The section is very easy to use. It is enough to enter the desired word in the proposed field, and we will give you a list of its meanings. I would like to note that our site provides data from various sources - encyclopedic, explanatory, word-formation dictionaries. Also here you can get acquainted with examples of the use of the word you entered.

Bukovina

bukovina in the crossword dictionary

Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1998

bukovina

the historical name (from the 15th century) of a part of the territory of the modern Chernivtsi region in Ukraine (Northern Bukovina) and the Suceava region in Romania (Southern Bukovina).

Bukovina

the historical name of the territory that is part of the modern Chernivtsi region of the Ukrainian SSR and the Suceava region of the SRR. It got its name from the beech forests that covered most of its territory. Northern Bukovina in the 1st millennium was inhabited by the East Slavic tribes of Tivertsy and White Croats. At the present time, mainly Ukrainians and Russians live in Northern B. In the 10th and 12th centuries. was part of Kievan Rus, in the 13th - 1st half of the 14th centuries. ≈ to the Galicia-Volyn principality. In the 14th century. went to the Moldavian principality, from the beginning of the 16th century. until 1774 was ruled by the Turks, and then until 1918 was part of Austria-Hungary. Part of northern Bulgaria, according to the Bucharest Peace Treaty of 1812, went to Russia. Northern Bolivia was closely connected with Ukraine. The peasants participated in liberation war Ukrainian people in 1648-54 on the side of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. In the 40s. 19th century In northern B., an uprising took place under the leadership of L. Kobylitsa. The revolution of 1848 forced the Austrian government to abolish serfdom. But living conditions remained extremely difficult; from 1901 to 1910 about 50 thousand people emigrated, mainly Ukrainians. Under the influence of the Revolution of 1905-07, the revolutionary movement expanded in northern Bulgaria, and the influence of the Bolsheviks grew. Great October socialist revolution engulfed Northern Byelorussia On November 3, 1918, the Bukovyna People's Veche decided to reunite Northern Byelorussia with Soviet Ukraine, and on the same day a provisional Central Committee of the Communist Party of Bukovina was elected, headed by S. Kanyuk. In November 1918, Romanian troops occupied Northern Bulgaria. In 1940, by agreement with Romania, Northern Bulgaria was returned to the USSR and reunited with the Ukrainian SSR, and the Chernivtsi Oblast was created on its territory. During the Great Patriotic War underground party and Komsomol organizations and partisan detachments operated in northern Bulgaria. Northern Bulgaria was liberated by the Soviet Army from the German fascist troops in March or April 1944.

South Bukovina in ancient times was inhabited by the Wallachians and Slavs. Currently, it is mainly inhabited by Romanians. In the 12th and 13th centuries. was part of the Galicia-Volyn principality, in the 14th century. became the center of the formation of the feudal Moldavian principality. From the beginning of the 16th century. under Turkish rule, from 1774 to 1918 as part of the Austrian Empire. In 1918 it became part of Romania, where it was one of the most economically backward lands. With the liberation of Southern Bulgaria by the Soviet Army in 1944 and the establishment of popular power on its territory, it turned into an industrial-agrarian region of the Socialist Republic of Romania.

Lit .: Kompaniec I. I., Stanovische i struggle of the working masses of Galchini, Bukovina and Transcarpathia on the cob XX century. (1900-1919 rock), K., 1960: Grigorenko O.S., Bukovina vchora i sogodni, K., 1967.

Bukovina (football club)

"Bukovyna" - Ukrainian football club from the city of Chernivtsi. Founded in 1958. IN soviet times the team twice (in 1982 and 1988) became the winner of the Ukrainian SSR championship and three times (in 1968, 1980 and 1989) the silver medalist of the Ukrainian SSR championship. Twice they reached the quarterfinals of the Ukrainian SSR Cup. During the days of independent Ukraine, the team became the silver medalist of the First League of Ukraine in 1996, and twice the winner of the Second League of Ukraine in 2000 and 2010.

Bukovina (disambiguation)

Bukovyna:

- Bukovina - region in Eastern Europe.

- Duchy of Bukovina - crown land in the Austro-Hungarian empire (1849-1918)

- Bukovina is a Ukrainian football club from the city of Chernivtsi.

- Bukovina is a stadium in the city of Chernivtsi.

- Bukovina is a village in Slovakia, in the Liptovsky Mikulas region of the Zilina region.

- Bukovina is a village in the Lviv region of Ukraine.

- Bukovina is a ghetto of the Second World War in the Lviv region of Ukraine.

- Bukowina Tatrzańska is a rural commune in Poland, part of the Tatrivske County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship.

Bukovina (stadium)

Sports and recreation institution "Bukovina" - stadium in Chernivtsi. Home arena of the Bukovina football team. Opened in 1967.

It is located in the city center, not far from the Taras Shevchenko Park of Culture and Leisure.

In 2000, plastic seats were installed in the stadium.

On the territory of SOU "Bukovina" there are also: a mini-football ground with artificial turf, where amateur competitions take place, in particular, the mini-football championship of Chernivtsi, the championship of various educational institutions of the region; as well as a beach volleyball court and tennis court. The construction of a handball court is underway.

In 2015, the stadium was reconstructed instead of an electronic 15 × 10 scoreboard, and a digital information board was installed.

Examples of the use of the word Bukovina in literature.

Bukovina is the last missing part of a united Ukraine and that for this reason the Soviet government attaches importance to resolving this issue simultaneously with the Bessarabian one.

Molotov objected, saying that Bukovina is the last missing part of a united Ukraine and that for this reason the Soviet government attaches importance to resolving this issue simultaneously with the Bessarabian one. Molotov promised to take into account our economic interests in Romania in the spirit that is most favorable to us.

Fourteenth - nineteenth century

Hasidism in Bukovina

Holocaust in Bukovina

In July 1941, Northern Bukovina was occupied by German and Romanian troops, who began exterminating Jews. Jews were mobilized for forced labor. On October 11, 1941, a ghetto was created in Chernivtsi; 40 thousand Jews from this ghetto, and then another 35 thousand from the surrounding places were sent to the camps of Transnistria.

Post-war Bukovina

At the end of World War II, Bukovina was again divided between Romania and the USSR. The Romanian authorities allowed Jews to repatriate to Israel from the southern part of Bukovina, which belonged to Romania, in which only a small number of Jews remained. In 1970, 37,459 Jews lived in the Chernivtsi region. In 1971, the limited repatriation of Jews from Soviet Bukovina to Israel began.

In the 1970s-80s. Bukovina is one of the centers of the revival of national Jewish identity and the struggle for the right to repatriation. From here tens of thousands of Jews left for Israel. In 1988, the first Jewish samizdat magazine in Ukraine was published in Chernivtsi (see Samizdat. Jewish Samizdat; editor I. Zisels (born 1946), later co-chairman of the All-Union Vaad, 1989–92, chairman of the Ukrainian Vaad since 1991. ). Jewish life is reviving, religious communities and cultural societies are being created.

For the Jews of Bukovina after the proclamation of Ukraine's independence, see Ukraine. Jews in independent Ukraine (since 1991).

Notification: The preliminary basis of this article was the articleIn 1940, the USSR, in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and with the help of military blackmail, annexed Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, which at that time were part of Romania, but during the Second World War it was occupied by the Germans and Romanians. In 1944, Soviet troops returned Northern Bukovina. In the same year, Southern Bukovina, which constituted 60% of the Bukovinian lands and was inhabited mainly by Romanians, was transferred to the Socialist Republic of Romania. Northern Bukovina became part of the USSR and became part of the Chernivtsi region of the Ukrainian SSR, now Ukraine.

Bukovina is a historical and geographical region in the Southern Carpathian region. In nude time, it covers parts of the territory of the modern Chernivtsi region in Ukraine (Northern Bukovina) and the Suceava region in Romania (South Bukovina).

ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BORDER

Some parts of the territory of Bukovitsa were different sides borders, but this does not prevent local residents from remaining faithful to traditions.

The majority of the population of Northern Bukovina are Ukrainians, followed by Romanians and Moldovans - descendants of the inhabitants of the once united Bukovina, their number is one-fifth of the total population of Northern Bukovina.

There is an extremely curious linguistic picture: although Ukrainian is the only state language, the majority of the population speaks two or more languages: Ukrainians and Moldovans speak Russian, Poles speak Ukrainian, and older Ukrainians have not forgotten Romanian either.

Northern Bukovina is covered with forests dominated by spruce, fir and, of course, beech. The rich survived animal world: Carpathian deer, roe deer, wild boar, fox.

The rivers of Bukovina have long been known as waterways for rafting forests from the Carpathian Mountains to the plains. The path was short, but extremely dangerous, the rafting profession in Bukovina was always considered extremely risky, legends and songs were composed about these desperate guys. Nowadays, a special type of water tourism has appeared on these rivers - sports mountain rafting on traditional long Bukovina rafts: a pleasure not for the faint of heart, since the current here is swift, there are many treacherous rapids, and the channel is extremely winding.

Many local sights are associated with the Ukrainian movement of the Carpathian oprishki, especially with the name of the rebel leader Oleksa Dov-bush (1700-1745). There are known “Dovbush stones”, “Dovbush rocks”, but the most popular and visited is “Dovbush cave” in Putivl region.

Bukovynians have many holidays, the most popular are the Ukrainian "Exit to the meadows", "Shovkova Kositsya" and the holiday of humor and folklore "Zakharetskiy garchik", as well as the Romanian national holidays "Mercisor", "Limba noastre chya romine" and "Florile Dalbe ", In which all national and cultural organizations of the region participate.

Chernivtsi - main city Northern Bukovina and the historical center of all Bukovina. The city's prosperity was facilitated by its location at the intersection of trade routes from northwestern Europe to the Balkans and Turkey. As a result of wars and power changes from Chernivtsi in 1940, almost all Germans were evicted; in Soviet times, the number of Poles and Romanians sharply decreased. Now the majority of the population in the city is Ukrainians. As for the Jews, who under the Romanians accounted for almost a third of the city's population, most of them died during the Second World War in numerous German concentration camps. After the war, most of the survivors fled to Romania.

Southern Bukovina in Romania includes one Suceava county. Romanians are the majority of the population in South Bukovina, followed by the Roma with a wide gap. The capital city of the county is called Suceava, and it contains the main value of South Bukovina - the Throne Fortress, the ancient place of the coronation of Moldovan rulers.

FUN FACTS

■ Television of Northern Bukovina (Ukraine) broadcasts news in Ukrainian, but speech in Russian is given without translation, and after the end of the release, the same program follows, but in Romanian and with a different presenter.

■ The name of the town Zastavna, according to local residents, does not come from the customs “outpost” that was once located here at the crossing of the Sovitsa River, but from the location of the city behind three ponds: “becoming” is in Ukrainian and means “pond”.

■ People's Bukovinian hero Oleksa Dovbush suffered from dumbness in childhood, but he was healed by Joseph Yavny. People like Yavny were called molfars in Bukovina: they were healers, healers, keepers of ancient knowledge and culture of Bukovyns. The name "molfar" comes from the word "molf" - the object on which the spell is cast.

■ In Russian Ryazan in the 1970s. Entuziastov Avenue was renamed into Chernivtska Street - in honor of the city of Chernivtsi, which is sister city of Ryazan.

■ The name of the center of South Bukovina, which is unusual for a Slav's ear, is Suceava, as it is commonly believed, from the Hungarian word suchshvar, literally translated as “castle-mechanic”. According to another version, the city inherited the name from the river, and the word itself is of Ukrainian origin.

■ The largest influx of Poles into Bukovina began during the Austrian rule, when Bukovina was united with Galicia under the name of Chernivtsi District. Many of those who arrived were gurals - a population living in the highlands of Poland. They became the main distributors of Catholicism in Bukovina.

ATTRACTIONS

■ Natural: Vyzhnytskyi National Natural Park, Gorny Eye Lake, Nemchich Pass, Kamennaya Bogachka Rock, or the Zaklyat Rock, Kaliman Mountains.

■ Religious: a wooden church (village Selyatyn, 17th century), the Greek Catholic Church of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos (Storozhinets, 1865), St. Nicholas Church (Putilsky district, 1886).

■ Historical: Throne Fortress (Suceava, Romania, XIV century), Oleksa Dovbush's cave, museum-estate of Ukrainian literary figure Yuri Fedkovich (Putila village, XVIII century), Memorial house-museum of the writer Mikhail Sadovianu (Falticheni, Romania).

■ Architectural: the Flonders Palace (Storozhinets, 1880), the Town Hall (Storozhinets, 1905).

■ G. Chernivtsi: wooden Nicholas Church (1607), a cathedral in the style of late classicism (1844-1864), Museum of History and Culture of Jews of Bukovina, Chernivtsi national University named after Yuri Fedkovich (the former residence of the Orthodox metropolitans of Bukovina and Dalmatia, 1882), a Jesuit church in the neo-Gothic style (1893-1894). Museum of Folk Architecture and Life, Museum of Bukovynian Diaspora, architectural ensemble of Market Square (XVIII-XIX centuries), Town Hall (1840s), Theater Square (early XX century), Chernivtsi Theater (1904-1905).

Atlas. The whole world is in your hands №245

Bukovyna is the smallest of the five historical regions of Western Ukraine, occupying the smallest in the country Chernivtsi region (8.1 thousand square kilometers - only 8 times larger than Moscow), and even then not all. Bukovina differs from Volyn in that it was never part of the Commonwealth - for many centuries this region was associated with Romania and its predecessors.

And this is a completely different Western Ukraine. Unlike Galicia with its luxury and religion, from Podolia with its endless war, Bukovina is a quiet, cozy and not preoccupied with national issues outskirts of all states that owned it.

The name Bukovina was given by beech - a broad-leaved tree, a close relative of oak. Beech forests are one of the "calling cards" of the Carpathians and the Balkans, and the beech itself can be easily identified by its stone-gray bark. However, I'm not sure that the beeches were photographed here - the color is the same, but the "correct" beeches have a smooth bark:

Basically, the landscapes of Bukovina look like this - the area is rugged and picturesque:

A little to the south of Chernivtsi rises the lonely mountain of Berda (517 meters) - either the highest point of the flat Ukraine, or the farthest of the Carpathian mountains:

And there are super-caves here. For example, the third largest in Western Ukraine (87 km) Cinderella, or Emil-Rakovytsya - almost the only one in the world international cave, which has entrances on both sides of the Ukrainian-Moldovan border.

Although the border is everywhere. Not state - so historical. An hour and a half from Chernivtsi to the north - and Podolia begins:

An hour and a half south - and Romania begins:

There is no pronounced natural border with Romania, and the Dniester separates Bukovina from Podolia:

In the center of Bukovina, the Prut River flows (no photos), on which Chernivtsi stands. The Prut forms the Romanian-Moldovan border.

In general, it would be more correct to call these lands Northern Bukovina - after all, Ukraine owns no more than a third of this historical region, which is part of Moldova. Moldova itself is a rather large historical region, in terms of diversity and originality it can be compared with the whole of Western Ukraine. And it is divided into three parts: Moldavia, Bessarabia (which is now independent) and Bukovina.

Historical coat of arms of Bukovina (small - Moldavian, large - Austrian).

