Half a century ago something happened that was hard to believe - a man flew into space. Astronauts are heroes of a bygone generation, but their names are still remembered today. Few people know, but space was far from peaceful for humans; it was given in blood. Dead astronauts, hundreds of test officers and soldiers who died in explosions and fires during rocket testing. Needless to say about the thousands of nameless military personnel who died while performing routine work - crashed, burned alive, poisoned with heptyl. And, despite this, unfortunately, not everyone was satisfied. Flight into space is an extremely dangerous and complex job: the people who perform it will be discussed in this article...

Komarov Vladimir Mikhailovich

Pilot-cosmonaut, engineer-colonel, twice Hero of the Soviet Union. He flew on Voskhod-1 and Soyuz-1 more than once. He was the commander of the first three-man crew in history. Komarov died on April 24, 1967, when, at the end of the flight program, during descent to Earth, the parachute of the descent vehicle did not open, as a result of which the structure with the officer on board crashed into the ground at full speed.

Dobrovolsky Georgy Timofeevich

Soviet cosmonaut, Air Force lieutenant colonel, Hero of the Soviet Union. Died on June 30, 1971 in the stratosphere over Kazakhstan. The cause of death is considered to be depressurization of the Soyuz-11 lander, probably due to valve failure. He had a huge number of prestigious awards, including the Order of Lenin.

Patsaev Viktor Ivanovich

Pilot-cosmonaut of the USSR, Hero of the Soviet Union, the world's first astronomer who was lucky enough to work outside the earth's atmosphere. Patsayev was part of the same crew as Dobrovolsky; he died with him on June 30, 1971 due to a leak in the oxygen valve of the Soyuz-11.

Scobie Francis Richard

NASA astronaut, has flown twice space flights on the Challenger shuttle. He was among those killed in space as a result of the STS-51L accident along with his crew. The launch vehicle with the shuttle exploded 73 seconds after launch, with 7 people on board. The cause of the disaster is considered to be burnout of the solid fuel accelerator wall. Francis Scobee was posthumously inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame.

Resnick Judith Arlen

The American female astronaut spent about 150 hours in space, was part of the crew of the same ill-fated Challenger shuttle and died during its launch on January 28, 1986 in Florida. At one time she was the second woman to fly into space.

Anderson Michael Phillip

American aerospace engineer computer technology, US pilot-astronaut, Air Force lieutenant colonel. During his life he flew more than 3,000 hours on various jet aircraft. Died while returning from space aboard the Columbia STS-107 spacecraft on February 1, 2003. The disaster occurred at an altitude of 63 kilometers above Texas. Anderson and six of his colleagues, after 15 days in orbit, burned to death just 16 minutes before landing.

Ramon Ilan

Israeli Air Force pilot, Israel's first astronaut. Tragically died on February 1, 2003 during the destruction of the same shuttle Columbia STS-107, which crashed in the dense layers of the earth’s atmosphere.

Grissom Virgil Ivan

The world's first commander of a two-seater spacecraft. Unlike the previous participants in the rating, this astronaut died on Earth, during the preparatory stage of the flight, a month before the scheduled launch of Apollo 1. On January 27, 1967, a fire in an atmosphere of pure oxygen occurred at the Kennedy Space Center during training, where Virgil Griss and two of his colleagues died.

Bondarenko Valentin Vasilievich

Died under very similar circumstances on March 23, 1961. He was on the list of the first 20 astronauts who were selected for the first space flight in history. During the tests of cold and loneliness in the pressure chamber, his training woolen suit caught fire as a result of an accident, and the man died from the burns eight hours later.

Adams Michael James

American test pilot, US Air Force astronaut. He was among those killed in space during his seventh suborbital flight on the X-15 in 1967. For unknown reasons, the aircraft Adams was on board was completely destroyed more than 50 miles above the surface of the earth. The causes of the accident still remain unknown; all telemetry information was lost along with the remains of the rocket plane.

The Soviet manned space program, which began with triumphs, began to falter in the second half of the 1960s. Stung by failures, the Americans threw enormous resources into competition with the Russians and began to get ahead Soviet Union.

Passed away in January 1966 Sergei Korolev, the man who was the main driver of the Soviet space program. In April 1967, a cosmonaut died during a test flight of the new Soyuz spacecraft. Vladimir Komarov. On March 27, 1968, Earth's first cosmonaut died while performing a training flight on an airplane. Yuri Gagarin. Sergei Korolev's latest project, the N-1 lunar rocket, suffered one failure after another during testing.

The cosmonauts involved in the manned “lunar program” wrote letters to the CPSU Central Committee asking for permission to fly on their own responsibility, despite the high probability of disaster. However, the country's political leadership did not want to take that risk. The Americans were the first to land on the Moon, and the Soviet “lunar program” was curtailed.

The participants in the failed conquest of the Moon were transferred to another project - a flight to the world's first manned orbital station. A manned laboratory in orbit should have allowed the Soviet Union to at least partially compensate for the defeat on the Moon.

Crews for Salyut

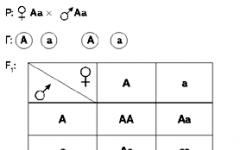

In the approximately four months that the first station could operate in orbit, it was planned to send three expeditions to it. Crew number one included Georgy Shonin, Alexey Eliseev And Nikolay Rukavishnikov, the second crew was Alexey Leonov, Valery Kubasov, Petr Kolodin, crew number three - Vladimir Shatalov, Vladislav Volkov, Victor Patsayev. There was also a fourth, reserve crew, consisting of Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vitaly Sevastyanov And Anatoly Voronov.

