Many of Akhmatova's poems are an appeal to tragic destinies Russia. The First World War in Akhmatova’s poetry marked the beginning of difficult trials for Russia. Akhmatova’s poetic voice becomes the voice of people’s sorrow and at the same time hope. In 1915, the poetess wrote “Prayer”:

Give me the bitter years of illness, Choking, insomnia, fever, Take away both the child and the friend, And the mysterious gift of song - So I pray at Your liturgy After so many languid days, So that the cloud over dark Russia Becomes a cloud in the glory of the rays.The revolution of 1917 was perceived by Akhmatova as a disaster. The new era that came after the revolution was felt by Akhmatova as a tragic time of loss and destruction. But revolution for Akhmatova is also retribution, retribution for a past sinful life. And let her lyrical heroine did not do evil, but she feels her involvement in the common guilt, and therefore is ready to share the fate of her homeland and her people, she refuses to emigrate. See the poem "I had a voice..." (1917):

I had a voice. He called comfortingly, He said: “Come here, Leave your deaf and sinful land, Leave Russia forever. I will wash the blood from your hands, I will take the black shame out of my heart, I will cover the pain of defeats and insults with a new name.” But indifferently and calmly I closed my ears with my hands, so that the sorrowful spirit would not be defiled by this unworthy speech. 1917“There was a voice for me,” it is said as if it were a question of divine revelation. But this is obviously both an inner voice, reflecting the heroine’s struggle with herself, and the imaginary voice of a friend who left his homeland. The answer sounds conscious and clear: “But indifferently and calmly...” “Calmly” here means only the appearance of indifference and calmness; in fact, it is a sign of the extraordinary self-control of a lonely but courageous woman.

During the Great Patriotic War Akhmatova was evacuated to Tashkent and returned to Leningrad in 1944. During the war years, the theme of the Motherland becomes the leading one in Akhmatova’s lyrics. In the poem "Courage", written in February 1942, the fate of the native land is associated with fate native language, a native word that serves as a symbolic embodiment of the spiritual principle of Russia:

We know what is now on the scales and what is happening now. The hour of courage has struck on our watch, And courage will not leave us. It’s not scary to lie dead under bullets, It’s not bitter to be left homeless, - And we will save you, Russian speech, Great Russian word. We will carry you free and clean, And we will give you to your grandchildren, and we will save you from captivity Forever! 1942During the war, universal human values came to the fore: life, home, family, homeland. Many considered it impossible to return to the pre-war horrors of totalitarianism. So the idea of "Courage" is not limited to patriotism. Spiritual freedom forever, expressed in faith in the freedom of Russian speech - this is for the sake of which the people perform their feat.

The final chord of Akhmatova’s theme of the homeland is the poem “Native Land” (1961):

And there are no more tearless people in the world, more arrogant and simpler than us. 1922 We don’t carry it on our chests in treasured amulet, We don’t write poems about her to the point of sobbing, She doesn’t awaken our bitter dreams, It doesn’t seem like a promised paradise. We don’t make her in our souls an object of purchase and sale, sick, in poverty, silent on her, we don’t even remember about her. Yes, for us it’s dirt on our galoshes, Yes, for us it’s a crunch on our teeth. And we grind, and knead, and crumble that unmixed dust. But we lie down in it and become it, That’s why we call it so freely - ours. 1961The epigraph is based on lines from his own poem written in 1922. The poem is light in tone, despite the foreboding near death. In fact, Akhmatova emphasizes the loyalty and inviolability of her human and creative position. The word "earth" is polysemantic and meaningful. This is the soil (“dirt on galoshes”), and the homeland, and its symbol, and the theme of creativity, and the primal matter with which the human body is united after death. The collision of different meanings of the word along with the use of a variety of lexical and semantic layers ("overshoes", "sick"; "promised", "silent") creates the impression of exceptional breadth and freedom.

In Akhmatova’s lyrics, the motif of an orphaned mother appears, which reaches its peak in “Requiem” as Christian motive eternal maternal fate - from era to era to sacrifice sons to the world:

Magdalena struggled and sobbed, the beloved student turned to stone, and where the Mother stood silently, no one dared to look.And here again Akhmatova’s personal is combined with a national tragedy and the eternal, universal. This is the uniqueness of Akhmatova’s poetry: she felt the pain of her era as her own pain. Akhmatova became the voice of her time; she was not close to power, but she also did not stigmatize her country. She wisely, simply and mournfully shared her fate. Requiem became a monument to a terrible era.

Anna Akhmatova during the Great Patriotic War - page No. 1/1

Anna Akhmatova during the Great Patriotic War.

Great Patriotic War Soviet people, which he fought for four long years with German fascism, defending both the independence of his homeland and the existence of the entire civilized world, was a new stage in the development of Soviet literature. Over the course of more than twenty years of previous development, she achieved, as we know, serious artistic results. Her contribution to the artistic knowledge of the world lay primarily in the fact that she showed the birth of a person in a new society. Over the course of these two decades, Soviet literature gradually included, along with new names, various artists of the older generation. Anna Akhmatova was one of them. Like some other writers, she experienced a complex ideological evolution in the 20s and 30s.

The war found Akhmatova in Leningrad. Her fate at this time continued to be difficult: her son, who had been arrested for the second time, was in prison, and efforts to free him led nowhere. A certain hope for making life easier arose before 1940, when she was allowed to collect and publish a book of selected works. But Akhmatova, naturally, could not include in it any of the poems that directly related to the painful events of those years. Meanwhile, the creative upsurge continued to be very high, and, according to Akhmatova, the poems came in a continuous stream, “stepping on each other’s heels, hurrying and out of breath...”.

There appeared and initially existed unformed passages called “strange” by Akhmatova, in which individual features and fragments of a past era arose - right up to 1913, but sometimes the memory of the poem went even further - to the Russia of Dostoevsky and Nekrasov. The year 1940 was particularly intense and unusual in this regard. Fragments of past eras, scraps of memories, faces of long-dead people persistently knocked on the consciousness, mixing with later impressions and strangely echoing the tragic events of the 30s. However, the poem “The Way of the Whole Earth,” seemingly thoroughly lyrical and deeply tragic in its meaning, also includes colorful fragments of past eras, bizarrely adjacent to the modernity of the pre-war decade. In the second chapter of this poem, the years of youth and almost childhood appear, splashes of the Black Sea waves are heard, but at the same time, the reader’s gaze appears... the trenches of the First World War, and in the penultimate chapter the voices of people appear, saying latest news about Tsushima, about “Varyag” and “Korean”, that is, about the Russian-Japanese war...

It was not for nothing that Akhmatova wrote that it was precisely from 1940 - from the time of the poem “The Path of All the Earth” and the work on “Requiem” - that she began to look at the entire past community of events as if from some kind of high tower.

During the war years, along with journalistic poems (“Oath”, “Courage”, etc.), Akhmatova wrote several works more close-up, in which she comprehends the entire past historical bulk of the revolutionary time, again returns in memory to the era of 1913, reconsiders it, judges it, decisively discards many things that were previously dear and close, searches for origins and consequences. This is not a departure into history, but the approach of history to the difficult and difficult day of the war, a unique historical and philosophical understanding of the grandiose war that unfolded before her eyes, which was not characteristic of her alone.