However, the present Chernivtsi region came to Bukovina in about the same way as Krakow to Galicia. Before Mongol invasion it was territory Ancient Rus: in 1001, by order of Vladimir Krasnoe Solnyshko, Khotin was founded, and in the 12th century Yaroslav Osmomysl laid the foundation for Choren, the predecessor of Chernivtsi. After the Mongol invasion, "proto-Bukovina", apparently, entered the Podolsk ulus, in the 1340s it was conquered by Hungary, and in 1359, after the uprising of Bohdan the First, it became part of the Moldavian principality independent from Hungary. Its capital was located in Bukovina - first Siret, and from 1385 - Suceava, which became the capital of Moldova in 1385-1579.

Throne fortress of the Moldavian rulers (from Wikipedia)

Here was also Putna - "Jerusalem of the Romanian people", a monastery founded in 1469 by Stephen the Great and became his tomb. For Romania, this is roughly the same as for Russia the Trinity-Sergius Lavra.

From the site "Pravoslavie.Ru".

From Wikipedia.

But despite its proximity to one of the centers of Romanian statehood, Northern Bukovina remained a Slavic region throughout its history. However, it was a periphery - almost all the main events in the life of Bukovina and Moldavia unfolded to the south, whether it was civil strife or a long and hopeless war with the Turks. In 1403, in a message to Lviv merchants, Chernivtsi was first mentioned as one of the centers of Polish-Moldovan trade. The most ancient architectural monument of Bukovina can be considered the Assumption Church in the village of Luzhany (where I never got there), founded no later than the 15th century (and probably back in the Old Russian period).

However, Khotin received special significance at this time:

In 1457-1504, Moldavia was ruled by Stephen the Great, or Stefan cel Mare, who in many ways resembled his contemporary Ivan the Third - a wise, strong and humane (by the standards of the Middle Ages, of course!) Ruler who replaced the boyars and successfully fought against the enemies. Under him, Moldova not only was absolutely independent, but also became one of the strongest and richest powers in Eastern Europe.

The brightest layer of those times in Bessarabia is the "stone belt" along the Dniester, the fortresses of Khotin, Soroka, Tigina (Bender) and Chetatya-Albe (Akkerman, Belgorod-Dnestrovsky). As a result, only one remained in Moldova (without Transnistria) - Sorokskaya. The Khotyn fortress, heavily rebuilt in the following centuries, is one of the most beautiful and powerful in Ukraine:

However, the Khotyn region is isolated from Bukovina - it is really more correct to attribute it to Bessarabia, and the Russian garrison church of the 19th century is a confirmation of this. However, more on that later.

Another monument of medieval Moldavia is the Old Ilyinsky Church (1560) in the village of Toporovtsi:

Stefan cel Mare went down in history not only as a hero of Moldova, but also as a hero of Orthodoxy - it was during the years of his reign that Constantinople fell, and defending the faith, he was close to the fact that Moldova would turn into the Third Rome ... but after his death no worthy successor was found. First, Mr. Bogdan Krivoy began to improve relations with Turkey and got involved in a war with Poland, which he lost; Stefan the Fourth (or Stefanice - "Stefanchik") was mired in palace intrigues, started a war with Wallachia and was poisoned. The ruler Peter Rares tried to centralize the power, but the Turks overthrew him, placing on the throne "their man" Stephen Lacusta, thus making Moldova a vassal. The Lords were replaced almost every year, sometimes Poland and the Cossacks became friends, sometimes enemies. By the end of the 16th century, Moldova finally became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Ruins of a mosque in Khotin.

Two hundred years of Ottoman rule (until 1775) were probably the most difficult period in the history of Bukovina. The legacy of this era is the churches-huts, of which there are still many in the Chernivtsi region:

This phenomenon is of the same type as synagogues, Tatar mosques, Old Believer churches: aesthetics were sacrificed for secrecy and simplicity. Such temples were built where it was understood that it was impossible to save them, and the main criterion was their restoration. The same applies to icon painting - there is even such a thing as "Bukovinian primitivism". And at the same time, unlike the Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire did not impose its religion on the conquered peoples - and even in this state, Bukovina remained Orthodox:

But in general, until the turn of the 18-19th centuries, Bukovina lived underground. However, in 1775, taking advantage of the defeat of the Turks in the Russo-Turkish War, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa annexed the region:

(City Hall in Chernivtsi)

And in 1812, along with all Bessarabia, Khotin became part of Russia:

But if Khotin was the far outskirts of the province with the center in Chisinau, then Chernivtsi (which became a city since 1491) turned out to be the center of the Bukovina district, first subordinate to the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, and in 1849 set aside as a separate province. And it was during this era that Bukovina flourished - it seems that in the 1850s-1930s at least 90% of its heritage was created.

Chernivtsi turned into a small (67 thousand inhabitants at the beginning of the 20th century), but a luxurious city worthy of Lviv:

With the same riot of secession:

And the sculptural nudity so beloved by the Austrians (and the specific forms of some sculptures would have puzzled Freud):

Under the Austrians, railways came here (1866), and a luxurious station appeared:

Moreover, it is along the Austrian road, through Lviv, that trains go to Chernivtsi now. After all, a more direct road to the east crosses the border of Moldova several times. I have already traveled by train Moscow-Chernivtsi three times - there and back to Galicia and only "there" to Podolia, and this train is absolutely the most terrible of all that I have used. And a feature of Bukovina and Ivano-Frankivsk region can be called old diesel trains D1, produced by Hungary by order of the USSR (1960-80s):

And another road leads to Romania, and closer to the border, I even saw sections of the combined (three rails) "Russian" and "Stephen" track (I did not get into the frame).

Churches were also built at this time, mostly Orthodox. The architecture and details are very characteristic - much the same, only simpler, most rural churches look like:

Orthodoxy under Austria-Hungary remained the dominant religion of Bukovina. It was the seat of the Bukovina-Dalmatian Metropolitanate, which was part of the "home" Karlovtsy Patriarchate, which existed in the years 1848-1920 in the city of Sremski Karlovci, the center of the Austrian province of Serbian Vojvodina.

Cathedral in Chernivtsi (1844-64)

Bukovina played a very special role in the history of Russian Orthodoxy. But not the Moscow Patriarchate, but the Old Believers. Under Nicholas I, the period of relative religious freedom begun in Russia by Catherine II ended. In 1827 the Old Believers were forbidden to accept priests from among the New Believers, and since the Old Believers had no bishops, this threatened them with the loss of religion. In 1838, Old Believers monks Pavel and Alimpiy arrived in Bukovina, and in 1846 they found the Greek Ambrose Pope-Georgopolou, the former Metropolitan of Bukovina-Dalmatsk, deposed in 1840 by the Patriarch of Constantinople and living in poverty in the Ottoman capital.

Pavel and Alimpiy came to him not empty-handed, but with the permission received back in 1844 from the Austrian authorities to create an Old Believer metropolis. The center has already been found - the ancient village of Belaya Krinitsa, founded by the Lipovans - fugitive Old Believers from among the Cossacks (many of their settlements are scattered throughout Moldova from Bukovina to the Danube Delta).

In 1846 Ambrose became a metropolitan for the second time - but now of a new confession: the Russian Orthodox Old Believers Church, better known as the Belokrinitsky Consent. In our time, out of 2 million Old Believers, 1.5 million belong to the RPSTs. And although in 1853 the center of the RPSTs was moved back to Moscow, Belaya Krinitsa remained one of the main shrines of the Old Belief:

Even the Austrian period is notable for numerous architectural experiments in the field of historicism. The architecture of Bukovina differed from the architecture of Galicia by the active use of the techniques of Moldavian architecture - for example, tiled ornaments on the roofs (in this case, the Chernivtsi University, the ex-residence of the Bukovina-Dalmatian metropolitans):

Or the New Ilyinsky Church in Toporovtsi - a typical Romanian temple, clearly inspired by the monasteries of Moldova, although it was built in 1914:

The first World War here it was much easier than in Galicia and Podolia - although the city was occupied three times by Russian troops and was the center of the Chernivtsi province of the Galician governor-general, the disintegration of Austria-Hungary was not followed by new wars. Bukovina simply became one of the counties (counties) of Romania.

