Among the ancient Hellenes, Claudius Ptolemy was an outstanding personality. Interesting facts from the life of this scientist testify to his great mind and abilities in a wide variety of sciences. Astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, geographer. In addition to these sciences, he studied music, studied vision and dealt with issues of demography.

Who is Claudius Ptolemy?

Almost nothing is known about the life of this ancient Greek scientist. His biography remains a mystery to historians. No sources have yet been found that mention Ptolemy; interesting facts from the life of this man have been lost.

The place and date of his birth, what family he belonged to, whether he was married, whether he had children - nothing is known about this. We only know that he lived from about the 90s to 170 AD, became famous after 130 AD, was a Roman citizen, lived for a long time in Alexandria (from 127 to 151 AD), where was studying

The question of what family Ptolemy belonged to causes a lot of controversy among scientists. Interesting facts from the life of the scientist speak in favor of the fact that he was a descendant of the royal family of the Ptolemies. However, this version does not have sufficient evidence.

The works of the scientist, which have survived to this day

Many scientific works of this ancient Greek have reached our time. They have become the main sources for historians studying his life.

"The Great Collection" or "Almagest" is the main work of the scientist. This monumental work of 13 books can rightfully be called an encyclopedia of ancient astronomy. It also has chapters on mathematics, namely trigonometry.

"Optics" - 5 books, on the pages of which the theory about the nature of vision, about the refraction of rays and visual illusions, about the properties of light, about flat and convex mirrors is outlined. The laws of reflection are also described there.

"The Doctrine of Harmony" - work in 3 books. Unfortunately, the original has not survived to this day. We can only look at the abridged Arabic translation, from which the Harmonica was later translated into Latin.

“The Quadruple” is a work on demography, which sets out Ptalomey’s observations about life expectancy and gives a division of age categories.

"Handy Tables" - a chronology of the reign of the Roman emperors, Macedonian, Persian, Babylonian and Assyrian kings from 747 BC. until the period of the life of Claudius himself. This work has become very important for historians. The accuracy of her data is indirectly confirmed by other sources.

"Tetrabiblos" - a treatise dedicated to astrology, describes the movement celestial bodies, their influence on the weather and on humans.

"Geography" is a collection of geographical information from antiquity in 8 books.

Lost Works

Ptolemy was a great scientist. Interesting facts from his books became the main source of astronomical knowledge right up to Copernicus. Unfortunately, some of his works have been lost.

Geometry - at least 2 essays were written in this area, traces of which could not be found.

Works on mechanics also existed. According to the 10th century Byzantine Encyclopedia, Ptolemy is the author of 3 books in this field of science. None of them have survived to this day.

Claudius Ptolemy: interesting facts from life

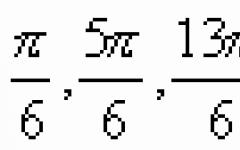

The scientist compiled a table of chords; it was he who first used the division of degrees into minutes and seconds.

The laws he described are very close to the modern conclusions of scientists.

Claudius Ptolemy is the author of many reference books, which was new in those days. He summarized the works of Hipparchus, the greatest astronomer of antiquity, and compiled a star catalog based on his observations. His works on geography can also be represented as a specific reference book, in which he summarized all the knowledge available at that time.

It was Ptolemy who invented the astrolabon, which became the prototype of the ancient astrolabe - an instrument for measuring latitude.

Other interesting facts about Ptolemy - he was the first to give instructions on how to draw a world map on a sphere. Without a doubt, his work became the basis for the creation of the globe.

Many modern historians emphasize that it is a stretch to call Ptolemy a scientist. Of course, he made several important discoveries of his own, but most of his works are clear and competent presentations of the discoveries and observations of other scientists. He did a titanic job of collecting all the data together, analyzing and making his own corrections. Ptolemy himself never put his authorship under his writings.

Claudius Ptolemy lived in Alexandria in 150 AD. This great scientist of antiquity was diversified and had a great influence on the development of many sciences. Its the most famous works that have survived to this day:

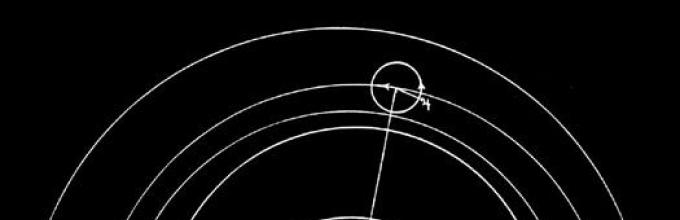

1. Astronomy: Ptolemy’s Almagest is one of the most important works in ancient astronomy. An interesting fact: he described the geocentric model of the universe. The movement of the Sun, Moon and planets around the Earth is described. It also contains a catalog of stars with their brightness on a logarithmic scale. The work was published in 13 volumes.

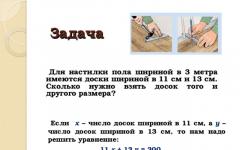

2. Geography: Ptolemy described the world geography of those times in his book called Geography. The maps given by Ptolemy covered 180 degrees of longitude from the Canary Islands to China, and 80 degrees of latitude from the Arctic to the East Indies.

3. Astrology: Ptolemy's treatise on astrology is known as the Tetrobible. The book greatly influenced the practical development of astrology. Ptolemy rejected methods that had no logical basis and also believed that astrology was not an absolutely reliable science. There were four books in this treatise.

2nd version:

Neither the place nor the time of birth of Ptolemy is known, an astronomer who for many centuries enjoyed such respect that numerous admirers called him divine. All that can be considered true is that he lived under Hadrian and Antoninus, became famous in 130 AD, and died after 22 March 165 AD.

The details of his biography are also unknown, but there are interesting facts. Some writers, based on the similarity of names, argued that he belonged to the royal family of the Ptolemies, but hid the celebrity of his origin, wanted to become famous for his learning and therefore spent his whole life contemplating the sky, observing it in one of the branches of the Egyptian temple at Canopus. Ptolemy modestly called his main work “Mathematical collection or syntax.” Arabic translators turned it into a “great creation” and this name (Almagest) remained with him forever.

