Crimea was like a long-awaited reward for those who, moving from the depths of Russia, managed to overcome the steppes scorched by the heat. Steppes, mountains and subtropics of the South Coast - such natural conditions are not found anywhere else in Russia. However, in the world too...

The ethnic history of Crimea is also unusual and unique. Crimea was populated primitive people thousands of years ago, and throughout its history it has constantly accepted new settlers. But since on this small peninsula there are mountains that more or less could protect the inhabitants of Crimea, and there is also a sea from which new settlers, goods and ideas could arrive, and coastal cities could also provide protection to the Crimeans, it is not surprising that Some historical ethnic groups were able to survive here. Mixings of peoples have always taken place here, and it is no coincidence that historians talk about the “Tavro-Scythians” and “Goto-Alans” living here.

In 1783, Crimea (along with a small territory outside the peninsula) became part of Russia. By this time, there were 1,474 settlements in Crimea, most of them very small. Moreover, most Crimean settlements were multinational. But since 1783, the ethnic history of Crimea has changed radically.

Crimean Greeks

The first Greek settlers arrived on the land of Crimea 27 centuries ago. And it was in Crimea that the small Greek ethnic group, the only one of all Greek ethnic groups outside Greece, managed to survive. Actually, two Greek ethnic groups lived in Crimea - the Crimean Greeks and the descendants of the “real” Greeks from Greece who moved to Crimea at the end of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Of course, the Crimean Greeks, in addition to the descendants of ancient colonists, absorbed many ethnic elements. Under the influence and charm of Greek culture, many Tauris became Hellenized. Thus, the tombstone of a certain Tikhon, originally from Taurus, dating back to the 5th century BC, has been preserved. Many Scythians also Hellenized. In particular, some royal dynasties in the Bosporan kingdom were clearly of Scythian origin. The Goths and Alans experienced the strongest cultural influence of the Greeks.

Already from the 1st century, Christianity began to spread in Taurida, finding many adherents. Christianity was adopted not only by the Greeks, but also by the descendants of the Scythians, Goths and Alans. Already in 325, at the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea, Cadmus, Bishop of Bosporus, and Theophilus, Bishop of Gothia, were present. In the future, it was Orthodox Christianity that would unite the diverse population of Crimea into a single ethnic group.

The Byzantine Greeks and the Orthodox Greek-speaking population of Crimea called themselves “Romeans” (literally Romans), emphasizing their belonging to the official religion Byzantine Empire. As you know, the Byzantine Greeks called themselves Romans for several centuries after the fall of Byzantium. Only in the 19th century, under the influence of Western European travelers, did the Greeks in Greece return to the self-name “Hellenes”. Outside Greece, the ethnonym "Romei" (or, in Turkish pronunciation, "Urum") persisted until the twentieth century. In our time, the name “Pontic” (Black Sea) Greeks (or “Ponti”) has been established for all the various Greek ethnic groups in the Crimea and throughout New Russia.

The Goths and Alans who lived in the southwestern part of Crimea, which was called the “country of Dori,” although they retained their languages in everyday life for many centuries, their written language remained Greek. A common religion, a similar way of life and culture, and the spread of the Greek language led to the fact that over time the Goths and Alans, as well as the Orthodox descendants of the “Tavro-Scythians,” joined the Crimean Greeks. Of course, this did not happen right away. Back in the 13th century, Bishop Theodore and the Western missionary G. Rubruk met Alans in Crimea. Apparently, only to XVI century The Alans finally merged with the Greeks and Tatars.

Around the same time, the Crimean Goths disappeared. Since the 9th century, the Goths ceased to be mentioned in historical documents. However, the Goths still continued to exist as a small Orthodox ethnic group. In 1253, Rubruk, along with the Alans, also met the Goths in Crimea, who lived in fortified castles and whose language was Germanic. Rubruk himself, who was of Flemish origin, could, of course, distinguish Germanic languages from others. The Goths remained faithful to Orthodoxy, as Pope John XXII wrote with regret in 1333.

It is interesting that the first hierarch of the Orthodox Church of Crimea was officially called Metropolitan of Goth (in Church Slavonic - Gottheus) and Kafay (Kafina, that is, Feodosia).

It was probably the Hellenized Goths, Alans and other ethnic groups of Crimea that made up the population of the Principality of Theodoro, which existed until 1475. Probably, the Crimean Greeks also included fellow Russians from the former Tmutarakan principality.

However, from the end of the 15th and especially in the 16th century, after the fall of Theodoro, when the Crimean Tatars began to intensively convert their subjects to Islam, the Goths and Alans completely forgot their languages, switching partly to Greek, which was already familiar to them all, and partly to Tatar , which has become the prestigious language of the dominant people.

In the XIII-XV centuries, “Surozhans” were well known in Rus' - merchants from the city of Surozh (now Sudak). They brought special Sourozh goods to Rus' - silk products. It's interesting that even in " Explanatory dictionary living Great Russian language" by V.I. Dahl there are concepts that survived until the 19th century, such as "Surovsky" (i.e., Sourozh) goods, and the "Surozhsky series". Most of the Surozhan merchants were Greeks, some were Armenians and Italians, who lived under the rule of the Genoese in the cities of the southern coast of Crimea. Many of the Surozhans eventually moved to Moscow. The famous merchant dynasties of Moscow Rus' - the Khovrins, Salarevs, Troparevs, Shikhovs - came from the descendants of the Surozhans. Many of the descendants of Surozhans became rich in Moscow and influential people. The Khovrin family, whose ancestors came from the Mangup principality, even received boyarhood. The names of villages near Moscow - Khovrino, Salarevo, Sofrino, Troparevo - are associated with the merchant names of the descendants of the Surozhans.

But the Crimean Greeks themselves did not disappear, despite the emigration of Surozhans to Russia, the conversion of some of them to Islam (which turned converts into Tatars), as well as the increasingly increasing eastern influence in the cultural and linguistic spheres. In the Crimean Khanate, most of the farmers, fishermen, and winegrowers were Greeks.

The Greeks were an oppressed part of the population. Gradually, the Tatar language and oriental customs spread more and more among them. The clothing of the Crimean Greeks differed little from the clothing of Crimeans of any other origin and religion.

Gradually, an ethnic group of “Urums” (that is, “Romans” in Turkic) emerged in Crimea, denoting Turkic-speaking Greeks who retained the Orthodox faith and Greek identity. The Greeks, who retained the local dialect of the Greek language, retained the name “Romei”. They continued to speak 5 dialects of the local Greek language. By the end of the 18th century, Greeks lived in 80 villages in the mountains and on the southern coast, approximately 1/4 of the Greeks lived in the cities of the Khanate. About half of the Greeks spoke the Rat-Tatar language, the rest spoke local dialects, different from both the language of Ancient Hellas and spoken languages Greece proper.

In 1778, by order of Catherine II, in order to undermine the economy Crimean Khanate Christians living in Crimea - Greeks and Armenians - were evicted from the peninsula in the Azov region. As A.V. Suvorov, who carried out the resettlement, reported, only 18,395 Greeks left Crimea. The settlers founded the city of Mariupol and 18 villages on the shores of the Azov Sea. Some of the evicted Greeks subsequently returned to Crimea, but the majority remained in their new homeland on the northern shore of the Sea of Azov. Scientists usually called them Mariupol Greeks. Now it's Donetsk region Ukraine.

Today there are 77 thousand Crimean Greeks (according to the 2001 Ukrainian census), most of whom live in the Azov region. Many of them came out prominent figures Russian politics, culture and economy. Artist A. Kuindzhi, historian F. A. Hartakhai, scientist K. F. Chelpanov, philosopher and psychologist G. I. Chelpanov, art critic D. V. Ainalov, tractor driver P. N. Angelina, test pilot G. Ya. Bakhchivandzhi , polar explorer I. D. Papanin, politician, mayor of Moscow in 1991-92. G. Kh. Popov - all these are Mariupol (in the past - Crimean) Greeks. Thus, the history of the most ancient ethnic group in Europe continues.

