On July 6, 1796, Emperor Nicholas I was born, distinguished by his love of law, justice and order. One of his first steps after the coronation was the return of Alexander Pushkin from exile.

Today we will plunge into the reign of Nicholas I and tell you a little about what remains of him on the pages of history.

Despite the fact that attempts on the life of the tsar, according to the laws that existed at that time, were punishable by quartering, Nicholas I replaced this execution with hanging. Some contemporaries wrote about his despotism. At the same time, historians note that the execution of five Decembrists was the only one in the entire 30 years of the reign of Nicholas I. For comparison, for example, under Peter I and Catherine II, executions numbered in the thousands, and under Alexander II - in the hundreds. It is also noted that under Nicholas I, torture was not used against political prisoners.

After the coronation, Nicholas I ordered the return of Pushkin from exile

The most important direction domestic policy became the centralization of power. To carry out the tasks of political investigation, a permanent body was created in July 1826 - the Third Department of the Personal Chancellery - secret service, who had significant powers. The first of the secret committees was also created, whose task was, firstly, to consider the papers sealed in the office of Alexander I after his death, and, secondly, to consider the issue of possible transformations of the state apparatus.

Some authors call Nicholas I a “knight of autocracy”: he firmly defended its foundations and suppressed attempts to change the existing system, despite the revolutions in Europe. After the suppression of the Decembrist uprising, he launched large-scale measures in the country to eradicate the “revolutionary infection”.

Nicholas I focused on discipline within the army, since at that time there was licentiousness in it. Yes, he emphasized it so much that the minister during the reign of Alexander II wrote in his notes: “Even in military matters, which the emperor was engaged in with such passionate enthusiasm, the same concern for order and discipline prevailed; they were not chasing the essential improvement of the army, not the adaptation of it to a military purpose, but behind only external harmony, behind a brilliant appearance at parades, pedantic observance of countless petty formalities that dull human reason and kill the true military spirit.”

During the reign of Nicholas I, meetings of commissions were held to alleviate the situation of serfs. Thus, a ban was introduced on exiling peasants to hard labor, selling them individually and without land, and peasants received the right to redeem themselves from the estates being sold. A reform of state village management was carried out and a “decree on obligated peasants” was signed, which became the foundation for the abolition of serfdom.

Under Nicholas I, the Code of Laws of the Russian Empire appeared

One of Nikolai Pavlovich’s greatest achievements can be considered the codification of law. Mikhail Speransky, attracted by the tsar to this work, performed a titanic work, thanks to which the Code of Laws of the Russian Empire appeared.

The state of affairs in industry at the beginning of the reign of Nicholas I was the worst in the entire history of the Russian Empire. By the end of the reign of Nicholas I the situation had changed greatly. For the first time in the history of the Russian Empire, a technically advanced and competitive industry began to form in the country. Its rapid development led to a sharp increase in the urban population.

Nicholas I introduced a reward system for officials and controlled it himself

For the first time in the history of Russia, under Nicholas I, intensive construction of paved roads began.

He introduced a moderate system of incentives for officials, which he controlled to a large extent. Unlike previous reigns, historians have not recorded large gifts in the form of palaces or thousands of serfs granted to any nobleman or royal relative.

An important aspect of foreign policy was the return to principles Holy Alliance. Russia's role in the fight against any manifestations of the “spirit of change” in European life has increased. It was during the reign of Nicholas I that Russia received the unflattering nickname of “the gendarme of Europe.”

Russian-Austrian relations were hopelessly damaged until the end of the existence of both monarchies.

During the reign of Nicholas I, Russia was called the gendarme of Europe

Russia under Nicholas I abandoned plans for partition Ottoman Empire, which were discussed under previous emperors (Catherine II and Paul I), and began to pursue a completely different policy in the Balkans - a policy of protecting the Orthodox population and ensuring its religious and civil rights, up to political independence.

Russia under Nicholas I abandoned plans to divide the Ottoman Empire

During the reign of Nicholas I, Russia participated in the following wars: Caucasian War 1817-1864, Russian-Persian War 1826-1828, Russian-Turkish War 1828-1829, Crimean War 1853—1856.