The development of architecture did not seem to be interrupted, just to replace “Moldavian motives came Wallachian - the so-called“ non-Rynkovian style. ”For example, St. Nicholas Church (1927-39) in Chernivtsi, nicknamed the“ Drunken Church ”for its form, is just a stylization of the Episcopal Church in the capital of medieval Wallachia Curtea de Arges:

And civilian "non-market" houses basically look like this (left):

But the most characteristic layer of the Romanian period is functionalism, which here is emphatically unaesthetic, which makes it interesting:

This, for example, is not a Khrushchev, but the Romanian People's House (1937) in Chernivtsi:

Then there was the Second World War - and again, not as bloody as in Galicia. Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia were handed over to the USSR by Romania in 1940 on a voluntary-compulsory basis, therefore the scale of repression was not the same here. In 1941-44, Bukovina was again a part of Romania, and there was a ghetto in Chernivtsi - however, Romanians are still not Germans, and the Holocaust was not so total here. Thanks to the efforts of the mayor of Chernivtsi, Traian Popovich, more than 20 thousand Jews were saved - he simply managed to convince Antonescu that the economy of the city is based on Jews.

The Soviet period in the life of Bukovina was also very quiet. Bukovina again became a cozy hinterland on the outskirts of the empire. Chernivtsi turned into a large industrial center of precision production.

And in independent Ukraine Bukovina differs from its neighbors. The first thing that catches your eye here compared to Podolia is religiosity. The same as in Galicia, chapels along the roads - only not Greek Catholic, but Orthodox:

And in comparison with Galicia, it is striking that there is clearly more sympathy for Russia and the USSR. There are streets of Chkalov, Volodarsky, Moscow Olympics, etc. Here you can see the traditional symbols of Victory (St. George's ribbons, sickle-and-hammers, silhouettes of the Spasskaya Tower), monuments, tanks, and perhaps there are no Lenins here:

In general, Bukovina gives the impression of a very tolerant region. Moreover, this is not a "melting pot" - rather, a place where different peoples got along peacefully. What is the reason - I do not know. Perhaps with an almost complete absence of periods of militant catholicization, or perhaps with the fact that there has never been an ethnic oppression of Ukrainians for whom Poland was "famous".

And a little about rural Bukovina.

The traditional village has survived here only in skansen:

But many other vestiges remain. For example, wood carving:

Both Romanian and Soviet. Wooden stops are not only in the Russian North:

And along the roads here and there are old windmills. On the Chernovtsy-Khotin highway, I saw at least three of them. They don't work, they just decorate the landscape - and this is very handy, given the primitiveness of wooden churches. However, I took this shot in a scansen, but the windmills near the track are the same:

And modern rural Bukovina is even more impressive than rural Galicia. If in Galicia an ordinary peasant house is drawn to the "dacha of a wealthy Muscovite", then in Bukovina - to the "dacha of an average businessman":

I did not take pictures over the fence, so take my word for it - in the courtyards of similar houses ( but not this particular !!!

) chickens walk on the tile, there is a "Zaporozhets" near the house, and even water is taken from a well. This phenomenon can hardly be understood in Russia, where they are proud of their poverty (especially imaginary).

However, here I finally filmed what I saw many times in Galicia - dates on huts. Almost all dated - 1960-80s:

By the way, quite a lot of Romanians and Moldovans live here to this day - about 20% throughout the region (12% Romanians, 7% Moldovans), and in the Hertsaevsky district, close to Chernivtsi, all 90% (it was part of South Bukovina) ... On the way from Chertkovo I noticed that there are many obvious non-Slavs here - in Moscow I would have taken them for Caucasians. But in general, after a couple of hours, the differences in appearance you cease to notice, and at least I did not feel the presence of other people in any way.

And in general, despite the terrible weather, I really liked Bukovina.

The next 4 parts are about Chernivtsi.

PODOLIYA and BUKOVINA-2010

Bukovina is one of the most peculiar ethnic regions of historical Russia. This region is very small in size - 8.1 thousand square meters. km. All this territory is occupied by the Chernivtsi region of Ukraine. However, there is also South Bukovina, which is part of Romania. Despite its small size (in the Soviet Union, the Chernivtsi region was the smallest in terms of territory among all regions of the country, and one of the smallest in terms of population), the ethnic history of Bukovina is unique.

The natural conditions of Bukovina are very favorable. The southern and central parts of the region are occupied by the Carpathians and their foothills, the northern part is an elevated plain between the Prut and Dniester rivers. The highest mountains in the south: the Maksimets, Tomnatik, Cherny Dil, Yarovitsa ranges from the very high point mountain Yarovitsa (1565 m). Forests are widespread in the mountains and foothills. The climate is moderately continental, humid, with warm summers and mild winters, with pronounced high-altitude zoning. Chernivtsi region is rich in water resources, 75 rivers with a length of more than 10 kilometers flow through its small territory; all rivers belong to the Black Sea basin, the largest of which are the Dniester, Prut, Cheremosh (with tributaries White Cheremosh and Putila) and Siret (with Small Siret). Mineral resources are represented mainly by mineral construction raw materials; many sources of mineral waters.

In 2001, 922.8 thousand inhabitants of more than 60 nationalities lived on the territory of the Chernivtsi region. The most numerous among them, according to the official Ukrainian census, are Ukrainians. However, we recall that the Carpathian Rusyns are officially considered Ukrainians in Ukraine.

According to the 2001 Ukrainian census, the population of the region includes: Ukrainians - 75.0% (693,000); Romanians - 12.5% \u200b\u200b(115,000); Moldovans - 7.3% (67,000); Russians - 4.1% (38,000); Poles - 0.4% (4,000); Belarusians - 0.2%; Jews - 0.2%; others - 0.4%.

As in all Ukrainian censuses, these figures, to put it mildly, need clarification. In particular, there are actually few “Ukrainians” here, Ruthenians prevail, who are considered by official statistics as Ukrainians. Moreover, the Bukovinian Rusyns differ from the Rusyns of Galicia and Transcarpathia.

Areas with a predominance of the Ruthenian (“Ukrainian”) population occupy the western, northern and northeastern parts of the region. It should be noted that among the Ukrainian population of the Chernivtsi region, there are three rather large self-identifying sub-ethnic groups: Bukovina Hutsuls, who live mainly in the western high-mountain regions, Rusnaks or "Bessarabtsy" inhabiting the northeastern regions of the region, and the Rusyns themselves, or Podolyans, who live in the north. -the western part of the region on the plain between the Dniester and Prut rivers. All these sub-ethnic groups differ from each other in their way of life and dialectal characteristics. In addition, not all Bukovinian Rusyns have a Ukrainian identity. Finally, earlier, a significant role in the economic life of Bukovina was played by Russian Old Believers, who are here called Lipovans.

The second most populous national group is the Romanians. The third largest ethnic group is Moldovans. The difference between Romanians and Moldovans in the Chernivtsi region is rather arbitrary - Moldovans are those Eastern Romanesque residents who live in the territory that was part of the Moldavian principality until 1774, before joining Austria, Romanians are those Eastern Romans who moved here from the Romanian territory Transylvania and other Romanian lands. In fact, the Moldovans and Romanians of the Chernivtsi region are one separate ethnic group, distinct from the Moldovans from Moldavia and Romanians from Romania. At the same time, 10% of Chernivtsi Romanians in 1989 named Ukrainian as their native language (that is, the local East Slavic).