The commander of crew number four, Georgy Dobrovolsky, seemed to have no chance of getting to the first station, called Salyut. But fate had a different opinion on this matter.

Georgy Shonin grossly violated the regime, and the chief curator of the Soviet cosmonaut detachment, General Nikolay Kamanin suspended him from further training. Vladimir Shatalov was transferred to Shonin’s place, he himself was replaced by Georgy Dobrovolsky, and the fourth crew was introduced Alexey Gubarev.

On April 19, the Salyut orbital station was launched to low-Earth orbit. Five days later, the Soyuz-10 ship returned to the station with a crew consisting of Shatalov, Eliseev and Rukavishnikov. The docking with the station, however, took place abnormally. The crew could not transfer to Salyut, nor could they undock. As a last resort, it was possible to undock by detonating the squibs, but then not a single crew would be able to get to the station. With great difficulty, it was possible to find a way to take the ship away from the station while keeping the docking port intact.Soyuz-10 returned safely to Earth, after which engineers began hastily modifying the docking units of Soyuz-11.

Forced substitution

A new attempt to conquer the Salyut was to be made by the crew consisting of Alexey Leonov, Valery Kubasov and Pyotr Kolodin. The start of their expedition was scheduled for June 6, 1971.

During the wire to Baikonur, the plate that Leonov threw to the ground for luck did not break. The awkwardness was hushed up, but the bad feelings remained.

According to tradition, two crews flew to the cosmodrome - the main and backup. The understudies were Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsaev.

SOYUZ-11 "Soyuz-11" on the launch pad. Photo: RIA Novosti / Alexander Mokletsov

This was a formality, since until then no last-minute substitutions had been made.

But three days before the start, doctors found a darkening in Valery Kubasov’s lungs, which they considered to be the initial stage of tuberculosis. The verdict was categorical - he couldn’t go on a flight.

The state commission decided: what to do? The commander of the main crew, Alexei Leonov, insisted that if Kubasov could not fly, then he needed to be replaced with backup flight engineer Vladislav Volkov.

Most experts, however, believed that in such conditions it was necessary to replace the entire crew. The backup crew also opposed the partial replacement. General Kamanin wrote in his diaries that the situation had become seriously tense. Two crews usually went to the traditional pre-flight meeting. After the commission approved the replacement, and Dobrovolsky’s crew became the main one, Valery Kubasov announced that he would not go to the rally: “I’m not flying, what should I do there?” Kubasov still showed up at the rally, but tension was in the air.

Soviet cosmonauts (from left to right) Vladislav Volkov, Georgy Dobrovolsky and Viktor Patsayev at the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Photo: RIA Novosti / Alexander Mokletsov

“If this is compatibility, then what is incompatibility?”

Journalist Yaroslav Golovanov, who wrote a lot on the topic of space, recalled what was happening these days at Baikonur: “Leonov was tearing and throwing... poor Valery (Kubasov) did not understand anything at all: he felt absolutely healthy... At night he came to the hotel Petya Kolodin, drunk and completely down. He told me: “Slava, understand, I will never fly into space again...”.

On June 6, 1971, Soyuz-11 with a crew of Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev successfully launched from Baikonur. The ship docked with Salyut, the cosmonauts boarded the station, and the expedition began.

Reports in the Soviet press were bravura - everything was going according to the program, the crew was feeling good. In reality, things were not so smooth. After landing, when studying the crew’s work diaries, they found Dobrovolsky’s note: “If this is compatibility, then what is incompatibility?”Flight engineer Vladislav Volkov, who had space flight experience behind him, often tried to take the initiative, which was not very popular with the specialists on Earth, and even with his fellow crew members.

On the 11th day of the expedition, a fire broke out on board, and there was a question of emergency leaving the station, but the crew still managed to cope with the situation.

General Kamanin wrote in his diary: “At eight in the morning Dobrovolsky and Patsayev were still sleeping, Volkov got in touch, who yesterday, according to Bykovsky’s report, was the most nervous of all and “yaked” too much (“I decided...”, “I did ..." etc). On behalf of Mishin, he was given instructions: “Everything is decided by the crew commander, follow his orders,” to which Volkov replied: “We decide everything as a crew. We will figure out what to do ourselves.”

“The connection ends. Happily!"

Despite all the difficulties and the difficult situation, the Soyuz-11 crew fully completed the flight program. On June 29, the cosmonauts were supposed to undock from Salyut and return to Earth.

After the return of Soyuz-11, the next expedition was supposed to go to the station to secure achievements achieved and continue experiments.

But before undocking with Salyut, a problem arose new problem. The crew had to close the transfer hatch in the descent module. But the “Hatch is open” banner on the control panel continued to glow. Several attempts to open and close the hatch yielded nothing. The astronauts were under great stress. Earth advised placing a piece of insulation under the limit switch of the sensor. This was done repeatedly during testing. The hatch was closed again. To the delight of the crew, the banner went out. The pressure in the service compartment was released. According to the instrument readings, we were convinced that no air was escaping from the descent vehicle and its tightness was normal. After this, Soyuz-11 successfully undocked from the station.

At 0:16 on June 30, General Kamanin contacted the crew, reporting the landing conditions, and ending with the phrase: “See you soon on Earth!”

“I understand, the landing conditions are excellent. Everything is in order on board, the crew is feeling excellent. Thank you for your concern and good wishes", answered Georgy Dobrovolsky from orbit.