During the war years, readers knew mainly “The Oath” and “Courage” - they were published in newspapers at one time and attracted general attention as a rare example of newspaper journalism from such a chamber poet, as A. Akhmatova was in the perception of the majority of the pre-war years . But in addition to these truly wonderful journalistic works, full of patriotic inspiration and energy, she wrote many other, no longer journalistic, but also in many ways new things for her, such as the poetic cycle “The Moon at its Zenith” (1942-1944), “On Smolensk Cemetery” (1942), “Three Autumns” (1943), “Where on four high paws...”

(1943), “Prehistory” (1945) and especially fragments from “Poem without a Hero”, begun back in 1940, but mainly still voiced by the years of war.

The military lyrics of A. Akhmatova require deep understanding, because, in addition to its undoubted aesthetic and human value, it is also of interest as an important detail of the literary life of that time, the searches and discoveries of that time.

Critics wrote that the intimate and personal theme during the war years gave way to patriotic excitement and anxiety for the fate of humanity. True, if we adhere to greater precision, then we should say that the expansion of internal horizons in Akhmatova’s poetry began with her, as we have just seen in the example of “Requiem” and many works of the 30s, significantly before years war. But in general terms, this observation is correct, and it should be noted that a change in creative tone, and partly even method, was characteristic during the war years not only of A. Akhmatova, but also of other artists of similar and dissimilar fates, who, being previously far from civil words and broad historical categories unusual for thinking, also changed both internally and in verse.

Of course, all these changes, no matter how unexpected they may seem, were not so sudden. In each case one can find a long preliminary accumulation of new qualities; the war only accelerated this complex, contradictory and slow process, reducing it to the level of an instant patriotic reaction. We have already seen that in Akhmatova’s work the time of such accumulation was the last pre-war years, especially 4935-1940, when the range of her lyrics, also unexpectedly for many, expanded to the possibility of mastering political and journalistic areas: the cycle of poems “In the fortieth year”, etc. .

This appeal to political lyrics, as well as to works of civil and philosophical meaning (“The Path of All the Earth,” “Requiem,” “Shards,” etc.) on the very eve of the Great Patriotic War turned out to be extremely important for her further poetic development. It is this civic and aesthetic experience and the conscious goal of putting one’s verse to work hard day people and helped Akhmatova meet the war with warlike and militant verse. It is known that the Great Patriotic War did not take poets by surprise: in the very first days of the battles, most of them left for the fronts as soldiers, officers, and war correspondents; those who could not directly participate in the military affairs of the people became participants in the intense working life of the people of those years. Olga Berggolts recalls Akhmatova from the very beginning of the Leningrad siege:

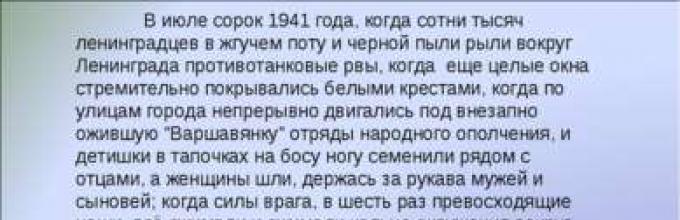

“On a lined sheet of paper, torn from an office book, written under the dictation of Anna Andreevna Akhmatova, and then corrected by her hand, a speech on the radio - to the city and on the air - during the hardest days of the storming of Leningrad and the attack on Moscow.

As I remember her near the ancient forged gates against the backdrop of the cast-iron fence of the Fountain House, the former Sheremetyev Palace, with a face closed in severity and anger, with a gas mask over her shoulder, she was on duty like an ordinary soldier air defense. She sewed sandbags that lined shelter trenches in the garden of the same Fountain House under the maple tree she sang in “Poem Without a Hero.” At the same time, she wrote poetry, fiery, laconic Akhmatova-like quatrains:

Enemy Banner

It will melt like smoke

The truth is behind us

And we will win!”

“I went to see Akhmatova,” Pavel recalls meeting with her in August 1941. Luknitsky.-She was lying sick. She greeted me very warmly; She was in a good mood and said with visible pleasure that she had been invited to speak on the radio. She is a patriot, and the knowledge that she is now in soul with everyone, apparently, greatly encourages her.”

By the way, the quatrain cited by Olga Berggolts shows well that even the rough language of the poster, so seemingly far from the traditional manner of Akhmatova, even he, when the need arose, suddenly appeared and sounded in her verse, which did not want to be aside neither from common misfortune, nor from common courage. Akhmatova found the blockade, she saw the first cruel blows inflicted on the city she had praised so many times. Already in July the famous “Oath” appears:

And the one who today says goodbye to her beloved, -

Let her transform her pain into strength.

We swear to the children, we swear to the graves,

That no one will force us to submit!

The Muse of Leningrad wore in those difficult days military uniform. One must think that she also appeared to Akhmatova then in a stern, courageous guise. But, unlike the years of the First World War, when, we remember, Akhmatova experienced a feeling of hopeless, all-eclipsing grief that knew no way out or clearing, now there is firmness and courage, calm and confidence in her voice: “The enemy’s banner will melt away like smoke.” . P. Luknitsky correctly felt that the reason for this courage and calmness is in the feeling of unity with the life of the people, in the consciousness that “she is now in soul with everyone.” Here is the watershed that runs between early Akhmatova, the period of the First World War, and the author of “The Oath” and “Courage”.

She did not want to leave Leningrad and, being evacuated and then living for three years in Tashkent, did not stop thinking and writing about the abandoned city. Knowing about the torment of besieged Leningrad only from stories, letters and newspapers, the poetess felt, however, obliged to mourn the great victims of her beloved city. Some of her works of this time, in their high tragedy, echo the poems of Olga Berggolts and other Leningraders who remained in the ring of the blockade. The word “mourner,” with which Bergholz was then so often and in vain reproached, first appeared in relation to Leningrad precisely from Akhmatova. She attached, of course, high poetic meaning to this word. Her poetic requiems included words of rage, anger and defiance:

And you, my friends of the last call,

In order to mourn you, my life has been spared.

Do not freeze over your memory like a weeping willow,

And shout all your names to the whole world!

What names are there!

After all, it doesn’t matter - you are with us!..

Everyone on your knees, everyone!

Crimson light poured out!

And Leningraders again walk through the smoke in rows -

The living are with the dead: for glory there are no dead.

A you, my friends of the last call!..

Olga Berggolts felt the same way about her poetic duty. Addressing the City, she wrote:

Isn't it you yourself

Biblically threatening winter

he called me to the brotherly trenches

and, all ossified and tearless,

ordered his children to mourn?

Your way

Of course, Akhmatova does not have direct descriptions of the war; she did not see it. In this regard, with all the moments of sometimes surprising coincidences (intonation and figurative) that are sometimes found between poems written in the ring and on the mainland, they, of course, still cannot be placed close to each other. Poems by O. Berggolts, N. Tikhonov, V. Shefner, V. Sayanov. Sun. Rozhdestvensky and other poets who were surrounded by the blockade actively participated in the military and labor feats of Leningraders; they, in addition, were saturated with such details and touches of life that people who were far away could not have. But Akhmatova’s works in this case are dear because they expressed feelings of compassion, love and sorrow that were then coming to Leningrad from all over countries. In her poetic messages, along with pathos permeated with bitterness and melancholy, there was a lot of simple human affection.