As a result of the defeat of the Russian army in Crimea in 1855, at the beginning of 1856 the Paris Peace Treaty was signed, under the terms of which Russia was prohibited from having naval forces, arsenals and fortresses. Russia became vulnerable from the sea and lost the opportunity to conduct an active foreign policy in this region. Also in 1857, a liberal customs tariff was introduced in Russia. The result was an industrial crisis: by 1862, iron smelting in the country fell by a quarter, and cotton processing by 3.5 times. The increase in imports led to the outflow of money from the country, a deterioration in the trade balance and a chronic shortage of money in the treasury.

The future Emperor Nicholas I, the third son of Emperor Paul I and Empress Maria Feodorovna, was born on July 6 (June 25, old style) 1796 in Tsarskoye Selo (Pushkin).

As a child, Nikolai was very fond of military toys, and in 1799, for the first time, he put on the military uniform of the Life Guards Cavalry Regiment, of which he had been the chief since infancy. According to the traditions of that time, Nikolai began serving at the age of six months, when he received the rank of colonel. He was prepared, first of all, for a military career.

Baroness Charlotte Karlovna von Lieven was involved in the upbringing of Nicholas; from 1801, General Lamzdorf was entrusted with the supervision of Nicholas's upbringing. Other teachers included the economist Storch, the historian Adelung, and the lawyer Balugyansky, who failed to interest Nikolai in their subjects. He was good at engineering and fortification. Nicholas's education was limited mainly to military sciences.

Nevertheless, from a young age the emperor drew well, had good artistic taste, loved music very much, played the flute well, and was a keen connoisseur of opera and ballet.

Having married on July 1, 1817, the daughter of the Prussian king Frederick William III, the German princess Friederike-Louise-Charlotte-Wilhelmina, who converted to Orthodoxy and became Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duke lived happy family life without taking part in government affairs. Before his accession to the throne, he commanded a guards division and served (since 1817) as inspector general for engineering. Already in this rank, he showed great concern for military educational institutions: on his initiative, company and battalion schools were established in the engineering troops, and in 1819 the Main Engineering School was established (now Nikolaevskaya engineering academy); The “School of Guards Ensigns” (now the Nikolaev Cavalry School) owes its existence to his initiative.

His excellent memory, which helped him recognize the face and remember even ordinary soldiers by name, gained him great popularity in the army. The emperor was distinguished by considerable personal courage. When a cholera riot broke out in the capital, on June 23, 1831, he rode out in a carriage to a crowd of five thousand gathered on Sennaya Square and stopped the riots. He also stopped unrest in the Novgorod military settlements, caused by the same cholera. The Emperor showed extraordinary courage and determination during the fire of the Winter Palace on December 17, 1837.

The idol of Nicholas I was Peter I. Extremely unpretentious in everyday life, Nicholas, already an emperor, slept on a hard camp bed, covered with an ordinary overcoat, observed moderation in food, preferring the simplest food, and almost did not drink alcohol. He was very disciplined and worked 18 hours a day.

Under Nicholas I, the centralization of the bureaucratic apparatus was strengthened, a set of laws of the Russian Empire was compiled, and new censorship regulations were introduced (1826 and 1828). In 1837, traffic was opened on the first Tsarskoye Selo railway in Russia. The Polish uprising of 1830-1831 and the Hungarian revolution of 1848-1849 were suppressed.

During the reign of Nicholas I, the Narva Gate, the Trinity (Izmailovsky) Cathedral, the Senate and Synod buildings, the Alexandria Column, the Mikhailovsky Theater, the building Assembly of the Nobility, New Hermitage, Anichkov Bridge, Blagoveshchensky Bridge across the Neva (Lieutenant Schmidt Bridge) were reconstructed, end pavement was laid on Nevsky Prospekt.

An important aspect of Nicholas I's foreign policy was a return to the principles of the Holy Alliance. The Emperor sought a favorable regime for Russia in the Black Sea straits; in 1829, peace was concluded in Andrianople, according to which Russia received the eastern shore of the Black Sea. During the reign of Nicholas I, Russia took part in the Caucasian War of 1817-1864, the Russian-Persian War of 1826-1828, Russian-Turkish war 1828-1829, Crimean War 1853-1856.

Nicholas I died on March 2 (February 18, Old Style) 1855, according to the official version - from a cold. He was buried in the Cathedral of the Peter and Paul Fortress.

The emperor had seven children: Emperor Alexander II; Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, married Duchess of Leuchtenberg; Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, married Queen of Württemberg; Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna, wife of Prince Frederick of Hesse-Kassel; Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich; Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich; Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich.