Here is a recording of the last negotiations between the Earth and the Soyuz-11 crew:

Zarya (Mission Control Center): How is the orientation going?

“Yantar-2” (Vladislav Volkov): We saw the Earth, we saw it!

"Zarya": Okay, don't rush.

"Yantar-2": "Zarya", I am "Yantar-2". We started orientation. The rain is hanging on the right.

"Yantar-2": Flies great, beautiful!

“Yantar-3” (Viktor Patsayev): “Zarya”, I’m third. I can see the horizon along the lower edge of the window.

“Zarya”: “Yantar”, I remind you once again of the orientation - zero - one hundred and eighty degrees.

"Yantar-2": Zero - one hundred and eighty degrees.

"Zarya": We understood correctly.

"Yantar-2": The "Descent" banner is lit.

"Zarya": Let it burn. Everything is fine. It burns correctly. The connection ends. Happily!"

“The outcome of the flight is the most difficult”

At 1:35 Moscow time, after the orientation of the Soyuz, the braking propulsion system was turned on. After completing the estimated time and losing speed, the ship began to leave orbit.

During the passage of dense layers of the atmosphere there is no communication with the crew; it should appear again after the parachute of the descent vehicle is deployed, due to the antenna on the parachute line.

At 2:05 a.m. a report was received from the Air Force command post: “The crews of the Il-14 aircraft and the Mi-8 helicopter see the Soyuz-11 ship descending by parachute.” At 2:17 the lander landed. Almost simultaneously, four search group helicopters landed.

Doctor Anatoly Lebedev, who was part of the search group, recalled that he was confused by the silence of the crew on the radio. The helicopter pilots conducted active radio communications at the moment while the descent vehicle was landing, and the astronauts did not go on the air. But this was attributed to antenna failure.

“We sat down after the ship, about fifty to a hundred meters away. What happens in such cases? You open the hatch of the descent vehicle, and from there - the voices of the crew. And here - the crunch of scale, the sound of metal, the chatter of helicopters and... silence from the ship,” the medic recalled.When the crew was taken out of the descent module, doctors could not understand what had happened. It seemed that the astronauts simply lost consciousness. But upon a quick examination, it became clear that everything was much more serious. Six doctors began performing artificial respiration and chest compressions.

Minutes passed, the search group commander, General Goreglyad demanded an answer from the doctors, but they continued to try to bring the crew back to life. Finally, Lebedev replied: “Tell me that the crew landed without signs of life.” This wording was included in all official documents.

Doctors continued resuscitation measures until absolute signs of death appeared. But their desperate efforts could not change anything.

The Mission Control Center was first reported that “the outcome of the space flight is the most difficult.” And then, having abandoned any kind of conspiracy, they reported: “The entire crew was killed.”

Depressurization

It was a terrible shock for the whole country. At the farewell in Moscow, the comrades of the deceased cosmonauts cried and said: “Now we are burying entire crews!” It seemed that the Soviet space program had completely failed.

The specialists, however, had to work even at such a moment. What happened in those minutes when there was no communication with the astronauts? What killed the crew of Soyuz 11?

The word “depressurization” sounded almost immediately. We remembered the emergency situation with the hatch and checked for leaks. But her results showed that the hatch is reliable, it had nothing to do with it.

But it really was a matter of depressurization. An analysis of the records of the Mir autonomous on-board measurement recorder, a kind of “black box” of the spacecraft, showed: from the moment the compartments were separated at an altitude of more than 150 km, the pressure in the descent module began to decrease sharply, and within 115 seconds dropped to 50 millimeters of mercury.

These indicators indicated the destruction of one of the ventilation valves, which is provided in case the ship lands on water or lands with the hatch down. The supply of life support system resources is limited, and so that the astronauts do not experience a lack of oxygen, the valve “connected” the ship to the atmosphere. It should have worked during landing in normal mode only at an altitude of 4 km, but this happened at an altitude of 150 km, in a vacuum.

Forensic medical examination showed traces of brain hemorrhage, blood in the lungs, damage to the eardrums and the release of nitrogen from the blood of the crew members.

From the report of the medical service: “50 seconds after the separation, Patsayev’s respiratory rate was 42 per minute, which is characteristic of acute oxygen starvation. Dobrovolsky's pulse quickly drops, and breathing stops by this time. This initial period of death. At the 110th second after separation, all three have no recorded pulse or breathing. We believe that death occurred 120 seconds after separation.”

The crew fought to the end, but had no chance of salvation

The hole in the valve through which the air escaped was no more than 20 mm, and, as some engineers said, it could “just be plugged with your finger.” However, this advice was practically impossible to implement. Immediately after depressurization, fog formed in the cabin, and a terrible whistle of escaping air sounded. Just a few seconds later, the astronauts began to experience terrible pain throughout their bodies due to acute decompression sickness, and then they found themselves in complete silence due to burst eardrums.

But Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev fought to the end. All transmitters and receivers in the Soyuz-11 cabin were turned off. The shoulder belts of all three crew members were unfastened, but Dobrovolsky's belts were mixed up and only the upper waist buckle was fastened. Based on these signs, an approximate picture of the last seconds of the astronauts’ lives was reconstructed. To determine the place where the depressurization occurred, Patsayev and Volkov unfastened their seat belts and turned off the radio. Dobrovolsky may have managed to check the hatch, which had problems during undocking. Apparently, the crew managed to realize that the problem was in the ventilation valve. It was not possible to plug the hole with a finger, but it was possible to close the emergency valve manually using a valve. This system was made in case of landing on water, to prevent flooding of the descent vehicle.On Earth, Alexey Leonov and Nikolai Rukavishnikov participated in an experiment trying to determine how long it takes to close a valve. The cosmonauts, who knew where trouble would come from, were prepared for it and were not in real danger, needed significantly more time than the Soyuz-11 crew had. Doctors believe that consciousness began to fade in such conditions after about 20 seconds. However, the rescue valve was partially closed. One of the crew began to spin it, but lost consciousness.