The Almagest enjoyed such great respect in the East that the victorious caliphs, concluding peace with the Byzantine emperors, demanded copies of Ptolemy's creations.

In the Almagest, Ptolemy clearly outlined his system of the world, with many questions related to it; it also contains descriptions of the projectiles that Ptolemy considered necessary for accurate observations.

If an astronomer now wants to study the Almagest in detail, not only for historical knowledge, but also to extract data from it for his research, then the glory of Ptolemy will seem doubtful to him. Kepler, seeing how difficult it was to reconcile Ptolemy’s conclusions with the latest observations, did not want to encroach on the celebrity of the Alexandrian astronomer and suggested that significant changes had occurred in the sky over the course of fifteen centuries. But Clay, Lemonnier, Lalande and Delambre were not so lenient: they accused Ptolemy of falsifying the ancient observations of Hipparchus, of appropriating some of them and of concealing those that did not agree with his theory. From this, disputes arose between first-class scientists, which ended with the fact that the ancient glory of Ptolemy was greatly diminished and the primacy was given to the old Hipparchus. Other works of Ptolemy have come down to us only in Arabic translations. Of these, we will mention here only his “optics,” the Latin translations of which are kept in the Paris library and, it seems, in one library in Italy. This book contains a table of the refractions of light when passing from air to water and glass, therefore Ptolemy’s optics is the only work from which it is clear that the ancient Greeks were engaged in physical experiments. Here we find precise concepts about the refraction of light in the atmosphere: the magnitude of refraction is not correct, but Ptolemy correctly knew that the refraction of light increases from the zenith to the horizon, and at the zenith light does not change its direction.

3rd version:

Ptolemy Claudius (c. 90 – c. 168), ancient Greek astronomer, geographer, mathematician. The author of the treatise “Guide to Geography” in 8 books, in which he defined science, examined its subject and methods, significantly expanded and corrected the ideas about the Earth that existed before him, proposed new cartographic projections, laid the foundations of regional geography, and also listed o.c. 8000 cities and localities with their indication geographical coordinates. The treatise was accompanied by one general and 26 special maps of the earth's surface. Discovered in the Middle Ages, it served as a foundation for a long time. source of geographical information. Other fundamental work of Ptolemy – « Great mathematical construction astronomy in 13 books", or "Almagest". It establishes the geocentric system of the world. About the life of Ptolemy very little is known. It is believed that he was born in Ptolemand of Egypt and spent most of his life in Alexandria, where he studied manuscripts in the famous library.

Geography. Modern illustrated encyclopedia. - M.: Rosman. Edited by prof. A. P. Gorkina. 2006.

Ptolemy Claudius (in Latin Claudius Ptolemaeus) (flourished 127–148), famous astronomer and geographer of antiquity, through whose efforts the geocentric system of the universe (often called Ptolemaic) acquired its final form. Nothing is known about the origin, place and dates of birth and death of Ptolemy. Dates 127–148 are derived from observations made by Ptolemy in and around Alexandria. His star catalogue, which is part of the astronomical work Almagest, is dated 137. All others information about the life of Ptolemy come from later sources and are rather doubtful. It is stated that he was still alive during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180), and died at the age of 79. From this we can conclude that he was born at the end of the 1st century. The most famous works of Ptolemy are Almagest and Geography, which became the highest achievement of ancient science in the field of astronomy and geography. Ptolemy's works were considered so perfect that they dominated science for 1,400 years. During this time, practically no serious amendments were made to Geography, and all the achievements of Arab astronomers were essentially reduced to only minor improvements to the Almagest. Although Ptolemy was the most revered authority in all ancient science, to call him genius mathematician, astronomer or geographer is impossible. His gift was the ability to bring together the results of the research of his predecessors, use them to refine his own observations, and present the whole thing as a logical and complete system, presented in a clear and polished form. The excellent educational and reference works he created made it possible to maintain quite high level knowledge in relevant subjects. It can be said that the modern era scientific research in these areas began with the overthrow of the authority of the Almagest and Geography.

Almagest. The name is a combination of the Arabic definite article and Greek word“megiste”, which means “greatest” (implies “syuntaxis” - system, since the original name of the work is Mathematics syntax, i.e. Mathematical system). This work culminated centuries of efforts by Greek astronomers to explain the complex movements of the stars. It consists of 13 books, which not only describe, but also analyze the entire body of astronomical knowledge of that time. See also astronomy and astrophysics.

Books I and II of the Almagest serve as an introduction, which describes the main astronomical assumptions of Ptolemy and his mathematical methods. He presents his evidence for the sphericity of the Earth and sky, as well as the central position of the Earth in the Universe. Ptolemy believes that the Earth is motionless, and the sky rotates daily around the celestial axis. In Book I there is a table of chords for arcs subtending angles from 1/2 to 180 degrees in increments of 1/2° - the equivalent of a table of sines for half the angles. The idea for the table is taken from the lost work of the Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 190 – after 126 BC); it became the starting point for the further development of trigonometry. Book II contains such methods of mathematical geography as determining the longest day of the year for a point with a given latitude and determining latitudes (“climates”) in the inhabited zones of the Earth based on data on the duration of the longest day in these zones.

Books III and IV discuss the movement of the Sun and Moon. Ptolemy accepts Hipparchus' theory to explain the anomalies solar movement(caused in reality by the ellipticity of the Earth's orbit), using the hypothesis of epicycles and eccentrics. Ptolemy's theory of the revolution of the Moon is much more complex. He suggests that the Moon moves along an epicycle, the center of which moves from west to east along an eccentric deferent. In turn, the center of the deferent revolves around the Earth from east to west, and this entire mechanism lies in the plane of the apparent movement of the Moon. For an observer on Earth, the opposite movements of the center of the epicycle and the deferent cancel each other with respect to the line connecting the Earth and the Sun. Thus, the epicycle is at the apogee of the eccentric at the moments of the new moon and full moon, and at perigee during the first and last quarters. This scheme successfully overcame the main drawback of Hipparchus’ theory of the revolution of the Moon and took into account the periodic “swinging” of the lunar apogee, later called evection, for which Ptolemy obtained an almost correct value.

