In the year 6619 (1111) ... And on Sunday, when they kissed the cross, they came to Psel, and from there they reached the Golta River. Here they waited for the soldiers, and from there they moved to Vorskla, and there the next day, Wednesday, they kissed the cross and placed all their hope on the cross, shedding copious tears. And from there they crossed many rivers and came to the Don on Tuesday of the sixth week of Lent. And they put on armor, built regiments, and moved towards the city of Sharukan. And Prince Vladimir commanded the priests, riding in front of the army, to sing troparia and kontakions in honor of the Holy Cross and the canon of the Holy Mother of God. And in the evening they drove up to the city, and on Sunday people came out of the city with bows to the Russian princes and brought out fish and wine. And they spent the night there. And the next day, Wednesday, they went to Sugrov and, having started, lit it, and on Thursday they moved from the Don; on Friday, the next day, March 24th, the Polovtsians gathered, built their regiments and went into battle. Our princes, placing their hope in God, said: “Death is here for us, so let us stand strong.” And they said goodbye to each other and, raising their eyes to heaven, called on the Most High God. And when both sides came together, and a fierce battle ensued, God on High turned his gaze, filled with anger, on the foreigners, and they fell before the Christians. And so the foreigners were defeated, and many of our enemies, adversaries, fell before the Russian princes and warriors on the Degei stream. And God helped the Russian princes. And they gave praise to God that day. And the next morning, when Saturday came, they celebrated the resurrection of Lazarus, the day of the Annunciation, and, having given praise to God, spent Saturday and waited for Sunday. On Monday of Holy Week, the foreigners again gathered many of their regiments and moved, like a huge forest, in thousands of thousands. And the Russian regiments surrounded. And the Lord God sent an angel to help the Russian princes. And the Polovtsian regiments and the Russian regiments moved, and the regiments came together in the first battle, and the roar was like thunder. And a fierce battle ensued between them, and people fell on both sides. And Vladimir with his regiments and Davyd began to advance, and, seeing this, the Polovtsians fled. And the Polovtsians fell in front of Vladimirov’s regiment, invisibly killed by an angel, which many people saw, and their heads, invisibly<кем>cut, fell to the ground. And they defeated them on Monday of Holy Week, the month of March on the 27th. Many foreigners were killed on the Salnitsa River. And God saved his people. Svyatopolk, and Vladimir and Davyd glorified God, who had given them such a victory over the filthy, and they took a lot of cattle, and horses, and sheep, and many captives they grabbed with their hands. And they asked the captives, saying: “How did this happen: you were so strong and so numerous, but you could not resist and soon fled?” They answered, saying: “How can we fight with you, when some others rode over you in bright and terrible weapons and helped you?” These could only be angels sent by God to help Christians. It was the angel who gave Vladimir Monomakh the idea of calling his brothers, the Russian princes, against the foreigners...

So now, with God’s help, through the prayers of the Holy Mother of God and the holy angels, the Russian princes returned home to their people with glory, which reached all distant countries - to the Greeks, to the Hungarians, Poles and Czechs, even to Rome it reached the glory To God always, now and forever, amen.

MAIN CHARACTER - MONOMACH

Salnitsa (Russian-Polovtsian wars, XI-XIII centuries). A river in the Don steppes, in the area of which on March 26, 1111, a battle took place between the united army of Russian princes under the command of Prince Vladimir Monomakh (up to 30 thousand people) and the Polovtsian army. The outcome of this bloody and desperate, according to the chronicle, battle was decided by the timely strike of the regiments under the command of princes Vladimir Monomakh and Davyd Svyatoslavich. The Polovtsian cavalry tried to cut off the Russian army's path home, but during the battle they suffered a crushing defeat. According to legend, heavenly angels helped Russian soldiers defeat their enemies. The Battle of Salnitsa was the largest Russian victory over the Cumans. Never since the campaigns of Svyatoslav (10th century) have Russian warriors gone so far into the eastern steppe regions. This victory contributed to the growing popularity of Vladimir Monomakh, the main hero of the campaign, the news of which reached “even Rome.”

CRUSADE IN THE STEPPE OF 1111

This trip started out unusual. When the army prepared to leave Pereyaslavl at the end of February, the bishop and priests stepped forward and carried out a large cross while singing. It was erected not far from the gates of the city, and all the soldiers, including the princes, driving and passing by the cross received the blessing of the bishop. And then, at a distance of 11 miles, representatives of the clergy moved ahead of the Russian army. Subsequently, they walked in the army train, where all the church utensils were located, inspiring Russian soldiers to feats of arms.

Monomakh, who was the inspirer of this war, gave it the character of a crusade modeled on the crusades of Western rulers against the Muslims of the East. The initiator of these campaigns was Pope Urban II. And in 1096, the first crusade of the Western knights began, which ended with the capture of Jerusalem and the creation of the knightly Kingdom of Jerusalem. The sacred idea of liberating the “Holy Sepulcher” in Jerusalem from the hands of infidels became the ideological basis of this and subsequent campaigns of Western knights to the East.

Information about crusade and the liberation of Jerusalem quickly spread throughout the Christian world. It was known that Count Hugo Vermendois, brother of the French king Philip I, son of Anna Yaroslavna, took part in the second crusade, cousin Monomakh, Svyatopolk and Oleg. One of those who brought this information to Rus' was Abbot Daniel, who visited at the beginning of the 12th century. in Jerusalem, and then left a description of his journey about his stay in the crusader kingdom. Daniel was later one of Monomakh’s associates. Perhaps it was his idea to give the campaign of Rus' against the “filthy” the character of a crusade invasion. This explains the role assigned to the clergy in this campaign.