After Soyuz-11, the cosmonauts were again dressed in spacesuits

The reason for the abnormal opening of the valve was considered to be a defect in the manufacture of this system. Even the KGB got involved in the case, seeing possible sabotage. But no saboteurs were found, and besides, on Earth it was not possible to experimentally repeat the situation of abnormal valve opening. As a result, this version was left final due to the lack of a more reliable one.

Spacesuits could have saved the cosmonauts, but on the personal orders of Sergei Korolev their use was discontinued, starting with Voskhod 1, when this was done to save space in the cabin. After the Soyuz-11 disaster, a controversy erupted between the military and engineers - the former insisted on the return of the spacesuits, and the latter argued that this emergency was an exceptional case, while the introduction of spacesuits would sharply reduce the possibilities for delivering payload and increasing the number of crew members.

Victory in the discussion remained with the military, and, starting with the flight of Soyuz-12, domestic cosmonauts fly only in spacesuits.

The ashes of Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev were buried in the Kremlin wall. The program of manned flights to the Salyut-1 station was curtailed.

The next manned flight to the USSR took place more than two years later. Vasily Lazarev And Oleg Makarov new spacesuits were tested on Soyuz-12.

The failures of the late 1960s and early 1970s were not fatal for the Soviet space program. By the 1980s, the Soviet Union's space exploration program through orbital stations had once again become a world leader. During flights, emergency situations and serious accidents occurred, but people and equipment rose to the occasion. Since June 30, 1971, disasters with human casualties there was none in the domestic cosmonautics.

P.S. The diagnosis of tuberculosis made to cosmonaut Valery Kubasov turned out to be erroneous. The darkening in the lungs was a reaction to the flowering of the plants, and soon disappeared. Kubasov, together with Alexei Leonov, took part in a joint flight with American astronauts under the Soyuz-Apollo program, as well as in a flight with the first Hungarian cosmonaut Bertalan Farkas.

In the space thriller "" viewers are faced with the terrifying prospect of an astronaut flying in airless space. The film started October with a record-breaking $55.6 million weekend gross. Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as astronauts find themselves suspended in nowhere after space debris (which is in orbit) crashes their craft. .

"Gravity"'s spectacular depiction of cosmic disaster may be fictional, but the potential for death and destruction in space is far from being fully realized, says Allan J. McDonald, a NASA engineer.

"It's an extremely dangerous activity," MacDonald says.

Before you are the largest real disasters in the history of space exploration. Including ones similar to the one in “Gravity”. Everything as you like: with sacrifices, with crumbling metal and tears of loved ones. Just not the Hollywood version.

Valentina Nikolaeva (left) - a cosmonaut by choice - joins the crowd on Red Square and applauds three new Russian cosmonauts October 19, 1964. From left to right: Boris Egorov, Konstantin Feoktistov and Vladimir Komarov.

The first fatal accident in space occurred with the Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov: the Soyuz-1 capsule fell onto Russian soil in 1967. KGB sources (Starman, 2011, Walker & Co.) say that Komarov and others knew the capsule would crash, but the Soviet leadership ignored their warnings.

Various points of view agree that the cause of the accident was a faulty parachute. Audio recordings of the astronaut's final conversations with ground control indicate that the astronaut was "furiously yelling" at engineers whom he blamed for the malfunction of the spacecraft.

Deaths in space

Soyuz 11 cosmonauts Viktor Patsaev, Georgy Dobrovolsky and Vladislav Volkov are being tested in a flight simulator. NASA

The Soviet space program was the first (and so far only) to encounter death in space in 1971, when cosmonauts Georgy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev and Vladislav Volkov died while returning to Earth from the Salyut 1 space station. Their Soyuz 11 spacecraft made a textbook-perfect landing in 1971. Therefore, the rescue team was surprised to find three people dead, sitting on couches, with dark blue marks on their faces, and blood dripping from their noses and ears.

An investigation showed that a ventilation valve burst and the astronauts suffocated. The collapse in pressure doomed the crew to death from the vacuum of space - and they became the only human creatures ever to face such a fate. The people died within seconds of the valve rupture, which occurred at an altitude of 168 kilometers, and became the first and so far the last astronauts to die in space. As the capsule moved along automatic program landing, the ship was able to land without living pilots.

Challenger disaster

Challenger crew members: astronauts Michael J. Smith, Francis R. Scobee and Ronald E. McNair, Allison S. Onizuka, loading specialists Sharon Crystal McAuliffe and Gregory Jarvis, and Judith A. Resnick

NASA ended the Apollo era without fatal accidents during space missions. The streak of success came to an abrupt end on January 28, 1986, when the space shuttle Challenger exploded in front of numerous television viewers shortly after liftoff. The launch attracted a lot of attention because it was the first time a teacher had gone into orbit. By promising to teach lessons from space, Christa McAuliffe attracted an audience of millions of schoolchildren.

The disaster traumatized the nation, said James Hansen, a space historian at Ober University.

"That's what makes Challenger unique," he said. - “We saw it. We saw that this would continue to happen.”