Book V discusses different topics: the construction of the theory of the revolution of the Moon continues, the design of the astrolabe is described, the sizes of the solar, lunar and earth's shadows, the diameters of the Sun, Moon and Earth, as well as the distance to the Sun are estimated. Book VI is dedicated to solar and lunar eclipses. Books VII and VIII describe the stars by constellation. The latitude and longitude of each star are given in degrees and minutes, and magnitudes are indicated in the range from 1 to 6. It is not entirely clear how much of this catalog was the fruit of Ptolemy’s own observations, and how much was borrowed from Hipparchus, taking into account precession over the past three centuries. The precession of the equinox, the structure of the Milky Way, and the design of the celestial globe are also discussed here.

Books IX–XIII are devoted to the movement of the planets, a problem that Hipparchus left without consideration. Book IX examines the order of the planets (their relative distances from the Earth), their periods of revolution; here the author begins the theory of the revolution of Mercury. Book X is dedicated to Venus and Mars, and Book XI is dedicated to Jupiter and Saturn. Book XII discusses the stationary and retrograde motion of each of the planets, as well as the maximum elongations of Mercury and Venus. Ptolemy's basic diagram represents Venus and the three superior planets as bodies moving from west to east in epicycles, the centers of which move in the same direction along eccentric deferents. It is assumed that the center of the epicycle moves at a constant angular velocity not around the center of its deferent, but around a point lying on a straight line connecting the Earth with the center of the deferent and removed from the Earth by twice the distance between it and the center of the deferent. The epicycles and deferents are inclined to the ecliptic at different angles. Mercury's motion pattern is even more complex.

Geography. In its field of knowledge, Ptolemy's Geography occupied the same place as the Almagest in astronomy. It was believed that this work contained a complete presentation of the subject and was practically infallible, so that until the Renaissance, theoretical geography slavishly followed it. However, as a scientific treatise, Geography is undoubtedly inferior to the Almagest. Although the Almagest is imperfect in the sense of astronomy, it is interesting from the point of view of mathematics. In Geography, achievements in theory coexist with serious omissions in their application. Ptolemy begins with a clear presentation of the methods of cartography - determining the astronomical latitude and longitude of a place and methods of depicting spherical surfaces on a plane. Then he moves on to the main part of his treatise, built on the approximate calculations of sailors and explorers. Although Ptolemy presents his subject matter in mathematical form and the work gives an impressive list of more than 8,000 names of places - cities, islands, mountains, estuaries, etc., it would be wrong to think that this work represents a scientific study. Precisely because theoretical aspects cartography is presented in this book quite satisfactorily even for a modern elementary textbook, we can be sure: Ptolemy knew that in his time the true coordinates of places had not yet been accurately determined.

In Book I of Geography, Ptolemy discusses the reliability of determining the relative positions of points on the Earth by astronomical methods and from measurements of distances on the surface and estimates of the paths taken by travelers. He admits that astronomical methods are more reliable, but points out that for most places there is no data other than travellers' reckoning. Ptolemy considers the most reliable mutual control of ground and astronomical methods. He then gives clear instructions for constructing a map of the world on a sphere (much like a modern globe) as well as on a flat surface using a conic projection or an improved spherical projection. The remaining seven books consist almost entirely of a list of the names of various places and their geographical coordinates.

Since the vast majority of the data was obtained by travelers (collected around 120 AD by Ptolemy's predecessor Marinus of Tire), Ptolemy's atlas contains many errors. The almost correct value of the earth's circumference, calculated by Eratosthenes, was underestimated by Posidonius by more than a quarter, and this underestimated value was used by Ptolemy. Ptolemy's prime meridian passes through the Canary Islands. Due to the exaggerated size of Asia by travelers, it turned out that the world known at that time stretched over more than 180° (actually 130°). At the 180th meridian of his map is China, a giant landmass stretching from the top of the map to the equator. It followed that the unknown part of the Asian continent stretches even further, to where it is now depicted Pacific Ocean. This was Ptolemy’s classic idea, preserved for centuries, of the Earth as a sphere reduced by a quarter compared to its actual size and covered with land, occupying 2/3 of the Northern Hemisphere. It was this that inspired Christopher Columbus with the confidence that India needed to be reached by moving westward. Ptolemy accompanied his work with an atlas of 27 maps: 10 regional maps of Europe, 4 maps of Africa, 12 maps of Asia and a summary map of the entire world known by that time. The book gained such authority that even a century after the voyages of Christopher Columbus and Magellan, which overthrew the basic principles of Geography, maps in the Ptolemaic style were still being published. Some of his erroneous ideas were persistently repeated on maps of the 17th and 18th centuries, and as for interior Africa, his map was printed even in the 19th century.

Other works. Ptolemy's versatility and his amazing gift for clear and concise presentation were also evident in other treatises, for example on optics and music. The work on optics survives only in a Latin translation from Arabic - also a translation from a lost Greek original. It consisted of five books, of which Book I and the end of Book V have been lost. Books III and IV are devoted to the reflection of light. Ptolemy resorted to measurements to prove that the angle of incidence was equal to the angle of reflection. Book V is about the refraction of light. It describes experiments on refraction in water and glass at various angles of incidence and makes an attempt to apply these results in astronomy to estimate the degree of refraction of light coming from a star through the earth's atmosphere. Ptolemy's treatise is the most complete work on mirrors and optics preserved from ancient times.

Ptolemy's Harmonics has gained the reputation of being the most scientific and well-composed treatise on the theory of musical modes that has survived in Greek. This is the second most important treatise on ancient music, after the works of Aristoxenus (second half of the 4th century BC). However, Ptolemy's work has more practical orientation. Among Ptolemy's other works is a treatise on astrology, Apotelesmatics, in four books, usually called Tetrabiblos. This work was as authoritative in its field as the Almagest in its.