The Chernivtsi region stands out against the general Ukrainian background by a relatively low share of the Russian population - less than 5% of residents identify themselves as Russians. But at the same time, in terms of the number of Russian-speaking residents, Bukovina ranks first among the regions of western Ukraine. In many parliamentary and presidential elections in Ukraine, the Chernivtsi region does not vote at all as expected from western Ukraine. The reasons for this paradox lie in the peculiarities of the history of the region.

It is no less significant that of all religious associations in the region, the most numerous are the communities of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. Among other religious trends traditional for the Chernivtsi region, one should indicate (in descending order of the number of followers) the Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Greek Catholic, Russian Orthodox Old Believers and Evangelical Lutheran churches, as well as communities of Jewish cult. In addition, a number of non-traditional Protestant denominations are very numerous in the region, among which the Evangelical Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists and Christians of the Evangelical faith stand out first of all.

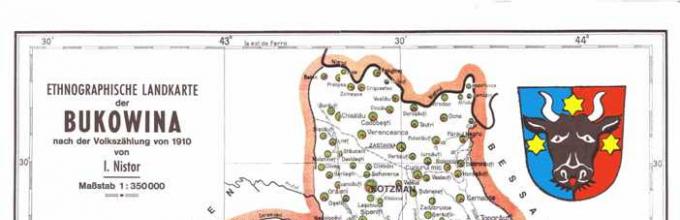

Note. As you can see on this Austrian ethnographic mapcompiled in 1910, no Ukrainians have yet been found in Bukovina. But there were Rusyns. At the same time, Lipovans appear. Meanwhile, Lipovans are Russian Old Believers.

The Slavs inhabited this land in ancient times. Probably Bukovina was one of the cradles of the Eastern Slavs. Antes, White Croats and Tivertsy lived here. Many elements of the everyday culture of the ancient Slavs remained characteristic of the culture of Bukovyns. On the territory of Northern Bukovina, Slavic settlements of the VI-VII centuries. found in 40 points, and the VIII-IX centuries. - in more than 150 points.

Since the X century Bukovina was part of Kievan Rus. After the disintegration of Rus into the specific principalities of Bukovina, the Galician princes ruled. Probably under Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153-1187) a fortress was built on the Prut River, which later became the city of Chernivtsi. The fortress with a trade and craft settlement was called Chern, or Black City, apparently because of the black wooden walls. There is also a mention of Cherny in the famous chronicle "List of Russian cities, far and near." The ruins of the fortress have survived to our time near the modern village of Lenkovtsy (now within the city limits of Chernivtsi).

Only from the XIV century the history of Bukovina began to differ from the history of other Western Russian lands. The foothills of the Carpathians, devastated by the Tatar invasions, began to be settled by the Roman-speaking shepherds of the Wallachians. Gradually, there are more and more of them, and the flat areas between the Dniester and Prut rivers become Wallachian. The mountainous regions of modern Bukovina remain Slavic, but fall under the rule of the Wallachians. In 1340, after the fall of the Galician principality, captured by Poland, the local Rusyns preferred to go under the rule of the Orthodox Vlachs. As a result, Bukovina becomes the center of the Moldavian principality. Here are the ancient capital of Moldavia Suchava, the Putna monastery with the tombs of princes and the most revered ancient monasteries of Moldova.

Under the name Bukovina, this region is mentioned in the agreement of 1482 between the Polish king Vladislav Jagiello and the Hungarian king Sigmund. The origin of the name is clear - the beech actually grows throughout the region.

Since the 15th century, Bukovina, together with all of Moldova, falls under the rule ottoman Empire... Bukovina differed from the rest of the Moldovan territories only in that the Slavic Rusyn population absolutely prevailed here. Constant wars between the Habsburgs and the Turks ravaged these lands. By the end of Turkish rule in the third quarter of the 18th century, only 75 thousand inhabitants remained in the whole of Bukovina. In the city of Chernivtsi, the capital of the region, there were about 200 wooden houses, three churches and about 1,200 residents.

During the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-74. Bukovina was occupied by the Russian army. However, despite Russia's brilliant victory in this war, Bukovina went to Austria! This was the price to pay for Austrian neutrality in the war. So Austria, as a result of someone else's victory, annexed a piece of Russian territory.

So, in 1774 Bukovina fell under the rule of the Austrian Empire, and for 144 years it remains part of the Habsburg monarchy. And again, its history begins to differ from the history of the rest of the Russian lands.

Unlike Galicia, the Bukovinian aristocracy was of Moldovan origin, church union was not widespread here. Local residents called themselves Rusyns and referred themselves to the Russian Orthodox world. That, however, did not prevent them from simultaneously being loyal subjects of the Austrian monarchy.

At the same time, there was no serfdom in Bukovina, although various forms personal dependencies existed until 1918.

Bukovina was a multinational land. In addition to the Rusyns and Vlachs, from the era of the Moldavian principality, Jews who were engaged in trade lived here. Since the time of Austrian rule, Germans began to appear in the region. Already in 1782, the first German settlements appeared here. In the future, the German colonization of Bukovina continued. German as the official language of the Austrian Empire, which was spoken by the German colonists, which was more or less mastered by the Yiddish-speaking Jews and which was taught in schools, and, finally, which was filled official documents, gradually turned into the language of interethnic communication of all Bukovyns. Rusyns from Galicia also settled in the region. At the end of the 18th century, Russian Old Believers-Lipovans also arrived in Bukovina.

In general, the urban population of the region was Germanized, the aristocracy also gradually merged into the nobility of the Austrian Empire, receiving the prefix "von" to their surname. Only "priest and slave" remained Russian in the region.

Rusyns zealously professed Orthodoxy, differed in linguistic and cultural differences from the Malorussians of Galicia and Russian Little Russia. Historically, specific features of the Ruthenian ethnic character have also developed. A number of researchers of the life and life of the Bukovinian Rusyns (such as P. Nestorovsky, G. Kupchanko, V. Kelsiev) gave such characteristics to the Bukovinian Rusyns late XIX centuries: Bukovinian Rusyns are much more mobile, enterprising and energetic than Transnistrian ones. This is noticeable in the occupations of the Bukovinian people. Apart from arable farming, they flourished gardening, horticulture, handicraft production, etc. Offshore fishing, especially for seasonal work in Russia, was also developed. All this, undoubtedly, speaks of the energy of the Bukovyns. It does not at all contradict the entrepreneurial spirit of the Bukovinian people, their character described by scientists as friendly and gentle. Ethnographers emphasized the politeness and modesty inherent in Rusyns. The family cultivated reverence and respect for elders, especially for parents. The younger always addressed the older ones with "you." Bukovyns are a neat, dapper and dandy people. Their taste for the elegant is more developed than that of other Rusyns.

Ruthenian houses almost always face south. Every house had "Prysbu"(filling) and was painted, except for the back side, with white lime. The houses were kept neat, as they were often smeared outside and inside.

The linguistic specificity of the Rusyns was due to the fact that the Rusyns mostly avoided the process of linguistic “Ukrainization”. This allowed the Rusyns to preserve more ancient Russian linguistic forms than the Ukrainians managed to do. The Rusyn language, of all the southern Russian dialects, is closer to the Great Russian. According to the Soviet historian V. Mavrodin, the devastation and displacement of the population in the south of Kievan Rus led to the disappearance of the ancient local dialect forms of the language, however, they persisted for a long time in the north of Rus, as well as in the Carpathian and Transcarpathian regions.

So, in the Carpathian Mountains, including Bukovina, many features of the culture and language of Kievan Rus have been preserved, just like in the Russian North.