The material was prepared based on information from open sources

As you know, Nicholas I died on February 18 (March 2), 1855. It was officially announced that the emperor caught a cold while taking part in the parade in a light uniform and died of pneumonia (pneumonia). As usually happens, in the very first days after the death of Nicholas, legends arose about his sudden death, and they began to spread with lightning speed. The first version is that the tsar could not survive the defeat in the Crimean War and committed suicide. The second is that physician Martin Mandt poisoned the emperor. What really happened?

Emperor Nicholas I

“Completely unexpected even for St. Petersburg”

Poet, journalist and (which is very important!) Doctor of Medical Sciences V.L. Paykov is already in Soviet era reasoned on this matter: “Rumors about suicide, about an artificially induced cold, about taking poison when the cold began to go away, etc., came from the palace, from the medical world, spread among the literary public, and wandered among the philistines<…>Such a physically strong person as Nicholas I was could not die from a cold, even its severe form.”

And here the question involuntarily arises: were there any serious reasons for denying the official version of the emperor’s death? The answer to this question is obvious: of course they were.

First of all, as historian E.V. writes. Tarle, Russians and foreigners who knew Nicholas’s nature always said that they could not imagine the emperor “sitting down as a loser at the diplomatic green table for negotiations with the victors.” This is where the version comes from that Nicholas I took the news of the defeat of the Russian troops near Evpatoria hard. He allegedly realized that this was a harbinger of defeat in the entire Crimean War, and therefore asked Martin Mandt to give him poison, which would allow him to die, protecting himself from shame.

Supporters of another version - the doctor's fellow contemporaries - unanimously accused him of underestimating the condition of his crowned patient and of inadequacy of treatment methods.

The writing fraternity also played a role. She preferred the suicide version.

As Tarle noted, rumors of suicide “were widespread in Russia and Europe (and had an impact on minds),” and “sometimes these rumors were believed by people who were not at all guilty of gullibility and frivolity.” For example, publicist N.V. Shelgunov and historian N.K. Schilder.

In particular, Schilder succinctly stated: “I was poisoned.” But Shelgunov gave us this version of the rumors about the “highest” death: “Emperor Nicholas died completely unexpectedly even for St. Petersburg, which had never heard anything about his illness before. It is clear that the sudden death of the sovereign caused speculation. By the way, they said that the dying emperor ordered to call his grandson, the future crown prince. The Emperor lay in his office, on a camp bed, under soldier's overcoat. When the Tsarevich entered, the Emperor allegedly said to him: “Learn to die,” and these were his last words. But there was other news. It was said that Emperor Nicholas, shocked by the failures of the Crimean War, felt unwell and then caught a severe cold. Despite his illness, he ordered a review of the troops. On the day of the parade, a sudden frost hit, but the sick sovereign did not find it convenient to postpone the parade. When the riding horse was brought up, the physician Mandt grabbed him by the bit and, wanting to warn the emperor about the danger, allegedly said: “Sire, what are you doing? This is worse than death: it is suicide,” but Emperor Nicholas, without answering anything, mounted his horse and gave him spurs.” It turns out that the form of voluntary death of Nicholas I was not poison, but an artificially induced cold.

Naturally, there were immediately those who considered all the rumors about the Tsar’s suicide to be without any basis. For example, in 1855 a book by Count D.N. was published. Bludov "The last hours of the life of Emperor Nicholas I." So there it is said about the death of the king: “This precious life was put to an end by a cold, which at first seemed insignificant, but, unfortunately, was combined with other causes of disorder, which had long been hidden in a constitution that was only [outwardly] strong, but in fact shocked , even exhausted by the labors of extraordinary activity, worries and sorrows..."

"Iron" health of the emperor

Surprisingly, many contemporaries considered the emperor’s health “iron.” In reality, it was not so heroic. Nikolai Pavlovich was an ordinary person, and the impression of the indestructibility of his health was rather the result of his conscious efforts to shape the appearance of “the master of a huge empire.” In fact, as Tarle notes, “that something was wrong with the sovereign recently was clear to absolutely everyone who had access to the court.”

However, the emperor’s health deteriorated much earlier than “everyone” noticed it. In December 1837, a terrible fire engulfed the Winter Palace. This fire lasted about thirty hours. As a result, the second and third floors of the palace were completely burned out and many valuable works of art were lost forever. This event left an indelible mark on the psyche of Nicholas I: every time he saw fire or smelled smoke, he turned pale, felt dizzy and his heartbeat quickened.