"New" Crimean Greeks

Although a significant part of the Crimean Greeks left the peninsula, in Crimea already in 1774-75. new, “Greek” Greeks from Greece appeared. We are talking about those natives of the Greek islands in the Mediterranean Sea, who during the Russian- Turkish war 1768-74 helped the Russian fleet. After the end of the war, many of them moved to Russia. Of these, Potemkin formed the Balaklava battalion, which guarded the coast from Sevastopol to Feodosia with the center in Balaklava. Already in 1792, new Greek settlers numbered 1.8 thousand people. Soon the number of Greeks began to grow rapidly due to the widespread immigration of Greeks from the Ottoman Empire. Many Greeks settled in Crimea. At the same time, Greeks came from various regions of the Ottoman Empire, speaking different dialects, having their own characteristics of life and culture, differing from each other, and from the Balaklava Greeks, and from the “old” Crimean Greeks.

Balaklava Greeks fought bravely in the wars with the Turks and during the Crimean War. Many Greeks served in the Black Sea Fleet.

In particular, from among the Greek refugees came such outstanding military and political Russian figures as the Russian admirals of the Black Sea Fleet, the Alexiano brothers, the hero of the Russian-Turkish war of 1787-91. Admiral F.P. Lally, General A.I. Bella, who fell in 1812 near Smolensk, General Vlastov, one of the main heroes of the victory of Russian troops on the Berezina River, Count A.D. Kuruta, commander of Russian troops in Polish war 1830-31

In general, the Greeks served diligently, and it is no coincidence that there is an abundance of Greek surnames in the lists of Russian diplomacy, military and naval activities. Many Greeks were mayors, leaders of the nobility, and mayors. The Greeks were engaged in business and were abundantly represented in the business world of the southern provinces.

In 1859, the Balaklava battalion was abolished, and now most Greeks began to engage in peaceful activities - viticulture, tobacco growing, and fishing. The Greeks owned shops, hotels, taverns and coffee shops in all corners of Crimea.

After the establishment of Soviet power in Crimea, the Greeks experienced many social and cultural changes. In 1921, 23,868 Greeks lived in Crimea (3.3% of the population). At the same time, 65% of Greeks lived in cities. There were 47.2% of the total number of literate Greeks. In Crimea there were 5 Greek village councils, in which office work was conducted in Greek, there were 25 Greek schools with 1,500 students, and several Greek newspapers and magazines were published. At the end of the 30s, many Greeks became victims of repression.

The language problem of the Greeks was very complex. As already mentioned, some of the “old” Greeks of Crimea spoke the Crimean Tatar language (until the end of the 30s, there was even the term “Greco-Tatars” to designate them). The rest of the Greeks spoke various mutually incomprehensible dialects, far from modern literary Greek. It is clear that the Greeks, mainly urban residents, by the end of the 30s. switched to the Russian language, maintaining their ethnic identity.

In 1939, 20.6 thousand Greeks (1.8%) lived in Crimea. The decrease in their numbers is explained mainly by assimilation.

During the Great Patriotic War, many Greeks died at the hands of the Nazis and their accomplices from among Crimean Tatars. In particular, Tatar punitive forces destroyed the entire population of the Greek village of Laki. By the time of the liberation of Crimea, about 15 thousand Greeks remained there. However, despite the loyalty to the Motherland, which was demonstrated by the vast majority of Crimean Greeks, in May-June 1944 they were deported along with the Tatars and Armenians. A certain number of people of Greek origin, who were considered to be persons of another nationality according to their personal data, remained in Crimea, but it is clear that they tried to get rid of everything Greek.

After the removal of restrictions on the legal status of Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians and members of their families in special settlements, according to the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated March 27, 1956, the special settlers gained some freedom. But the same decree deprived them of the opportunity to receive back the confiscated property and the right to return to Crimea. All these years the Greeks were deprived of the opportunity to study the Greek language. Training took place in schools in Russian, which led to the loss native language among young people. Since 1956, Greeks have gradually returned to Crimea. Most of those who arrived were on native land separated from each other, and lived in separate families throughout Crimea. In 1989, 2,684 Greeks lived in Crimea. The total number of Greeks from Crimea and their descendants in the USSR was 20 thousand people.

In the 90s, the return of Greeks to Crimea continued. In 1994, there were already about 4 thousand of them. Despite their small numbers, Greeks actively participate in the economic, cultural and political life of Crimea, occupying a number of prominent positions in the administration of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, and engaging (with great success) in entrepreneurial activities.

Crimean Armenians

Another ethnic group has lived in Crimea for more than a millennium - the Armenians. One of the brightest and most original centers of Armenian culture has developed here. Armenians appeared on the peninsula a very long time ago. In any case, back in 711, a certain Armenian Vardan was declared the Byzantine emperor in Crimea. Mass immigration of Armenians to Crimea began in the 11th century, after the Seljuk Turks defeated the Armenian kingdom, which caused a mass exodus of the population. In the XIII-XIV centuries, there were especially many Armenians. Crimea is even called “maritime Armenia” in some Genoese documents. In a number of cities, including the largest city of the peninsula at that time, Kafe (Feodosia), Armenians made up the majority of the population. Hundreds of Armenian churches with schools were built on the peninsula. At the same time, some Crimean Armenians moved to the southern lands of Rus'. In particular, a very large Armenian community has developed in Lviv. Numerous Armenian churches, monasteries, and outbuildings are still preserved in Crimea.

Armenians lived throughout Crimea, but until 1475 the majority of Armenians lived in the Genoese colonies. Under pressure from the Catholic Church, some Armenians joined the union. Most Armenians, however, remained faithful to the traditional Armenian Gregorian Church. The religious life of the Armenians was very intense. There were 45 Armenian churches in one cafe. The Armenians were governed by their community elders. The Armenians were judged according to their own laws, according to their own code of justice.

The Armenians were engaged in trade and financial activities, among them there were many skilled artisans and builders. In general, the Armenian community flourished in the 13th-15th centuries.

In 1475, Crimea became dependent on the Ottoman Empire, with the cities of the southern coast, where the majority of Armenians lived, coming under the direct control of the Turks. The conquest of Crimea by the Turks was accompanied by the death of many Armenians and the removal of part of the population into slavery. The Armenian population declined sharply. Only in the 17th century did their numbers begin to increase.

During three centuries of Turkish rule, many Armenians converted to Islam, which led to their assimilation by the Tatars. Among the Armenians who retained the Christian faith, the Tatar language and oriental customs became widespread. Nevertheless, the Crimean Armenians as an ethnic group did not disappear. The vast majority of Armenians (up to 90%) lived in cities, engaged in trade and crafts.

In 1778, the Armenians, together with the Greeks, were evicted to the Azov region, to the lower reaches of the Don. In total, according to the reports of A.V. Suvorov, 12,600 Armenians were evicted. They founded the city of Nakhichevan (now part of Rostov-on-Don), as well as 5 villages. Only 300 Armenians remained in Crimea.

However, many Armenians soon returned to Crimea, and in 1811 they were officially allowed to return to their former place of residence. About a third of Armenians took advantage of this permission. Temples, lands, city blocks were returned to them; Urban national self-governing communities were created in Old Crimea and Karasubazar, and a special Armenian court operated until the 1870s.

The result of these government measures, along with the entrepreneurial spirit characteristic of Armenians, was the prosperity of this Crimean ethnic group. The 19th century in the life of the Crimean Armenians was marked by remarkable achievements, especially in the field of education and culture, associated with the names of the artist I. Aivazovsky, composer A. Spendiarov, artist V. Surenyants, etc. Admiral of the Russian fleet Lazar Serebryakov (Artsatagortsyan) distinguished himself in the military field ), who founded the port city of Novorossiysk in 1838. Crimean Armenians are also represented quite significantly among bankers, ship owners, and entrepreneurs.

The Crimean Armenian population was constantly replenished due to the influx of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire. By the time of the October Revolution, there were 17 thousand Armenians on the peninsula. 70% of them lived in cities.

The years of civil war took a heavy toll on the Armenians. Although some prominent Bolsheviks emerged from the Crimean Armenians (for example, Nikolai Babakhan, Laura Bagaturyants, etc.), who played a large role in the victory of their party, still a significant part of the Armenians of the peninsula belonged, in Bolshevik terminology, to “bourgeois and petty-bourgeois elements” . The war, repressions of all Crimean governments, the famine of 1921, the emigration of Armenians, among whom there were indeed representatives of the bourgeoisie, led to the fact that by the beginning of the 20s the Armenian population had decreased by a third. In 1926, there were 11.5 thousand Armenians in Crimea. By 1939, their number reached 12.9 thousand (1.1%).

