4. ABOUT “POEM WITHOUT A HERO”

THIS SECTION WAS COMPLETED BY ME PERSONALLY BASED ON AN ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS LITERARY SOURCES

4.1 FROM NAIMAN A.G.

Akhmatova began writing the Poem at the age of fifty and wrote until the end of her life. In every sense, this thing occupied a central place in her work, fate, and biography.

This was her only complete book after the first five, that is, after 1921, and not on a par with them, but them - like everything that Akhmatova wrote, including the Poem itself - which covered and included them. She skillfully and thoroughly compiled sections of collections that were being prepared for publication and those that were published or fell under the knife, and she was a master of combining poems into cycles.

The poem was for Akhmatova, like “Onegin” for Pushkin, a set of all the themes, plots, principles and criteria of her poetry. Using it, like a catalogue, you can search almost for individual poems of hers. Having begun with a review of what was experienced - and therefore written - it immediately took on the function of an accounting and reporting ledger - or the electronic memory of modern computers - where, recoded in a certain way, "Requiem", "Wind of War", "Rose Hip Blossoms" were "noted" ", "Midnight Poems", "Prologue" - in a word, all the major cycles and some of the things that stand apart, as well as the entire Akhmatova Pushkiniana. Along the way, Akhmatova quite consciously wrote the Poem in the spirit of an impartial chronicle of events, perhaps fulfilling in such a unique way the Pushkin-Karamzin mission of the poet-historiographer.

The poem opens with three dedications, behind which stand three figures that are as concrete as they are generalized and symbolic: a poet of the beginning of the century who died on its threshold (Vsevolod Knyazev); beauty of the beginning of the century, friend of poets, and, implausible, real, disappearing - like hers, and all kinds of beauty (Olga Glebova-Sudeikina); and a guest from the future (Isaiah Berlin), the one for whom the author and her friends raised their glasses at the beginning of the century: “We must drink to someone who is not yet with us.”

For the first time, Akhmatova’s “alien voices” merge into the choir - or, to put the same thing in another way: for the first time Akhmatova’s voice sings in the choir - in “Requiem”. The difference between the tragedy of "A Poem without a Hero" and the tragedy of "Requiem" is the same as between a murder on stage and a murder in the auditorium. Strictly speaking, "Requiem" is Soviet poetry realized in the ideal form that all its demagogic declarations describe. The hero of this poetry is the people: every single one of them participates on one side or the other in what is happening. This poetry speaks on behalf of the people, the poet speaks with them, is part of them. Her language is almost newspaper-like, simple, understandable to the people, her methods are straightforward: “for them I wove a wide cover from the poor words they overheard.” And this poetry is full of love for the people.

What distinguishes it and thereby contrasts it even with ideal Soviet poetry is that it is personal, just as deeply personal as “Clenched her hands under dark veil". It is, of course, distinguished from real Soviet poetry by many other things: firstly, the initial Christian religiosity that balances the tragedy, then anti-heroism, then sincerity that sets no restrictions on itself, calling forbidden things by their names.

And a personal attitude is not something that does not exist, but something that exists and testifies to itself with every word in the poetry of the Requiem. This is what makes “Requiem” poetry - not Soviet, just poetry, because Soviet poetry on this topic should have been state poetry; it could be personal if it concerned individuals, their love, their moods, their, according to the officially approved formula, “joys and sorrows.”

When “Requiem” surfaced in the early 60s after lying at the bottom for a quarter of a century, the impression it gave the public who read it was not at all similar to the usual reader’s impression of Akhmatova’s poems. People - after documentary revelations - needed literature of revelations, and from this angle they perceived Requiem. Akhmatova felt this, considered it natural, but did not separate these poems of hers, their artistic techniques and principles, from the rest.

Then, in the 60s, “Requiem” was included in the same list as samizdat camp literature, and not with the partially permitted anti-Stalinist literature. Akhmatova's hatred of Stalin was mixed with contempt.

4.2. COMMENTARY ON “POEM WITHOUT A HERO”

Anna Akhmatova’s “Poem Without a Hero,” on which she worked for a quarter of a century, is one of the most mysterious works of Russian literature.

Anna Akhmatova really went through everything with her country - the collapse of the empire, the Red Terror, and the war. With calm dignity, as befits the “Anna of All Rus',” she endured and short periods glory, and long decades of oblivion. A hundred years have passed since the publication of her first collection, “Evening,” but Akhmatova’s poetry has not turned into a monument to the Silver Age and has not lost its pristine freshness. The language in which female love is expressed in her poems is still understandable to everyone.