Historians generally believe that Nicholas I’s health problems began in 1843. While traveling across Russia, on the road from Penza to Tambov, his carriage overturned, and the Tsar broke his collarbone. From that time on, Nikolai Pavlovich’s health began to noticeably change, and most importantly, he developed nervous irritability.

But the emperor felt especially bad in 1844–1845. His “legs hurt and were swollen”; doctors were afraid that he would develop dropsy. He even went to Italy, to Palermo, for treatment. And in the spring of 1847, Nikolai Pavlovich’s dizziness intensified. The longer he ruled the country, the gloomier he looked at the future of Russia, the fate of Europe, and even his personal life. He experienced the death of many figures of his reign very hard - Prince A.N. Golitsyna, M.M. Speransky, A.Kh. Benckendorf. Death of daughter Alexandra in 1844 and tragic events French Revolution The year 1848 also clearly did not improve his health.

In January 1854, the emperor began to complain of pain in his foot. The then head of the gendarmerie L.V. Dubelt wrote about this: “Mandt says that he has erysipelas, while others claim that it is gout.” V.L. Paykov already clarified in Soviet times: “In recent years“In my life, gout attacks became more frequent against the background of the appearance of obesity, which, apparently, was associated with a violation of the diet.” One might think that the Soviet researcher stood behind the emperor’s eating chair every day.

A. Kozlov. News from Sevastopol. Lithography. 1854–1855

Painful blow

Of course, the Crimean campaign dealt a strong blow to Nicholas I. Relatives often saw the tsar in his office “crying like a child when he received every bad news.” “Still, one should not exaggerate the significance of unfavorable news about what happened near Yevpatoria,” believed historian P.K. Solovyov. – Hoping for the best, the king was preparing for the worst. In letters dated early February 1855, Nicholas I indicated to Adjutant General M.D. Gorchakov and Field Marshal I.F. Paskevich on the possibility of “failure in Crimea”, on the need to prepare the defense of Nikolaev and Kherson. He considered the likelihood of Austria entering the war to be very high and gave orders regarding possible military operations in the Kingdom of Poland and Galicia. The tsar did not have any special illusions regarding the neutrality of Prussia.”

He realized long ago: the leading European powers have never loved and will never love Russia. Of course, a lot of explanations can be found for this Russophobia of theirs: France, beaten by the Russians in 1812–1814, dreamed of revenge. Already in 1815, she concluded a secret “defensive alliance” with England and Austria, directed against Russia. Another problem was the so-called “Eastern question”, that is, the security of Russia’s southern borders and the strengthening of its positions in the Balkans. Russia's patronage of the Orthodox population of the Balkan Peninsula interfered with the expansionist machinations of England and Austria. In addition, England, which saw Russia as its main geopolitical enemy, was concerned about the successes of the Russians in the Caucasus and feared their possible advance into Central Asia, which it had its own plans for. As for Prussia, it, like Austria, was ready to support any action directed against Russia. By the middle of the 19th century, Nicholas I found himself in diplomatic isolation, and this could not help but sadden him.

W. Simpson. Landing in Evpatoria. It took place on September 2 (14), 1854. They reported to Nikolai:

coalition expeditionary force transported 61 thousand soldiers to Crimea

Yes, the failure to storm Yevpatoria dealt a painful blow to Nikolai Pavlovich’s pride, but it was not the event that predetermined the outcome of the entire war. The fate of the campaign depended on the defenders of Sevastopol, who continued to fight until the end of August 1855. So the defeat at Evpatoria could not push the emperor to commit suicide.

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna testified: “It was not in his character to complain.” He constantly repeated: “I must serve everything in order. And if I become decrepit, then I’ll go into pure retirement. If I’m not fit to serve, I’ll leave, but as long as I have the strength, I’ll try until the end. I will bear my cross as long as I have enough strength.”

So the historian Paykov rightly believed that “one should not forget the important circumstance that Nicholas I was a military man to the core, who knew full well that wars bring with them not only losses, but also defeats. And you must be able to accept defeats with dignity. And on their basis to build the building of future victory. The character of this man, strong, decisive, purposeful, the entire history of his thirty-year reign does not give the slightest reason to assume suicide on his part due to private military failures.”