Such, for example, are her poems to Leningrad children, in which there are many maternal unshed tears and compassionate tenderness:

Knock with your fist and I will open it.

I always opened up to you.

I'm now behind a high mountain,

Beyond the desert, beyond the wind and heat,

But I will never betray you...

I didn’t hear your moan,

You didn't ask me for bread.

Bring me a maple branch

Or just blades of green grass,

Like you brought last spring.

Bring me a handful of clean ones

Our Neva icy water,

And from your golden head

I will wash away the bloody traces.

Knock with your fist - I'll open...

A feeling of undivided community with the City:

Our separation is imaginary:

I'm indistinguishable from you

My shadow is on your walls -

in her poetry there was equal community with the country, with the people.

It is characteristic that her war lyrics are dominated by a broad and happy “we”. “We will preserve you, Russian speech”, “courage will not leave us”, “our homeland has given us shelter” - she has a lot of such lines, testifying to the novelty of Akhmatova’s worldview and the triumph of the people’s principle. Numerous blood threads of kinship with the country, previously loudly declaring themselves only at certain turning points in the biography (“I had a voice. He called comfortably...”, 1917; “Petrograd”, 1919; “That city, familiar to me from childhood.. .”, 1929; “Requiem”, 1935-1940), became forever the main, most dear, determining both the life and sound of poetry.

The homeland turned out to be not only St. Petersburg, not only Tsarskoe Selo, but also the entire huge country, spread across the boundless and saving Asian expanses. “It is strong, my Asian home,” she wrote in one of the poems, recalling that by blood (“Tatar grandmother”) she is connected with Asia and therefore has the right, no less than Blok, to speak with the West as on her behalf: -

We know what's on the scales now

And what is happening now.

The hour of courage has struck on our watch.

And courage will not leave us.

It's not scary to lie dead under bullets,

It's not bitter to be homeless, -

And we will save you, Russian speech,

Great Russian word.

We will carry you free and clean,

We will give it to our grandchildren and save us from captivity

Courage

From this point of view, the cycle “Moon at its zenith” (1942-1944), reflecting life in evacuation, seems no less important than poems devoted directly to the military theme. Essentially this is a small poem, built on the principle of Blok’s poetic cycles. The individual poems that make up the work are not interconnected by any external plot connection; they are united by a common mood and the integrity of a single lyrical and philosophical thought.

“The Moon at its Zenith” is one of Akhmatova’s most picturesque works. The musicality (“subtlety”) of the composition, based on the alternation of motifs and images that arise outside the external framework of the poem, is noticeably preserved here from the previous features of poetics. Semi-fairy-tale, mysterious Asia, its night darkness, the bitter smoke of its hearths, its motley tales - this is the initial motive of this cycle, which immediately takes us from military worries to the world of “eastern peace”. Of course, this peace is illusory. As soon as it appears in the reader’s imagination, it is immediately, within itself, interrupted by a luminous vision of Leningrad - its protective light, obtained at the cost of blood, having overcome space, entered the distant “Asian” night, recalling the security granted at the price of the blockade. The dual motive Leningrad-Asia gives birth to the third, the most powerful and triumphant - the melody of national unity:

Who dares to tell me that here

Am I in a foreign land?!.

Moon at zenith

All the same choirs of stars and waters,

The vaults of the sky are still black,

The wind still carries the grains,

And the mother sings the same song.

It is strong, my Asian home,

And no need to worry...

I'll come again. Flowers, fence,

Be full, clean reservoir.

Moon at zenith

And in the center of the cycle, like its living pulsating heart, the main motif, the motive of great hope, beats, grows and diverges in circles:

I meet the third spring in the distance

From Leningrad.

Third? And it seems to me that she

Will be the last...

Moon at zenith

The expanded range of lyrics, a largely different vision of the world, unusually spread out both in time and space, the time of high civil experience brought by the war - all this could not help but introduce new ideas and searches for appropriate artistic forms into her work. The years of war in Anna Akhmatova's work are marked by a tendency towards the epic.

This circumstance says a lot. After all, she made her first attempts to create works of an epic appearance back in her Acmeistic period, in 1915.

These were the already mentioned “Epic Motifs” and, to a certain extent, the poem “Near the Sea”. Of course, in relation to these two works, the very term “epic” must be taken almost metaphorically, at least extremely conditionally; Akhmatova appears in them primarily as a lyricist.

But if we talk about the poem “By the Sea itself,” then the very length of the theme, stretching into the distance of human destiny, and even the very sound of this poem, reproducing the melody of an epic song, all involuntarily hinted at the kinship of its works of an epic nature.

As for “Epic Motifs,” without putting a classification meaning into this name, Anna Akhmatova had in mind mainly the breadth of narrative intonation that she chose for these large poetic fragments, which absorb the diverse details of a beautifully diverse life. But there is a big fundamental difference between these two works, which hint at Akhmatova’s potential, and some of her works during the war years. An incomparably greater similarity can be seen between them and “Requiem”. In “Requiem” we already feel the epic basis steadily expanding, and at times even directly emerging. Akhmatova’s lyrical voice in this work turned out to be akin to a large and unfamiliar circle of people, whose suffering she sings out and poetically enhances as if it were her own.

If we recall some of Akhmatova’s other already mentioned works of the pre-war years, we can say that her first real access to the broad themes and problems of the era was realized precisely in the late 30s. However, a truly new understanding of his time and serious changes in the content of the verse arose in the poet during the Great Patriotic War.

Akhmatova’s memorable verse often leads to the origins of the modern era, which on the burning day of war so brilliantly withstood the severe test of strength and maturity.

The first sign of the beginning of the search was, apparently, the poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery.” Written in 1942, it might seem unrelated to the war that was then raging. However, this is not so: like many other artists of the war years, Akhmatova does not so much go into the past as strive to bring it closer to the present day in order to establish socio-temporal causes and consequences.

It is significant that the persistent need to comprehend the Time, the Century, the War in the entire breadth of historical perspectives, right up to that foggy distance of centuries, where the stable outlines of Russian statehood are already lost from sight, giving way to a poetic feeling of national history - this need, growing out of the desire to make sure in the strength and inviolability of our today's existence, was characteristic of a wide variety of artists.

History hastily approached its warring contemporary in the epic miniatures of A. Surkov of 1941, and in the lyrical confessions of K. Simonov, and in the documented, but always poetically inspired creations of D. Kedrin, and in the historical variations of S. Gorodetsky... Moreover , it is difficult to name a poet, prose writer and playwright of those years who, in one form or another, sometimes indirect and unexpected, would not have expressed this natural desire to feel the powerful and saving thickness of the national-historical fertile soil.

The tragic day of war, fraught with unexpected fluctuations, urgently demanded that artistic consciousness be included in the solid supporting frame of history.

Artists of various talents and dispositions approached the solution of this difficult task in different ways, in our own way.