Svyatopolk, Monomakh, Davyd Svyatoslavich and their sons went on a campaign. With Monomakh were his four sons - Vyacheslav, Yaropolk, Yuri and nine-year-old Andrei.…

On March 27, the main forces of the parties converged on the Solnitsa River, a tributary of the Don. According to the chronicler, the Polovtsians “set out like a boar (forest) of greatness and darkness,” they surrounded the Russian army from all sides. Monomakh did not, as usual, stand still, waiting for the onslaught of the Polovtsian horsemen, but led the army towards them. The warriors engaged in hand-to-hand combat. The Polovtsian cavalry in this crowd lost its maneuver, and the Russians began to prevail in hand-to-hand combat. At the height of the battle, a thunderstorm began, the wind increased, and heavy rain began to fall. The Rus rearranged their ranks in such a way that the wind and rain hit the Cumans in the face. But they fought courageously and pushed back the chela (center) of the Russian army, where the Kievans were fighting. Monomakh came to their aid, leaving his “right-hand regiment” to his son Yaropolk. The appearance of Monomakh's banner in the center of the battle inspired the Russians, and they managed to overcome the panic that had begun. Finally, the Polovtsians could not stand the fierce battle and rushed to the Don ford. They were pursued and cut down; No prisoners were taken here either. About ten thousand Polovtsians died on the battlefield, the rest threw down their weapons, asking for their lives. Only a small part, led by Sharukan, went to the steppe. Others went to Georgia, where David IV took them into the service.

The news of the Russian crusade in the steppe was delivered to Byzantium, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Rome. Thus, Rus' at the beginning of the 12th century. became the left flank of Europe's general offensive to the East.

THE ELUSIVE OIL

Salnitsa is mentioned in the chronicle... in connection with the famous campaign of Vladimir Monomakh in 1111, when Konchak’s grandfather, the Polovtsian Khan Sharukan, was killed. This campaign was analyzed by many researchers, but no unanimous opinion was developed on the issue of localizing Salnitsa.

The name of the river is also found in some lists of the Book Big Drawing": "And below Izyum the Salnitsa River fell into Donets on the right side. And below that is Raisin.” Based on these data, V.M. made the first attempt to localize the river mentioned in connection with the campaign of Monomakh in 1111. Tatishchev: “it flows into the Donets from the right side below Izyum.”

In connection with the events of 1185, a similar attempt was made by N.M. Karamzin: “Here the Sal River, which flows into the Don near the Semikarakorsk village, is called Salnitsa.”

In the famous article by P.G. Butkov, where, for the first time, significant attention was paid to many aspects of the geography of Igor Svyatoslavich’s campaign, Salnitsa is identified with the river. Butt. M.Ya. Aristov identified Salnitsa, mentioned in connection with the events of 1111 and 1185, with Thor. Later this opinion was joined by D.I. Bagalei, V.G. Lyaskoronsky. V.A. Afanasiev. M.P. believed approximately the same. Barsov, localizing Salnitsa “not far from the mouth of Oskol.”

K.V. Kudryashov localized the river. Salnitsa in the Izyum region. V.M. Glukhov rightly noted that the mention in the Ipatiev Chronicle (“poidosha to Salnitsa”) could not relate to a small river and the chronicler “could not take it as a geographical landmark.” Famous expert on antiquities of the Podontsov region B.A. Shramko believed that we were talking about two different rivers. V.G. Fedorov, on the contrary, identifies according to V.M. Tatishchev both Salnitsa.

Having analyzed the main hypotheses in detail and put forward additional arguments, M.F. The Hetman clarified that Salnitsa is the old name of the river. Sukhoi Izyumets, flowing into the Seversky Donets opposite the Izyumsky mound.

L.E. Makhnovets distinguishes two Salnitsa rivers: the one mentioned in the description of Monomakh’s campaign in 1111, the scientist with the reservation “obviously” identifies with the river. Solona - the right tributary of the Popilnyushka (the right tributary of the Bereka), and the Salnitsa, associated with Igor’s campaign, traditionally - with the nameless river near Izyum.

In the latest research by Lugansk historian V.I. Podov substantiates the so-called southern version of the location of the theater of military operations. Having identified both Salnitsa, the researcher now localizes one river in the Dnieper basin, believing that this is the modern river. Solona is the right tributary of the river. Volchya flowing into Samara...

It seems to us that the sought-after Salnitsa could be the tributary of the Tor Krivoy Torets. Its upper reaches and the upper reaches of Kalmius are very close, starting from the same hill - the watershed of the Dnieper and Don basins, along which the Muravsky Way passed. Kalmius or one of its tributaries should then be identified with Kayala.

The Polovtsy remained in the history of Rus' the worst enemies of Vladimir Monomakh and cruel mercenaries during the internecine wars. Tribes who worshiped the sky terrorized the Old Russian state for almost two centuries.

"Cumans"

In 1055, Prince Vsevolod Yaroslavich of Pereyaslavl, returning from a campaign against the Torks, met a detachment of new, previously unknown in Rus', nomads led by Khan Bolush. The meeting passed peacefully, the new “acquaintances” received Russian name The “Polovtsians” and future neighbors separated.

Since 1064, Byzantine and 1068 in Hungarian sources mention the Cumans and Kuns, also previously unknown in Europe.

They had to play a significant role in history Eastern Europe, turning into formidable enemies and insidious allies of the ancient Russian princes, becoming mercenaries in a fratricidal civil strife. The presence of the Polovtsians, Cumans, and Kuns, who appeared and disappeared at the same time, did not go unnoticed, and the questions of who they were and where they came from still concern historians to this day.

According to the traditional version, all four of the above-mentioned peoples were a single Turkic-speaking people, which were called differently in various parts Sveta.

Their ancestors - the Sars - lived in the territory of Altai and the eastern Tien Shan, but the state they formed was defeated by the Chinese in 630.

The survivors headed to the steppes of eastern Kazakhstan, where they received a new name “Kipchaks”, which, according to legend, means “ill-fated” and as evidenced by medieval Arab-Persian sources. However, in both Russian and Byzantine sources, Kipchaks are not found at all, and people similar in description are called “Cumans”, “Kuns” or “Polovtsians”. Moreover, the etymology of the latter remains unclear. Perhaps the word comes from the Old Russian “polov”, which means “yellow”. According to scientists, this may indicate that these people had light color hair and belonged to the western branch of the Kipchaks - “Sary-Kipchaks” (Kuns and Cumans belonged to the eastern branch and had a Mongoloid appearance). According to another version, the term “Polovtsy” could come from the familiar word “field”, and designate all the inhabitants of the fields, regardless of their tribal affiliation.

The official version has many weaknesses.