In “Poem without a Hero,” she showed herself exactly what happened to her life when the “hellish harlequinade” of the 13th year swept through. And what can the “Real Twentieth Century” do to a person?

Introduction

While working with materials dedicated to “Poem without a Hero,” one of the most mysterious in Akhmatova’s work, many comments were discovered regarding some particulars, which are explained in great detail. But none of the works contains the concept of the poem. Akhmatova herself responded to numerous requests to explain the meaning of the poem with Pilate’s phrase: “Hedgehog pisah - pisah.” The purpose of this work is not to give further comments on various episodes of the poem, but to, by summarizing what is already known, to recreate the artistic concept of the poem as adequately as possible, which is a new aspect for the study of this work.

It is very difficult for a reader unfamiliar with the era in which the poem was created to understand it, and even the author himself, or the lyrical heroine, does not hide the fact that he “used sympathetic ink” that needed “manifestation.” After all, the imagery of “Poem without a Hero” is full of literary and historical and cultural reminiscences and allusions, personal, cultural and historical associations.

The work also examines the symbolism of the poem: the motif of mirrors, the New Year’s “harlequinade,” biblical motifs, the subtext of epigraphs and remarks. These are all organic components of Akhmatova’s “cryptogram”, which, as proven in the course of the study, work for the concept of the poem.

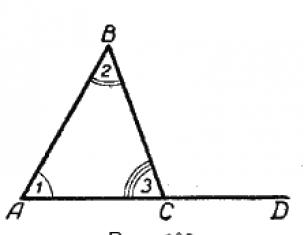

Despite the fact that the chapters and parts of the poem, as well as the introduction and dedications, were created in different time, the poem is a holistic work with a thoughtful structure, which is presented using a diagram.

Three dedications were written for “Poem Without a Hero”: to Olga Glebova-Sudeikina, Vsevolod Knyazev and Isaiah Berlin. The three dedications correspond to the three parts of the poem.

First part. Crime

In the First Part (Petersburg Tale), instead of the expected guests in New Year's Eve to the lyrical heroine “...shadows come from the thirteenth under the guise of mummers.” These masks: Faust, Don Juan, Dapertutto, Iokanaan, symbolize youth lyrical heroine- sinful and carefree. Akhmatova, putting in one row the demonic heroes: Faust, Dapertutto - and the saints: Iokanaan (John the Baptist), wants to show the main sin of the generation - the confusion of good and evil. The sins of a generation are reflected in the dedication itself.

For Akhmatova very great importance had a sensational story in those years of the unrequited love of a young poet, twenty-year-old dragoon Vsevolod Knyazev for the famous beautiful actress Olga Glebova-Sudeikina. Seeing one night that Glebova-Sudeikina was not returning home alone, the young poet shot himself in the forehead right in front of his beloved’s door. The story of Vsevolod Knyazev’s unrequited love for Olga Glebova-Sudeikina is a unique illustration of the spiritual life that was led by the people surrounding Akhmatova (the lyrical heroine) and in which, of course, she herself took part.

The motif of duality runs through the entire poem. The first double of the lyrical heroine in the poem is the nameless heroine, whose prototype is Glebova-Sudeikina:

St. Petersburg doll, actress,

You are one of my doubles.

Second part. Punishment

Akhmatova writes a dedication to Vsevolod Knyazev on December 27, 1940, even before the war, and the second dedication, to Olga Glebova-Sudeikina, was written after the Great Patriotic War: May 25, 1945. Thus, in the Second Dedication and in the Second Part (“Tails”), Akhmatova talks about PUNISHMENT, considering all the cataclysms of the twentieth century: the Russian-Japanese War, the First World War, two revolutions, repressions, the Great Patriotic War - as retribution for all the sins of the generation and for your own sins. But sins committed in youth are difficult to atone for. You can mitigate the punishment through repentance and atonement. And until the lyrical heroine does this, at the mere thought that she may appear before the Last Judgment, she is seized with horror. The poem contains the theme of moral condemnation and the inevitability of punishment.

Akhmatova showed a picture of an inflamed, sinful, merry Petersburg.

The coming upheavals had already appeared through the usual St. Petersburg fog, but no one wanted to notice them. Akhmatova understood that the “prodigal” life of the St. Petersburg bohemia would not remain without retribution. And so it happened.