In 1944, the Armenians were deported. After 1956, the return to Crimea began. At the end of the twentieth century, there were about 5 thousand Armenians in Crimea. However, the name of the Crimean city of Armyansk will forever remain a monument to the Crimean Armenians.

Karaites

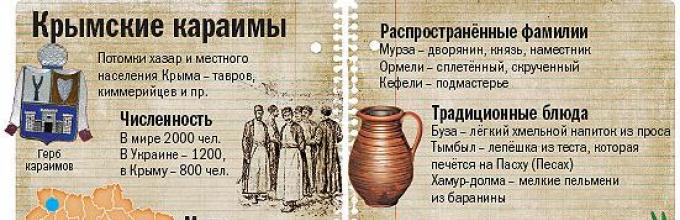

Crimea is the homeland of one of the small ethnic groups - the Karaites. They belong to the Turkic peoples, but differ in their religion. Karaites are Judaists, and they belong to a special branch of Judaism, whose representatives are called Karaites (literally “readers”). The origin of the Karaites is mysterious. The first mention of the Karaites dates back only to 1278, but they lived in Crimea several centuries earlier. The Karaites are probably descendants of the Khazars.

The Turkic origin of the Crimean Karaites has been proven by anthropological research. The blood groups of the Karaites and their anthropological appearance are more characteristic of Turkic ethnic groups (for example, the Chuvash) than of Semites. According to anthropologist Academician V.P. Alekseev, who studied in detail the craniology (structure of skulls) of the Karaites, this ethnic group actually arose from the mixing of the Khazars with the local population of Crimea.

Let us recall that the Khazars owned Crimea in VIII-X centuries. By religion, the Khazars were Jews, without being ethnic Jews. It is quite possible that some Khazars who settled in the mountainous Crimea retained the Jewish faith. True, the only problem with the Khazar theory of the origin of the Karaites is the fundamental fact that the Khazars accepted Orthodox Talmudic Judaism, and the Karaites even have the name of a different direction in Judaism. But the Crimean Khazars, after the fall of Khazaria, could well have moved away from Talmudic Judaism, if only because the Talmudic Jews had not previously recognized the Khazars, like other Jews of non-Jewish origin, as their coreligionists. When the Khazars adopted Judaism, the teachings of the Karaites were just emerging among the Jews in Baghdad. It is clear that those Khazars who retained their faith after the fall of Khazaria could take a direction in religion that emphasized their difference from the Jews. Enmity between the “Talmudists” (that is, the bulk of the Jews) and the “readers” (Karaites) has always been characteristic of the Jews of Crimea. The Crimean Tatars called the Karaites “Jews without sidelocks.”

After the defeat of Khazaria by Svyatoslav in 966, the Karaites maintained independence within the boundaries of the historical territory of Kyrk Yera - a district between the Alma and Kachi rivers and gained their own statehood within a small principality with its capital in the fortified city of Kale (now Chufut-Kale). Here resided their prince - sar, or biy, in whose hands was the administrative, civil and military power, and the spiritual head - kagan, or gakhan - of all the Karaites of Crimea (and not just the principality). His competence also included judicial and legal activities. The duality of power, expressed in the presence of both secular and spiritual heads, was inherited by the Karaites from the Khazars.

In 1246, the Crimean Karaites partially moved to Galicia, and in 1397-1398, part of the Karaite warriors (383 families) came to Lithuania. Since then, in addition to their historical homeland, Karaites have constantly lived in Galicia and Lithuania. In their places of residence, the Karaites enjoyed the kind attitude of the surrounding authorities, preserved their national identity, and had certain benefits and advantages.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Prince Eliazar voluntarily submitted Crimean Khan. In gratitude, the khan gave the Karaites autonomy in religious affairs,

The Karaites lived in Crimea, not particularly standing out among the local residents. They made up the majority of the population of the cave city of Chufut-Kale, inhabited neighborhoods in Old Crimea, Gezlev (Evpatoria), Cafe (Feodosia).

The annexation of Crimea to Russia became the finest hour for this people. The Karaites were exempt from many taxes, they were allowed to purchase land, which turned out to be very profitable when many lands were empty after the eviction of the Greeks, Armenians and the emigration of many Tatars. The Karaites were exempt from conscription, although their voluntary enrollment military service welcomed. Many Karaites actually chose military professions. Quite a few of them distinguished themselves in battles in defense of the Fatherland. Among them, for example, are the heroes of the Russian-Japanese War, Lieutenant M. Tapsachar, General Y. Kefeli. 500 career officers and 200 volunteers of Karaite origin took part in the First World War. Many became Knights of St. George, and a certain Gammal, a brave ordinary soldier, promoted to officer on the battlefield, earned a full set of soldier's St. George's Crosses and at the same time also an officer's St. George's Cross.

The small Karaite people became one of the most educated and richest nations Russian Empire. The Karaites almost monopolized the tobacco trade in the country. By 1913, there were 11 millionaires among the Karaites. The Karaites were experiencing a demographic explosion. By 1914, their number reached 16 thousand, of which 8 thousand lived in Crimea (at the end of the 18th century there were about 2 thousand).

Prosperity ended in 1914. Wars and revolution led to the loss of the Karaites' previous economic position. In general, the Karaites as a whole did not accept the revolution. Most of the officers and 18 generals from among the Karaites fought in the White army. Solomon Crimea was Minister of Finance in Wrangel's government.

As a result of wars, famine, emigration and repression, the number sharply decreased, primarily due to the military and civilian elite. In 1926, 4,213 Karaites remained in Crimea.

Over 600 Karaites took part in the Great Patriotic War, most were awarded military awards, more than half died or went missing. Artilleryman D. Pasha, naval officer E. Efet and many others became famous among the Karaites in the Soviet army. The most famous of the Soviet Karaite military leaders was Colonel General V.Ya. Kolpakchi, participant in the First World War and the Civil War, military adviser in Spain during the war of 1936-39, commander of armies during the Great War Patriotic War. It should be noted that the Karaites often include Marshal R. Ya. Malinovsky (1898-1967), twice Hero Soviet Union, Minister of Defense of the USSR in 1957-67, although his Karaite origin has not been proven.

In other areas the Karaites also gave a large number outstanding people. The famous intelligence officer, diplomat and at the same time writer I. R. Grigulevich, composer S. M. Maikapar, actor S. Tongur, and many others - all these are Karaites.

Mixed marriages, linguistic and cultural assimilation, low birth rates and emigration mean that the number of Karaites is declining. In the Soviet Union, according to the 1979 and 1989 censuses, there were 3,341 and 2,803 Karaites living respectively, including 1,200 and 898 Karaites in Crimea. In the 21st century, there are about 800 Karaites left in Crimea.

Krymchaks

Crimea is also the homeland of another Jewish ethnic group - the Krymchaks. Actually, Krymchaks, like Karaites, are not Jews. At the same time, they profess Talmudic Judaism, like most Jews in the world, their language is close to Crimean Tatar.

Jews appeared in Crimea even BC, as evidenced by Jewish burials, remains of synagogues, and inscriptions in Hebrew. One of these inscriptions dates back to the 1st century BC. In the Middle Ages, Jews lived in the cities of the peninsula, engaging in trade and crafts. Back in the 7th century, the Byzantine Theophanes the Confessor wrote about the large number of Jews living in Phanagoria (on Taman) and other cities on the northern shore of the Black Sea. In 1309, a synagogue was built in Feodosia, which testified to the large number of Crimean Jews.

It should be noted that mainly Crimean Jews came from the descendants of local residents who converted to Judaism, and not from the Jews of Palestine who emigrated here. Documents dating back to the 1st century have reached our time on the emancipation of slaves subject to their conversion to Judaism by their Jewish owners.

It should be noted that mainly Crimean Jews came from the descendants of local residents who converted to Judaism, and not from the Jews of Palestine who emigrated here. Documents dating back to the 1st century have reached our time on the emancipation of slaves subject to their conversion to Judaism by their Jewish owners.

Conducted in the 20s. studies of the blood groups of the Krymchaks conducted by V. Zabolotny confirmed that the Krymchaks did not belong to the Semitic peoples. However, the Jewish religion contributed to the Jewish self-identification of the Krymchaks, who considered themselves Jews.