However, many of the emperor's sentimental contemporaries could not come to terms with the prosaic picture of his death. Here is Prince V.P. Meshchersky romantically asserted: “Nikolai Pavlovich was dying of grief, and precisely from Russian grief. This dying had no signs of physical illness - it came only at the last minute - but the dying took place in the form of an undoubted predominance of mental suffering over his physical being.

The last days of Nicholas I

Director of His Majesty's Office, poet V.I. Panaev testified that no matter how hard Nikolai Pavlovich tried “to overcome himself, to hide his inner torment, it began to be revealed by the gloominess of his gaze, pallor, even some kind of darkening of his beautiful face and the thinness of his whole body. Given his state of health, the slightest cold could develop a dangerous disease in him. And so it happened. Not wanting to refuse Count Kleinmichel (P.A. Kleinmichel was the Minister of Railways, who oversaw the construction of the Nikolaev Railway. - Author) in the request to be seated by his father with his daughter, the sovereign went to the wedding, despite the severe frost, wearing a red Horse Guards uniform with elk trousers and silk stockings. That evening was the beginning of his illness: he caught a cold...

Neither in the city, nor even at court did they pay attention to the sovereign’s illness; They said he was unwell, but he was not lying down. The Emperor did not express concerns about his health, either because he really did not suspect any danger, or, more likely, in order not to disturb his kind subjects. To this day last reason he forbade the publication of bulletins about his illness.”

He was sick for five days, but then he got stronger and went to the Mikhailovsky Manege to review the troops. Upon returning, I felt unwell: the cough and shortness of breath resumed. But the next day the emperor again went to Manege to inspect the marching battalions of the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments. On February 11, he could no longer get out of bed. And on the 12th I received a telegram about the defeat of Russian troops near Yevpatoria. “How many lives have been sacrificed for nothing,” Nikolai Pavlovich repeated these words in last days many times in your life.

Near Yevpatoria, on February 5 (17), 1855, 168 Russian soldiers and officers were killed, 583 people were wounded (including one general), and another 18 people were missing.

On the night of February 17-18, the emperor became noticeably worse. He began to experience paralysis. What caused it? This remains a mystery. If we assume that he did commit suicide, then who exactly gave him the poison? It is known that two physicians were at the patient’s bedside: Martin Mandt and Philippe Carell. In memoirs and historical literature they usually point to Dr. Mandt. But, for example, Colonel I.F. Savitsky, the adjutant of Tsarevich Alexander, argued: “The German Mandt, a homeopath, the tsar’s beloved physician, whom popular rumor accused of the death (poisoning) of the emperor, was forced to flee abroad, told me about the last minutes of the great ruler: “After receiving the dispatch about the defeat at Evpatoria, Nicholas I called me to him and said: “You have always been loyal to me, and therefore I want to talk to you confidentially - the course of the war revealed the fallacy of my entire foreign policy, but I have neither the strength nor the desire to change and go differently dear, that would go against my beliefs. Let my son, after my death, make this turn. I am unable and must leave the stage, so I called you to ask you to help me. Give me poison that would allow me to give up my life without unnecessary suffering, quickly enough, but not suddenly (so as not to cause misunderstandings).”

However, according to Savitsky's memoirs, Mandt refused to give the emperor poison. But on the same night, February 18 (March 2), 1855, the emperor died.

And by morning, rapid decomposition of the body began, and yellow, blue and purple spots appeared on the face of the deceased. The heir to the throne, Alexander, was horrified to see his father so disfigured, and called two doctors: N.F. Zdecauer and I.I. Myanovsky - professors of the Medical-Surgical Academy. He ordered them to use any means necessary to remove “all signs of poisoning in order to present the body in proper form four days later for a public farewell according to tradition and protocol.”

“He was too much of a believer to give in to despondency.”

Supporters of the poisoning version claim that the two summoned professors, in order to hide the real cause of death, literally repainted the face of the deceased and properly processed it. But allegedly used by them new way Embalming the body was not yet well developed, and it did not prevent its rapid decomposition. But at the same time, it is somehow forgotten that Zdekauer and Mianowski were therapists and never practiced embalming at all!

It is also alleged that the last will of Nicholas I was a ban on the autopsy of his body: allegedly he feared that the autopsy would reveal the secret of his death, which the desperate emperor wanted to take with him to the grave. But this is not entirely true. Nikolai Pavlovich wrote his last spiritual will on May 4, 1844. And in this document there is no mention of the ritual according to which he would be buried in the event of his death. However, back in 1828, during the funeral of his mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, he publicly stated that during his burial the ceremony should be simplified as much as possible.