INFLUENCE OF PTOLEMY'S THEORY

Ptolemy's works reigned supreme in science for almost 1,400 years, but his influence on social, political, moral and theological views was even more lasting and lasted until the revolution of the 18th century. Ptolemy's theory of an anthropocentric Earth located in a geocentric Universe became widespread, especially through medieval encyclopedias. The reconciliation of Christian doctrine with the ancient heritage carried out by Albertus Magnus (c. 1193–1280) and Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) made the teachings of the ancients acceptable and useful for the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The study of the Universe has led to a revision of man's relationship with the world around him. The order of the planets established by Ptolemy and his assumption of the influence of each of them on a certain group of people were interpreted by the church as part of a great hierarchy, or chain, of being. The highest link in this chain were God and the angels, followed by man, woman, animals, plants and, finally, minerals. This doctrine, together with the story from the Book of Genesis about the creation of the world in 6 days, was the main background of all European poetry and prose from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. It was believed that the great chain of being has divine origin and defines division feudal society into three estates - the nobility, the clergy and the third estate, each of which plays its own role in the life of society. This view was so firmly rooted in society that Galileo, who defended the heliocentric theory of Copernicus, was put on trial by the Inquisition in Rome in 1616 and forced to renounce his views.

Evidence of Ptolemy's influence on literature is countless. Some authors directly point to Ptolemy as the highest authority. Others, like Dante and Milton, make Ptolemy's universe the basis for constructing their own worlds. In Chaucer's works there are references to the Almagest and there are references to the works of Ptolemy.

The concept of cosmic order permeates all of E. Spencer’s work; for him, all beings are “arranged in the correct row.” Elizabethan authors spoke about the need for order and multi-levelness in the chain of being and about the influence of the stars on life as an instrument of divine Providence. Shakespeare's heroes live in the world of Ptolemy. In canto 8 of Milton's Paradise Lost, Adam expresses doubt about the Ptolemaic system, and the archangel Raphael, dissuading him, speaks not so much about its truth, but about its greater rationality and suitability for human existence in comparison with the heliocentric one. Back in the 18th century. Pope's Experience about a person exclaims: “O shining chain of existence!”, which is indispensable for the Universe, since otherwise “The planets with the Sun will be drawn at random,” and a person will be immersed in “delusion without end.”

LITERATURE

Bronshten V.A. Claudius Ptolemy. M., 1988

Claudius Ptolemy. Almagest. M., 1998

Encyclopedia Around the World. 2008.

It was believed that Hyperborea was located behind the Riphean Mountains, this is how these Riphean Mountains were approximately imagined, it is interesting that the Baltic Sea is called the Sarmatian Ocean.

Claudius Ptolemy and his forgotten maps of the North

V. N. Tatishchev very highly appreciated the merits of the famous geographer, astronomer, geometer and physicist of antiquity Claudius Ptolemy (about 90–168), and from his books he especially singled out the fundamental work “Guide to Geography” 74:

“Claudius Ptolemy is the first among respectable geographers, for although before him there were very many geographical descriptors, as Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny are stated above, and they mention a great number of writers, of which very few books remain for us, but this one can therefore be honored as the first that he laid down the first system of the world."

Tatishchev V.N. Russian history from ancient times. T. 1.

An important appendix to his “Manual of Geography” were the so-called land maps, oriented north up for the first time. It is known that before Ptolemy, most maps were oriented south, less often east.

The fate of this work is interesting. Soon after its appearance, this work of Ptolemy was undeservedly forgotten for almost thirteen centuries, or rather, until the Renaissance. It was not until 1409 that Manuel Chrysoporus translated it into Latin. Since then, the “Guide to Geography” has been reprinted dozens of times, and due to the huge number of maps (more than 60), the name of Ptolemy has become a household name: all collections of maps, which we call atlases, were called Ptolemies in the Middle Ages.

Of course, of particular interest to us is the 3rd book, where Ptolemy gives a description of Sarmatia, which he locates between the Vistula (Vistula) and Ra (Volga) rivers, simultaneously dividing it into European and Asian parts. Above Sarmatia, he points out, there are lands unknown to him, so we will not find descriptions of them in the book. According to V.N. Tatishchev, under unknown land it is necessary " to mean Siberia, Herodotus calls Iperborea" 75. Following Tatishchev, we could add: ... and the North of modern Europe.

Speaking about the population of Sarmatia, Ptolemy, like Tacitus, points to the Finns, classifying them not as the main ones, such as the Wends (it is believed that these are the ancestors of the Slavs), Roksolans, Yazigis and Scythian Alans, and to " less important tribes" 76 .

"The less significant tribes inhabiting Sarmatia are the following: near the Vistula River, below the Wends - the Giphons (Gitons), then the Finns; then the Sulans (Bulans), below them - the Frugdions, then the Avarins (Obarins) near the sources of the Vistula River."

Along the coast of the Venedian Gulf (southern part of the Baltic Sea), above or north of all, according to Ptolemy, lived unknown tribes - the Carboniferous, and to the east of them - the Karests (future Karelians?) and Sals. Just below them lived the already mentioned gelons, melanchlenes and the Boruskas, unfamiliar to us, distributed as far as the Burdock Mountains themselves 77.

“Then the ocean coast near the Gulf of Venedia is occupied by the Velts, above them the Ossia, then the northernmost - the Carboniferous, to the east of them - the Karests and Sals (below these are the Gelons, Hippods and Melanchlens); below them are the Agathyrs, then the Aorsi and Pagyrites; below them - Savars and Boruski to the Riphean Mountains."

Ptolemy K. Guide to Geography.

As for the territory of Sarmatia, bordering on the unknown northern land, it belongs, Ptolemy points out, Sarmatians - Hyperboreans 78 .

Surprisingly, for some reason Ptolemy ignored Scandinavia and the Swions, but on his map three small islands appear near the Cimbri (now Jutland) peninsula and one larger island - all of them were called Scandia.