If all nationalities initially represented a single people - the Kipchaks, then how can we explain that this toponym was unknown to Byzantium, Rus', and Europe? In the countries of Islam, where the Kipchaks were known firsthand, on the contrary, they had not heard at all about the Polovtsians or Cumans.

Archeology comes to the aid of the unofficial version, according to which the main archaeological finds Polovtsian culture - stone women erected on mounds in honor of soldiers killed in battle were characteristic only of the Polovtsians and Kipchaks. The Cumans, despite their worship of the sky and the cult of the mother goddess, did not leave such monuments.

All these arguments “against” allow many modern researchers to move away from the canon of studying the Cumans, Cumans and Kuns as the same tribe. According to Candidate of Sciences Yuri Evstigneev, the Polovtsy-Sarys are the Turgesh, who for some reason fled from their territories to Semirechye.

Weapons of civil strife

The Polovtsians had no intention of remaining a “good neighbor” Kievan Rus. As befits nomads, they soon mastered the tactics of surprise raids: they set up ambushes, attacked by surprise, and swept away an unprepared enemy on their way. Armed with bows and arrows, sabers and short spears, the Polovtsian warriors rushed into battle, pelting the enemy with a bunch of arrows as they galloped. They raided the cities, robbing and killing people, taking them captive.

In addition to the shock cavalry, their strength also lay in the developed strategy, as well as in technologies that were new for that time, such as heavy crossbows and “liquid fire,” which they apparently borrowed from China since their time in Altai.

However, as long as centralized power remained in Rus', thanks to the order of succession to the throne established under Yaroslav the Wise, their raids remained only a seasonal disaster, and certain diplomatic relations even began between Russia and the nomads. There was brisk trade and the population communicated widely in the border areas. Dynastic marriages with the daughters of Polovtsian khans became popular among Russian princes. The two cultures coexisted in a fragile neutrality that could not last long.

In 1073, the triumvirate of the three sons of Yaroslav the Wise: Izyaslav, Svyatoslav, Vsevolod, to whom he bequeathed Kievan Rus, fell apart. Svyatoslav and Vsevolod accused their older brother of conspiring against them and striving to become an “autocrat” like their father. This was the birth of a great and long unrest in Rus', which the Polovtsians took advantage of. Without completely taking sides, they willingly sided with the man who promised them big “profits.” Thus, the first prince who resorted to their help, Oleg Svyatoslavich (who was disinherited by his uncles), allowed the Polovtsians to plunder and burn Russian cities, for which he was nicknamed Oleg Gorislavich.

Subsequently, calling the Cumans as allies in internecine struggles became a common practice. In alliance with the nomads, Yaroslav's grandson, Oleg Gorislavich, expelled Vladimir Monomakh from Chernigov, and he took Murom, driving out Vladimir's son Izyaslav from there. As a result, the warring princes faced a real danger of losing their own territories.

In 1097, on the initiative of Vladimir Monomakh, then still Prince of Pereslavl, the Lyubech Congress was convened, which was supposed to put an end to internecine war. The princes agreed that from now on everyone should own their own “fatherland”. Even Kyiv prince, who formally remained the head of state, could not violate the borders. Thus, fragmentation was officially consolidated in Rus' with good intentions. The only thing that united the Russian lands even then was a common fear of Polovtsian invasions.

Monomakh's War

The most ardent enemy of the Polovtsians among the Russian princes was Vladimir Monomakh, under whose great reign the practice of using Polovtsian troops for the purpose of fratricide temporarily ceased. Chronicles, which, however, were actively copied during his time, talk about Vladimir Monomakh as the most influential prince in Rus', who was known as a patriot who spared neither his strength nor his life for the defense of Russian lands. Having suffered defeats from the Polovtsians, in alliance with whom his brother and his worst enemy– Oleg Svyatoslavich, he developed a completely new strategy in the fight against nomads - to fight on their own territory.

Unlike the Polovtsian detachments, which were strong in sudden raids, Russian squads gained an advantage in open battle. The Polovtsian “lava” crashed against the long spears and shields of Russian foot soldiers, and the Russian cavalry, surrounding the steppe inhabitants, did not allow them to escape on their famous light-winged horses. Even the timing of the campaign was thought out: until early spring, when the Russian horses, which were fed with hay and grain, were stronger than the Polovtsian horses that were emaciated on pasture.

Monomakh’s favorite tactics also provided an advantage: he provided the enemy with the opportunity to attack first, preferring defense through foot soldiers, since by attacking, the enemy exhausted himself much more than the defending Russian warrior. During one of these attacks, when the infantry took the brunt of the attack, the Russian cavalry went around the flanks and struck in the rear. This decided the outcome of the battle.

For Vladimir Monomakh, just a few trips to the Polovtsian lands were enough to rid Rus' of the Polovtsian threat for a long time. IN recent years Monomakh sent his son Yaropolk with an army beyond the Don on a campaign against the nomads, but he did not find them there. The Polovtsians migrated away from the borders of Rus', to the Caucasian foothills.

On guard of the dead and the living

The Polovtsians, like many other peoples, have sunk into the oblivion of history, leaving behind “Polovtsian stone women” who still guard the souls of their ancestors. Once upon a time they were placed in the steppe to “guard” the dead and protect the living, and were also placed as landmarks and signs for fords.

Obviously, they brought this custom with them from their original homeland - Altai, spreading it along the Danube.

“Polovtsian Women” is far from the only example of such monuments. Long before the appearance of the Polovtsians, in the 4th-2nd millennium BC, such idols were erected on the territory of present-day Russia and Ukraine by the descendants of the Indo-Iranians, and a couple of thousand years after them - by the Scythians.

“Polovtsian women,” like other stone women, are not necessarily images of women; among them there are many men’s faces. Even the etymology of the word “baba” comes from the Turkic “balbal”, which means “ancestor”, “grandfather-father”, and is associated with the cult of veneration of ancestors, and not at all with female creatures.

Although, according to another version, stone women are traces of a bygone matriarchy, as well as the cult of veneration of the mother goddess among the Polovtsians (Umai), who personified the earthly principle. The only obligatory attribute is the hands folded on the stomach, holding the sacrificial bowl, and the chest, which is also found in men and is obviously associated with feeding the clan.