The end of constant wars contributed to the prosperity of the region. In 1849 Bukovina received a certain autonomy, becoming the crown province of the empire. Since 1867, Bukovina received the autonomous status of a "duchy" within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The duchy had a local parliament (Diet) of 31 deputies. Bukovina was represented by 9 deputies in the all-imperial parliament of Austria-Hungary. However, there were practically no Rusyns among the deputies of the Diet, except for the local Orthodox Metropolitan. So the majority of Bukovyns never knew what democracy was. The territory of the duchy was 10 441 km2.

Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the Austrian era for Bukovina was a time of economic growth and cultural development. Significant population growth was an indicator of this. If in 1790 only 80 thousand inhabitants lived in Bukovina, in 1835 - already 230 thousand, in 1851 - 380 thousand. In the second half of the 19th century, population growth continued rapidly. By 1914, about 800 thousand people lived in Bukovina. As you can see, in less than a century and a half, the population has increased more than 10 times.

According to the Russian encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron at the beginning of the 20th century, in 1887, 627 786 people lived in Bukovina (including the current Romanian South Bukovina), making up the population of 4 cities, 6 townships and 325 villages. By origin, according to the Austrian census, in Bukovina there were: 42% Rusyns, 12% Jews, 8% Germans, 3.25% Romanians, 3% Poles, 1.7% Hungarians, 0.5% Armenians and 0.3% Chekhov. In fact, there were significantly more Ruthenians, as evidenced by the data of the registration of religion. It should be borne in mind that the Orthodox called their faith "Voloshskaya". According to these data, 71% of all inhabitants were Orthodox in Bukovina. Another 3.3% were Greco-Roman Uniates. Uniates of Bukovina considered themselves Russians. The Uniate Church in Chernivtsi was called “Russian” and was located on Russishe Gasse Street. Among the representatives of other faiths were: 11% - Roman Catholics, 2.3% - Evangelicals (Protestants) and 12% - Jews.

The growth of the population of the city of Chernivtsi became an indicator of the region's prosperity. So, in 1816 the entire population of Chernivtsi was 5,416 people, in 1880 - already 45,600, in 1890 - 54,171. In 1866, railway Chernivtsi - Lviv, a power plant was built in 1895, an electric tram was put into operation in 1897, a water supply and sewerage system by 1912. The city was predominantly German-speaking (German was spoken by the Germans and most of the Jews, as well as many local residents of various origins).

In 1890, according to the Austrian census, in Chernivtsi there was such an ethnic composition of the population by language: 55,162 people spoke German (60.7%); in Romanian - 19,918 (21.9%); in Ukrainian (local Rusyn) - 12,984 (14.3%); Poles, Magyars and others, who indicated other languages \u200b\u200bas native, counted - 2 781 (3.1%). The city of Chernivtsi has become one of the centers of German, Jewish and Romanian culture. As for the Rusyns, due to their poverty, illiteracy, as well as the split between Muscophiles and Ukrainophiles, their cultural achievements are not great. However, the work of Olga Kobylyanskaya and Yuri Fedkovich is also included in the collection of cultural achievements of Bukovina.

The process of assimilation of Rusyns by the Romanians and, to a lesser extent, by the Germans, as well as the gradual Ukrainization - this also took place in the life of the Rusyns during the Austrian period of their history. Romanization has taken on a large scale. According to the calculations of the Ukrainian scientist G. Piddubny, in 1900-1910 32 villages from Ruthenian became Romanian. How the process of “romanization” of Rusyns looked like can be traced back to the genealogies of many famous Romanians. This is, for example, the genealogy of the great Romanian poet (native of southern Bukovina), Mikhail Eminescu (1850-1889). His father Georgy Eminovich was a native of the village of Kalineshty (Kalinovka) near Suceava and outwardly was a typical Rusyn: “he had blue eyes, spoke Rusyn and Russian well.” The poet's mother, named Raresh, was the daughter of Vasily Yurashka (Yurashko), a native of the Khotyn district (Russian Bessarabia), and Paraskiva Donetsu. Paraschiva's father was the Russian Don Cossack Alexei Potlov. And only one of the poet's great-grandmothers, perhaps, was a Moldovan.

Also, the leader of the Romanian ultranationalist organization "The Legion of Archangel Michael" of the 1920s and 1930s was of Rusyn origin. Corneliu Zeljko-Codreanu (his ancestors bore the name Zelenskiy).

On the other hand, among the leaders of the Ukrainian movement was a local aristocrat, the Romanian nobleman Nikolaus von Vasilko (!), Who did not speak either Russian, let alone Ukrainian language. As elsewhere in Ukraine, the founders of Ukrainians were not Ukrainians at all.

Of course, the Austrian power did not at all mean any involvement of the Bukovinians in a certain European civilization. The number of illiterates was approximately 90% of all inhabitants of the region. In fairness, it should be noted that illiteracy was often due to the fact that education in Bukovina went on german... At the same time, the Austrian authorities were very afraid of Russian influence, and in every possible way prevented the emergence of schools with the Russian language of instruction. Romanian schools have become somewhat widespread in the region. In Jewish educational institutions education was also in German. In 1875, the Chernivtsi University was established with three faculties: Orthodox theology, philosophy and law.

The Russian ("Muscovite") movement developed in Bukovina in difficult conditions. Russian public life in Chernivtsi begins with the founding in 1869 of the Ruska Besida society, the Ruska Rada political society (1870), and the Union student society (1875).

In opposition to the movement of Muscovites, the Austrian authorities began to encourage Ukrainians by opening schools with "mova" as one of the languages \u200b\u200bof instruction and a newspaper in Kulishovka. The fact that the text of the Ukrainian editions was incomprehensible to the Rusyns did not bother the Austrians. So Bukovina gradually began to Ukrainianize, although this process was not of such a large-scale nature as in Galicia. Since about 1884, the Bukovinian Rusyn movement took on a Ukrainian character. The Austrian authorities, dissatisfied with the slowness of the Ukrainians, took purely punitive actions against the Russian movement. So, in May 1910, the Bukovinian governor closed all Russian societies and organizations, including the society of Russian women, which contained a school of cutting and sewing, which probably posed a threat to the unity of Austria-Hungary. At the same time, the government confiscated all the property of the organizations, including the library of the society of Russian (that is, Russian-speaking with Russian identity) students.

It was much more difficult for the Austrian authorities to develop Ukrainianity in Bukovina than in Galicia, where the Uniate Church was the main stronghold of the Ukrainians. Orthodoxy prevailed in Bukovina, and the authorities had to resort to police measures.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, graduates of the Orthodox Theological Seminary in Bukovina gave such a written commitment: “I declare that I renounce the Russian nation, that from now on I will not call myself Russian, only Ukrainian, and only Ukrainian”. Seminarians who refused to sign this document did not receive a parish. The text of this oath of allegiance to Ukrainians was pronounced in German.

Professor S. Smal-Stotsky, another of the Ukrainian leaders of Bukovina, the only one of them of Ruthenian origin, also gave such a written commitment in German: “If I am appointed professor of the Ruthenian language at Chernivtsi University, I undertake to defend the scientific point of view that Ruthenian language independent language, not the dialect of the Russian language. " By the way, later Smal-Stotsky ended up under Austrian criminal court for embezzling several million crowns from the bank, of which he was chairman.

Nevertheless, by the beginning of the 20th century, the Ukrainians in Bukovina could not boast of any achievements, and by 1914 there were only a few dozen “conscious” Ukrainians. As a result of the split of the Ruthenian movement into Muscovites and Ukrainophiles, the Ruthenians, being the ethnic majority in the region, did not have a strong position either in politics, or in the economy, or in culture. The Rusyn movement as a whole was significantly inferior in organization to the Romanian one. Moreover, there were no Rusyn organizations in the southern part of Bukovina.