Olga Berggolts, for example, in her siege poems, accurately and reliably depicting the torment of besieged Leningrad, continually directed her memory to those revolutionary coordinates Soviet history, with which she was connected biographically: to October and her own Komsomol youth, which helped her artistically comprehend Leningrad life as an expression of high human existence, as a triumph of the great ideals of the Revolution.

Margarita Aliger and Pavel Antokolsky, in their poems about Soviet youth, also could not ignore the vastness of time that shaped the Soviet character - in one form or another they turned to recreating the biography of the country.

Vladimir Lugovskoy began to solve this same problem most widely during the war years. In his “Mid-Century” all the main stages of the history of the Soviet state were reproduced. Refusing to depict any objectified hero, the poet himself acted as a narrator on behalf of History. This was not only an “artistic device” that helped the poet use his superior lyrical talent, like A. Akhmatova’s, but also something more: an ordinary participant in events speaking on behalf of history - this is, after all, an expression of the ideals of the new time.

Everyone who wrote about Akhmatova, including L. Ozerov, K. Chukovsky, A. Tvardovsky and others, noted the historicism of both narration and poetic thinking, which was so unusual for her previous work. “In the early Akhmatova,” L. Ozerov rightly wrote, “we will hardly find works in which time would be described and generalized, its time would be highlighted.” characteristic features. In later cycles, historicism is defined as a way of understanding the world and human existence, a way that dictates a special manner of writing.” L. Ozerov and K. Chukovsky see the first serious victories of historicism in A. Akhmatova in her “Prehistory”.

One can, of course, argue about the accuracy of this date, especially if we recall her poems from 1935-1940, but there is no doubt that the first obvious achievements in the field of historical understanding of reality date back to the years of the Great Patriotic War. After all, she then not only wrote several significant poems of the corresponding plan, but also continued the work begun back in 1940, on “Poem without a Hero,” in which lyrically colored historicism became the most characteristic feature of the entire narrative. No wonder it was said in one of her poems from those years:

As if all the primordial memory is in consciousness

Flowed like red-hot lava,

As if I were my own sobs

She drank from other people's palms.

These are your lynx eyes, Asia...

Among the many different poems she wrote during the war years, sometimes lyrically tender, sometimes imbued with insomnia and darkness, there are some that are, as it were, companions to the “Poem without a Hero” that was created at the same time. In them, Akhmatova goes down the roads of memory - to her youth, to 1913, remembers, weighs, judges, compares. The great concept of Time powerfully enters her lyrics and colors them in unique tones. She never resurrected an era just like that, for the sake of reconstruction, although her amazing memory for details, for details, for the very air of past time and everyday life would have allowed her to create a plastic and dense depiction of everyday life. But here is the poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery”:

And everyone I found on earth

You, centuries of past decrepit sowing,

This is where it all ended: dinners at Donon's,

Intrigues and ranks, ballet, current account....

On a dilapidated plinth there is a noble crown

And the rusty angel sheds dry tears.

The East still lay as an unknown space

And rumbled in the distance like a formidable enemy camp,

And from the West there was a Victorian swagger,

Confetti flew and the cancan howled...

It is difficult to imagine in Akhmatova’s previous work not only the unique imagery of this poem, but also its intonation. Detached from the past, ironic and dry, this intonation most of all, perhaps, speaks of the dramatic changes that have occurred in the poetess’s worldview. In essence, in this small poem she seems to sum up the past era. ~ The main thing here is the feeling of the great divide that lies between two centuries: the past and the present, the complete and final exhaustion of this past, unresurrected, sunk into the grave abyss forever and irrevocably. Akhmatova sees herself standing on this shore, on the shore of life, not death.

One of the favorite and constant philosophical ideas, which invariably arose in her mind when she touched on the past, is the idea of the irreversibility of Time. The poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery” talks about the ephemerality of an imaginary human existence, limited by an empty, fleeting minute. “...Dinners at Do-non’s, intrigues and ranks, ballet, current account” - in this one phrase both the content and the essence of the imaginary, and not the real, are captured human life. This “life,” Akhmatova argues, is essentially empty and insignificant, equal to death. Dry tears from the eyes of a forgotten rusty angel - this is the result of such an existence and the reward for it. Genuine Time - synonymous with Life - appears for her, as a rule, when a sense of the history of the country, the history of the people enters the poem. In the poems of the Tashkent period, either Russian or Central Asian landscapes appeared, replacing and flowing into each other, imbued with a feeling of bottomlessness going deep into the depths. national life, its steadfastness, strength, eternity.

In the poem “Under Kolomna” (“Poppies in red hats are walking”), an ancient ringing bell tower sunk into the ground rises up and the ancient smell of mint stretches over a stuffy summer field, spread freely and widely in Russian style:

Everything is made of logs, planks, bent...

A full minute is spent

On the hourglass...

During the war years, which threatened the very existence of the state and the people, not only Akhmatova, but also many other poets had a persistent desire to peer into the eternal and beautiful face of the Motherland. Simonovsky’s widely known and beloved motif of three birch trees in those years, from which the great concept of “Motherland” originates, sounded in one form or another among all the artists of the country. Very often this motive was voiced historically: it was born from the then heightened sense of the continuity of times, the continuity of generations and centuries. Fascism intended, having stopped the clock of history, to arrogantly turn its hands in the opposite direction - into the cave lair of the beast, into the dark and bloody life of the ancient Germans, rulers of devastated spaces. Soviet artists, turning to the past, saw in it the origins of humanity’s irreversible movement towards progress, towards improvement, towards civilization. During the Great Patriotic War, much was written historical novels and stories, plays and poems. Artists tended to turn to the great historical periods associated with liberation wars, with the activities of large historical figures. History has repeatedly appeared in propaganda journalism - in A. Tolstoy, K. Fedin, L. Leonov... In poetry, Dmitry Kedrin was an unrivaled master of historical pictorial lyricism.

Akhmatova’s originality lay in the fact that she was able to poetically convey the very presence of the living spirit of the times, history in people’s lives today. In this regard, for example, her poem “Under Kolomna” unexpectedly but organically echoes the initial poems of Vl. Lugovsky from “Mid-Century”, especially with “The Tale of Grandfather’s Fur Coat”. After all, Vl. Lugovskaya in this tale, like Akhmatova, also strives to convey the male spirit of Russia, the very music of its eternal landscape. In “The Tale of Grandfather’s Fur Coat,” he goes to the very origins of national existence, to that landscape-historical womb that was not yet called, perhaps, by the name of Rus', but from which Rus' was born, emerged and began to be. Justifying his plan with childish atavistic intuition, he unfolds semi-legendary pictures of the Ancient Motherland with great expressive power.

Akhmatova does not retreat into a fairy tale, into a legend, into a legend, but she is constantly characterized by the desire to capture the stable, lasting and enduring: in the landscape, in history, in nationality. That's why she writes that

The ancient sun from a gray cloud

A long gaze is fixed and tender.

Near Kolomna

A in another poem he utters words that are quite strange, at first impression:

I haven't been here for seven hundred years,

But nothing has changed...

God's mercy continues to flow

From undisputed heights...

All the same choirs of stars and waters,

The vaults of the sky are still black,

And just like the wind carries the grains,

And my mother sings the same song...