According to the beliefs of the Cumans, who professed shamanism and Tengrism (worship of the sky), the dead were endowed with special powers that allowed them to help their descendants. Therefore, a Cuman passing by had to offer a sacrifice to the statue (judging by the finds, these were usually rams) in order to gain its support. This is how the 12th century Azerbaijani poet Nizami, whose wife was a Polovtsian, describes this ritual:

“And the Kipchak’s back bends before the idol. The rider hesitates before him, and, holding his horse, He bends down and thrusts an arrow between the grasses. Every shepherd driving away his flock knows that it is necessary to leave the sheep in front of the idol.”

The history of Rus' is full of different events. Each of them leaves its mark in the memory of the entire people. Some key and turning events survive to this day and remain revered and worthy in our society. Take care of yours cultural heritage, remembering great victories and commanders is a very important duty of every person. The Princes of Rus' were not always at their best in terms of their governance of Russia, but they tried to be one family that makes all decisions together. At the most critical and difficult moments there was always a person who “took the bull by the horns” and turned the course of history in reverse side. One of these great people is Vladimir Monomakh, who is still considered an important figure in the history of Rus'. He achieved many complex military-political goals, while he rarely resorted to brutal methods. His methods consisted of tactics, patience and wisdom, which allowed him to reconcile adults who had hated each other for years. In addition, one cannot ignore the prince’s talent for fighting, because Monomakh’s tactics often saved the Russian army from death. Prince Vladimir thought through the defeat of the Polovtsy down to the smallest detail and therefore “trampled” this threat to Rus'.

Polovtsy: acquaintance

The Polovtsy, or Polovtsy, as historians also call them, are a people of Turkic origin who led a nomadic lifestyle. IN different sources they are given different names: in Byzantine documents - Cumans, in Arab-Persian documents - Kipchaks. The beginning of the 11th century turned out to be very productive for the people: they ousted the Torci and Pechenegs from the Volga region and settled in these parts. However, the conquerors decided not to stop there and crossed the Dnieper River, after which they successfully descended to the banks of the Danube. Thus they became the owners of the Great Steppe, which stretched from the Danube to the Irtysh. Russian sources refer to this place as the Polovtsian field.

During the creation of the Golden Horde, the Cumans managed to assimilate many Mongols and successfully impose their language on them. It is worth noting that later this language (Kypchak) was used as the basis for many languages (Tatar, Nogai, Kumyk and Bashkir).

Origin of the term

The word “Polovtsy” from Old Russian means “yellow”. Many representatives of the people had blond hair, but the majority were representatives with an admixture of Mongoloid hair. However, some scientists say that the origin of the name of the people comes from the place where they stopped - the field. There are many versions, but none are reliable.

Tribal system

The defeat of the Polovtsians was partly due to their military-democratic system. The entire people were divided into several clans. Each clan had its own name - the name of the leader. Several clans united into tribes, which created villages and wintering cities for themselves. Each tribal union had its own land on which food was cultivated. There were also smaller organizations, kurens - an association of several families. It is interesting that not only Polovtsy could live in the kurens, but also other peoples with whom natural mixing took place.

Political system

The Kurens united into hordes, headed by a khan. The khans had supreme power locally. In addition to them, there were also categories such as servants and convicts. It should also be noted that women were divided into servants. They were called chagas. Kolodniks were prisoners of war who were essentially house slaves. They did hard work, had no rights and were the lowest rung on the social ladder. There were also koshes - heads of large families. The family consisted of cats. Each kosh is a separate family and its servants.

The wealth gained in battles was divided between the leaders of military campaigns and the nobility. An ordinary warrior received only crumbs from the master's table. In case of an unsuccessful campaign, one could go broke and become completely dependent on some noble Polovtsian.

Military affairs

The military affairs of the Polovtsians were at their best, and even modern scientists admit this. However, history has not preserved much evidence about Polovtsian warriors to this day. It is interesting that any man or youth who was able to simply carry a weapon had to devote his life to military affairs. At the same time, his state of health, physique, and even more so his personal desire were not taken into account. But since such a device has always existed, no one complained about it. It is worth noting that the military affairs of the Cumans were not well organized from the very beginning. It would be more accurate to say that it developed in stages. Historians of Byzantium wrote that these people fought with a bow, curved saber and darts.

Each warrior wore special clothing that reflected his affiliation with the army. It was made from and was quite dense and comfortable. It is interesting that each Cuman warrior had about 10 horses at his disposal.

The main strength of the Polovtsian army was the light cavalry. In addition to the weapons listed above, warriors also fought with sabers and lassos. A little later they had heavy artillery. Such warriors wore special helmets, armor and chain mail. At the same time, they were often made to look very frightening in order to further intimidate the enemy.

It is also worth mentioning the use of heavy crossbows by the Polovtsians, and they most likely learned this in the times when they lived near Altai. It was these capabilities that made the people practically invincible, for few military leaders of that time could boast of such knowledge. The use of Greek fire many times helped the Cumans defeat even very fortified and guarded cities.

It is worth paying tribute to the fact that the army had sufficient maneuverability. But all the successes in this matter came to naught due to the low speed of movement of the troops. Like all nomads, the Cumans won many victories thanks to sharp and unexpected attacks on the enemy, lengthy ambushes and deceptive maneuvers. They often targeted small villages as targets of attack, which would not have been able to provide the necessary resistance, much less defeat the Polovtsians. However, the army was often defeated due to the lack of professional fighters. Not much attention was paid to training the younger ones. It was possible to learn any skills only during a raid, when the main activity was practicing primitive combat techniques.

Russian-Polovtsian wars

The Russian-Polovtsian wars are a long series of serious conflicts that played out for approximately a century and a half. One of the reasons was the clash of territorial interests of both sides, because the Cumans were a nomadic people who wanted to conquer new lands. The second reason was that Rus' was going through difficult times of fragmentation, so some rulers recognized the Cumans as allies, causing the anger and indignation of other Russian princes.

The situation was quite sad until Vladimir Monomakh intervened, who set his initial goal to unite all the lands of Rus'.