The Turkic language (close to the Crimean Tatar), eastern customs and way of life, which distinguished the Crimean Jews from their fellow tribesmen in Europe, spread among them. Their self-name became the word “Krymchak”, meaning in Turkic a resident of Crimea. By the end of the 18th century, about 800 Jews lived in Crimea.

After the annexation of Crimea to Russia, the Krymchaks remained a poor and small religious community. Unlike the Karaites, the Krymchaks did not show themselves in any way in commerce and politics. True, their numbers began to increase rapidly due to high natural growth. By 1912 there were 7.5 thousand people. The civil war, accompanied by numerous anti-Jewish massacres carried out by all the changing authorities in Crimea, famine and emigration led to a sharp reduction in the number of Crimeans. In 1926 there were 6 thousand people.

During the Great Patriotic War, most Crimeans were exterminated by the German occupiers. After the war, no more than 1.5 thousand Crimeans remained in the USSR.

Nowadays, emigration, assimilation (leading to the fact that Crimeans associate themselves more with Jews), emigration to Israel and the USA, and depopulation finally put an end to the fate of this small Crimean ethnic group.

And yet, let us hope that the small ancient ethnic group that gave Russia the poet I. Selvinsky, the partisan commander, Hero of the Soviet Union Ya. I. Chapichev, the great Leningrad engineer M. A. Trevgoda, State Prize laureate, and a number of other prominent scientists, art, politics and economics will not disappear.

Jews

Jews speaking Yiddish were incomparably more numerous in Crimea. Since Crimea was part of the Pale of Settlement, quite a lot of Jews from the right bank of Ukraine began to settle in this fertile land. In 1897, 24.2 thousand Jews lived in Crimea. By the revolution their numbers had doubled. As a result, Jews became one of the largest and most visible ethnic groups on the peninsula.

Despite the reduction in the number of Jews during the civil war, they still remained the third (after Russians and Tatars) ethnic group of Crimea. In 1926 there were 40 thousand (5.5%). By 1939, their number had increased to 65 thousand (6% of the population).

The reason was simple - Crimea in 20-40. was considered not only and so much by Soviet as by world Zionist leaders as a “national home” for Jews around the world. It is no coincidence that the resettlement of Jews to Crimea took on significant proportions. It is significant that while urbanization was taking place throughout Crimea, as well as throughout the country as a whole, the opposite process was taking place among Crimean Jews.

The project for the resettlement of Jews to Crimea and the creation of Jewish autonomy there was developed back in 1923 by the prominent Bolshevik Yu. Larin (Lurie), and in the spring of the following year was approved by the Bolshevik leaders L. D. Trotsky, L. B. Kamenev, N. I. Bukharin . It was planned to resettle 96 thousand Jewish families (about 500 thousand people) to Crimea. However, there were more optimistic figures - 700 thousand by 1936. Larin openly spoke about the need to create a Jewish republic in Crimea.

On December 16, 1924, even a document was signed with such an intriguing title: “On Crimean California” between the “Joint” (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, as the American Jewish organization that represented in the early years Soviet power USA) and the Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR. Under this agreement, the Joint allocated $1.5 million per year to the USSR for the needs of Jewish agricultural communes. The fact that most Jews in Crimea did not engage in agriculture did not matter.

In 1926, the head of the Joint, James N. Rosenberg, came to the USSR; as a result of meetings with the country’s leaders, an agreement was reached on D. Rosenberg’s financing of activities for the resettlement of Jews from Ukraine and Belarus to the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Help was also provided by the French Jewish Society, the American Society for the Relief of Jewish Colonization in Soviet Russia and other organizations of a similar type. On January 31, 1927, a new agreement was concluded with Agro-Joint (a subsidiary of the Joint itself). According to it, the organization allocated 20 million rubles. To organize the resettlement, the Soviet government allocated 5 million rubles for these purposes.

The planned resettlement of Jews began already in 1924. The reality turned out to be not so optimistic.

Over 10 years, 22 thousand people settled in Crimea. They were provided with 21 thousand hectares of land, 4,534 apartments were built. The Crimean Republican Representative Office of the Committee on the Land Question of Working Jews under the Presidium of the Council of Nationalities of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (KomZet) dealt with the issues of resettlement of Jews. Note that for every Jew there was almost 1 thousand hectares of land. Almost every Jewish family received an apartment. (This is in the context of a housing crisis, which in the resort Crimea was even more acute than in the country as a whole).

Most of the settlers did not cultivate the land and mostly dispersed to cities. By 1933, only 20% of the settlers from 1924 remained on the collective farms of the Freidorf MTS, and 11% on the Larindorf MTS. On some collective farms the turnover rate reached 70%. By the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, only 17 thousand Jews in Crimea lived in rural areas. The project failed. In 1938, the resettlement of Jews was stopped, and KomZet was dissolved. The Joint branch in the USSR was liquidated by the Decree of the Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks of May 4, 1938.

The massive outflow of immigrants meant that the Jewish population did not grow as significantly as might have been expected. By 1941, 70 thousand Jews lived in Crimea (excluding Krymchaks).

During the Great Patriotic War, more than 100 thousand Crimeans, including many Jews, were evacuated from the peninsula. Those who remained in Crimea had to experience all the features of Hitler's “new order” when the occupiers began the final solution to the Jewish question. And already on April 26, 1942, the peninsula was declared “cleared of Jews.” Almost everyone who did not have time to evacuate died, including most of the Crimeans.

However, the idea of Jewish autonomy not only did not disappear, but also acquired a new breath.

The idea of creating a Jewish Autonomous Republic in Crimea arose again in the late spring of 1943, when the Red Army, having defeated the enemy at Stalingrad and in the North Caucasus, liberated Rostov-on-Don and entered the territory of Ukraine. In 1941, about 5-6 million people fled from these territories or were evacuated in a more organized manner. Among them, more than a million were Jews.

In practical terms, the question of creating a Jewish Crimean autonomy arose in preparation for the propaganda and business trip of two prominent Soviet Jews - the actor S. Mikhoels and the poet I. Fefer - to the USA in the summer of 1943. It was assumed that American Jews would be enthusiastic about the idea and would agree to finance all the costs associated with it. Therefore, the two-person delegation traveling to the United States received permission to discuss this project in Zionist organizations.

Among Jewish circles in the United States, the creation of a Jewish republic in Crimea did indeed seem quite possible. Stalin did not seem to mind. Members of the JAC (Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee), created during the war, during their visits to the United States, spoke openly about the creation of a republic in Crimea, as if it were something a foregone conclusion.

Of course, Stalin had no intention of creating Israel in Crimea. He wanted to make maximum use of the influential Jewish community in the United States for Soviet interests. As I wrote Soviet intelligence officer P. Sudoplatov, head of the 4th Directorate of the NKVD, responsible for special operations, “immediately after the formation of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Soviet intelligence decided to use the connections of the Jewish intelligentsia to find out the possibility of obtaining additional economic assistance through Zionist circles... For this purpose, Mikhoels and Fefer, our trusted agent, were instructed to probe the reaction of influential Zionist organizations to the creation of a Jewish republic in Crimea. This task of special reconnaissance sounding was successfully completed.”

In January 1944, some Jewish leaders of the USSR drafted a memorandum to Stalin, the text of which was approved by Lozovsky and Mikhoels. The “Note,” in particular, said: “With the aim of normalizing economic growth and the development of Jewish Soviet culture, with the aim of maximizing the mobilization of all the forces of the Jewish population for the benefit of the Soviet Motherland, with the aim complete equation position of the Jewish masses among the fraternal peoples, we consider it timely and appropriate, in order to solve post-war problems, to raise the question of creating a Jewish Soviet socialist republic... It seems to us that one of the most suitable areas would be the territory of Crimea, which best meets the requirements both in terms of capacity for resettlement, and due to the existing successful experience in the development of Jewish national areas there... In the construction of the Jewish Soviet Republic, the Jewish people of all countries of the world, wherever they may be, would provide us with significant assistance.”

Even before the liberation of Crimea, the Joint insisted on the transfer of Crimea to the Jews, the eviction of the Crimean Tatars, the withdrawal of the Black Sea Fleet from Sevastopol, and the formation of an INDEPENDENT Jewish state in Crimea. Moreover, the opening of the 2nd front in 1943. the Jewish lobby linked it with Stalin's fulfillment of his debt obligations to the Joint.