There was also the Bukovinian autonomous movement, which aimed to expand the autonomy of Bukovina within the framework of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most of the autonomists were local Germans and Jews, who were equally afraid of both the Russian and Ukrainian movements. However, the autonomists had some support from the Orthodox Rusyns, who were dissatisfied with the leadership of the Galician Uniates in Ukrainians. In general, Bukovynians of any ethnic origin were distinguished by strong local patriotism.

In general, let's note in fairness, interethnic contradictions in Bukovina did not have the character of confrontation, there were practically no ethnic conflicts in the region.

Despite the economic recovery, the region still remained quite backward. Landlessness, aggravation of national and social problems led to a fairly significant emigration of Bukovyns, including Rusyns. For 1880-1914 about 225 thousand Rusyns left for the countries of the New World. No less significant was the departure of Bukovinian Rusyns to Russian empire... Especially many Rusyns settled in the Bessarabian province, because, in addition to the neighborhood of these regions, the everyday culture of the Moldovans and Bessarabian Rusnaks was very similar to the Bukovinian ones. The 1897 census took into account 16 thousand Austrian citizens in one Bessarabian province of Russia, excluding those who had taken Russian citizenship.

Despite the economic recovery, the region still remained quite backward. Landlessness, aggravation of national and social problems led to a fairly significant emigration of Bukovyns, including Rusyns. For 1880-1914 about 225 thousand Rusyns left for the countries of the New World. No less significant was the departure of Bukovinian Rusyns to Russian empire... Especially many Rusyns settled in the Bessarabian province, because, in addition to the neighborhood of these regions, the everyday culture of the Moldovans and Bessarabian Rusnaks was very similar to the Bukovinian ones. The 1897 census took into account 16 thousand Austrian citizens in one Bessarabian province of Russia, excluding those who had taken Russian citizenship.

During the First World War Bukovina became a theater of military operations. Russian troops occupied Chernivtsi three times, and rolled back three times.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary on November 3, 1918, the Bukovyna folk veche took place in Chernivtsi. It proclaimed "unification not only with the Bolshevik Ukraine, but also with the Bolshevik Moscow." In November 1918, Romanian troops were brought into Bukovina. Until 1940, Romania was in control of Bukovina.

Under the Romanian government, the position of Bukovina was incomparably better than, for example, in Bessarabia. The latter was explained by the fact that here, due to the absence of a significant Russian (in the meaning of Great Russian) population, the policy of suppressing non-Romanian peoples was softer. However, fearing the strengthening of the Russian movement, the Romanian authorities continued the Austro-Hungarian policy of Ukrainizing the Rusyns of Bukovina. Under the control of the authorities, various Ukrainian organizations arose, newspapers and magazines with names such as "Samostiynist" and "Samostiyna Dumka" were published. But even timid attempts to create Russian organizations were suppressed immediately.

Of course, this did not mean the absence of social and national problems. In January 1919, a large peasant uprising broke out in the Khotyn region, which engulfed northern Bessarabia and western Bukovina. After the suppression of the uprising, at least 50 thousand Rusyns fled to the Soviet bank of the Dniester. In November 1919 in Chernivtsi the 113th Bukovina regiment, consisting mainly of Rusyns, rebelled. Having thrown 4 regiments against the rebels, the Romanian command suppressed the uprising.

In general, 853 thousand inhabitants lived in the Romanian Bukovina in 1930. The composition of the population, according to Romanian official data, was as follows: Ukrainians (Rusyns) - 38%, Romanians - 34%, Jews - 13%, Germans - 8%, Poles - 4%. Also, Hungarians, Russians (Lipovan Old Believers), Slovaks, Armenians, and Gypsies lived in small numbers. It should be noted that the Romanian authorities, trying to declare Ruthenians as Ukrainians, indicated such a “nationality” in the census form as “Ruthenians or Ukrainians”. It is clear that many Rusyns simply could not know the meaning of these terms, and called themselves Romanians, declaring loyalty to the Romanian statehood. In addition, 12,437 people identified themselves as Hutsuls.

In 1930, there were 112 thousand people in Chernivtsi. Of these, 29% of the inhabitants were Jews, 26% - Romanians, 23% - Germans, Ukrainians (Rusyns) - only 11%. The city continued to be largely German-speaking. The Romanian language and the speech of local Rusyns nevertheless became more widespread than in Austrian times.

Bukovina, under the Romanian rule, was generally a poor land. Of the 173 thousand peasant farms in the 30s, 72.5 thousand were landless, and 30 thousand had allotments of no more than half a hectare.

The Romanian authorities proclaimed that the Bukovinian Rusyns are Romanians who have forgotten their native language (although it would be more fair to say that these are Romanians - Slavs who have forgotten their language). Based on this official point of view, since 1926 the teaching of the local version of the Ukrainian language in schools has been discontinued. Only Romanian remained the only language of instruction in schools.

In 1940, the northern part of Bukovina became part of the Soviet Union and became the Chernivtsi region of Ukraine. Southern Bukovina remained part of Romania.

In the course of the socialist transformations that began in the Soviet part of Bukovina, large-scale nationalization was carried out, and the elimination of illiteracy began. As in Galicia, paradoxically, the reunification of the East Slavic lands led to the victory of Ukrainization, since the Rusyns were again declared Ukrainians, the few Russian organizations were closed as “Black Hundreds”, and their activists were subjected to repression. In 1940, another event took place in the ethnic history of Bukovina - almost the entire German population left for Germany.

In June-July 1941, the Chernivtsi region was occupied by the Romanian troops, who fought on the side of Germany against the SSR in 1941-44. The occupation regime of the Romanians was not much softer than the German one. The Romanian authorities, despite the official propaganda announcing the "return" of Bukovina to the bosom of Mother Romania, treated all Bukovynians as second-class people. It was especially bad for the Jews so numerous in the region. In addition to the Romanians, they were exterminated by various bandit groups and Ukrainian self-styled fighters. Most of the Jews were killed, some managed to escape from Bukovina.

It is also impossible to hide the fact that in Bukovina, the so-called. "Bukovynsky kuren", with a total number of 800 people, became famous, like almost all independent formations of the Second World War, for its punitive "exploits". It was the militants of this "kuren" who were engaged in mass executions in Babi Yar near Kiev. And it was "Bukovynsky kuren" that destroyed the Belarusian village of Khatyn. But the majority of Bukovynians did not support the self-styled people.

During the occupation, underground organizations began to appear in Bukovina, most often spontaneously. Since the summer of 1942, the Soviet headquarters of the partisan movement began to send specially trained paratroopers to the Chernivtsi region in order to organize the partisan movement. Soon, partisan sabotage groups began to operate in a number of areas of the region. In 1943, partisans of S.A.Kovpak raided Bukovina. In the spring of 1944, the number of partisan groups being abandoned increased significantly. In total, 1,200 people took an active part in the Bukovyna partisan formations, and in the underground - 900 residents of the Chernivtsi region.

At the end of March 1944 Bukovina was liberated. Approximately 100 thousand Bukovinians were drafted into the Soviet army, 26 thousand of them died or went missing.

Soon after the liberation, UPA groups operated in the Chernivtsi region. Unlike Galicia, there was no mass participation of the local population in the Bandera movement. In total, in 1944-52 in the Chernivtsi region, about 10 thousand people were prosecuted for "banditry", of which 2 thousand surrendered, taking advantage of the amnesty. However, the overwhelming majority of the "bandits and bandits" were deserters from soviet army, persons compromised during the Romanian occupation, and criminals.

In 1944, part of the Romanian population fled to Romania, fearing punishment for cooperation with the occupation authorities. Also fled and "bourgeois elements" of various origins. In 1946, 33 thousand people left Bukovina for Romania. Thus, the ethnic composition of Bukovina has changed dramatically - the Germans have almost completely disappeared, the number of Jews has sharply decreased, and the share of Romanians has decreased.