Background to the Battle of Salnitsa

In 1103, the Russian princes carried out their first campaign against the nomadic people in the steppe. By the way, the defeat of the Polovtsians took place after the Dolob Congress. In 1107, Russian troops successfully defeated Bonyaki and Sharukan. Success instilled the spirit of rebellion and victory in the souls of Russian warriors, so already in 1109, the Kiev governor Dmitr Ivorovich tore to pieces large Polovtsian villages near the Donets.

Monomakh's tactics

It is worth noting that the defeat of the Polovtsians (date - March 27, 1111) was one of the first in modern list Memorable dates military history RF. The victory of Vladimir Monomakh and other princes was a calculated political victory that had far-sighted consequences. The Russians prevailed despite the fact that the advantage in quantitative terms was almost one and a half.

Today, many are interested in the stunning defeat of the Polovtsians under which prince became achievable? The enormous and invaluable merit of the contribution of Vladimir Monomakh, who skillfully used his gift as a commander. He took several important steps. Firstly, he implemented the good old principle, which states that the enemy must be destroyed on his territory and with little loss of life. Secondly, he successfully used the transport capabilities of that time, which made it possible to timely deliver infantry soldiers to the battlefield, while preserving their strength and spirit. The third reason for Monomakh's thoughtful tactics was that he even resorted to weather conditions to achieve the desired victory - he forced the nomads to fight in weather that did not allow them to fully use all the advantages of their cavalry.

However, this is not the prince’s only merit. Vladimir Monomakh thought out the defeat of the Polovtsy down to the smallest detail, but in order to implement the plan, it was necessary to achieve the almost impossible! First, let's plunge into the mood of that time: Rus' was fragmented, the princes held on to their territories with their teeth, everyone tried to do their own thing, and everyone believed that only he was right. However, Monomakh managed to gather, reconcile and unite wayward, rebellious or even stupid princes. It is very difficult to imagine how much wisdom, patience and courage the prince needed... He resorted to tricks, tricks and direct persuasion, which could somehow influence the princes. The result was gradually achieved, and civil strife ceased. It was at the Dolob Congress that the main agreements and agreements were reached between different princes.

The defeat of the Polovtsians by Monomakh also occurred due to the fact that he convinced other princes to involve even the Smerds in order to strengthen the army. Previously, no one even thought about this, because only combatants were supposed to fight.

The defeat at Salnitsa

The campaign began on the second Sunday of Great Lent. On February 26, 111, the Russian army under the command of an entire coalition of princes (Svyatopolk, David and Vladimir) headed towards Sharukani. It is interesting that the march of the Russian army was accompanied by the singing of songs, accompanied by priests and crosses. From this, many researchers of the history of Rus' conclude that the campaign was a crusade. It is believed that this was a thoughtful move by Monomakh to raise morale, but most importantly, to inspire the army that it can kill and must win, for God himself tells them to do so. In fact, Vladimir Monomakh turned this great battle of the Russians against the Polovtsians into a righteous battle for the Orthodox faith.

The army reached the battlefield only after 23 days. The hike was difficult, but thanks morale, songs and a sufficient amount of provisions, the army was satisfied, which means it was in full combat readiness. On the 23rd day, the warriors reached the shores

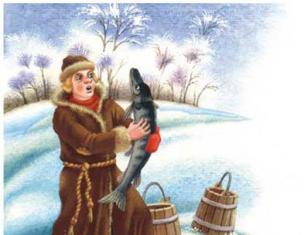

It is worth noting that Sharukan surrendered without a fight and quite quickly - already on the 5th day of the brutal siege. Residents of the city offered wine and fish to the invaders - a seemingly insignificant fact, but it indicates that the people conducted here. The Russians also burned Sugrov. The two settlements that were destroyed bore the names of khans. These are exactly the two cities that the army fought with in 1107, but then Khan Sharukan fled from the battlefield, and Sugrov became a prisoner of war.

Already on March 24, the first initial battle took place, in which the Cumans invested all their strength. It took place near the Donets. The defeat of the Polovtsians by Vladimir Monomakh occurred later, when a battle took place on the Salnitsa River. Interestingly, the moon was full. This was the second and most important battle between the two sides, in which the Russians prevailed.

The largest defeat of the Polovtsians by the Russian armies, the date of which is already known, shook up the entire Polovtsian people, because the latter had great numerical advantage in battle. They were confident that they would win, however, they could not withstand the thoughtful and direct blow of the Russian army. For the people and soldiers, the defeat of the Polovtsians by Vladimir Monomakh was a very joyful and cheerful event, because good booty was obtained, many future slaves were captured, and most importantly, a victory was won!

Consequences

The consequences of this great event were dramatic. The defeat of the Polovtsians (1111) became a turning point in the history of the Russian-Polovtsian wars. After the battle, the Polovtsy decided to approach the borders of the Russian principality only once. It’s interesting that they did this after Svyatopolk passed away (two years after the battle). However, the Polovtsians established contact with the new prince Vladimir. In 1116, the Russian army made another campaign against the Polovtsians and captured three cities. The final defeat of the Polovtsians broke their fighting spirit, and they soon went into the service of the Georgian king David the Builder. The Kipchaks did not respond to the last Russian campaign, which confirmed their final decline.

A few years later, Monomakh sent Yaropolk in search of the Polovtsy beyond the Don, but there was no one there.

Sources

Many Russian chronicles tell about this event, which became key and significant for the entire people. The defeat of the Polovtsians by Vladimir strengthened his power, as well as the people’s faith in their strength and their prince. Despite the fact that the Battle of Salnitsa is partially described in many sources, the most detailed “portrait” of the battle can only be found in

Extremely important event was the defeat of the Polovtsians. This turn of events came in handy for Rus'. And all this became possible thanks to the efforts of Vladimir Monomakh. How much strength and intelligence he put into ridding Rus' of this scourge! How carefully he thought through the course of the entire operation! He knew that the Russians always acted as victims, because the Polovtsians attacked first, and the population of Rus' could only defend themselves. Monomakh realized that he should attack first, because this would create the effect of surprise, and also transfer the warriors from the state of defenders to the state of attackers, which is more aggressive and strong in the general mass. Realizing that the nomads begin their campaigns in the spring, since they have practically no foot soldiers, he scheduled the defeat of the Polovtsians at the end of winter in order to deprive them main force. In addition, such a move had other advantages. They consisted in the fact that the weather deprived the Polovtsy of their maneuverability, which was simply impossible in winter conditions. It is believed that the Battle of Salnitsa and the defeat of the Cumans in 1111 was the first major and well-thought-out victory of Ancient Rus', which became possible thanks to commander's talent Vladimir Monomakh.