V.L. In this regard, Paykov writes: “When Nicholas I died, the “simplified ceremony” of the funeral was interpreted as a desire to quickly hide the body of the deceased in the grave, and with it the secret of his “mysterious” death. But it was just about Nicholas I’s desire to save public funds on his funeral.”

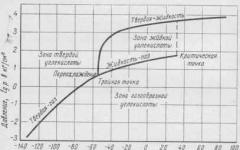

As for the rapid decomposition of the body of the deceased, it could be due to the fact that there were no special refrigeration chambers at that time. But the air temperature in St. Petersburg that day suddenly rose sharply from -20°C to +2°C. Plus, as noted by the maid of honor A.F. Tyutchev, “the farewell to the emperor took place in a small room, where many people gathered who wanted to say goodbye to the king, and the heat was almost unbearable.”

So the rumors about the king’s suicide are unfounded.

And two more important points.

Firstly, Nicholas I was a deeply religious man who cared about the posthumous fate of his soul. His daughter, Olga Nikolaevna, said: “He was too much of a believer to give in to despondency.” And even more so, he hardly even allowed the thought of suicide.

But here is the testimony of the Emperor’s aide-de-camp V.I. Dena: “Whoever knew Nikolai Pavlovich closely could not help but appreciate the deeply religious feeling that distinguished him and which, of course, would have helped him with Christian humility to endure all the blows of fate, no matter how severe, no matter how sensitive to his pride they were.” .

Any Christian knows that unauthorized death is a grave offense, a mortal sin, surpassing even murder. Suicide is the only one of the most terrible sins that cannot be repented of. So the 58-year-old emperor clearly would not dare to go beyond this, challenging God himself and refusing to recognize Him as the boss of human life.

Secondly, speaking about the death of Nicholas I, we must not forget about one more circumstance. The Emperor was on the verge of old age - in July 1855 he would have turned 59 years old. Of course, in modern times this is not much. But in comparison with other Pavlovichs, Nikolai was almost a long-liver. For comparison: his elder brother Alexander I died at the age of 47, Konstantin Pavlovich - at 52, Mikhail Pavlovich - at 51, Ekaterina Pavlovna - at 30.

Nicholas I was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

Alexandra Feodorovna, his wife, died on October 20 (November 1), 1860 in Tsarskoe Selo, and she was also buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

By the way

Historian Tarle notes: “For the enemies of the Nicholas regime, this alleged suicide was, as it were, a symbol of the complete failure of the entire system of merciless oppression, the personification of which was the tsar, and they wanted to believe that in the night hours of February 17-18, left alone with Mandt, the culprit who created this system and led Russia to military disaster, realized his historical crimes and pronounced a death sentence on himself and his regime. The broad masses in rumors of suicide drew evidence of the approaching collapse of the system, which so recently seemed indestructible.”

A symbol of failure... I realized... I pronounced a sentence on myself... All this, perhaps, is so. But from awareness to a concrete step there is an abyss. As they say, “it happens that you don’t want to live, but this does not mean at all that you want not to live.” And if so, then one cannot but agree with the historian P.A. Zayonchkovsky, who makes the following conclusion: “The events in Sevastopol sobered him up. However, rumors about the king’s suicide are without any basis.”

Sergey Nechaev

The personality of Emperor Nicholas I is very controversial. Thirty years of rule are a series of paradoxical phenomena:

- unprecedented cultural flourishing and manic censorship;

- total political control and prosperity of corruption;

- the rise of industrial production and economic backwardness from European countries;

- control over the army and its powerlessness.

Statements from contemporaries and real ones historical facts also cause a lot of controversy, so it is difficult to objectively assess

Childhood of Nicholas I

Nikolai Pavlovich was born on June 25, 1796 and became the third son of the imperial Romanov couple. Very little Nikolai was raised by Baroness Charlotte Karlovna von Lieven, to whom he became very attached and adopted from her some character traits, such as strength of character, perseverance, heroism, and openness. It was then that his passion for military affairs already manifested itself. Nikolai loved watching military parades, divorces, and playing with military toys. And already at the age of three he put on his first military uniform of the Life Guards Horse Regiment.

He suffered his very first shock at the age of four, when his father, Emperor Pavel Petrovich, died. Since then, the responsibility of raising the heirs fell on the shoulders of the widow Maria Feodorovna.