A noisy investigation revealed that the O-ring had deteriorated due to low temperatures on launch day. NASA knew this could happen. The accident led to technical and cultural changes at the agency and stalled the shuttle program until 1988.

Space Shuttle Columbia tragedy

Shuttle Columbia re-entered the atmosphere and disintegrated

Seventeen years after the Challenger tragedy, the shuttle program faced another loss when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry on February 1, 2003, at the end of mission STS-107.

The investigation showed that the cause of the destruction of the shuttle was a piece of thermal insulation of the oxygen tank, which damaged the thermal insulation of the wing during launch. The seven crew members may have survived the shuttle's initial damage, but they quickly lost consciousness and died as the shuttle continued to crash around them. The Columbia shuttle disaster, according to MacDonald, unfortunately repeats the mistakes of the Challenger era, and some little thing remains unaddressed.

The following year, President George W. Bush announced the end of the shuttle program.

Apollo 1 fire

Astronauts (from left) Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee pose in front of Launch Complex 34

Although no astronauts were lost in space during the Apollo mission, two fatal incidents occurred during flight preparations. Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Edward White II and Roger Chaffee died during a "non-hazardous" ground test of the command module on January 27, 1967. A fire broke out in the cabin and three astronauts suffocated before their bodies were engulfed in flames.

The investigation found several errors were made, including the use of pure oxygen in the cabin, flammable Velcro and an inward-opening hatch that left the crew trapped. Before the test, the astronauts showed concern about the cabin and posed in front of the apparatus.

As a result of the accident, Congress conducted investigations that could have canceled the Apollo program but ultimately led to design and procedural changes that benefited future missions, Hansen said.

"If the fire hadn't happened, many people say we wouldn't have reached the moon," he says.

Apollo 13: "Houston, we have a problem"

Astronaut John L. Swigert Jr., the Apollo 13 command module pilot, holds the jerry-rigged tool that the Apollo 13 astronauts built to use lithium hydroxide canisters in the command module to clear carbon dioxide from the lunar module. gas

The Apollo program owes its success in part to savvy actions that prevented disasters. In 1966, the agency successfully docked the Gemini 8 spacecraft to its target vehicle, but Gemini went into an uncontrolled spin. A rotation rate of one revolution per second could have caused astronauts Neil Armstrong and David Scott to lose consciousness. Fortunately, Armstrong corrected the situation by shutting down the faulty main engine and taking control of the engines to enter the dense atmosphere.

In 1995, a film called "Apollo 13" was released, which was based on real case on the spaceship of the same name, which could leave the astronauts in airless space. An oxygen tank exploded, damaging the service module and making it impossible to land on the Moon. To get home, the astronauts used the slingshot principle, accelerating the ship using the gravity of the Moon and sending it towards Earth. After the explosion, astronaut Jack Swigert radioed mission control with the phrase, “Houston, we had a problem.” In film catchphrase goes to Jim Lowell, played by Tom Hanks, and sounds in a slightly modified version: “Houston, we have a problem.”

Lightning and Wolves

The bright sun shines over the Apollo 12 base on the surface of the Moon. One of the astronauts walks away from the Intrepid lunar module

Both NASA and the USSR/Russia space programs encountered several interesting, although not catastrophic, events. In 1969, lightning struck the same spacecraft twice, at 36 and 52 seconds after Apollo 12's launch. The mission went smoothly.

Due to a 46-second delay caused by the cramped cabin, cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Pavel Belyaev on Voskhod 2 slightly missed their re-entry point. The device crashed into the forests of the Upper Kama region, replete with wolves and bears. Leonov and Belyaev spent the night almost freezing, clutching a pistol in case of an attack (which did not happen).

"What if?". Nixon's speech on Apollo 11

Collage photo of President Richard M. Nixon and astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin after their legendary moon landing on July 20, 1969

Perhaps the most stunning cosmic disasters have never happened - except in the minds of people carefully planning them. History remembers the potential disaster thanks to a speech written for President Richard Nixon in case Apollo 11 astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong got stuck on the Moon during the first manned landing on Earth's satellite.

The text reads: “It is destined by fate that the men who set out peacefully to explore the Moon will rest in peace on the Moon.”

If this happened, the future space flights and the public's perception could be very different from what it is now, Hansen says.

“If we on Earth thought about dead bodies on the surface of the moon... the specter of it would haunt us. Who knows, maybe this led to the closure of the space program."

Well, it’s hard to say at what cost NASA would have paid for missions to Venus and Mars.

There are only about 20 people who gave their lives for the benefit of world progress in the field of space exploration, and today we will tell about them.

Their names are immortalized in the ashes of cosmic chronos, burned into the atmospheric memory of the universe forever, many of us would dream of remaining heroes for humanity, however, few would want to accept such a death as our cosmonaut heroes.

The 20th century was a breakthrough in mastering the path to the vastness of the Universe; in the second half of the 20th century, after much preparation, man was finally able to fly into space. However, there was also back side such rapid progress - death of astronauts.

People died during pre-flight preparations, during the takeoff of the spacecraft, and during landing. Total during space launches, preparations for flights, including cosmonauts and technical personnel who died in the atmosphere More than 350 people died, about 170 astronauts alone.

Let us list the names of the cosmonauts who died during the operation of spacecraft (the USSR and the whole world, in particular America), and then we will briefly tell the story of their death.

Not a single cosmonaut died directly in Space; most of them all died in the Earth’s atmosphere, during the destruction or fire of the ship (the Apollo 1 astronauts died while preparing for the first manned flight).