Contents of the article:

Polovtsy (Polovtsians) are a nomadic people who were once considered the most warlike and powerful. The first time we hear about them is in history lessons at school. But the knowledge that a teacher can give within the framework of the program is not enough to understand who they are, these Polovtsians, where they came from and how they influenced the life of Ancient Rus'. Meanwhile, for several centuries they haunted the Kyiv princes.

History of the people, how they came into being

Polovtsy (Polovtsians, Kipchaks, Cumans) are nomadic tribes, the first mention of which dates back to 744. Then the Kipchaks were part of the Kimak Kaganate, ancient state nomads formed on the territory of modern Kazakhstan. The main inhabitants here were the Kimaks, who occupied eastern lands. The lands near the Urals were occupied by the Polovtsians, who were considered relatives of the Kimaks.

By the middle of the 9th century, the Kipchaks achieved superiority over the Kimaks, and by the middle of the 10th century they absorbed them. But the Polovtsians decided not to stop there and by the beginning of the 11th century, thanks to their belligerence, they moved close to the borders of Khorezm ( historical region Republic of Uzbekistan).

At that time, the Oghuz (medieval Turkic tribes) lived here, who, due to the invasion, had to move to Central Asia.

By the middle of the 11th century, the Kipchaks submitted to almost the entire territory of Kazakhstan. The western borders of their possessions reached the Volga. Thus, thanks to active nomadic life, raids and the desire to conquer new lands, the once small group of people occupied vast territories and became one of the strongest and richest among the tribes.

Lifestyle and social organization

Their socio-political organization was a typical military-democratic system. The entire people were divided into clans, the names of which were given by the names of their elders. Each clan owned land plots and summer nomadic routes. The heads were the khans, who were also the heads of certain kurens (small divisions of the clan).

The wealth obtained during the campaigns was divided among representatives of the local elite participating in the campaign. Ordinary people, unable to feed themselves, became dependent on the aristocrats. Poor men were engaged in herding livestock, while women served as servants of local khans and their families.

There are still disputes over the appearance of the Polovtsians; the study of the remains continues using modern capabilities. Today scientists have some portrait of these people. It is assumed that they did not belong to the Mongoloid race, but were more like Europeans. The most characteristic feature is blondness and reddishness. Scientists from many countries agree on this.

Independent Chinese experts also describe the Kipchaks as people with blue eyes and “red” hair. There were, of course, dark-haired representatives among them.

War with the Cumans

In the 9th century, the Cumans were allies of the Russian princes. But soon everything changed; at the beginning of the 11th century, Polovtsian troops began to regularly attack the southern regions of Kievan Rus. They plundered houses, took captives, who were then sold into slavery, and took away livestock. Their invasions were always sudden and brutal.

In the middle of the 11th century, the Kipchaks stopped fighting the Russians, as they were busy at war with the steppe tribes. But then they took up their task again:

- In 1061, the Pereyaslavl prince Vsevolod was defeated in a battle with them and Pereyaslavl was completely destroyed by nomads;

- After this, wars with the Polovtsians became regular. In one of the battles in 1078, the Russian prince Izyaslav died;

- In 1093, the army gathered by three princes to fight the enemy was destroyed.

These were hard times for Rus'. Endless raids on villages ruined the already simple farming of the peasants. Women were taken captive and became servants, children were sold into slavery.

In order to somehow protect the southern borders, the residents began to build fortifications and settle there the Turks, who were military force princes.

Campaign of Seversky Prince Igor

Sometimes the Kyiv princes went on an offensive war against the enemy. Such events usually ended in victory and caused great damage to the Kipchaks, briefly cooling their ardor and giving the border villages the opportunity to restore their strength and life.

But there were also unsuccessful trips. An example of this is the campaign of Igor Svyatoslavovich in 1185.

Then he, uniting with other princes, went out with an army to the right tributary of the Don. Here they encountered the main forces of the Polovtsians, and a battle ensued. But the enemy’s numerical superiority was so noticeable that the Russians were immediately surrounded. Retreating in this position, they came to the lake. From there, Igor rode to the aid of Prince Vsevolod, but was unable to carry out his plans, as he was captured and many soldiers died.

It all ended with the fact that the Polovtsians were able to destroy the city of Rimov, one of the large ancient cities Kursk region and defeat the Russian army. Prince Igor managed to escape from captivity and returned home.

His son remained in captivity, who returned later, but in order to gain freedom, he had to marry the daughter of a Polovtsian khan.

Polovtsy: who are they now?

On at the moment there is no unambiguous data on the genetic similarity of the Kipchaks with any people living today.

There are small ethnic groups considered to be distant descendants of the Cumans. They are found among:

- Crimean Tatars;

- Bashkir;

- Kazakhov;

- Nogaitsev;

- Balkartsev;

- Altaytsev;

- Hungarians;

- Bulgarian;

- Polyakov;

- Ukrainians (according to L. Gumilev).

Thus, it becomes clear that the blood of the Polovtsians flows today in many nations. The Russians were no exception, given their rich joint history.

To tell about the life of the Kipchaks in more detail, it is necessary to write more than one book. We touched on its brightest and most important pages. After reading them, you will better understand who they are - the Polovtsians, what they are known for and where they came from.

Video about nomadic peoples

In this video, historian Andrei Prishvin will tell you how the Cumans arose in the territory ancient Rus':

The lesson was truly harsh. The Donetsk Polovtsians, defeated by Vladimir Monomakh, became silent. There were no invasions on their part either the next year or the year after. But Khan Bonyak continued his raids, albeit without the same scope, and cautiously. In the late autumn of 1105, he suddenly appeared at the Zarubinsky Ford, not far from Pereyaslavl, plundered the Dnieper villages and villages and quickly retreated. The princes did not even have time to gather the chase. In the next 1106, the Polovtsians attacked Rus' three times already, but the raids were unsuccessful and did not bring any booty to the steppe inhabitants. First they approached the town of Zarechsk, but were driven away by the Kyiv squads. According to the chronicler, Russian soldiers drove the Polovtsians “to the Danube” and “took away everything.” Then Bonyak “fought” near Pereyaslavl and hastily retreated. Finally, according to the chronicler, “Bonyak and Sharukan the Old and many other princes came and stood near Lubn.” The Russian army moved towards them, but the Polovtsians, not accepting the fight, “ran, grabbing their horses.”