Mentor of Nikolai Pavlovich

Lieutenant General Matvey Ivanovich Lamzdorf, former director of the gentry (first) was appointed Nikolai's mentor from 1801 and over the next seventeen years. cadet corps under Emperor Paul. Lamzdorf did not have the slightest idea about the methods of educating royalty - future rulers - and about any educational activities in general. His appointment was justified by the desire of Empress Maria Feodorovna to protect her sons from getting carried away with military affairs, and this was main goal Lamsdorf. But instead of interesting the princes in other activities, he went against all their wishes. For example, accompanying the young princes on their trip to France in 1814, where they were eager to participate in military operations against Napoleon, Lamzdorf deliberately drove them very slowly, and the princes arrived in Paris when the battle was already over. Due to incorrectly chosen tactics, Lamzdorf’s educational activities did not achieve their goal. When Nicholas I got married, Lamzdorf was relieved of his duties as a mentor.

Hobbies

The Grand Duke diligently and passionately studied all the wisdom military science. In 1812, he was eager to go to war with Napoleon, but his mother did not let him. In addition, the future emperor was interested in engineering, fortification, and architecture. But humanities Nikolai did not like and was careless about their study. Subsequently, he greatly regretted this and even tried to fill in the gaps in his training. But he never managed to do this.

Nikolai Pavlovich was fond of painting, played the flute, and loved opera and ballet. He had good artistic taste.

The future emperor had a beautiful appearance. Nicholas 1 is 205 cm tall, thin, broad-shouldered. The face is slightly elongated, the eyes are blue, and there is always a stern look. Nikolai had excellent physical training and good health.

Marriage

The elder brother Alexander I, having visited Silesia in 1813, chose a bride for Nicholas - the daughter of the King of Prussia, Charlotte. This marriage was supposed to strengthen Russian-Prussian relations in the fight against Napoleon, but unexpectedly for everyone, the young people sincerely fell in love with each other. On July 1, 1817 they got married. Charlotte of Prussia in Orthodoxy became Alexandra Feodorovna. The marriage turned out to be happy and had many children. The Empress bore Nicholas seven children.

After the wedding, Nicholas 1, biography and interesting facts which is presented to your attention in the article, began to command a guards division, and also took up the duties of inspector general for engineering.

While doing what he loved, the Grand Duke took his responsibilities very seriously. He opened company and battalion schools under the engineering troops. In 1819, the Main Engineering School (now the Nikolaev Engineering Academy) was founded. Thanks to his excellent memory for faces, which allows him to remember even ordinary soldiers, Nikolai won respect in the army.

Death of Alexander 1

In 1820, Alexander announced to Nicholas and his wife that Konstantin Pavlovich, the next heir to the throne, intended to renounce his right due to childlessness, divorce and remarriage, and Nicholas should become the next emperor. In this regard, Alexander signed a manifesto approving the abdication of Konstantin Pavlovich and the appointment of Nikolai Pavlovich as heir to the throne. Alexander, as if sensing his imminent death, bequeathed the document to be read out immediately after his death. On November 19, 1825, Alexander I died. Nicholas, despite the manifesto, was the first to swear allegiance to Prince Constantine. It was a very noble and honest act. After some period of uncertainty, when Constantine did not officially abdicate the throne, but also refused to take the oath. The growth of Nicholas 1 was rapid. He decided to become the next emperor.

Bloody start to reign

On December 14, on the day of the oath of Nicholas I, an uprising was organized (called the Decembrist uprising), aimed at overthrowing the autocracy. The uprising was suppressed, the surviving participants were sent into exile, and five were executed. The emperor's first impulse was to have mercy on everyone, but fear palace coup forced to organize a trial to the fullest extent of the law. And yet Nikolai acted generously with those who wanted to kill him and his entire family. There are even confirmed facts that the wives of the Decembrists received monetary compensation, and children born in Siberia could study in the best educational institutions at the expense of the state.

This event influenced the course of the further reign of Nicholas 1. All his activities were aimed at preserving autocracy.

Domestic policy

The reign of Nicholas 1 began when he was 29 years old. Accuracy and exactingness, responsibility, struggle for justice, combined with high efficiency were the striking qualities of the emperor. His character was influenced by years of army life. He led a rather ascetic lifestyle: he slept on a hard bed, covered with an overcoat, observed moderation in food, did not drink alcohol and did not smoke. Nikolai worked 18 hours a day. He was very demanding, first of all, of himself. He considered the preservation of autocracy his duty, and all his political activities served this goal.