The deportation of Tatars and representatives of other Crimean ethnic groups from Crimea led to the desolation of the peninsula. It seemed that there would now be plenty of room for the arriving Jews.

According to the famous Yugoslav figure M. Djilas, when asked about the reasons for the expulsion of half the population from Crimea, Stalin referred to the obligations given to Roosevelt to clear Crimea for Jews, for which the Americans promised a preferential 10 billion loan.

However, the Crimean project was not implemented. Stalin, having made maximum use of financial assistance from Jewish organizations, did not create Jewish autonomy in Crimea. Moreover, even the return to Crimea of those Jews who were evacuated during the war turned out to be difficult. However, in 1959 there were 26 thousand Jews in Crimea. Subsequently, emigration to Israel led to a significant reduction in the number of Crimean Jews.

Crimean Tatars

Since the time of the Huns and the Khazar Kaganate, Turkic peoples began to penetrate into Crimea, inhabiting only the steppe part of the peninsula. In 1223, the Mongol-Tatars attacked Crimea for the first time. But it was only a raid. In 1239, Crimea was conquered by the Mongols and became part of the Golden Horde. The southern coast of Crimea was under the rule of the Genoese; in the mountainous Crimea there was a small principality of Theodoro and an even smaller principality of the Karaites.

Gradually, a new Turkic ethnic group began to emerge from the mixture of many peoples. At the beginning of the 14th century, the Byzantine historian George Pachymer (1242-1310) wrote: “Over time, the peoples who lived inside those countries mixed with them (Tatars - ed.), I mean: Alans, Zikkhs (Caucasian Circassians who lived on the coast Taman Peninsula - ed.), Goths, Russians and other peoples different from them, learn their customs, along with their customs they acquire language and clothing and become their allies." The unifying principles for the emerging ethnic group were Islam and the Turkic language. Gradually, the Tatars of Crimea (who, however, did not call themselves Tatars at that time) became very numerous and powerful. It is no coincidence that it was the Horde governor in Crimea, Mamai, who managed to temporarily seize power in the entire Golden Horde. The capital of the Horde governor was the city of Kyrym - “Crimea” (now the city of Old Crimea), built by the Golden Horde in the valley of the Churuk-Su river in the southeast of the Crimean peninsula. In the 14th century, the name of the city of Crimea gradually passed to the entire peninsula. Residents of the peninsula began to call themselves “kyrymly” - Crimeans. The Russians called them Tatars, like all eastern Muslim peoples. The Crimeans began to call themselves Tatars only when they were already part of Russia. But for convenience, we will still call them Crimean Tatars, even when talking about earlier eras.

In 1441, the Tatars of Crimea created their own khanate under the rule of the Girey dynasty.

Initially, the Tatars were inhabitants of the steppe Crimea; the mountains and the southern coast were still inhabited by various Christian peoples, and they outnumbered the Tatars. However, as Islam spread, converts from the indigenous population began to join the ranks of the Tatars. In 1475, the Ottoman Turks defeated the colonies of the Genoese and Theodoro, which led to the subjugation of the entire Crimea to the Muslims.

At the very beginning of the 16th century, Khan Mengli-Girey, having defeated the Great Horde, brought entire uluses of Tatars from the Volga to Crimea. Their descendants were subsequently called Yavolga (that is, Trans-Volga) Tatars. Finally, already in the 17th century, many Nogais settled in the steppes near Crimea. All this led to the strongest Turkization of Crimea, including part of the Christian population.

A significant part of the mountain population fled, amounting to special group Tatars, known as "Tats". Racially, the Tats belong to the Central European race, that is, they are externally similar to representatives of the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. Also, many residents of the southern coast, descendants of the Greeks, Tauro-Scythians, Italians and other inhabitants of the region, who converted to Islam, gradually joined the ranks of the Tatars. Until the deportation of 1944, residents of many Tatar villages on the South Bank retained elements of Christian rituals that they inherited from their Greek ancestors. Racially, the South Coast residents belong to the South European (Mediterranean) race and are similar in appearance to the Turks, Greeks, and Italians. They formed a special group of Crimean Tatars - the Yalyboylu. Only the steppe Nogai retained elements of traditional nomadic culture and retained some Mongoloid features in their physical appearance.

The descendants of captives and female captives also joined the Crimean Tatars, mainly from Eastern Slavs remaining on the peninsula. Slaves who became wives of the Tatars, as well as some men from among the captives who converted to Islam and, thanks to their knowledge of some useful crafts, also became Tatars. “Tumas,” as the children of Russian captives born in Crimea were called, made up a very large part of the Crimean Tatar population. This is indicative historical fact: In 1675, Zaporozhye ataman Ivan Sirko, during a successful raid into Crimea, freed 7 thousand Russian slaves. However, on the way back, approximately 3 thousand of them asked Sirko to let them go back to Crimea. Most of these slaves were Muslims or Thums. Sirko let them go, but then ordered his Cossacks to catch up and kill them all. This order was carried out. Sirko drove up to the place of the massacre and said: “Forgive us, brothers, and sleep here until the Last Judgment of God, instead of multiplying in the Crimea, among the infidels, on our brave Christian heads and on your eternal death without forgiveness.”

Of course, despite such ethnic cleansing, the number of Tums and Otatar Slavs in Crimea remained significant.

After the annexation of Crimea to Russia, some Tatars left their homeland, moving to Ottoman Empire. By the beginning of 1785, 43.5 thousand male souls were counted in Crimea. Crimean Tatars made up 84.1% of all residents (39.1 thousand people). Despite the high natural increase, the share of Tatars was constantly decreasing due to the influx of new Russian settlers and foreign colonists to the peninsula. Nevertheless, the Tatars made up the vast majority of the population of Crimea.

After the Crimean War of 1853-56. under the influence of Turkish agitation, a movement for emigration to Turkey began among the Tatars. Military actions devastated Crimea, Tatar peasants did not receive any compensation for their material losses, so there were additional reasons for emigration.

Already in 1859, the Nogais of the Azov region began leaving for Turkey. In 1860, a mass exodus of Tatars began from the peninsula itself. By 1864, the number of Tatars in Crimea had decreased by 138.8 thousand people. (from 241.7 to 102.9 thousand people). The scale of emigration frightened the provincial authorities. Already in 1862, cancellations of previously issued foreign passports and refusals to issue new ones began. However, the main factor in stopping emigration was the news of what awaited the Tatars in Turkey of the same faith. A lot of Tatars died on the way on overloaded feluccas in the Black Sea. The Turkish authorities simply threw the settlers on the shore without providing them with any food. Up to a third of the Tatars died in the first year of life in a country of the same faith. And now re-emigration to Crimea has already begun. But neither the Turkish authorities, who understood that the return of Muslims from under the rule of the caliph again to the rule of the Russian Tsar would make an extremely unfavorable impression on the Muslims of the world, nor the Russian authorities, who also feared the return of embittered people who had lost everything, were not going to help the return to Crimea.

Smaller scale Tatar exoduses to the Ottoman Empire occurred in 1874-75, in the early 1890s, and in 1902-03. As a result, most of the Crimean Tatars found themselves outside of Crimea.

So the Tatars of their own free will became an ethnic minority in their land. Thanks to high natural growth, their number reached 216 thousand people by 1917, which accounted for 26% of the population of Crimea. In general, during the civil war the Tatars were politically split, fighting in the ranks of all the fighting forces.

The fact that the Tatars made up a little more than a quarter of the population of Crimea did not bother the Bolsheviks. Guided by their national policy, they went to create an autonomous republic. On October 18, 1921, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR issued a decree on the formation of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the RSFSR. On November 7, the 1st All-Crimean Constituent Congress of Soviets in Simferopol proclaimed the formation of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, elected the leadership of the republic and adopted its Constitution.

This republic was not, strictly speaking, purely national. Note that it was not called Tatar. But the “indigenization of personnel” was consistently carried out here too. Most of the leading personnel were also Tatars. Tatar language was, along with Russian, the language of office work and schooling. In 1936, there were 386 Tatar schools in Crimea.

During the Great Patriotic War, the fate of the Crimean Tatars developed dramatically. Some Tatars fought honestly in the ranks of the Soviet army. Among them were 4 generals, 85 colonels and several hundred officers. 2 Crimean Tatars steel complete gentlemen Order of Glory, 5 - Heroes of the Soviet Union, pilot Amet Khan Sultan - twice a Hero.