These raids did not pose a serious danger to Rus'; they were easily repelled by the princely squads, but the Polovtsian activity could not be underestimated. The Polovtsy began to recover from the recent defeat, and it was necessary to prepare a new big campaign in the steppe. Or, if Bonyak and Sharukan get ahead, we will meet them with dignity at the borders of Russian soil.

In August 1107, a large Polovtsian army besieged Luben, Sharukan brought with him the surviving Don Polovtsians, Khan Bonyak brought the Dnieper Polovtsians, and they were joined by the khans of other Polovtsian hordes. But since the summer, in the Pereyaslav fortress there were squads of many Russian princes who gathered at the call of Vladimir Monomakh. They rushed to the aid of the besieged city, crossed the Sulu River on the move and suddenly struck the Polovtsians. Those, without even displaying their battle banners, rushed in all directions: some did not have time to take their horses and fled to the steppe on foot, abandoning their full and looted booty. Monomakh ordered the cavalry to relentlessly pursue them so that there would be no one to attack Rus' again. Bonyak and Sharukan barely escaped. The pursuit continued to the Khorol River, through which Sharukan managed to cross, sacrificing the soldiers covering his flight. The spoils of the winners were many horses, which would serve the Russian soldiers well in future campaigns in the steppe.

Political significance this victory was great. In January 1108, the khans of Aepa’s large horde, wandering not far from the borders of Kievan Rus, proposed concluding a treaty of peace and love. The treaty was accepted by the Russian princes. As a result, the unity of the khans disintegrated, and conditions were created for the final defeat of Sharukan and his allies. But preparing a new all-Russian campaign in the steppes required considerable time, and Sharukan could not be given a break. And in the winter of 1109, Vladimir Monomakh sent his governor Dmitry Ivorovich to the Donets with the Pereyaslav cavalry squad and foot soldiers on sleighs. He was ordered to find out exactly where the Polovtsian camps were located in winter, whether they were ready for summer campaigns against Rus', and whether Sharukan had many warriors and horses left. The Russian army had to devastate the Polovtsian vezhi, so that Sharukan would know: even in winter there would be no rest for him while he was at enmity with Russia.

Voivode Dmitry fulfilled the prince's instructions. Pedestrians in sleighs and warriors on horseback quickly passed through the steppes and at the beginning of January were already on the Donets. There they were met by the Polovtsian army. The governor put up a tried-and-tested close formation of foot soldiers against the Polovtsian cavalry, against which the attack of the archers was broken, and the defeat was again completed by the flank attacks of the mounted warriors. The Polovtsians fled, abandoning their tents and property. Thousands of tents and many prisoners and livestock became the prey of Russian soldiers. No less valuable was the information brought by the governor from the Polovtsian steppes. It turned out that Sharukan was standing on the Don and gathering forces for a new campaign against Rus', exchanging messengers with Khan Bonyak, who was also preparing for war on the Dnieper.

In the spring of 1110, the united squads of princes Svyatopolk, Vladimir Monomakh and David advanced to the steppe border and stood near the city of Voinya. The Polovtsy went there from the steppe, but, unexpectedly meeting a Russian army ready for battle, they turned back and got lost in the steppes. The Polovtsian invasion did not take place.

The new campaign in the steppe was prepared for a long time and in detail. The Russian princes met again on Lake Dolobsky to discuss the plan for the campaign. The opinions of the governors were divided: some proposed to wait until next spring to move to the Donets in boats and on horses, others - to repeat the winter sleigh ride of the governor Dmitr, so that the Polovtsians could not migrate south and fatten their horses, weakened during the winter lack of food, on spring pastures. The latter were supported by Vladimir Monomakh and his word turned out to be decisive. The start of the hike was scheduled for the very end of winter, when the frosts would subside, but there would still be an easy sleigh path.

At the end of February, armies from Kyiv, Smolensk, Chernigov, Novgorod-Seversky and other cities met in Pereyaslavl. The great Kiev prince Svyatopolk with his son Yaroslav, the sons of Vladimir Monomakh - Vyacheslav, Yaropolk, Yuri and Andrey, David Svyatoslavich of Chernigov with his sons Svyatoslav, Vsevolod, Rostislav, the sons of Prince Oleg - Vsevolod, Igor, Svyatoslav arrived. It has been a long time since so many Russian princes gathered for a joint war. Again, numerous armies of foot soldiers, who had proven themselves so well in previous campaigns against the Polovtsians, joined the princely equestrian squads.

On February 26, 1111, the army set out on a campaign. The princes stopped on the Alta River, waiting for the late squads. On March 3, the army reached the Suda River, having covered about one hundred and forty miles in five days. Considering that foot soldiers and large sleigh convoys with weapons and supplies were moving along with the mounted squads, such pace of the march should be considered very significant - thirty miles per day's march!

It was hard to walk. The thaw began, the snow was quickly melting, the horses had difficulty pulling the loaded sleigh. And yet the speed of the march almost did not decrease. Only a well-trained and resilient army was capable of such transitions.

On the Khorol River, Vladimir Monomakh ordered the sleigh train to be left and weapons and supplies to be loaded into packs. Then we walked lightly. The Wild Field began - the Polovtsian steppe, where there were no Russian settlements. The army covered the thirty-eight-mile journey from Khorol to the Psel River in one day's march. Ahead lay the Vorskla River, on which the Russian governors knew convenient fords - this was very important, since the deep spring rivers posed a serious obstacle. Horse guards rode far ahead of the main forces to prevent a surprise attack by the Polovtsians. On March 7, the Russian army reached the shores of Vorskla. On March 14, the army reached the Donets, repeating the winter campaign of the governor Dmitry. Beyond lay the “unknown land” - the Russian squads had never gone that far. The Polovtsian horse patrols flashed ahead - the horde of Khan Sharukan was somewhere close. The Russian soldiers put on their armor and assumed a battle formation: “brow”, regiments of the right and left hands, and a guard regiment. So they moved on, in battle formation, ready to meet the Polovtsian attack at any moment. The Donets remained behind, and Sharukan appeared - a steppe city consisting of hundreds of tents, tents, and low adobe houses. For the first time, the Polovtsian capital saw enemy banners under its walls. Sharukan was clearly not prepared for defense. The rampart around the city was low, easily surmountable - apparently, the Polovtsians considered themselves completely safe, hoping that they were reliably protected by the expanses of the Wild Field... Residents sent ambassadors with gifts and requests not to destroy the city, but to accept the ransom that the Russian princes would appoint.