Part 1. “The Fall of the Ancient World.”

In the posts of this blog it was discussed large number“ancient” material known to us: star celestial atlases and geographical maps. We can say unequivocally that “available” are mainly those materials on which the Scaligerian history is based and modern astronomy and geography. Almost everything that contradicts officialdom has been “cleaned and erased” from the history of the evolution of our planet.

However, in the works of this blog, the facts of many inconsistencies in these “ancient” stellar, geographical maps, tables of observations of celestial events, the same scientific world history.

Let's remember that almost all the information about the knowledge of the “ancient” Greeks about the stars is known today from two works that have come down to us: “ Commentary on Aratus and Eudoxus", written Hipparchus And " Almagest" Ptolemy.

It is believed that astronomy began to take shape as an exact science thanks to the works of the “ancient” Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who allegedly lived around 185-125 BC.

The Scaligerian version in the 18th century, dating the Almagest around the 2nd century AD, was initially considered indisputable. However, in the 19th century, after a more thorough analysis of the longitudes of the stars in the Almagest, it was noticed that, in terms of precession, these longitudes were more consistent with the era of the 2nd century BC, that is, the era of Hipparchus. How were these statements calculated and verified? It turns out that based on the so-called Precession of the Earth's axis!

()- April 25th, 2019 , 01:55 am

Part 9.

Where was the Dragon looking?

Continuation

Presented at the junction of eras New celestial atlas.

Christian Friedrich Goldbach ( Christian Friedrich Goldbach, 1763 - 1811) - German astronomer and cartographer... In 1804, Goldbach in Moscow became the first full professor of astronomy at Moscow University.

IN 1799 Christian Goldbach published the New Celestial Atlas (Neuster) in Weimar Himmels-Atlas), with fairly accurate copies of Flamsteed's constellations. Its peculiarity was not only the negative (white on black) image: a similar technique was used by Semler in the atlas of 1731. Goldbach made each card in two versions:

a) only stars (without grid and figures) and

b) traditionally - with superimposed images of constellations.

Fig 1. 1799 Goldbach_W_01. Northern Hemisphere.

This planisphere does not indicate an equatorial coordinate grid, although the planisphere itself is made along the equatorial boundary.

In general, the maps - planispheres (previously discussed) of Jamison 1822, Bode 1782-1805 and Goldbach 1799 are almost identical.

- February 24th, 2019 , 08:29 pm

Part 5. Rotation of the Sun.

We all know for sure, and not only from astronomy textbooks, we have long and persistently been taught that the Earth revolves around the Sun strictly in a certain orbit. Based on this, natural questions arise regarding the Sun itself: does it rotate? And if so, around what? Does the Sun rotate around its axis?

How does official science answer these questions?

Rice

1. Cellarius_Harmonia_Macrocosmica-Tychonis_Brahe_Calculus

About the concept " Sun"You can read a lot on Wikipedia: about its structure, atmosphere, magnetic fields, about the study of the sun and its eclipses, about its significance in religion and occultism, about its doubles and even about solar neutrinos. What else do you need? But how does it rotate and does it rotate at all?

If you type “Rotation of the Sun” into the search engine, Wikipedia for some reason comes up with a precipitate, talks about the rotation of the Earth around the Sun (well, stupid “me”), and invites me to create such a topic myself...

Still, the Sun rotates around its axis, scientists come to this conclusion.

Interesting, How are studies of the rotation of a star carried out?

()

- January 15th, 2018 , 03:25 pm

Part 4.

Dating of Star Catalogs.

A brief excursion into the history of astronomy in the light of NH.

What star catalogs do we know?

It is believed that Almagest star catalog- this is the oldest detailed astronomical work that has come down to us.

The Scaligerian dating of the Almagest is approximately the 2nd century AD.

According to the same dating - earlier than the 10th century AD. no other star catalogs other than the Almagest catalog are known.

Only in the 10th century was the first medieval catalog of stars created by the Arab astronomer Abdul-al-Raman ben Omar ben-Muhammad ben-Sala Abdul-Husayn al-Sufi (full name) in Baghdad, allegedly in the years 903-986.

However, upon closer examination it turns out that this is the same Almagest catalogue. But if in the lists and editions of the Almagest that have come down to us, the star catalog is given by precession, as a rule, to about 100 AD, then Al Sufi catalog- the same catalogue, but given by precession to the 10th century AD. This fact is well known to astronomers. Bringing a directory to an arbitrary desired one historical era was done using the simplest arithmetic operation - by adding a certain constant value to the longitudes of all the stars, described in detail in the Almagest itself.

The next, according to the Scaliger-Petavius chronology, is considered Ulugbek catalog(supposedly 1394-1449 AD, Samarkand).

All three of these catalogs are not very accurate , since the coordinates of the stars are indicated in them on a scale in increments of about 10 arc minutes.

The next catalog that has come down to us is the famous Tycho Brahe catalog(allegedly 1546-1601), the accuracy of which is already significantly better than the accuracy of the three listed catalogs. Brahe's catalog is considered the pinnacle of mastery achieved using medieval observational techniques and instruments.

When was Ptolemy's Almagest written?

"Most of the manuscripts on which our knowledge of Greek science is based are Byzantine copies, produced 500-1500 years AFTER THE DEATH OF THEIR AUTHORS." (O. Neugebaier "Exact Sciences in Antiquity")

Ptolemy, together with Hipparchus (supposedly 2nd century AD), is considered the founder of astronomical science, and his “Almagest” (Great Creation) is an immortal monument of ancient science.

()

- December 6th, 2017 , 03:25 pm

Part 3.

Almagest of Ptolemy. Where is his reference point button?

Information about the knowledge of the “ancient Greeks” about the stars is found today in two works that have come down to us: “Commentary on Aratus and Eudoxus,” written allegedly by Hipparchus around 135 BC, and “Almagest” by Ptolemy.