I haven't been here for seven hundred years...

In general, the theme of memory is one of the most important in her lyrics of the war years:

And in memory, as if in a patterned arrangement:

The gray smile of all-knowing lips,

Grave turban noble folds

And the royal dwarf - pomegranate bush.

And in memory, as if in a patterned arrangement...

And rummaging through your black memory, you will find...

Three poems

I. remembers Rogachevskoe highway

The robber whistle of young Blok...

Three poems

By the way, Blok with his patriotic concepts expressed in “Scythians” turned out to be resurrected by Akhmatova during the war years. Blok’s theme of the saving “Asian” expanses and the mighty Russian Sknfism, rooted in the thousand-year-old firmament of the earth, sounded strong and expressive to her. In addition, she also brought into her a personal attitude towards the somewhat expansive Asia-Russia Bloc, because, by the will of the war, having been thrown into distant Tashkent, she recognized this region from the inside - not only symbolically, but also from its landscape and everyday side .

If Blok’s “Scythians” are instrumented in the tones of high oratorical eloquence, which does not imply any mundane, let alone everyday realities, then Akhmatova, following Blok in his main poetic thought, is always concrete, material and objective. Asia (more specifically, Central Asia) for a time, of necessity, became her home, and for this reason she brought into her poems something that the author of “Scythians” did not have - a homely feeling of this great flowering land, which became a refuge and a barrier in the most difficult times. a time of the most difficult national trial. In her lines there appear the “mangalochny courtyard”, and blossoming peaches, and the smoke of violets, and the solemnly beautiful “biblical daffodils”:

I meet the third spring in the distance

From Leningrad.

Third? And it seems to me that she

It will be the last one.

But I will never forget

Until the hour of death,

How the sound of water pleased me

In the shade of a tree...

The peach blossomed, and the violets smoke

Everything is more fragrant.

Who dares to tell me what is here.

Am I in a foreign land?!

I meet the third spring in the distance...

Earth ancient culture, Central Asia repeatedly evoked images of legendary Eastern thinkers, lovers and prophets in her mind. Philosophical lyrics were widely included in her work during the evacuation period for the first time. It seems that its emergence is connected precisely with the feeling of the closeness of the great philosophical and poetic culture that permeates both the earth and the air of this peculiar region. The starry sky of Asia, the whisper of its irrigation ditches, black-haired mothers with babies in their arms, the huge silver moon, so different from the one in St. Petersburg, the transparent and reverently protected reservoirs on which the life and well-being of people, animals and plants depend - everything inspired the idea of eternity and incorruptibility of human existence and thought:

Our sacred craft

Has been around for thousands of years...

With him, even without light, the world is bright.

But no poet has yet said,

That there is no wisdom and no old age,

Or maybe there is no death.

Our sacred craft...

These lines could only have been born under the Asian sky.

Akhmatova’s favorite thought, which formed the focus of her later philosophical lyrics, the idea of the immortality of indestructible human life, first arose and became stronger among her precisely during the war years, when the very foundations of rational human existence were threatened with destruction.

A characteristic feature of Akhmatova’s lyrics during the war years is the combination of two poetic scales, surprising in its unexpected naturalness: on the one hand, acute attentiveness to the smallest manifestations of the everyday life surrounding the poet, colorful little things, expressive details, strokes, sounding details, and on the other hand, huge sky above your head and ancient land under your feet, a feeling of eternity rustling with its breath right next to your cheeks and eyes. Akhmatova is unusually colorful and musical in her Tashkent poems.

From mother of pearl and agate,

From smoky glass,

So unexpectedly sloping

And so solemnly she swam, -

It's like Moonlight Sonata

She immediately crossed our path.

Moon phenomenon

However, along with works directly inspired by Asia, its beauty and solemn majesty, the philosophical nature of its nights and the sultry sparkle of scorching afternoons, next to this charm of life, which gave birth in its lyrics to an unexpected feeling of the fullness of being, continued all the time, gave no rest and tirelessly moved forward. the work of seeking poetic memory. The harsh and bloody day of war, which claimed thousands of young lives, stood relentlessly before her eyes and consciousness. The great, solemn silence of safe Asia was ensured by the inescapable torment of the fighting people: only a selfish person could forget about the deadly war that never ceased to thunder. The inviolability of the eternal foundations of life, which was a life-giving and lasting ferment in Akhmatov’s verse, could not strengthen and preserve the human heart, unique in its individual existence, but poetry should be addressed to it first of all. Subsequently, many years after the war, Akhmatova will say:

Our time on earth is fleeting

And the appointed circle is small,

And he is unchanging and eternal -

The poet's unknown friend.

Reader

People, warring contemporaries - this is what should be the poet’s main concern. This feeling of duty and responsibility to an unknown friend-reader, to the people can be expressed in different ways: during the war years we know the combat propaganda journalism that raised the fighters to attack, we know “Dugout” by Alexei Surkov and “Kill him!” Konstantin Simonov. Hundreds of thousands of Leningraders who did not survive the first winter of the siege took with them to their graves the unique sisterly voice of Olga Berggolts...

Art, including poetry of the Great Patriotic War, was diverse. Akhmatova introduced her special lyrical stream into this poetic flow. Her poetic requiems washed with tears, dedicated to Leningrad, were one of the expressions of national compassion that went to the Leningraders through the fiery ring of the blockade during the endless siege years; her philosophical thoughts about the multi-layered cultural firmament resting under the feet of the warring people objectively expressed the general confidence in the indestructibility and indestructibility of life, culture, nationality , which the newly-minted Western Huns so arrogantly aimed at.

And finally, another and, perhaps, the most important aspect of Akhmatova’s creativity of those years is the attempt to synthetically comprehend the entire past panorama of time, attempts to find and show the origins of the great brilliant victories of the Soviet people in their battle with fascism. Fragmentarily, but persistently, Akhmatova resurrects individual pages of the past, trying to find in them not just characteristic details preserved by memory and documents, but the main nerve nodes of previous historical experience, its starting stations, which she herself had once been to, without realizing the pre-prepared along distant historical routes.

Throughout the years of the war, although sometimes with long interruptions, she worked on the “Poem without a Hero,” which is essentially a Poem of Memory. Many poems of that time internally accompanied the poem, invisibly pushed it, sharpened and formed its extensive and not immediately clear plan. The already mentioned poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery,” for example, contained, of course, one of the most important melodies of “Poem without a Hero”: the melody of counting back time, revaluing values, exposing the tawdry of an outwardly respectable and prosperous existence. His general sarcastic, contemptuous tone also noticeably echoes some of the inspiredly evil, almost satirical pages of the poem.

The historicism of thinking could not help but affect some of the new features of the lyrical narrative that Akhmatova appeared during the war years. Along with works where her lyrical, subjective-associative style remains the same, she appears in poems of an unusual narrative appearance, as if prosaic in their coloring and in the nature of the realistic signs of the everyday side of the era interspersed in them. This especially applies to “Prehistory”. It seemed to complete the cycle of development that was outlined and begun by the poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery.” “Prehistory” has a significant epigraph: “Now I live without noise” - from Pushkin’s “House in Kolomna”.