In the second part, the heroine sees retribution (hence the strange name - “Tails” - back side medals, “Eagle”, which evokes an association with the word “lattice”, which symbolizes the era of repression), atonement for the sins of youth through suffering and persecution: celebrating the New Year of 1941, the heroine is completely alone, in her house “there is no smell of the carnival midnight of Rome.” “The chant of the Cherubim trembles near closed churches,” and this is on the fifth of January according to the old style, on the eve of Christmas Eve - evidence of the persecution of Orthodox Church.

And finally, the heroine cannot create, since her mouth is “smeared with paint” and “filled with earth.” War, just like repression, is the people’s atonement for past sins, according to Akhmatova. The sins of youth, which seemed innocent, weaknesses that did not harm anyone, turned into unbearable suffering for the heroine - pangs of conscience and the consciousness that she would never be able to justify herself. However, a repentant sinner is always given the opportunity to atone for his sins through suffering or good deeds. But more on that in Part Three.

The third part. Redemption

The third and final dedication is addressed to Isaiah Berlin, who visited Akhmatova in 1946 on the eve of his Catholic baptism. That evening, Akhmatova read “A Poem without a Hero” to her guest, and later sent the finished copy. The next day, a listening device was installed in Akhmatova’s apartment. After the meeting with Isaiah Berlin, an employee of the American embassy, a “spy,” according to Stalin, there followed “ civil execution”, the peak of persecution, bullying. This was a time when Akhmatova could not publish her poems, and she was banned from entering all literary societies.

The third part of “Poem without a Hero” (epilogue) is dedicated to the ATONEMENT for the sins of youth through suffering.

Besieged Leningrad also atones for the guilt of its inhabitants. During the blockade, in 1942, the heroine is forced to leave for Tashkent and, leaving, she feels guilty about the city she is leaving behind. But she insists on the “imaginary” nature of their separation, since this separation seems unbearable. The heroine understands that, leaving St. Petersburg, she becomes somewhat similar to the emigrants who so hotly denounced her. (“I am not with those who abandoned the earth...”). Having left the country at the most difficult time, emigrants distance themselves from their homeland, leaving it to suffer and not wanting to share this suffering. Leaving besieged Leningrad, the heroine feels that she is doing the same thing. And here the double of the lyrical heroine appears again. But this is already a double-redeemer, a camp prisoner going for interrogation. The same double says, coming from interrogation, in the voice of the heroine herself:

I paid for myself, neither left nor right

Chistoganom, I didn’t look,

Exactly ten years I walked and I got a bad reputation

Under the revolver, Shelestel.

The epilogue speaks about Russia as a whole, about its atonement for sins during the period of repression, and then in the tragedy of the war. Another, “young” Russia is moving, renewed, cleansed by suffering, “toward itself,” that is, to regain its lost values.

This is how the poem ends.

But instead of who she was waiting for, on New Year’s Eve, shadows from the year 13 come to the author in the Fountain House under the guise of mummers. One is dressed up as Faust, the other as Don Juan. Dapertutto, Iokanaan, northern Glan, the murderer Dorian come. The author is not afraid of his unexpected guests, but he is confused, not understanding: how could it happen that only she, the only one of all, survived? It suddenly seems to her that she herself - the person she was in 1913 and the person she would not want to meet before the Last Judgment - will now enter the White Hall. She forgot the lessons of the talkers and false prophets, but they did not forget her: just as the future matures in the past, so the past smolders in the future.

The only one who did not appear at this terrible festival of dead leaves was the Guest from the Future. But the Poet comes, dressed in a striped verst - the same age as the Mamre oak, the age-old interlocutor of the moon. He does not expect magnificent jubilee chairs for himself, sins do not stick to him. But his poems told about this best. Among the guests is the same demon who sent a black rose in a glass in a crowded hall and who met with the Commander.

In the carefree, spicy, shameless masquerade chatter, the author hears familiar voices. They talk about Kazakov, about the Stray Dog cafe. Someone is dragging a goat-legged creature into the White Hall. She is full of accursed dance and ceremoniously naked. After shouting: “Hero to the forefront!” - the ghosts run away. Left alone, the author sees his looking-glass guest with a pale forehead and open eyes - and understands that gravestones are fragile and granite is softer than wax. The guest whispers that he will leave her alive, but she will forever be his widow. Then his clear voice is heard in the distance: “I’m ready for death.”