« Almagest"(lat. Almagest, from Arabic. الكتاب المجسطي, al-kitabu-l-mijisti — « Great formation" The great mathematical construction of astronomy is presented in 13 books, the full volume of which is 430 pages of a large-format modern edition. This is a classic work that appeared around the year 140 (according to the Scaligerian chronology - CX) and includes the full range of astronomical knowledge of Greece and the Middle East at that time.

The Almagest is believed to have been written by the Alexandrian astronomer, mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy or Ptolemy. Historians date his activities to the 2nd century AD. According to historians of astronomy, “history has dealt with the personality and works of Ptolemy in a rather strange way. There is no mention of his life and work by historians of the era when he lived... Even the approximate dates of Ptolemy’s birth and death are unknown, just as any facts of his biography are unknown.” .

Ptolemy's star catalog is contained in his 7th and 8th books of the Almagest. There is the so-called canonical edition of the Almagest star catalog, made by Peters and Knobel, and two complete editions of the Almagest in translations by R. Catesby Taliaferro and Toomer.

The Russian translation of the Almagest first came out of print only in 1998 in a very limited edition of one thousand copies (excerpts below will be from this publication).

In Scaligerian chronology (SC), it is believed that the Almagest was created during the reign of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius, who ruled in 138 - 161 AD.

It is worth immediately noting that the very literary style of this book, very verbose and flowery in places, rather speaks of the Renaissance than of deep antiquity, when paper, parchment, and even more so a book, were precious objects.

From the very beginning of acquaintance with the Almagest, it is noticeable that Ptolemy’s work is dedicated to the Sir, that is, the King. For some reason, historians are very surprised what kind of Tsar we are talking about here. A modern commentary goes like this: " This name (i.e. Sir = King) was quite common in Hellenistic Egypt during the period under review. There is no other information about this person. It is not even known whether he studied astronomy."

This book ends in a remarkable way. Here is its epilogue.

"After we have done all this, O Sir, and have examined, as I think, almost everything that should be considered in such a work, how much has the time that has passed so far contributed to increasing the accuracy of our discoveries or clarification, carried out not for the sake of boasting, but just for the sake of scientific benefit, let our present work receive a suitable and proportionate end here" (p.428).

However, the fact that the Almagest was associated with the name of a certain King is confirmed by the following circumstance. It turns out that in late antiquity and the Middle Ages Ptolemy was also credited with royal origin. In addition, the name Ptolemy or Ptolemy itself is considered a generic name Egyptian kings who ruled Egypt after Alexander the Great.

However, according to SH, the Ptolemaic kings left the scene around 30 BC. That is, more than a century before the astronomer Ptolemy. Thus, only SH prevents us from identifying the era of the Ptolemaic kings with the era of the astronomer Ptolemy = Ptolemy. Apparently, in the Middle Ages, when CX had not yet been invented, the Almagest was attributed specifically to the Ptolemy kings. Rather, not as authors, but as organizers or customers of this fundamental astronomical work. That is why the Almagest was canonized and became an indisputable authority for a long time. Then it becomes clear why the book begins and ends with a dedication to the King = Sir. It was, so to speak, the royal textbook on astronomy.

The question is, when did this all happen?

The Almagest contains a detailed presentation of the geocentric system of the world, according to which the Earth rests at the center of the universe, and all celestial bodies revolve around it.

()

()

- November 27th, 2017 , 05:20 pm

Part 2.

Maps of Ptolemy's Geography.

More from school years We remember that the famous work of the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus “On the Rotations of the Celestial Spheres” was banned by the Inquisition. In 1616 it was added to the Roman list of prohibited books. Copernicus created a heliocentric system for the structure of the Universe and, in fact, rejected the geocentric system, which was adhered to by Claudius Ptolemy, in favor of predicting the movement of planets based on the hypothesis of their revolution around the Sun. The works of heliocentrists were finally excluded from the index of banned books only in 1835.

We are accustomed to the fact that Copernicus (rival), whom catholic church, in fact, posthumously declared a heretic, was “good”, and his predecessor Ptolemy, by contrast, appears as a dense ignoramus and a brake on the progress of science. Meanwhile, the prominent father of the church and outstanding fighter against heresies, St. Epiphanius of Cyprus, without hesitation, considered Ptolemy himself and his followers to be heretics because they claimed the possibility of predicting the movement of planets using mathematical calculations. In his work “Panarion”, dedicated to the exposure of 80 heresies, Epiphanius writes:

The successor of Secundus and the named Epiphanes, who adopted the Exhortation from Isidore as the basis of their opinions, is Ptolemy, who belongs to the heresy of the same so-called Gnostics and followers of Valentinus with some others, but who also added something different in comparison with his teachers. Boasting of his name, and those who trusted him are also called Ptolemies (Πτολεμαῖοι)...

Having defined the basic concepts in the previous part, let’s return to “Geography” by Claudius Ptolemy and try to find out in what way, technically, the information was collected.

The main drawback of the heterogeneous, multilingual translations of the “Geography” of Claudius Ptolemy (Ptolemy) that have come down to us is the absence of truly ancient maps illustrating the “Geography” itself, or their copies. Scientists began a full comparison of translations of “Geography” only at the beginning of the 20th century. A comprehensive study of Ptolemy's Geography is Paul Schnabel's book (Schnabel, 1939). In different editions of his great work, sometimes maps were also inserted (allegedly from the 13th century onwards). The maps closest to the original are from the publishing house Dover Publication Inc, N-Y, E. L. Stevenson (published in 1932) - maps of N. Donnus from the Codex Ebnerianus manuscript, traditionally dated to the second half of the 15th century. This is directly the placement of points from the Geography, in the conical projection named after Donnus and used in printed publications since the late 15th century. Total points with coordinates settlements, capes, mountains, lakes, mouths and river sources there are a little more than 8000. Some of the first illustrations to “Geography” are attributed to a certain “mechanic” Agathodemon, who allegedly created a map of the world by 180 and added it to the work of Ptolemy.

One of the sheets of the Donnus map (c. 1460), depicting Africa.

Claudius Ptolemy (They hide, swim forward, backward

And sometimes they stop.