Akhmatova, thus, finally and sharply separates herself from the previous era - not so much, of course, biographically, as psychologically. This is the 80s of the 19th century. They are recreated by the poetess with the help of those general historical and general cultural sources that are firmly connected in our minds with the era of Dostoevsky and the young Chekhov, the victorious spirit of Russian capitalism and with the last giant figures of Russian culture, mainly with Tolstoy. Akhmatova also recalls Nekrasov and Saltykov in “Prehistory”:

And my counterparts live -

Nekrasov and Saltykov...

Both have a Memorial plaque.

Oh, how scary it would be

They should see these boards!..

Background

L. Tolstoy appears in “Prehistory” as the author of “Anna Karenina”. This is no coincidence: the era of the 70-80s is the Karenin era. But let's take a closer look at the poem itself:

Russia of Dostoevsky. Moon

Almost a quarter is hidden by the bell tower.

The taverns are selling, the cabs are flying,

Five-story buildings are growing

In Gorokhovaya, near Znamenya, near Smolny.

There are dance classes everywhere, signs change,

And next to it: “Henriette”, “Basil”, “Andre”

And magnificent coffins: “Shumilov Sr.”...

Background

As we see, this is not the “snowy” Petersburg traditional for Akhmatova and Blok, but something completely different. The author's view of the era captured in the appearance of the city is harsh and accurate. As in the poem “At the Smolensk Cemetery,” a satirical note is clearly heard here, but without any outwardly satirical shift in proportions: everything is real, accurate, almost documentary, and in its figurative system it is almost prosaic. In appearance, this is a page of prose, an excerpt from a novel, outlining the usual plot exposition for a novel action.

The mention of the name of Dostoevsky, Gorokhovaya Street and the bell tower vividly evokes the familiar corner of Dostoevsky’s St. Petersburg - Sennaya Square, not far from which, near Sadovaya, lived a student who decided to kill an old money-lender. The succinctness of this small piece is absolutely amazing. The spirit of Dostoevsky, restless over the ghostly Petersburg, gives the whole picture a certain generalized symbolic meaning that fits into the usual literary tradition; but the growing five-story buildings, money changer signs, dance classes and, as the crown of everything, “magnificent coffins: “Shumilov Sr.” - “all this materially vulgar nature of someone’s nourishing and animal life alien and hostile to the City. How new and unusual such an image is for the work of Anna Akhmatova!

The rustling of skirts, checkered plaids,

Walnut frames on the mirrors,

Amazed by the Karenn beauty,

And in the narrow corridors that wallpaper,

Which we admired in childhood,

And the same ivy on the chairs...

Everything is different, hastily, somehow...

Fathers and grandfathers are incomprehensible. Earth

Pawned. And in Baden - roulette...

Background

Korney Chukovsky, partly a witness and eyewitness of the end of that era, says about this poem:

“I saw the end of this era and can testify that its very flavor, its very smell are conveyed in “Prehistory” with the greatest accuracy.

I remember this props from the seventies well. The plush on the chairs was a pungent green color, or even worse, crimson. And each chair was edged with thick fringe, as if specially created for collecting dust. And the same fringe on the curtains. Mirrors were indeed then in brown walnut frames, dotted with ornate carvings of roses or butterflies. “The rustling of skirts,” which is so often mentioned in novels and stories of that time, ceased only in the twentieth century, and then, in accordance with fashion, it was a stable feature of all secular and semi-secular living rooms. To make it completely clear to us what the exact date of all these disparate images was, Akhmatova mentions Anna Karenina, whose entire tragic life is tightly connected with the second half of the seventies.

1 slide

2 slide

In July 1941, when hundreds of thousands of Leningraders in burning sweat and black dust dug anti-tank ditches around Leningrad, when whole windows were rapidly covered with white crosses, when detachments were continuously moving along the city streets under the suddenly revived "Varshavyanka" people's militia, and children in slippers on bare feet minced next to their fathers, and women walked holding the sleeves of their husbands and sons; when the enemy forces, six times superior to ours, were tightening and tightening the encirclement ring around Leningrad, and daily reports brought news of Russian cities abandoned after bloody battles - these days, four large lines appeared in Leningradskaya Pravda: The Enemy Banner It will melt like smoke: The truth is behind us, And we will win. These lines belonged to Anna Akhmatova.

3 slide

The first days of the war The war found Akhmatova in Leningrad. Together with her neighbors, she dug cracks in the Sheremetyevsky Garden, was on duty at the gates of the Fountain House, painted beams in the attic of the palace with fireproof lime, and saw the “funeral” of statues in the Summer Garden. The impressions of the first days of the war and the blockade were reflected in the poems “The first long-range fighter in Leningrad”, “The birds of death stand at the zenith...”.

4 slide

THE FIRST LONG-RANGE IN LENINGRAD And in the colorful bustle of humanity, Everything suddenly changed. But it was not a city sound, nor a rural sound. True, it looked like a distant thunderclap, like a brother, But in the thunder there is the humidity of high fresh clouds and the lust of the meadows - news of cheerful showers. And this one was dry as hell, And the confused hearing did not want to Believe - by the way it expanded and grew, How indifferently it brought death to my child. The birds of death are at their zenith. Who is coming to rescue Leningrad? Don't make noise around - he is breathing, He is still alive, he hears everything: Like on the humid Baltic bottom His sons moan in their sleep, Like cries from his depths: “Bread!” They reach the seventh sky... But this firmament is merciless. And looking out of all the windows is death. 1941

5 slide

At the end of September 1941, by order of Stalin, Akhmatova was evacuated outside the blockade ring. Having turned on those fateful days to the people he had tortured with the words “Brothers and sisters...”, the tyrant understood that Akhmatova’s patriotism, deep spirituality and courage would be useful to Russia in the war against fascism. Akhmatova’s poem “Courage” was published in Pravda and then reprinted many times, becoming a symbol of resistance and fearlessness. Courage We know what now lies on the scales And what is happening now. The hour of courage has struck on our watch, And courage will not leave us. It’s not scary to lie under dead bullets, It’s not bitter to be homeless, - And we will save you, Russian speech, the Great Russian word. We will carry you free and clean, And we will give you to your grandchildren, and we will save you from captivity Forever! February 23, 1942 Tashkent Evacuation

6 slide

The poem "Courage" is a call to defend one's homeland. The title of the poem reflects the Author's call to citizens. They must be courageous in defending their state. Anna Akhmatova writes: “We know what is now on the scales.” The fate of not only Russia, but the whole world is at stake, because this World War. The clock struck the hour of courage - the people of the USSR abandoned their tools and took up arms. Next, the author writes about an ideology that really existed: people were not afraid to throw themselves in front of bullets, and almost everyone was left homeless. After all, we need to preserve Russia - Russian speech, the Great Russian word. Anna Akhmatova makes a covenant that the Russian word will be conveyed pure to her grandchildren, that people will come out of captivity without forgetting it. The whole poem sounds like an oath. The solemn rhythm of the verse helps with this - amphibrachic, tetrameter. Only Akhmatova’s exact epithets are key: “free and pure Russian word.” This means that Russia must remain free. After all, what a joy it is to preserve the Russian language, but to become dependent on Germany. But it is needed and pure - without foreign words. You can win a war, but lose your speech.