Volkov, Vladislav Nikolaevich (“Soyuz-11”)

Dobrovolsky, Georgy Timofeevich (“Soyuz-11”)

Komarov, Vladimir Mikhailovich (“Soyuz-1”)

Patsaev, Viktor Ivanovich (“Soyuz-11”)

Anderson, Michael Phillip ("Columbia")

Brown, David McDowell (Columbia)

Grissom, Virgil Ivan (Apollo 1)

Jarvis, Gregory Bruce (Challenger)

Clark, Laurel Blair Salton ("Columbia")

McCool, William Cameron ("Columbia")

McNair, Ronald Erwin (Challenger)

McAuliffe, Christa ("Challenger")

Onizuka, Allison (Challenger)

Ramon, Ilan ("Columbia")

Resnick, Judith Arlen (Challenger)

Scobie, Francis Richard ("Challenger")

Smith, Michael John ("Challenger")

White, Edward Higgins (Apollo 1)

Husband, Rick Douglas (Columbia)

Chawla, Kalpana (Columbia)

Chaffee, Roger (Apollo 1)

It is worth considering that we will never know the stories of the death of some astronauts, because this information is secret.

Soyuz-1 disaster

“Soyuz-1 is the first Soviet manned spacecraft (KK) of the Soyuz series. Launched into orbit on April 23, 1967. There was one cosmonaut on board Soyuz-1 - Hero of the Soviet Union, engineer-colonel V. M. Komarov, who died during the landing of the descent module. Komarov’s backup in preparation for this flight was Yu. A. Gagarin.”

Soyuz-1 was supposed to dock with Soyuz-2 to return the crew of the first ship, but due to problems, the launch of Soyuz-2 was canceled.

After entering orbit, problems began with the operation of the solar battery; after unsuccessful attempts to launch it, it was decided to lower the ship to Earth.

But during the descent, 7 km from the ground, the parachute system failed, the ship hit the ground at a speed of 50 km per hour, tanks with hydrogen peroxide exploded, the cosmonaut died instantly, Soyuz-1 almost completely burned out, the remains of the cosmonaut were severely burned so that it was impossible to identify even fragments of the body.

“This disaster was the first time a person died in flight in the history of manned astronautics.”

The causes of the tragedy have never been fully established.

Soyuz-11 disaster

Soyuz 11 is a spacecraft whose crew of three cosmonauts died in 1971. The cause of death was the depressurization of the descent module during the landing of the ship.

Just a couple of years after the death of Yu. A. Gagarin (himself famous astronaut died in a plane crash in 1968), having seemingly followed the well-trodden path of conquest outer space, several more astronauts passed away.

Soyuz-11 was supposed to deliver the crew to the Salyut-1 orbital station, but the ship was unable to dock due to damage to the docking unit.

Crew composition:

Commander: Lieutenant Colonel Georgy Dobrovolsky

Flight engineer: Vladislav Volkov

Research engineer: Viktor Patsayev

They were between 35 and 43 years old. All of them were posthumously awarded awards, certificates, and orders.

It was never possible to establish what happened, why the spacecraft was depressurized, but most likely this information will not be given to us. But it’s a pity that at that time our cosmonauts were “guinea pigs” who were released into space without much security or security after the dogs. However, probably many of those who dreamed of becoming astronauts understood what a dangerous profession they were choosing.

Docking occurred on June 7, undocking on June 29, 1971. There was an unsuccessful attempt to dock with the Salyut-1 orbital station, the crew was able to board the Salyut-1, even stayed on board for several days orbital station, a TV connection was established, but already during the first approach to the station, the cosmonauts noticed some smoke. On the 11th day, a fire started, the crew decided to descend on the ground, but problems emerged that disrupted the undocking process. Spacesuits were not provided for the crew.

On June 29 at 21.25 the ship separated from the station, but a little more than 4 hours later contact with the crew was lost. The main parachute was deployed, the ship landed in a given area, and the soft landing engines fired. But the search team discovered at 02.16 (June 30, 1971) the lifeless bodies of the crew; resuscitation efforts were unsuccessful.

During the investigation, it was found that the cosmonauts tried to eliminate the leak until the last minute, but they mixed up the valves, fought for the wrong one, and meanwhile missed the opportunity for salvation. They died from decompression sickness - air bubbles were found during autopsy even in the heart valves.

The exact reasons for the depressurization of the ship have not been named, or rather, they have not been announced to the general public.

Subsequently, engineers and creators of spacecraft, crew commanders took into account many tragic mistakes of previous unsuccessful flights into space.

Challenger shuttle disaster

“The Challenger disaster occurred on January 28, 1986, when the space shuttle Challenger, at the very beginning of mission STS-51L, was destroyed by the explosion of its external fuel tank 73 seconds into flight, resulting in the death of all 7 crew members. The crash occurred at 11:39 EST (16:39 UTC) over the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of central Florida, USA."

In the photo, the ship's crew - from left to right: McAuliffe, Jarvis, Resnik, Scobie, McNair, Smith, Onizuka

All of America was waiting for this launch, millions of eyewitnesses and viewers watched the launch of the ship on TV, it was the culmination of the Western conquest of space. And so, when the grand launch of the ship took place, seconds later, a fire began, later an explosion, the shuttle cabin separated from the destroyed ship and fell at a speed of 330 km per hour on the surface of the water, seven days later the astronauts would be found in the broken cabin at the bottom of the ocean. Until the last moment, before hitting the water, some crew members were alive and tried to supply air to the cabin.

There is an excerpt in the video below the article live broadcast with the launch and death of the shuttle.