In their native Crimea, some Tatars fought in partisan detachments. Thus, as of January 15, 1944, there were 3,733 partisans in Crimea, of which 1,944 were Russians, 348 Ukrainians, 598 Crimean Tatars. In retaliation for the actions of the partisans, the Nazis burned 134 settlements in the foothills and mountainous areas of Crimea, 132 of which were predominantly Crimean Tatar.

However, you can’t erase the words from the song. During the occupation of Crimea, many Tatars found themselves on the side of the Nazis. 20 thousand Tatars (that is, 1/10 of the entire Tatar population) served in the ranks of volunteer formations. They were involved in the fight against partisans, and were especially active in the reprisals against civilians.

In May 1944, literally immediately after the liberation of Crimea, the Crimean Tatars were deported. The total number of deportees was 191 thousand people. Family members of Soviet army soldiers, participants in the underground and partisan struggle, as well as Tatar women who married representatives of a different nationality were exempt from deportation.

Beginning in 1989, the Tatars began returning to Crimea. The repatriation was actively promoted by the Ukrainian authorities, hoping that the Tatars would weaken Russian movement for the annexation of Crimea to Russia. In part, these expectations of the Ukrainian authorities were confirmed. In the elections to the Ukrainian parliament, Tatars en masse voted for Rukh and other independent parties.

In 2001, Tatars already made up 12% of the peninsula's population - 243,433 people.

Other ethnic groups of Crimea

Since its annexation to Russia, representatives of several small ethnic groups have also lived on the peninsula, who also became Crimeans. We are talking about Crimean Bulgarians, Poles, Germans, Czechs. Living far from their main ethnic territory, these Crimeans became independent ethnic groups.

Bulgarians appeared in Crimea at the end of the 18th century, immediately after the annexation of the peninsula to Russia. The first Bulgarian settlement in Crimea appeared in 1801. Russian authorities they valued the hard work of the Bulgarians, as well as their ability to farm in subtropical conditions. Therefore, the Bulgarian settlers received from the treasury a daily allowance of 10 kopecks per capita, and each Bulgarian family was allocated up to 60 acres of state land. Each Bulgarian immigrant was given benefits in taxes and other financial obligations for 10 years. After their expiration, they were largely maintained for the next 10 years: the Bulgarians were subject to only a tax of 15-20 kopecks per tithe. Only after twenty years had passed after their arrival in Crimea, immigrants from Turkey were equalized in taxation with the Tatars, immigrants from Ukraine and Russia.

The second wave of resettlement of Bulgarians to Crimea occurred during the Russian-Turkish War of 1828-1829. About 1000 people arrived. Finally, in the 60s. In the 19th century, the third wave of Bulgarian settlers arrived in Crimea. In 1897, 7,528 Bulgarians lived in Crimea. It should be noted that the religious and linguistic closeness of the Bulgarians and Russians led to the assimilation of part of the Crimean Bulgarians.

Wars and revolutions had a hard impact on the Bulgarians of Crimea. Their numbers grew rather slowly due to assimilation. In 1939, 17.9 thousand Bulgarians lived in Crimea (or 1.4% of the total population of the peninsula).

In 1944, the Bulgarians were deported from the peninsula, although, unlike the Crimean Tatars, there was no evidence of Bulgarian cooperation with the German occupiers. Nevertheless, the entire Crimean-Bulgarian ethnic group was deported. After rehabilitation, the slow process of repatriation of Bulgarians to Crimea began. At the beginning of the 21st century, slightly more than 2 thousand Bulgarians lived in Crimea.

Czechs appeared in Crimea a century and a half ago. In the 60s of the 19th century, 4 Czech colonies appeared. The Czechs were different high level education, which paradoxically contributed to their rapid assimilation. In 1930, there were 1,400 Czechs and Slovaks in Crimea. At the beginning of the 21st century, only 1 thousand people of Czech origin lived on the peninsula.

Another Slavic ethnic group of Crimea is represented Poles. The first settlers were able to arrive in Crimea already in 1798, although the mass migration of Poles to Crimea began only in the 60s of the 19th century. It should be noted that since the Poles did not inspire confidence, especially after the uprising of 1863, they were not only not given any benefits like colonists of other nationalities, but were even forbidden to settle in separate settlements. As a result, “purely” Polish villages did not arise in Crimea, and the Poles lived together with the Russians. In all large villages, along with the church, there was also a church. There were also churches in all major cities - Yalta, Feodosia, Simferopol, Sevastopol. As religion lost its former influence on ordinary Poles, the Polish population of Crimea rapidly assimilated. At the end of the 20th century, about 7 thousand Poles (0.3% of the population) lived in Crimea.

Germans appeared in Crimea already in 1787. Since 1805, German colonies began to emerge on the peninsula with their own internal self-government, schools and churches. The Germans came from a wide variety of German lands, as well as from Switzerland, Austria and Alsace. In 1865 there were already 45 in Crimea settlements with the German population.

The benefits provided to the colonists, the favorable natural conditions of Crimea, and the hard work and organization of the Germans led the colonies to rapid economic prosperity. In turn, news of the economic successes of the colonies contributed to the further influx of Germans to Crimea. The colonists were characterized by a high birth rate, so the German population of Crimea grew rapidly. According to the first All-Russian census of 1897, 31,590 Germans lived in Crimea (5.8% of the total population), of which 30,027 were rural residents.

Almost all of the Germans were literate, and their standard of living was significantly above average. These circumstances affected the behavior of the Crimean Germans during Civil War.

Most of the Germans tried to be “above the fray” without participating in civil strife. But some Germans fought for Soviet power. In 1918, the First Yekaterinoslav Communist Cavalry Regiment was formed, which fought against the German occupiers in Ukraine and Crimea. In 1919, the First German Cavalry Regiment as part of Budyonny's army led an armed struggle in the south of Ukraine against Wrangel and Makhno. Some Germans fought on the side of the whites. So, Yegerskaya fought in Denikin’s army rifle brigade from the Germans. A special regiment of Mennonites fought in Wrangel's army.

In November 1920, Soviet power was finally established in Crimea. The Germans who recognized it continued to live in their colonies and their farms, practically without changing their way of life: the farms were still strong; children went to their own schools with teaching in German; all issues were resolved jointly within the colonies. Two German districts were officially formed on the peninsula - Biyuk-Onlarsky (now Oktyabrsky) and Telmanovsky (now Krasnogvardeysky). Although many Germans lived in other places in Crimea. 6% of the German population produced 20% of the gross income from all agricultural products of the Crimean ASSR. Demonstrating complete loyalty to the Soviet government, the Germans tried to “stay out of politics.” It is significant that during the 20s only 10 Crimean Germans joined the Bolshevik Party.

The standard of living of the German population continued to be much higher than in other national groups, so the outbreak of collectivization, followed by mass dispossession, affected primarily German farms. Despite losses in the Civil War, repression and emigration, the German population of Crimea continued to increase. In 1921, there were 42,547 Crimean Germans. (5.9% of the total population), in 1926 - 43,631 people. (6.1%), 1939 - 51,299 people. (4.5%), 1941 - 53,000 people. (4.7%).

The Great Patriotic War became the greatest tragedy for the Crimean-German ethnic group. In August-September 1941, more than 61 thousand people were deported (including approximately 11 thousand people of other nationalities related to the Germans by family ties). The final rehabilitation of all Soviet Germans, including Crimean ones, followed only in 1972. From that time on, the Germans began to return to Crimea. In 1989, 2,356 Germans lived in Crimea. Alas, some of the deported Crimean Germans emigrate to Germany, and not to their peninsula.

East Slavs

The majority of the inhabitants of Crimea are Eastern Slavs (we will call them that politically correctly, taking into account the Ukrainian identity of some Russians in Crimea).

As already mentioned, the Slavs have lived in Crimea since ancient times. In the 10th-13th centuries, the Tmutarakan principality existed in the eastern part of Crimea. And during the era of the Crimean Khanate, some captives from Great and Little Rus', monks, merchants, and diplomats from Russia were constantly on the peninsula. Thus, the Eastern Slavs were part of the permanent indigenous population of Crimea for centuries.