7 slide

The work of A. Akhmatova during the Great Patriotic War turned out to be in many ways consonant with the official Soviet literature of that time. The poet was encouraged for his heroic pathos: he was allowed to speak on the radio, published in newspapers and magazines, and promised to publish a collection. A. Akhmatova was confused, realizing that she had “pleasing” the authorities. Akhmatova was encouraged for heroism and at the same time scolded for tragedy, so she could not publish some poems, while others - “The enemy’s banner is growing like smoke ...”, “And she who today says goodbye to her beloved ...”, “Courage”, “The First long-range in Leningrad", "Dig, my shovel..." - were published in collections, magazines, newspapers. Image national feat and selfless struggle did not make Akhmatova a “Soviet” poet: something in her work constantly embarrassed the authorities.

8 slide

The poet's lyrics are, first of all, heroic: they are distinguished by a spirit of inflexibility, strong-willed composure and uncompromisingness. In many poems from the beginning of the war, the call to fight and victory sounds openly; Soviet slogans of the 1930s - 1940s are recognizable in them. These works were published and republished dozens of times, for which A. Akhmatova received “extraordinary” fees, calling them “custom-made”. ...The truth is behind us, And we will win. ("Enemy Banner...", 1941). We swear to the children, we swear to the graves, That no one will force us to submit! ("The Oath", 1941). We will not let the adversary into peaceful fields. (“Dig, my shovel...”, 1941).

Slide 9

During the war years, St. Petersburg - Petrograd - Leningrad became the “cultural” hero of Akhmatov’s lyrics, the tragedy of which the poet experienced as deeply personal. In September 1941, the voice of A. Akhmatova sounded on the radio: “For more than a month now, the enemy has been threatening our city with captivity, inflicting heavy wounds on it. The city of Peter, the city of Lenin, the city of Pushkin, Dostoevsky and Blok, the city of great culture and labor, the enemy is threatening death and shame." A. Akhmatova spoke about the “unshakable faith” that the city will never be fascist, about Leningrad women and about conciliarity - the feeling of unity with the entire Russian land.

10 slide

In December 1941, L. Chukovskaya recorded the words of A. Akhmatova, who recalled herself in besieged Leningrad: “I wasn’t afraid of death, but I was afraid of horror. I was afraid that in a second I would see these people crushed... I realized - and it was very humiliating - that I was not ready for death yet. It’s true, I lived unworthy, that’s why I’m not ready yet "

11 slide

A. Akhmatova contrasted the “book” and “real” war; the special quality of the latter, the poet believes, is its ability to generate in people a feeling of the inevitability of death. It’s not a bullet that most likely fights fear, which takes away willpower. By killing the spirit, it deprives a person of the opportunity to internally confront what is happening. Fear destroys heroism. ...And there is no Lenore, and there are no ballads, The Tsarskoye Selo garden is destroyed, And familiar houses stand as if dead. And indifference in the eyes, And foul language on the lips, But just not fear, not fear, Not fear, not fear... Bang, bang! (“And the fathers frothed the mug…”, 1942).

12 slide

In poems dedicated to the Great Patriotic War, at the intersection of the themes of death and memory, the motif of martyrdom arises, which A. Akhmatova associated with the image of warring Leningrad. She wrote about the fate of the city in the “afterwords” to the cycle of poems from 1941 to 1944. After the end of the blockade, the poet changes the cycle, supplements it, removes the previous tragic “afterwords” and renames it “Wind of War”. In the last quatrains of the Leningrad Cycle, A. Akhmatova captured the biblical scene of the crucifixion: as in the Requiem, the most tragic image here is the Mother of God, giving her silence to her Son. ...I give my last and highest joy - My silence - to the Great Martyr Leningrad. ("Afterword", 1944). Wasn’t it me then at the cross, Wasn’t it me who drowned in the sea, Didn’t my lips forget your taste, woe! ("Afterword of the Leningrad Cycle", 1944).

Slide 13

The poems that A. Akhmatova dedicated to her apartment neighbor in the Fountain House, Valya Smirnov, are piercing in their tragic power. The boy died of starvation during the siege. In the works “Knock with your fist - I’ll open it...” (1942) and “In Memory of Valya” (1943), the heroine performs a ritual of remembrance: to remember means not to betray, to save from death. Line five of the poem “Knock…” originally read: “And I’ll never return home.” Trying to avoid the terrible and give way to tragic optimism, A. Akhmatova replaced it with the line “But I will never betray you...”. In the second part, hope for a new spring, the revival of life begins to sound, the motive of redemption, cleansing the world from sin (washing with water) appears, “bloody traces” on the child’s head are the wounds of war and the pricks of the martyr’s crown of thorns.

Slide 14

In 1943, Akhmatova received the medal “For the Defense of Leningrad.” Akhmatova’s poems during the war period are devoid of images of front-line heroism, written from the perspective of a woman who remained in the rear. Compassion and great sorrow were combined in them with a call to courage, a civic note: pain was melted into strength. “It would be strange to call Akhmatova a war poet,” wrote B. Pasternak. “But the predominance of thunderstorms in the atmosphere of the century gave her work a touch of civic significance.” During the war years, a collection of Akhmatova’s poems was published in Tashkent, and the lyrical and philosophical tragedy “Enuma Elish” (When Above...) was written, telling about the cowardly and mediocre arbiters of human destinies, the beginning and end of the world.

15 slide

B. M. Eikhenbaum considered the most important aspect of Akhmatova’s poetic worldview to be “the feeling of her personal life as a national, people’s life, in which everything is significant and universally significant.” “From here,” the critic noted, “an exit into history, into the life of the people, hence a special kind of courage associated with the feeling of being chosen, a mission, a great, important cause...” A cruel, disharmonious world bursts into Akhmatova’s poetry and dictates new themes and new poetics: the memory of history and the memory of culture, the fate of a generation, considered in historical retrospect... Narrative plans of different times intersect, the “alien word” goes into the depths of the subtext, history is refracted through the “eternal” images of world culture, biblical and evangelical motifs.

16 slide

Olga Berggolts wrote about Anna Akhmatova like this: “And so - the war poems of Anna Akhmatova - like the best war poems of our other poets - remain forever alive for us, first of all, because they are true poetry, the poetry that Belinsky spoke about - “not from books, but from life,” that is, inherent in life and man itself and, captured in the transfigured word - most testifying to them - that is, forever being the highest truth of life and man.” And the passionate oath of disobedience, given before children and graves, is not only poetry about courage, but poetry of courage itself.

Slide 17

Second anniversary In 1945, Akhmatova returned to St. Petersburg. Together with her city, the poetess experiences last days war and the period of city restoration. Then she writes “Second Anniversary,” pouring out all her soul, pain and experiences into this poem. No, I didn't cry them out. They boiled inside themselves. And everything passes before my eyes For a long time without them, always without them. . . . . . . . . . . . . . Without them, I am tormented and suffocated by the pain of resentment and separation. Penetrated into the blood - the all-burning salt sobers and dries them. But it seems to me: in forty-four, And not on the first day of June, Your “suffering shadow” appeared erased on silk. Everything was still stamped with the stamp of Great troubles and recent thunderstorms, - And I saw my city Through the rainbow of my last tears. May 31, 1946, Leningrad

18 slide

Poems written during the Great Patriotic War testified to the poet’s ability not to separate the experience of personal tragedy from an understanding of the catastrophic nature of history itself. The war poems of Anna Akhmatova - like the best war poems of our other poets - remain forever alive for us, primarily because they are true poetry.