The wind, either remembering or prophesying, mutters about St. Petersburg 1913. That year, the silver month cooled brightly over the silver age. The city was disappearing into fog, and in the pre-war frosty stuffiness there lived some kind of future rumble. But then he hardly bothered the soul and drowned in the Neva snowdrifts. And along the legendary embankment, it was not the calendar century that was approaching - the real Twentieth Century.

That year, an unforgettable and tender friend stood over the author’s rebellious youth - a dream he only had once. His grave is forever forgotten, as if he never lived at all. But she believes that he will come to tell her again the word that conquered death and the answer to her life.

The hellish harlequinade of the thirteenth year rushes past. The author remains in the Fountain House on January 5, 1941. The ghost of a snow-covered maple tree is visible in the window. In the howling of the wind one can hear very deeply and very skillfully hidden fragments of the Requiem. The editor of the poem is dissatisfied with the author. He says that it is impossible to understand who is in love with whom, who met, when and why, who died and who remained alive, and who is the author, and who is the hero.

The editor is sure that today there is no need to talk about the poet and a swarm of ghosts. The author objects: she herself would be glad not to see the hellish harlequinade and not to sing amid the horror of torture, exile and execution. Together with her contemporaries - convicts, "stopyatnitsa", captives - she is ready to tell how they lived in fear on the other side of hell, raised children for the chopping block, dungeon and prison. But she cannot leave the path that she miraculously came upon and not finish her poem.

On the White Night of June 24, 1942, fires burned out in the ruins of Leningrad. In the Sheremetevsky Garden, linden trees are blooming and the nightingale is singing. A crippled maple grows under the window of the Fountain House. The author, who is seven thousand kilometers away, knows that the maple foresaw separation at the beginning of the war. She sees her double going for interrogation behind barbed wire, in the very heart of the dense taiga, and hears her voice from the lips of her double: I paid for you with pure cash, I walked under a revolver for exactly ten years...

The author understands that it is impossible to separate her from the seditious, disgraced, sweet city, on the walls of which is her shadow. She remembers the day when she left her city at the beginning of the war, escaping an evil pursuer in the belly of a flying fish. Below she saw the road along which her son and many other people were taken away. And, knowing the time of vengeance, overwhelmed by mortal fear, with dry eyes downcast and wringing her hands, Russia walked ahead of her to the east.

PHOTO FROM THE INTERNET

One of Akhmatova’s most fundamental creations is the Poem without a Hero, which covers various periods of the poetess’s life and tells about the fate of Akhmatova herself, who survived her creative youth in St. Petersburg, the besieged city and many adversities.

In the first part, the reader observes nostalgia and a journey into bygone eras. Akhmatova sees how “deliriums” and bursts of some kind of conversation “resurrect”; she meets “guests” who appear in masks and represent shadows of the previous time.

Most likely, the poetess here seems to be traveling along the waves of memory and describing a situation when a person plunges deeply into images, remembers people with whom he communicated a long time ago and some of whom can no longer be seen on this earth. Therefore, the action takes on the features of a kind of carnival and phantasmagoria. This part ends with the call of a hero who is absent from the poem.

The theme of the presence/absence of the hero is continued by the second part, which describes communication with the editor, who is the only voice of reason in the entire poem and, as it were, returns the reader to the rational world. He asks how there can be a poem without a hero and Akhmatov, it would seem that he begins some kind of reasonable explanation, but then again it seems to return to a dream or some kind of dreams that are far from reality. And here the poetess’s thoughts lead her towards memories not of her own biography and 1913, but towards discussions about culture in general and previous eras.

In the final part, the poetess describes the evacuation from the city, the destroyed country and the hardships of the war. Here the main theme becomes the homeland, the native country, with which the poetess also experienced all sorts of troubles. At the same time, here the poetess talks about the future time, but does not see prospects or anything worthy there; for the most part, Akhmatova’s appeal is directed to past eras, she “came with a distant echo” and wanted to hear such an echo precisely from previous times and her memories.

Of course, one should speculate about who the hero is in this poem and whether there really can be a poem without a hero at all. In fact, the hero is present here to some extent; he can be his homeland, St. Petersburg, and Akhmatova herself. However, if we somehow generalize and try to look at the situation more globally, then the hero of this poem is undoubtedly the stream of consciousness that passes through people, times and countries.