In 1771, when Crimea was occupied by Russian troops, about 9 thousand Russian freed slaves were freed. Most of them remained in Crimea, but as personally free Russian subjects.

With the annexation of Crimea to Russia in 1783, the settlement of the peninsula by settlers from all over the Russian Empire began. Literally immediately after the 1783 manifesto on the annexation of Crimea, by order of G. A. Potemkin, soldiers of the Ekaterinoslav and Phanagorian regiments were left to live in Crimea. Married soldiers were given leave at government expense so that they could take their families to Crimea. In addition, girls and widows were summoned from all over Russia who agreed to marry soldiers and move to Crimea.

Many nobles who received estates in Crimea began to transfer their serfs to Crimea. State peasants also moved to the state-owned lands of the peninsula.

Already in 1783-84, in the Simferopol district alone, settlers formed 8 new villages and, in addition, settled together with the Tatars in three villages. In total, by the beginning of 1785, 1,021 males from among the Russian settlers were counted here. New Russian-Turkish war 1787-91 somewhat slowed down the influx of immigrants to Crimea, but did not stop it. During 1785 - 1793, the number of registered Russian settlers reached 12.6 thousand male souls. In general, Russians (together with Little Russians) already made up approximately 5% of the peninsula’s population over the several years that Crimea was part of Russia. In fact, there were even more Russians, since many fugitive serfs, deserters and Old Believers sought to avoid any contact with representatives of the official authorities. Freed former slaves were not counted. In addition, strategically important Crimea Tens of thousands of military personnel are constantly present.

The constant migration of Eastern Slavs to Crimea continued throughout the 19th century. After the Crimean War and the mass emigration of Tatars to the Ottoman Empire, which led to the emergence large quantities"no man's" fertile land, new thousands of Russian immigrants arrived in Crimea.

Gradually, the local Russian residents began to develop special features of their economy and way of life, caused both by the peculiarities of the geography of the peninsula and its multinational character. In a statistical report on the population of the Tauride province for 1851, it was noted that Russians (Great Russians and Little Russians) and Tatars wear clothes and shoes, differing little from each other. The utensils used are both clay, made at home, and copper, made by Tatar craftsmen. The usual Russian carts were soon replaced by Tatar carts upon arrival in Crimea.

From the second half of the 19th century centuries, the main wealth of Crimea - its nature, made the peninsula a center of recreation and tourism. Palaces of the imperial family and influential nobles began to appear on the coast, and thousands of tourists began to arrive for rest and treatment. Many Russians began to strive to settle in the fertile Crimea. So the influx of Russians into Crimea continued. At the beginning of the 20th century, Russians became the predominant ethnic group in Crimea. Considering high degree Russification of many Crimean ethnic groups, the Russian language and culture (which had largely lost their local characteristics) absolutely prevailed in Crimea.

After the revolution and the Civil War, Crimea, which turned into an “all-Union health resort,” continued to attract Russians. However, Little Russians, who were considered a special people - Ukrainians, also began to arrive. Their share of the population in the 20-30s increased from 8% to 14%.

In 1954 N.S. Khrushchev, with a voluntaristic gesture, annexed Crimea to the Ukrainian Soviet republic. The result was Ukrainization Crimean schools and offices. In addition, the number of Crimean Ukrainians has increased sharply. Actually, some of the “real” Ukrainians began to arrive in Crimea back in 1950, according to the government’s “Plans for the resettlement and transfer of the population to the collective farms of the Crimean region.” After 1954, new settlers from the western Ukrainian regions began to arrive in Crimea. For the move, the settlers were given entire carriages, which could accommodate all their property (furniture, utensils, decorations, clothing, multi-meter canvases of homespun), livestock, poultry, apiaries, etc. Numerous Ukrainian officials arrived in Crimea, which had the status of an ordinary region within the Ukrainian SSR . Finally, since it became prestigious to be Ukrainian, some Crimeans also turned into Ukrainians by passport.

In 1989, 2,430,500 people lived in Crimea (67.1% Russians, 25.8% Ukrainians, 1.6% Crimean Tatars, 0.7% Jews, 0.3% Poles, 0.1% Greeks).

The collapse of the USSR and the declaration of independence of Ukraine caused economic and demographic catastrophe in Crimea. In 2001, Crimea had a population of 2,024,056. But in fact, the demographic catastrophe of Crimea is even worse, since the population decline was partially compensated by the Tatars returning to Crimea.

In general, at the beginning of the 21st century, Crimea, despite its centuries-old multi-ethnicity, remains predominantly Russian in population. During its two decades as part of independent Ukraine, Crimea has repeatedly demonstrated its Russianness. Over the years, the number of Ukrainians and returning Crimean Tatars in Crimea has increased, thanks to which official Kyiv was able to gain a certain number of its supporters, but, nevertheless, the existence of Crimea within Ukraine seems problematic.

Crimean SSR (1921-1945). Questions and answers. Simferopol, "Tavria", 1990, p. 20

Sudoplatov P. A. Intelligence and the Kremlin. M., 1996, pp. 339-340

From secret archives Central Committee of the CPSU. Tasty peninsula. Note about Crimea / Comments by Sergei Kozlov and Gennady Kostyrchenko // Rodina. - 1991.-№11-12. - pp. 16-17

From the Cimmerians to the Crimeans. The peoples of Crimea from ancient times to the end of the 18th century. Simferopol, 2007, p. 232

Shirokorad A. B. Russian-Turkish wars. Minsk, Harvest, 2000, p. 55

Crimean Greeks are part of the Greek diaspora, which was formed differently in different periods of history and had certain ethnic, linguistic and cultural differences. Its appearance dates back to the 6th century. BC e., when the colonization of Crimea began by the ancient Greeks, who created on the western, southeastern and eastern coasts and on the Kerch Peninsula whole line policies: Kerkinitis, Panticapaeum, Feodosia, Chersonesos, etc., later united into 2 states - Bosporan Kingdom and the Republic of Chersonesos.

Ancient Greeks, being mainly engaged in agriculture, crafts and trade, introduced huge contribution V economic development and culture of Crimea. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, the ancient Greeks for the most part assimilated with the local (Tauro-Scythian) and alien (Sarmatian-Alan, Germanic, and later Turkic-Bulgar) populations, as well as with the Byzantines who moved to the peninsula, among whom there were also many Greeks.

The next wave of Greeks rushed into Crimea in the 11th – 13th centuries. in connection with the restoration of Byzantine power in Taurica, it caused the widespread spread of Christianity, the construction of churches, monasteries, castles, and fortresses. The main occupation of the Greeks during this period was cattle breeding, crafts, and trade. Many of them were Turkified by language, customs, and partly by religion. Most of the medieval Greek-Christians were resettled by the tsarist government in the Azov region in 1778, but soon some of them, by order of G. A. Potemkin, returned to the peninsula. At the same time, after the Kuchuk-Kainardzhi peace of 1774, the Greeks of the archipelago army formed by Count A. S. Orlov were settled in Kerch and Yenikal. After the annexation of Crimea to Russia, a battalion was created from them to guard the southern coast; later this battalion participated in Crimean War. 12 - 13 thousand Greeks fled to Crimea from Turkey, fleeing genocide, during the First World War (they were called “new Greeks”).

On the peninsula, the Greeks lived in small compact groups next to the Bulgarians, Russians, Ukrainians, Tatars and others in cities and 398 villages and hamlets, engaged mainly in gardening, melon growing, tobacco growing and trade, as well as viticulture and fishing. In 1939, 20,652 Greeks lived in Crimea. During the Great Patriotic War, many Crimean Greeks were at the front and very actively participated in the partisan and underground movement.

On June 14, 1944, all Crimean Greeks, including former front-line soldiers, partisans and underground fighters, were forcibly deported from Crimea “to other regions of the USSR.” Due to the fact that the Crimean Greeks did not cooperate with the Nazi occupiers, they did not need rehabilitation. Already in the 50s. some of them returned to the peninsula. Now this process has intensified. However, many of the Crimean Greeks emigrated and continue to emigrate to Greece.

The ancient Hellenes brought civilization to Crimea. They named the peninsula Taurida after the Taurian tribe that lived on it.