After the war, the Soviet part of Bukovina developed at a rapid pace. Machine-building and chemical enterprises were created. A network of large instrument-making factories was created, science was actively developing. The population of the city of Chernivtsi increased significantly due to the influx of the rural population from the region and many regions of Ukraine and the entire USSR. In 1959, 152 thousand inhabitants lived in Chernivtsi, and in 1989 - already 256.6 thousand. The geographical boundaries of Chernivtsi also expanded. The city was a large railway junction, an international airport was functioning.

During the Soviet era, the Ruthenian population of Bukovina was mainly Ukrainianized, more precisely, it got used to associating itself with Ukrainians. Many Russian-speaking residents of eastern Ukraine and other republics of the USSR settled in cities, primarily in Chernivtsi. As a result, the Russian language became widespread in the region much wider than in other western Ukrainian regions.

In "independent" Ukraine, the Chernivtsi region is experiencing an economic crisis and depopulation. Mortality exceeds the birth rate, in addition, there is a significant emigration of Bukovyns abroad, (in terms of the number of "migrant workers" Chernivtsi region was the record holder in Ukraine). As a result, the population of the region is decreasing.

Nevertheless, being geographically considered a part of western Ukraine, the Bukovyns are mentally far from it. Unlike Lviv residents, people here are indifferent to Bandera and the history of his "movement". However, in Chernivtsi there is a monument to the “heroes” of Bukovynsky kuren in the form of an angel, spreading its wings wide, ready to cover the “heroes” - punishers with them. But let us note that in Chernivtsi there are preserved “Soviet” streets named after Yuri Gagarin, Arkady Gaidar. Along with nostalgic memories of soviet era in the mentality of the Bukovinian people, the idea of \u200b\u200bthe time of Austria-Hungary as a kind of "golden age" is preserved. It is no accident that in 2008 a monument to the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph was erected in Chernivtsi.

In general, the Ruthenians of Bukovina have not yet become ardent Ukrainians of the Galician type, but at the same time the movement of the Ruthenian renaissance, which developed significantly in Transcarpathia, did not find a strong response in Bukovina either.

Rusyns of South Bukovina

In 1940, only the northern part of Bukovina was annexed to the USSR. The southern part of the region remained part of Romania. Since that time, the ethnic history of the South Bukovinian Rusyns differs sharply from their fellow tribesmen living a little further north. The only thing that the Ruthenians of South Bukovina have in common with the northerners is that they, too, were subjected to Ukrainization.

In 1940, only the northern part of Bukovina was annexed to the USSR. The southern part of the region remained part of Romania. Since that time, the ethnic history of the South Bukovinian Rusyns differs sharply from their fellow tribesmen living a little further north. The only thing that the Ruthenians of South Bukovina have in common with the northerners is that they, too, were subjected to Ukrainization.

The Eastern Slavs are the indigenous inhabitants of the region, and only from the XIII-XIV centuries the Wallachian colonization led to the appearance of the Roman-speaking Wallachians here. From about 1359, southern Bukovina became the center of the Moldavian principality. Gradually, the Romanization of the Slavs took place, which was favored by a single Orthodox faith and very similar life and culture of the Vlachs and Ruthenians. The Romanization of Southern Bukovina was incomparably more effective than Northern. Rusyns in the 19th century became a minority in their native land, and in 1900 they made up about 20% of the population.

During the Austrian census of 1910, 43,000 Rusyns lived in South Bukovina, and at the same time at least 30,000 people living south of Chernivtsi "changed" the definition of their native language from Rusyn to Romanian. Then, for the first time in the entire time of the population censuses in Bukovina, the number of the Rusyn population decreased by 2.5%. Although part of this reduction fell on the Rusyns, who more or less owned romanian thanks to the presence of the Romanian schools, which preserved the Rusyn identity, the processes of assimilation have gone far.

Since 1918, the Romanization of the Ruthenian population has accelerated significantly. The Ukrainian movement, for all its insignificance, managed to play its vile role, splitting the possibility of any cultural and linguistic resistance. However, the Ukrainian leaders who had done their job were also out of work. If in the northern Bukovina all this time the Rusyn-Ukrainian linguistic and cultural environment was still preserved, in the southern one there was none of this. The result was a decrease in the number of Rusyns - in 1930, according to the census, there were 35 thousand of them.

The events of 1940 and the annexation of Northern Bukovina to the USSR took place spontaneously and completely unexpectedly for the population of the region. The Rusyns of South Bukovina were finally cut off from the main Slavic massif of the region.

At the same time, the Ruthenian population of Bukovina has never been completely united in ethnic terms, being noticeably divided into the Ruthenians themselves and the Hutsuls, which retain significant differences from the rest of the population of the region both in territorial terms and in their way of life. A significant part of the population of the mountainous part of Bukovina during the Romanian population census of 1930 chose the ethnonym "Hutsul", rather than "Ukrainian" or "Rusyn". After the territorial division of 1940, a significant part of the Hutsuls appeared on the territory of Romania, now making up about a third of the Slavic population of South Bukovina. Contacts between both groups were significantly hampered for various reasons.

True, after the communists came to power in Romania in 1944, relatively favorable times came for the Rusyns of Southern Bukovina for some time. Ukrainian schools were opened, a teacher training system was created, etc. This, to a certain extent, contributed to the consolidation of Ukrainian identity among the Ruthenians of Southern Bukovina. The number of residents of the region who indicated Ukrainian as their native language reached 7.3%. But under the rule of Ceausescu (1965-89), despite the declaration of the principles of proletarian internationalism, the oppression of national minorities sharply intensified in Romania. In addition, there was an outflow of the rural population (and the overwhelming majority of Rusyns lived in villages) to cities that were almost completely Romanian-speaking. Thus, for the Rusyns, who moved from the village to the city, not only their way of life changed, but also their language, and then their ethnic identity.

After the establishment of a democratic regime in Romania in December 1989, the situation of the Rusyns did not improve. In the Romanian parliament, the Ukrainians (officially, all the eastern Slavs of Romania, except for the Lipovan Old Believers, are considered Ukrainians) are given one seat. At the same time, conflicts between those who consider themselves Ukrainian, Ruthenian or Hutsul lead to the fact that there is no organized movement of Ruthenians in South Bukovina.

The South Bukovinian Rusyns, even calling themselves Ukrainians, do not receive any help from Ukraine. However, Ukrainian self-styled activists are only interested in the Canadian Ukrainian diaspora, from which they expect to receive financial and other support, and they consider it ridiculous to help some peasants in the Carpathian Mountains. But since betrayal is the essence of Ukrainianship, what else can we expect?

At present, there is an intensified Romanization of the Rusyn-“Ukrainians”, which casts doubt on their continued existence in this region. According to the general population census conducted in 1992 in Romania, only about 10 thousand people (1.4%) living in the Suceava county considered themselves to be Ukrainians. A little more, about 14 thousand (2%), have identified Ukrainian as their mother tongue. Despite the small numbers, the very inconsistency of Ukrainians in terms of language and ethnicity raises a number of questions.

Today we can talk about the number eastern Slavs in Romania in 130-140 thousand people. It is problematic to give an exact figure not only because of the position of the Romanian authorities, who are trying to overestimate the number of Romanians, but also because of the difficulties with the self-identification of the Eastern Slavs themselves. In the large (about 6 thousand inhabitants) commune of Darmanesti, which almost completely speaks Ukrainian, only 250 people called themselves Ukrainians. A similar picture developed in other towns and villages of the region.

However, all this does not change the fact of the gradual disappearance of the Russian ethnic element, indigenous to this region, who has lived on its lands for more than one and a half millennia.