Analysis of the poem Poem without a hero according to plan

You might be interested

- Analysis of the poem On the swing by Feta

The poem “On the Swing” was written by Afanasy Fet in 1890. At that time, the writer was already 70 years old. This work is one of the poet’s gentle, lyrical creations.

- Analysis of the poem Where Tolstoy's vines bend over the pool

The poem by Alexei Tolstoy is a short ballad. It is interesting that the poet initially created a ballad inspired by Goethe’s “The Forest King”. However, Alexey Konstantinovich cut his ballad in half, making the ending open

- Analysis of Derzhavin's poem Nightingale

Derzhavin wrote his work entitled “The Nightingale” in 1794. Although it came out much later, this circumstance did not affect the content of the ode in any way.

- Analysis of the poem Let the dreamers be ridiculed long ago by Nekrasova

The main part of Nekrasov’s love lyrics falls on the period of the middle of his work and, of course, the pearl among all these lyrics remains the so-called Panaevsky cycle, which is a story about an amorous relationship with Avdotya Panaeva

- Analysis of the poem Petersburg stanzas by Mandelstam

Osip Emilievich Mandelstam is a true creator and recognized genius in Russian literature. His poetry is a sigh of lightness and the rhythm of shimmering lines. This work Petersburg stanzas was written in January 1913

At the turn of the century, on the eve of the 1917 revolution, during the First and Second World Wars, the work of A.A. appeared in Russia. Akhmatova, one of the most significant in world literature. As A. Kollontai believed: “Akhmatova wrote a whole book of a woman’s soul.” Anna Andreevna became an innovator in the field of poetry.

In almost all of Akhmatova’s works, Love for the Motherland can be traced. Anna Akhmatova lived a long life, in which there was both happiness and sorrow. Her husband was shot, her son was repressed. The poetess experienced a lot of hardships and grief in her life, but she never parted with her homeland.

“For me, poetry is a connection with time, with new life my people... I am happy that I lived in these years and saw these events...” - this is what Anna Andreevna wrote about her life.

Anna Akhmatova lived in an era of tragic events. The contradictory times left their mark, the poetess became “iron”. She did not want to adapt to circumstances and was independent in her judgment. And this “ironness” became the drama of life.

In Akhmatova’s work, the main place is occupied by “Poem without a Hero.” According to many literary scholars, this work became an innovation in the field of literature: a poetic narrative about oneself, about time, and the fate of one’s generation.

As the poetess herself believed, the poem was “a repository of secrets and confessions.” In this work, Akhmatova combined poetry, drama, autobiography and memoirs, literary studies about the works of people such as Pushkin, Lermontov, Dostoevsky.

During the study of materials written about “The Poem without a Hero,” many different interpretations of this work were discovered. Akhmatova explained the meaning of the poem with a quote from Pontius Pilate: “Hedgehog pisah - pisah.”

The purpose of this work is to summarize famous works and interpreting the text, present your understanding of this poem.

Reading experience

Akhmatova wrote the poem over the course of 25 years, from 1940 to 1965. She did not present the final version of her poem. The work, written on the basis of the author's manuscripts, exists in several editions.

Comparing different editions, one can notice that in later versions epigraphs, new versions of episodes, subtitles, and stage directions appear. These elements are also of interest to the reader. Every detail of the poem invites multiple interpretations.

Akhmatova herself gives an interpretation of “Poem without Heroes.” A triptych is a work consisting of three parts - three dedications to those who died in besieged Leningrad. The structure of the work did not change. The introduction, chapters, dedications, parts of the poem were created in different time periods, “Poem without a Hero” is an integral text with a certain structure that can be presented in the form of a diagram: the first part is crime, the second is punishment, the third is atonement.

In the text “Instead of a Preface,” the author himself explains that there is no need to look for the secret meaning of the work, but to perceive it as it is.

The poem is the poetess’s thoughts about her time, about man’s place in this world, about his purpose and the meaning of life. This is reflected in the epigraph “Deusconservatomnia“The Lord preserves everything.

The title - “Poem without a hero”, is paradoxical in itself and exclusively. It is difficult to give an unambiguous interpretation. After all, there are no poems without a hero.

It was not by chance that Akhmatova put the genre of her work in the title. “A Poem without a Hero” is a kind of lyrical poem in which the lyrical “I” is present. With this technique, Anna Andreevna showed us that she was an eyewitness to the events described. A.V. Platonova notes that it is impossible to determine the genre of “Poem without a Hero.” This is a poem, a drama, and a story.