What if the seventh in their row

Is the Earth a planet?

Claudius Ptolemy(ancient Greek Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖ ος, lat. Claudius Ptolemaeus,).

From Wikipedia we know that this Ptolemy is a late Hellenistic astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, mechanic, optician, music theorist and geographer. Lived and worked in Alexandria of Egypt (allegedly in the period 127-151), where he conducted astronomical observations.

He is the author of the classic ancient monograph “Almagest”, which was the result of the development of ancient celestial mechanics and contained practically full meeting astronomical knowledge of Greece and the Middle East at that time. He left a deep mark in astrology.

There is no mention of his life and work in contemporary authors. In historical works of the first centuries AD, Claudius Ptolemy was sometimes associated with the Ptolemaic dynasty, but modern historians believe this to be an error due to the coincidence of names. The Roman nomen (family name) Claudius shows that Ptolemy was a Roman citizen, and his ancestors received Roman citizenship, most likely from the Emperor Claudius.

Ptolemy’s main work was “The Great Mathematical Construction of Astronomy in Thirteen Books,” which was an encyclopedia of astronomical and mathematical knowledge of the ancient Greek world. On the way from the Greeks to medieval Europe through the Arabs the name "Megale syntaxis" ("Great formation") transformed into "Almagest".

Initially, Ptolemy’s work was called “Mathematical collection in 13 books” (Ancient Greek: Μαθηματικικης Συντάξεώς βιβλἱ α ιγ). In late antiquity this work was referred to as “ The Greatest Essay" When transferring to Arabic word“greatest” (ancient Greek μεγίστη, magiste) became " al-majisti" (Arabic: المجسطي), which in turn was translated into Latin as " Almagest"(lat. Almagest), which became the generally accepted name.

Another important work of Ptolemy, the Guide to Geography in eight books, is a collection of knowledge about the geography of everything known to the ancient peoples of the world. In his treatise, Ptolemy laid the foundations of mathematical geography and cartography. Published the coordinates of eight thousand points from Scandinavia to Egypt and from the Atlantic to Indochina; this is a list of cities and rivers indicating them geographic longitude and latitude.

It is believed that, based on extensive and carefully collected information, Claudius Ptolemy also completed 27 maps of the earth's surface, which have not yet been discovered and may be lost forever. Ptolemaic maps became known only from later descriptions (Borisovskaya N.A. Ancient engraved maps and plans. - Moscow: Galaxy, 1992. - 272 pp. - P. 7-8.).

Despite the inaccuracy of this information and maps, which were compiled mainly from the stories of travelers, they were the first to show the vastness of the inhabited areas of the Earth and their connections with each other.

About the ancient "space".

Some school and church misconceptions about the ignorance of the ancient “scientists” about the earthly and celestial sphere, about the representation of the “ancients”, about the images of the earth and sky on ancient engravings (maps).

Firstly, there is a widespread misconception that the ancients saw the earth as flat, with three elephants on a turtle swimming on a vast ocean, or in the form of a casket with holes drilled in the lid to represent stars. There are frequent references to the publication of similar books from the Topography of Kozma Indikoplovst and others. However, there are no substantiated statements about a flat earth, neither in the Bible and church books, nor on icons and frescoes. On the contrary, in the most ancient paintings and icons we can see some kind of king or baby Jesus, with an orb in his hand. This power is a model of a globe divided into three parts of the world known from time immemorial: Europe, Asia (Asia) and Ethiopia (Africa). The cross above it means that these are all Christian countries.

()

The works of the scientist, which have survived to this day

Many scientific works of this ancient Greek have reached our time. They have become the main sources for historians studying his life.

"The Great Collection" or "Almagest" is the main work of the scientist. This monumental work of 13 books can rightfully be called an encyclopedia of ancient astronomy. It also has chapters on mathematics, namely trigonometry.

"Optics" - 5 books, on the pages of which the theory about the nature of vision, about the refraction of rays and visual illusions, about the properties of light, about flat and convex mirrors is outlined. The laws of reflection are also described there.

"The Doctrine of Harmony" - work in 3 books. Unfortunately, the original has not survived to this day. We can only look at the abridged Arabic translation, from which the Harmonica was later translated into Latin.

“The Quadruple” is a work on demography, which sets out Ptalomey’s observations about life expectancy and gives a division of age categories.

"Handy Tables" - a chronology of the reign of the Roman emperors, Macedonian, Persian, Babylonian and Assyrian kings from 747 BC. until the period of the life of Claudius himself. This work has become very important for historians. The accuracy of her data is indirectly confirmed by other sources.

"Tetrabiblos" - a treatise dedicated to astrology, describes the movement of celestial bodies, their influence on the weather and on humans.

"Geography" is a collection of geographical information from antiquity in 8 books.

Lost Works

Ptolemy was a great scientist. Interesting facts from his books became the main source of astronomical knowledge right up to Copernicus. Unfortunately, some of his works have been lost.

Geometry - at least 2 essays were written in this area, traces of which could not be found.

Works on mechanics also existed. According to the 10th century Byzantine Encyclopedia, Ptolemy is the author of 3 books in this field of science. None of them have survived to this day.

Claudius Ptolemy: interesting facts from life

The scientist compiled a table of chords; it was he who first used the division of degrees into minutes and seconds.

The laws of light refraction he described are very close to the modern conclusions of scientists.

Claudius Ptolemy is the author of many reference books, which was new in those days. He summarized the works of Hipparchus, the greatest astronomer of antiquity, and compiled a star catalog based on his observations. His works on geography can also be represented as a specific reference book, in which he summarized all the knowledge available at that time.

It was Ptolemy who invented the astrolabon, which became the prototype of the ancient astrolabe - an instrument for measuring latitude.

Other interesting facts about Ptolemy - he was the first to give instructions on how to draw a world map on a sphere. Without a doubt, his work became the basis for the creation of the globe.

Many modern historians emphasize that it is a stretch to call Ptolemy a scientist. Of course, he made several important discoveries of his own, but most of his works are clear and competent presentations of the discoveries and observations of other scientists. He did a titanic job of collecting all the data together, analyzing and making his own corrections. Ptolemy himself never put his authorship under his writings.