Slide 19

Lyceum No. 329, St. Petersburg, work of grade 11 B student Malko Margarita, teacher Frolova S.D.

Composition

The theme of the Great Patriotic War runs through the work of many writers and poets. After all, many of them know firsthand about the horrors of war. For example, the poet Sergei Orlov, having started serving as a private, returned from the war as a senior sergeant. In his poems, he expressed the memory of the soldiers who died in battle. In the poem “He was buried in the globe,” the author told us about a simple guy who gave his life, fulfilling his duty to his Motherland. And even though he is one of many on a planetary scale, the established world will be his monument:

The earth is like a mausoleum to him. -

For a million centuries,

And the Milky Ways are gathering dust

Around him from the sides.

Having experienced the hardship of military everyday life, Orlov described them in his poems. Blood, pain, fear of imminent death haunted people in war constantly. But the memories of home, about loved ones warmed the hearts of the fighters. “And your unforgettable and wicked gaze, the gaze that loves forever my fate” - this is what supported them in difficult moments.

K. M. Simonov was a front-line journalist during the war. That is why many of his works are dedicated to war. His famous poem“Wait for me and I will return” was kept in the pockets of many soldiers in their tunics. And even now these lines are known to everyone, because the theme of love and fidelity is always relevant. In another poem, “The Major Brought a Boy on a Carriage,” the author tells how a major, retreating from the Brest Fortress, carries his little son tied to a cannon carriage. A gray-haired boy clutches a toy to himself. Addressing us, Simonov says:

You know this grief firsthand,

And it broke our hearts.

Who ever saw this boy,

He won't be able to come home until the end.

What could be more terrible than a child turning gray from grief and horror.

Other works by Simonov, such as “Death of a Friend”, “Three Brothers”, “Winter of '41” and many others, evoke in us sympathy for people who survived the war. But at the same time, we are proud and admire their courage, their unshakable faith in victory.

Anna Akhmatova did not have a chance to visit the front, but she tasted the bitterness of war in full - her son fought. In her poetry, she conveyed all the pain and grief of mothers, sisters, loved ones, while at the same time instilling faith in victory in their hearts:

And the one who says goodbye to her beloved today -

Let her transform her pain into strength.

We swear to the children, we swear to the graves,

That nothing will force us to submit.

These lines from the poem “The Oath” teach you not to give in to grief, forget about tears, and hope to meet your loved ones.

The most monstrous thing about the war was that innocent children died. This problem was especially close to Akhmatova, as a woman and mother. The poem “In Memory of Valya” evokes tears of compassion in us:

And from your golden head

I will wash away the bloody traces.

But even such a terrible grief did not break the will of the people. People selflessly fought for a just cause, for their native land. The idea of the invincibility of the Russian people was reflected in many of Akhmatova’s war works. These are “Courage” and “In Memory of a Friend”, as well as “Victory”, “Lamentation”, etc.

Akhmatova’s work during the Great Patriotic War

"first manner". Akhmatova approached the beginning of the new trials that awaited the people during the Great Patriotic War with enormous, mature and hard-won experience in civic poetry. The philosophical understanding of time, which had been intensively continuing all these years, was soon reflected in a number of works written during the Great Patriotic War, which in many ways summed up the life path traveled in a different way.

Having raised a wave, a steamer passes.

Oh, is there anything in the world more familiar to me,

Than the spiers shine and shine

The alley turns black like a chink.

Sparrows sit on the wires.

And memorized walks

The salty taste is also not a problem.

The traditional St. Petersburg landscape, well known to us from her previous works, is illuminated in this poem with a kind of gentle smile, dissolving in the glare of the gentle spring sun, the slow movement of waters and the flickering of high spiers. The sundial on the Menshikov House showed two months before the war.

was a new stage in the development of Soviet literature. Over the course of more than twenty years of previous development, she achieved, as we know, serious artistic results. Her contribution to the artistic knowledge of the world lay primarily in the fact that she showed the birth of a person in a new society. During these two decades, Soviet literature gradually included, along with new names; various artists of the older generation. Anna was one of them. Akhmatova. “Like some other writers, she experienced a complex ideological evolution in the 20s and 30s.

The hope of making life easier arose before 1940, when she was allowed to collect and publish a book of selected works. But Akhmatova, naturally, could not include in it any of the poems that directly related to the painful events of those years. Meanwhile, creative growth continued to be very high, and, according to Akhmatova, the poems came in a continuous stream, “stepping on each other’s heels, hurrying and out of breath...”.

Excerpts appeared and initially existed informally, called “strange” by Akhmatova, in which individual features and fragments of the past era arose - right up to 1913, but sometimes the memory of the poem went even further - to the Russia of Dostoevsky and Nekrasov, 1940 was especially special in this regard intense and unusual. Fragments of past eras, scraps of memories, faces of long-dead people persistently came into consciousness, mixing with later impressions and strangely echoing the tragic events of the 30s. However, the poem “The Way of the Whole Earth,” seemingly thoroughly lyrical and deeply tragic in its meaning, also includes colorful fragments of past eras, bizarrely adjacent to the modernity of the pre-war decade. In the second chapter of this poem, the years of youth and almost childhood appear, outbursts of the Black Sea will are heard, at the same time, the reader sees... the trenches of the First World War, and in the penultimate chapter the voices of people appear, pronouncing the latest news about Tsushima, about “ Varyag" and "Korean", that is, about the Russian-Japanese war...

It is not for nothing that Akhmatova wrote that it was precisely from 1940 - from the time of the poem “The Path of All the Earth” and work on “Requiem” that she began to look at the entire past community of events as if from some kind of high tower. During the war years, along with journalistic poems (“Oath”, “Courage”, etc.), Akhmatova also wrote several works of a larger scale, in which she comprehends the entire past historical vastness of the revolutionary time, again returns in memory to the era of 1913, and revises it anew , judges, resolutely rejects many things that were previously dear and close, looking for origins and consequences. This is not a departure into history, but the approach of history to the difficult and difficult day of the war, a unique historical and philosophical understanding of the grandiose war that unfolded before her eyes, which was not characteristic of her alone.

During the war years, readers knew mainly “The Oath” and “Courage” - they were published in newspapers at one time and attracted general attention as a rare example of newspaper journalism from such a chamber poet as A. Akhmatov was in the perception of the majority of the pre-war years. But in addition to these truly wonderful journalistic works, full of Patriotic inspiration and energy, she wrote many other, no longer journalistic, but also in many ways new things for her, such as the poetic cycle “The Moon at its Zenith” (1942-1944), “On Smolensk Cemetery" (1942), "Three Autumns" (1943), "Where on four high paws..." (1943), "Prehistory" (1945) and especially fragments from "Poem without a Hero", begun back in 1940 year, but mostly still voiced by the years of war.