Great Colonization

The Greeks apparently knew about the existence of Crimea back in the era Mycenaean culture(XV-XII centuries BC). The myths of the Iliad and Odyssey, composed later, but reflecting the knowledge acquired during that period, speak of the Black Sea as Pontus Aksinsky, that is, inhospitable. It is described as eternally cold and shrouded in dark clouds. The Cimmerians who lived on its northern shore, according to the Greeks, lived immediately before the entrance to the afterlife kingdom of shadows.

The situation changed in the 8th century BC. e., when the Greeks, due to lack of land, were forced to move to widespread colonization of the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and adjacent inland seas.

The great Greek colonization was organized like this. The decision to create a colony and resettle some of the inhabitants there was made by the people's assembly of the polis or its aristocratic council. The head of the entire enterprise was appointed, bearing the title oikist. He had the highest power in the colony at first. The colony itself became an independent polis, but nominally recognized the authority of its metropolis and often turned to it in case of political difficulties.

To determine the place where to withdraw the colony, the policy sent a delegation to Delphi, to the authoritative pan-Greek oracle of Apollo. There the Pythia, inhaling sulfur fumes, uttered a prophecy. Of course, that was the ritual side of the matter. But it is characteristic that this was in charge of the priests of Apollo, who obviously structured the matter in such a way that different streams of colonists would not collide with each other in new places and would not interfere with each other. Apollo's oracle gave good advice. Thus, the great Greek colonization was a well-thought-out undertaking.

Greek colonies in Crimea

To begin developing the shores of the Black Sea, the Greeks first had to colonize the shores of the Bosphorus. On the northern coast of the Black Sea, Greek colonists appeared already in the 7th century BC. e. The first Hellenic colony in Tauris was, apparently, Panticapaeum (present-day Kerch), which arose at the end of the same century. It was founded by people from the city of Miletus on the western coast of Asia Minor.

The same Milesians in the 6th century BC. e. They founded Feodosia, and a number of cities appeared around Panticapaeum. At the beginning of the 5th century BC. e. all these cities (except Feodosia) united into the Bosporan kingdom. The latest of the Greek colonies in Tauris was Chersonesos (near present-day Sevastopol), founded by settlers from Heraclea Pontic (which itself was a colony) at the end of the 5th century BC. e.

There were no Greek colonies on the extreme southern coast of Crimea, where the climate is warmest, since there are no convenient bays there. Therefore, in a new place, the Greek colonists had to adapt to new conditions. Thus, it was impossible to grow olives here, so the olive oil so familiar to the Greeks had to be imported. At the very least, only grapevines grew here. And of course, wheat. After all, Greek colonization was initially undertaken with the expectation of seizing areas for growing bread for food.

Economy

The nature of the organization of agricultural production in the colonies depended on where the colonists themselves came from. In the Bosporan kingdom, created by the Milesians, the land was cultivated by free community members. Classical slavery also existed there, but mainly in the crafts. In Chersonesus, founded by the Heracleans, the economy was organized on a model close to Sparta. There, the conquered local population (helots) was attached to the land and cultivated it for the needs of the owners. The Chersonese lived in rich estates, on the lands of which enslaved Taurians worked.

The Chersonesos steadily expanded their possessions in Crimea, establishing new latifundia. A significant part of the flat territory in Western Crimea came under the control of the Chersonesos state, turned into fields for growing bread and vineyards. The borders of the state were marked by a fortified wall. The Chersonese state was not inferior in power to the Bosporus.

Political development

The Greek states in Crimea experienced a long history filled with internal political upheavals, wars with neighbors (among which the most trouble was caused by those who owned northern part Scythian peninsula), participation in big politics the ancient world.

Chersonesus stubbornly adhered to the previous order subsistence farming, without developing it, which ultimately led to its decline. The Bosporan kingdom gradually became the main intermediary in the grain trade of the entire Northern Black Sea region with the rest of the ancient world and flourished until the end of the 2nd century AD. e. It retained the attributes of independence at the very time when Chersonesus turned into nothing more than a military outpost of Rome on the northern shore of the Black Sea, a place of exile for political and religious dissidents (among whom was St. Clement, Pope of the first century of Christianity).

However, when at the end of the 4th century AD. e. The Bosporan kingdom fell under the blows of the “barbarians” (Goths and Huns), Chersonesus survived precisely for this reason, and after many centuries served as a stronghold of the Eastern Roman Empire - Byzantium.

Antiquity

Middle Ages

Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Greek territory in Crimea around 1265

New time

Population dynamics

- year, census: 2,795 people. (0.14%)

- year, census: 2,646 people. (0.14%)

Notes

Write a review about the article "Crimean Greeks"

Notes

An excerpt characterizing the Crimean Greeks

- Think, Isidora! I don't want to hurt you! – switching to “you,” Karaffa whispered in an insinuating voice. – Why don’t you want to help me?! I’m not asking you to betray your mother, or Meteora, I’m asking you to teach only what you yourself know about it! We could rule the world together! I would make you the queen of queens!.. Think, Isidora...I understood that something very bad was going to happen right now, but I simply didn’t have the strength to lie anymore...

– I will not help you simply because, by living longer than you are destined to do, you will destroy the best half of humanity... Precisely those who are the smartest and most gifted. You bring too much evil, Holiness... And you have no right to live long. Forgive me... – and, after a slight pause, she added very quietly. – But our life is not always measured only by the number of years lived, Your Holiness, and you know this very well...

- Well, Madonna, everything is your will... When you finish, you will be taken to your chambers.

And to my greatest surprise, without saying another word, he, as if nothing had happened, calmly got up and left, abandoning his unfinished, truly royal, dinner.... Again, this man’s restraint was amazing, forcing me to involuntarily respect at the same time, hating him for everything he had done...

The day passed in complete silence, and night was approaching. My nerves were tense to the limit - I was expecting trouble. Feeling its approach with all my being, I tried last bit of strength remain calm, but my hands were shaking from wild overexcitement, and a chilling panic was engulfing my entire being. What was being prepared there, behind the heavy iron door? What new atrocity did Caraffa invent this time?.. Unfortunately, I didn’t have to wait long - they came for me exactly at midnight. A small, dry, elderly priest led me to the already familiar, creepy basement...

And there... suspended high on iron chains, with a spiked ring around his neck, hung my beloved father... Caraffa sat in his constant, huge wooden chair and frowned at what was happening. Turning to me, he looked at me with an empty, absent gaze, and said quite calmly:

- Well, choose, Isidora - either you give me what I ask of you, or your father will go to the stake in the morning... There is no point in torturing him. Therefore, decide. Everything depends on you.

The ground disappeared from under my feet!... I had to use all my remaining strength so as not to fall right in front of Caraffa. Everything turned out to be extremely simple - he decided that my father would no longer live... And this was not subject to appeal... There was no one to intercede, no one to ask for protection. There was no one to help us... The word of this man was a law that no one dared to resist. Well, those who could, they just didn’t want to...

Never in my life have I felt so helpless and worthless!.. I could not save my father. Otherwise, I would have betrayed what we lived for... And he would never forgive me for that. The worst thing that remained was to simply watch, without doing anything, as the “holy” monster called the Pope cold-bloodedly sent my good father straight to the stake...

Father was silent... Looking straight into his kind, warm eyes, I asked him for forgiveness... For the fact that I had not yet been able to fulfill my promise... For the fact that he suffered... For the fact that I could not to save... And for the fact that she herself was still alive...

- I will destroy him, father! I promise you! Otherwise, we will all die in vain. I will destroy him, no matter the cost. I believe in it. Even if no one else believes in it... – I mentally swore to him with my life that I would destroy the monster.

The father was unspeakably sad, but still stoic and proud, and only in his affectionate gray eyes a deep, unspoken melancholy nested... Tied in heavy chains, he was not even able to hug me goodbye. But there was no point in asking Caraffa about this - he probably wouldn’t allow it. The feelings of kinship and love were unfamiliar to him... Not even the purest love of humanity. He simply did not recognize them.

- Go away, daughter! Go away, dear... You will not kill this non-human. You'll just die in vain. Go away, my heart... I will wait for you there, in another life. The North will take care of you. Go away, daughter!..

– I love you so much, father!.. I love you so much!..

Tears choked me, but my heart was silent. I had to hold on - and I held on. It seemed that the whole world had turned into a millstone of pain. But for some reason she didn’t touch me, as if I was already dead...

- Sorry, father, but I will stay. I will try as long as I live. And I won’t even leave him dead until I take him with me... Forgive me.