Vladimir Monomakh ordered the Polovtsians to surrender all weapons, release prisoners, and return property looted in previous raids. Russian squads entered Sharukan. This happened on March 19, 1111.

The Russian army stood in Sharukan for only one night, and in the morning it moved on to the Don, to the next Polovtsian town - Sugrov. Its residents decided to defend themselves by taking to the earthen rampart with weapons. Russian regiments surrounded Sugrov on all sides and bombarded him with arrows containing burning, tarred tow. Fires started in the city. The distraught Polovtsians rushed through the burning streets, trying to cope with the fire. Then the attack began. Russian soldiers used heavy timber rams to break through the city gates and entered the city. Sugrov fell. The robber's nest, from which in previous years dashing bands of Polovtsian horsemen flew out for the next raid, ceased to exist.

There was only half a day's march left to the Don River... Meanwhile, patrol patrols discovered a large concentration of Polovtsians on the Solnitsa River (Tor River), a tributary of the Don. A decisive battle was approaching, the result of which could only be victory or death: the Russian army had gone so far into the Wild Field that it was impossible to escape from the fast Polovtsian cavalry in the event of a retreat.

The day arrived on March 24, 1111. Dense crowds of Polovtsians appeared on the horizon, throwing forward the tentacles of light-horse patrols. The Russian army adopted a battle formation: in the “brow” - Grand Duke Svyatopolk with his Kyivians; on the right wing - Vladimir Monomakh and his sons with Pereyaslavl, Rostov, Suzdal, Belozer, Smolyans; on the left wing - Chernigov princes. The proven Russian battle formation with an indestructible phalanx of infantry in the center and fast cavalry squads on the flanks...

This is how Vladimir Monomakh fought in 1076 with knightly cavalry in the Czech Republic - pawn-spearmen in the center and cavalry on the flanks - and won. This is how he built his army in the last big campaign against the Polovtsians and also gained the upper hand. This is how, many years later, another glorious knight of the “Yaroslav family” - Alexander Nevsky - will arrange his regiments, when he leads his warriors onto the ice of Lake Peipus to push back the German dog knights...

Only at the end of the day the Polovtsians gathered for an attack and rushed into the Russian formation in huge crowds. The experienced Sharukan abandoned the usual Polovtsian tactics - striking the forehead with a horse wedge - and advanced along the entire front so that the horse squads of the princes could not help the footmen with flank attacks. The brutal slaughter began immediately both in the “forehead” and on the wings. Russian warriors had difficulty holding back the Polovtsian onslaught.

Probably, the khan was mistaken in building the battle this way. His warriors, many of whom had no armor, were not accustomed to “direct combat”, to close hand-to-hand combat and carried huge losses. The Russians held out and began to slowly move forward. It was getting dark quickly. The Polovtsians, realizing that they could not crush the Russian army with a frantic onslaught, turned their horses and galloped off into the steppe. This was a success for the Russian princes, but it was not yet a victory: many Polovtsian horsemen were saved and could continue the war. This is how Vladimir Monomakh assessed the situation, sending a guard regiment after the Polovtsians. Sharukan will gather his steppe army somewhere, we need to find out where...

The Russian regiments stood on the battlefield for only one day. Sentry patrols reported that the Polovtsians were again gathering in crowds near the mouth of Solnitsa. The Russian regiments set out on a campaign and marched all night. The fires of a huge Polovtsian camp were already flickering ahead.

The morning of March 27, 1111 arrived. Both troops again faced each other. This time Sharukan did not seek luck in the terrible “direct battle”, in which the Russians turned out to be invincible, but tried to surround the regiments of the princes from all sides in order to shoot the warriors from afar with bows, taking advantage of the speed of the Polovtsian horses and enormous numerical superiority. But Vladimir Monomakh did not allow his army to be encircled and he himself decisively moved forward. This was a surprise for the Polovtsian military leaders: usually the Russians waited to be attacked, and only after repelling the blow did they launch counterattacks. The Polovtsians were forced to take “direct battle” again. The leader of the Russian army imposed his will on the enemy. Once again the Polovtsian cavalry attacked the center of the Russian formation, and again the pawn-spearmen held out, giving the cavalry squads the opportunity to strike on the flanks. The Pereyaslav squad under the banner of Vladimir Monomakh fought in decisive sectors of the battle, instilling fear in the enemies. The horse squads of other princes broke into the Polovtsian ranks and tore the Polovtsian system to pieces. The khans and thousands rushed about in vain, trying to establish control of the battle. The Polovtsians huddled together in discordant crowds, moved randomly across the field, beaten by Russian warriors who were invulnerable in their armor. And the spirit of the Polovtsian army broke, it rolled back, towards the Don Ford. Frightened by this spectacle, thousands of fresh Polovtsians stopped on the other side of the Don. Horse squads relentlessly pursued the retreating Polovtsians, mercilessly cutting them down with long swords. Ten thousand warriors of Khan Sharukan found their deaths on the Don shore, and many were captured. The defeat was complete. There is no time for raids on Rus' now for the khan...

News of the victory of the Russian princes on the Don thundered across the Polovtsian steppes. Khan Bonyak was afraid, took his Dnieper Polovtsians away from the Russian borders, and in Rus' it was not even known where he was and what he was doing. The remnants of the Don Polovtsians migrated to the Caspian Sea, and some even further - beyond the “Iron Gates” (Derbent). Great silence fell on the steppe border of Rus', and this was the main result of the campaign. Rus' received a long-awaited respite.