“The Challenger shuttle crew consisted of seven people. Its composition was as follows:

The crew commander is 46-year-old Francis “Dick” R. Scobee. US military pilot, US Air Force Lieutenant Colonel, NASA astronaut.

The co-pilot is 40-year-old Michael J. Smith. Test pilot, US Navy captain, NASA astronaut.

The scientific specialist is 39-year-old Ellison S. Onizuka. Test pilot, Lieutenant Colonel of the US Air Force, NASA astronaut.

The scientific specialist is 36-year-old Judith A. Resnick. Engineer and NASA astronaut. Spent 6 days 00 hours 56 minutes in space.

The scientific specialist is 35-year-old Ronald E. McNair. Physicist, NASA astronaut.

The payload specialist is 41-year-old Gregory B. Jarvis. Engineer and NASA astronaut.

The payload specialist is 37-year-old Sharon Christa Corrigan McAuliffe. A teacher from Boston who won the competition. For her, this was her first flight into space as the first participant in the “Teacher in Space” project.”

Last photo of the crew

To establish the causes of the tragedy, various commissions were created, but most of the information was classified; according to assumptions, the reasons for the ship’s crash were poor interaction between organizational services, irregularities in the operation of the fuel system that were not detected in time (the explosion occurred at launch due to the burnout of the wall of the solid fuel accelerator), and even. .terrorist attack. Some said that the shuttle explosion was staged to harm America's prospects.

Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

“The Columbia disaster occurred on February 1, 2003, shortly before the end of its 28th flight (mission STS-107). The final flight of the space shuttle Columbia began on January 16, 2003. On the morning of February 1, 2003, after a 16-day flight, the shuttle was returning to Earth.

NASA lost contact with the craft at approximately 14:00 GMT (09:00 EST), 16 minutes before its intended landing on Runway 33 at the John F. Kennedy Space Center in Florida, which was scheduled to take place at 14:16 GMT. Eyewitnesses filmed burning debris from the shuttle flying at an altitude of about 63 kilometers at a speed of 5.6 km/s. All 7 crew members were killed."

Crew pictured - From top to bottom: Chawla, Husband, Anderson, Clark, Ramon, McCool, Brown

The Columbia shuttle was making its next 16-day flight, which was supposed to end with a landing on Earth, however, as the main version of the investigation says, the shuttle was damaged during the launch - a piece of torn off thermal insulating foam (the coating was intended to protect tanks with oxygen and hydrogen) as a result of the impact, damaged the wing coating, as a result of which, during the descent of the apparatus, when the heaviest loads on the body occur, the apparatus began to overheat and, subsequently, destruction.

Even during the shuttle mission, engineers more than once turned to NASA management to assess the damage and visually inspect the shuttle body using orbital satellites, but NASA experts assured that there were no fears or risks and the shuttle would descend safely to Earth.

“The crew of the shuttle Columbia consisted of seven people. Its composition was as follows:

The crew commander is 45-year-old Richard “Rick” D. Husband. US military pilot, US Air Force colonel, NASA astronaut. Spent 25 days 17 hours 33 minutes in space. Before Columbia, he was commander of the shuttle STS-96 Discovery.

The co-pilot is 41-year-old William "Willie" C. McCool. Test pilot, NASA astronaut. Spent 15 days 22 hours 20 minutes in space.

The flight engineer is 40-year-old Kalpana Chawla. Scientist, first female NASA astronaut of Indian origin. Spent 31 days, 14 hours and 54 minutes in space.

The payload specialist is 43-year-old Michael P. Anderson. Scientist, NASA astronaut. Spent 24 days 18 hours 8 minutes in space.

Zoology specialist - 41-year-old Laurel B. S. Clark. US Navy captain, NASA astronaut. Spent 15 days 22 hours 20 minutes in space.

Scientific specialist (doctor) - 46-year-old David McDowell Brown. Test pilot, NASA astronaut. Spent 15 days 22 hours 20 minutes in space.

The scientific specialist is 48-year-old Ilan Ramon (English Ilan Ramon, Hebrew.אילן רמון). NASA's first Israeli astronaut. Spent 15 days 22 hours 20 minutes in space.”

The shuttle's descent took place on February 1, 2003, and within an hour it was supposed to land on Earth.

“On February 1, 2003, at 08:15:30 (EST), the space shuttle Columbia began its descent to Earth. At 08:44 the shuttle began to enter the dense layers of the atmosphere." However, due to damage, the leading edge of the left wing began to overheat. From 08:50, the ship's hull suffered severe thermal loads; at 08:53, debris began to fall off the wing, but the crew was alive and there was still communication.

At 08:59:32 the commander sent the last message, which was interrupted mid-sentence. At 09:00, eyewitnesses had already filmed the explosion of the shuttle, the ship collapsed into many fragments. that is, the fate of the crew was predetermined due to NASA’s inaction, but the destruction and loss of life occurred in a matter of seconds.

It is worth noting that the Columbia shuttle was used many times, at the time of its death the ship was 34 years old (in operation by NASA since 1979, the first manned flight in 1981), it flew into space 28 times, but this flight turned out to be fatal.

No one died in space itself, in the dense layers of the atmosphere and in spaceships- about 18 people.

In addition to the disasters of 4 ships (two Russian - "Soyuz-1" and "Soyuz-11" and American - "Columbia" and "Challenger"), in which 18 people died, there were several more disasters due to an explosion, fire during pre-flight preparation , one of the most famous tragedies is a fire in an atmosphere of pure oxygen during preparation for the Apollo 1 flight, then three American astronauts died, and in a similar situation, a very young USSR cosmonaut, Valentin Bondarenko, died. The astronauts simply burned alive.

