov, Mikhailov, Kibalchich and Rysakov. Standing on the scaffold, the Narodnaya Volya members said goodbye to each other, but did not want to say goodbye to Rysakov, since they considered him a traitor. Those executed were subsequently named March 1st, since the attempt was committed on March 1.

Thus ended the assassination attempts on Alexander II. But at that time, no one could even imagine that this was only the beginning of a series of bloody events that would result in a civil fratricidal war at the beginning of the 20th century..