Biography of Claudius Ptolemy - scientist from Ancient Greece, which with the help exact science mathematicians developed a scientific theory of the movement of celestial bodies around our Earth. Ptolemy lived and worked in Alexandria of Egypt in the period 127-151. Our planet Earth was considered motionless in the minds of ancient scientists. This theory and the theory of the movement of the only natural satellite of the Earth - the Moon and the luminary - the Sun, were part of the Ptolemaic system of the world.

A significant role in the world history of the development of sciences, the primacy undoubtedly belongs to Claudius Ptolemy. The scientific works of the mysterious scientist greatly influenced the formation of mysterious astronomy and naturally - mathematical sciences. belong to Claudius Ptolemy outstanding works on the main scientific trends of ancient natural science.

"Almagest"

The most famous of them is a scientific work that influenced the development and promotion of the science of astronomy, called by specialists “Almagest”.

In ancient times, the Almagest was equated to the Bible; it describes all the main paths in science. Ptolemy's scientific work was originally titled "Mathematical Work in 13 Books." The Almagest contains thirteen books. The author himself divided the creation into books, and the division into chapters occurred much later. "Almagest" plays the role of a textbook on the theory of astronomy. It is intended for an already formed reader who is familiar with the works of Euclid, spherics and logistics. Theory of planetary motion solar system, described in the Almagest, is the scientific “child” of Ptolemy himself. Over the centuries, with changes in the views of contemporaries scientific work Ptolemy, took first position in the ancient world of science. The great uniqueness of the creation ensured longevity and respect from pundits. For many centuries, the promising “Almagest” was an ideal example of a purely scientific approach to performing all kinds of difficult tasks in astronomy. Without it, it is impossible to imagine the history of the development of the science of stars - astronomy in Persia, India, Arab countries and the old woman - Europe in the Middle Ages.

The famous work of Copernicus “On Rotations,” which became the basis of modern astronomy, its foundation and stronghold, was in many ways a continuation of the “Almagest.” Claudius paid much attention to issues of astronomy; after the Almagest, he wrote many other scientific works.

"Planetary Hypotheses"

In “Planetary Hypotheses,” Claudius presented an undeniable theory of the movement of planetary bodies as a single living organism within the boundaries of the geocentric world system he adopted. “Planetary Hypotheses” is a small work, but it is of great importance in the history of the development of astronomy. It consists of two books. The work is dedicated full description astronomical system as a single living organism.

"Tables at hand" and "Quadrbooks"

He created “Tables at Hand” with instructions that are used by astronomers to this day.

An amazing treatise where Claudius Ptolemy revealed astronomical and astrological scientific issues. The treatise made it possible to open the door to the depths of understanding and creation of the Universe. "Handy tables" are greatest book of its time. This work by the author consists of many tables that are designed to accurately find the positions of celestial bodies. A small number of Ptolemy's works are lost in time and are known only through their titles. Numerous studies of the natural and mathematical sciences give reason to contemporaries to consider Ptolemy one of the most prominent scientists, famous history. Worldwide fame, and most importantly, the works of Claudius have always been used as a treasure scientific knowledge ageless in time. Ptolemy's broad outlook and his non-typical, generalizing and systematizing mindset, and the author's high skill in presenting scientific postulates are unparalleled. From this point of view, the scientific works of Ptolemy and, of course, the Almagest became an ideal work for many scientists of different generations.

Ptolemy is the author of many other works on astronomy, astrology, geography, optics, music, etc., which were widely known during antiquity and the Middle Ages. An example can be given: “The Canopic Inscription”, “Tables at Hand”, “Planetary Hypotheses”, “Phases”, “Analemma”, “Planispherium”, “Quetruch”, “Geography”, “Optics”, “Harmonics”, etc.

"The Canopic Inscription"

The “Canopic Inscription” contains a list of all possible parameters of Ptolemy’s astronomical system, which was depicted on a stele dedicated to the Savior God. A study of the book “The Canopic Inscription” has proven that it was written much earlier than the world-famous “Almagest”.

"Phases of the Fixed Stars"

“Phases of the Fixed Stars” is not large-scale scientific work Claudius Ptolemy, is dedicated to weather predictions on the planet, which are based on one of the first methods of meteorology - observing the dates of synodic phenomena of stars in the Universe.

"Analemma"

Another treatise “Analemma”, where the most complex methods of work in astronomy are described to the reader in an accessible form.

"Planispherium"

“Planispherium” is a small creation of Ptolemy, which reveals the theory of stereographic projection in practice.

"The Four Books"

The “Quadribook” is the main manuscript on Ptolemy’s astrology, known to scientists under the second Latin name “Quadripartitum”.

During the life of Ptolemy, belief in astrology was very widespread among the inhabitants. Ptolemy was subject to his era. He perceived astrology as an obligatory addition to astronomy. Astrology, as always, predicts cataclysms and all kinds of events on our planet, taking into account the influence of the luminaries of the sky; astronomy provides information about the positions of stars, which is needed to make certain predictions. Ptolemy did not believe in fate; The scientist considered the influence of the celestial bodies to be only one of various factors determining events on our planet.

The significance of Ptolemy's works

Works of Ptolemy belongs leading place in the development of the science of astronomy. The significance of Claudius for her was immediately appreciated by her contemporaries. A huge amount of scientific literature is associated with the incredible work “Almagest”.

Based on the works of Ptolemy, contemporaries dreamed of improving or changing their works in the field of science about the celestial bodies. But all of the above led to the fact that Copernicus created his teaching, and it was based on the work of Claudius Ptolemy.

Over time, the importance of Ptolemy's works is not downplayed, but even increases. The talented Claudius Ptolemy based his scientific discoveries contributed the results of his predecessors.

IN historical literature Unfortunately, there is no information about the biography and place of birth of the famous scientist. We can only guess and fantasize about the life events of the astronomer - the hero.