Another NASA astronaut, Michael Adams, died while testing the X-15 rocket plane.

Yuri Alekseevich Gagarin died in an unsuccessful flight on an airplane during a routine training session.

Probably, the goal of the people who stepped into space was grandiose, and it is not a fact that even knowing their fate, many would have renounced astronautics, but still we always need to remember at what cost the path to the stars was paved for us...

The photo shows the monument to the dead cosmonauts on the moon

Warm June day in 1971. The Soyuz 11 descent module made its planned landing. At mission control, everyone applauded, eagerly awaiting the crew's appearance on the air. At that moment, no one yet suspected that the Soviet cosmonautics would soon be shaken by the biggest tragedy in its entire history.

Long preparation for the flight

Between 1957 and 1975, there was intense competition between the USSR and the United States in the field of space exploration. After three unsuccessful launches of the N-1 rocket, it became clear: the Soviet Union lost to the Americans in the lunar race. Work in this direction was quietly closed down, concentrating on the construction of orbital stations.

The first Salyut spacecraft was successfully launched into orbit in the winter of 1971. The next goal was divided into four stages: prepare the crew, send them to the station, successfully dock with it and then conduct a series of studies in outer space for several weeks.

The docking of the first Soyuz 10 spacecraft was unsuccessful due to malfunctions in the docking unit. Nevertheless, the astronauts managed to return to Earth, and their task fell on the shoulders of the next crew.

Its commander, Alexey Leonov, visited the design bureau every day and looked forward to the launch. However, fate decreed otherwise. Three days before the flight, flight engineer Valery Kubasov’s doctors discovered a strange spot on an X-ray of his lungs. There was no time left to clarify the diagnosis, and it was necessary to urgently look for a replacement.

The question of who will now fly into space was being decided in power circles. The State Commission made its choice at the very last moment, only 11 hours before the launch. Her decision was extremely unexpected: the crew was completely changed, and now Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov and Viktor Patsayev were going into space.

Life on Salyut 1: what awaited the cosmonauts at the Salyut OKS

The launch of Soyuz 11 took place on June 6, 1971 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. At that time, pilots went into space in ordinary flight suits, because the design of the ship did not allow for the use of spacesuits. If there was any oxygen leak, the crew was doomed.

The next day after the launch, the difficult docking stage began. On the morning of June 7, the remote control activated the program responsible for rendezvous with the Salyut station. When no more than 100 meters remained to it, the crew switched to manual control of the ship and an hour later successfully docked with the OKS.

"The crew of Soyuz-11.

After that it started new stage space exploration - now there was a full-fledged scientific station in orbit. Dobrovolsky transmitted news of the successful docking to Earth, and his team began re-opening the premises.

The astronauts' schedule was detailed. Every day they conducted research and biomedical experiments. Television reports from the Earth were regularly carried out directly from the station.

On June 26 (i.e. exactly 20 days later), the crew of Soyuz 11 became a new record holder for flight range and duration of stay in space. There are 4 days left until the end of their mission. Communication with the Control Center was stable, and there were no signs of trouble.

The journey home and the tragic death of the crew

On June 29, the order to complete the mission came. The crew transferred all research records aboard Soyuz 11 and took their places. The undocking was successful, which Dobrovolsky reported to the Control Center. Everyone was in high spirits. Vladislav Volkov even joked on air: “See you on Earth, and prepare some cognac.”

After disconnection, the flight proceeded as planned. The braking system was launched in a timely manner, and the descent module separated from the main compartment. After this, communication with the crew stopped.

Those who were expecting the astronauts on Earth were not particularly alarmed. When the ship enters the atmosphere, a wave of plasma rolls across its hull and the communication antennas burn out. Just a normal situation, communication should resume soon.

The parachute opened strictly according to schedule, but “Yantari” (this is the crew’s call sign) was still silent. The silence on the air began to get annoying. After the descent apparatus landed, rescuers and doctors almost immediately ran up to him. There was no response to the knock on the casing, so the hatch had to be opened in emergency mode.

appeared before my eyes terrible picture: Dobrovolsky, Patsayev and Volkov sat dead in their chairs. The tragedy shocked everyone with its inexplicability. After all, the landing went according to plan, and until recently the cosmonauts were in touch. Death occurred from an almost instantaneous air leak. However, what caused it was not yet known.

The special commission literally reconstructed in seconds what actually happened. It turned out that during landing the crew discovered an air leak through the ventilation valve above the commander's seat.

They had no time left to close it: this required 55 seconds for a healthy person, and there were no spacesuits or even oxygen masks in the equipment.

The medical commission found everyone traces of the dead cerebral hemorrhage and damage to the eardrums. The air dissolved in the blood literally boiled and clogged the blood vessels, even entering the chambers of the heart.

For search technical malfunction, which caused valve depressurization, the commission conducted more than 1000 experiments with the involvement of the manufacturer. At the same time, the KGB was working on a variant of deliberate sabotage.

However, none of these versions have been confirmed. Elementary negligence at work played a role here. Checking the condition of the Soyuz, it turned out that many of the nuts were simply not tightened properly, which led to the failure of the valve.

The day after the tragedy, all USSR newspapers were published with black mourning frames, and all space flights were stopped for 28 months. Now the mandatory equipment for cosmonauts included spacesuits, but at the cost of this was the lives of three pilots who never saw the bright summer sun on their native Earth.