Russia under Nicholas 1 underwent the following changes:

- Centralization of power and creation of a bureaucratic management apparatus. The emperor only wanted order, control and accountability, but in essence it turned out that the number of official posts increased significantly and along with them the number and size of bribes increased. Nikolai himself understood this and told his eldest son that in Russia only the two of them did not steal.

- The solution to the issue of serfs. Thanks to a series of reforms, the number of serfs decreased significantly (from 58% to 35% over approximately 45 years), and they acquired rights, the protection of which was controlled by the state. The complete abolition of serfdom did not occur, but the reform served as a starting point in this matter. Also at this time, an education system for peasants began to take shape.

- The emperor paid special attention to order in the army. Contemporaries criticized him for paying too close attention to the troops, while he was of little interest to the morale of the army. Frequent checks, inspections, and punishments for the slightest mistakes distracted soldiers from their main tasks and made them weak. But was it really so? During the reign of Emperor Nicholas 1, Russia fought with Persia and Turkey in 1826-1829, and in Crimea in 1853-1856. Russia won the wars with Persia and Turkey. The Crimean War led to Russia's loss of influence in the Balkans. But historians cite the reason for the defeat of the Russians as the economic backwardness of Russia compared to the enemy, including the existence of serfdom. But a comparison of human losses in the Crimean War with other similar wars shows that they are less. This proves that the army under the leadership of Nicholas I was powerful and highly organized.

Economic development

Emperor Nicholas 1 inherited a Russia deprived of industry. All production items were imported. By the end of the reign of Nicholas 1, economic growth was noticeable. Many types of production necessary for the country already existed in Russia. Under his leadership, the construction of paved roads and railways began. In connection with the development railway transport The machine-building industry, including car-building, began to develop. An interesting fact is that Nicholas I decided to build railways wider (1524 mm) than in European countries (1435 mm), in order to make it difficult for the enemy to move around the country in case of war. And it was very wise. It was this trick that prevented the Germans from supplying full ammunition during their attack on Moscow in 1941.

In connection with growing industrialization, intensive urban growth began. During the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, the urban population more than doubled. Thanks to engineering education received in his youth, Nikolai 1 Romanov oversaw the construction of all major facilities in St. Petersburg. His idea was not to exceed the height of the cornice Winter Palace for all city buildings. As a result, St. Petersburg became one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

Under Nicholas 1, growth in the educational sphere was also noticeable. A lot was open educational institutions. Among them are the famous Kyiv University and St. Petersburg technological institute, military and naval academies, a number of schools, etc.

The rise of culture

The 19th century was a real heyday literary creativity. Pushkin and Lermontov, Tyutchev, Ostrovsky, Turgenev, Derzhavin and other writers and poets of this era were incredibly talented. At the same time, Nicholas 1 Romanov introduced the most severe censorship, reaching the point of absurdity. Therefore, literary geniuses periodically experienced persecution.

Foreign policy

Foreign policy during the reign of Nicholas I included two main directions:

- Return to the principles of the Holy Alliance, suppression of revolutions and any revolutionary ideas in Europe.

- Strengthening influence in the Balkans for free navigation in and Bosporus.

These factors became the cause of the Russian-Turkish, Russian-Persian and Crimean wars. The defeat in the Crimean War led to the loss of all previously won positions in the Black Sea and the Balkans and provoked an industrial crisis in Russia.

Death of the Emperor

Nicholas 1 died on March 2, 1855 (58 years old) from pneumonia. He was buried in the Cathedral of the Peter and Paul Fortress.

And finally...

The reign of Nicholas I undoubtedly left a tangible mark on both the economy and cultural life of Russia, however, it did not lead to any epochal changes in the country. The following factors forced the emperor to slow down progress and follow the conservative principles of autocracy:

- moral unpreparedness to govern the country;

- lack of education;

- fear of overthrow due to the events of December 14;

- feeling of loneliness (conspiracies against father Paul, brother Alexander, abdication of brother Constantine).

Therefore, none of the subjects regretted the death of the emperor. Contemporaries more often condemned personal characteristics Nicholas 1, he was criticized as a politician and as a person, but historical facts speak of the emperor as a noble man who completely devoted himself to serving Russia.