The poem can even be classified as a mystery or extravaganza. Akhmatova combined biblical motifs and everyday life scenes into the plot.

Interestingly, according to Anna Andreevna herself, the poem “with the help of the music hidden in it twice went into ballet”:

“And in the dream everything seemed to be

I'm writing a libretto for someone,

And there is no end to music...”

This is a kind of performance in which the characters are represented by certain voices: “words from the darkness”, “a voice that reads”, “the wind, either remembering or prophesying, mutters”, “silence itself speaks”, “the voice of the author”

Thus, the poem intersects different genres, forms and types of art.

The titles in the poem consist of levels: the title of the work itself, the subtitle - “Triptych”, the subtitles of the parts. The triptych indicates that the work consists of three parts - “1913”, “Tails”, “Epilogue”.

The first part is subtitled “ Petersburg story", which, according to A.V. Platonova, is associated with “The Bronze Horseman” by A.S. Pushkin. Thus, the researcher draws attention to the synthesis of types of literature, poetry and prose.

Who main character? Researchers such as K. Chukovsky, M. Filkenberg, A. Heit, Z. Esipova and others tried to answer this question. No one could give a definite answer.

In the poem itself the wordhero used twice. In the first part: “Hero to the forefront!” and in the second, “And who is the author, who is the hero...” Nothing else says about his presence in the work. There is not a single name in the poem - only masks, some kind of puppets that someone controls. They can't be heroes.

It is interesting that the poem does not fall apart in the absence of the hero. It traces the time and point of view of the author, the lyrical heroine, who narrates about a certain time and evaluates it. Akhmatova talks to the reader through the poem.

“A Poem Without a Hero” is about a time in which there were no heroes. The destinies of people were controlled by a time when human life had no value.

Epigraphs in the composition “Poems without Heroes” play an important role. These are quotes from poems by various poets or Akhmatova herself. With the help of epigraphs you can see the intertextuality of the work. They lead us to certain ideas of the poem, an understanding of the meaning, and to some extent become elements of dialogue. According to T.V. Tsivyan, by turning to world poetic poetry, the line between “us” and “strangers” is blurred, which brings the poem into the orbit of world poetry.

“A Poem without a Hero” is itself paradoxical due to the fact that there is no connecting hero, they are blurred. Only the Image of the author in “A Poem without a Hero” is the connecting link between the world of characters. L.G. Kikhney notes that the poem is a monologue by the author.

Overall, the first part“Nine hundred and thirteenth year. Petersburg Tale"is the most eventful.The plot is based on the real dramatic story of the poet V. Knyazev and actress O. Glebova-Sudeikina. Love story ended sadly - the young man committed suicide because of his unhappy love for a flighty and fickle actress.

Phantasmagoria is the main theme of the first part.

A special feature of the story was that Akhmatova showed the life of an entire era. People are actors, hiding behind masks, and their life is a masquerade. They only play life, play certain roles:

"Petersburg doll, actor..."

As L. Losev notes, heroes do not pretend to be who they are. Life is like a farce. And the result of this game is death, as payment for participation.

Instead of invited guests, shadows come to the lyrical heroine for the New Year celebration: Don Juan, Faust, Glan, Dorian, Dapertutto, Iokanaan. These heroes symbolize the author's carefree and sinful youth.

The mixture of these images tells us that good and evil are always together, they are inseparable. This is the main sin of the younger generation.

Petersburg in 1913 is also one of the main characters of the work:

“And the carriages fell off the bridges,

And the whole mourning city floated...

Along the Neva or against the current, -

Just stay away from your graves."

1913 is the time of Rasputin, a series of suicides, a premonition of the end of life.

The Neva River is a symbol of the flow of life, “accelerating flight”, moving, carrying with it. And for Akhmatova, this transience of time is most noticeable in St. Petersburg:

“I am inseparable from you,

My shadow is on your walls."

The sad outcome of the first part of the poem is the death of a young man who could not accept the betrayal of his beloved woman, only the beginning of reckoning. It is no coincidence that Akhmatova remembers in besieged Leningrad something “to which she said goodbye long ago.”

In the second part of the poem, the “dissatisfied editor” asks questions about the meaning of the poem, its “incomprehensibility,” understatement, and confusion. And the author, in his attempt to explain, plunges us into the era of romanticism. The ghosts of Shakespeare, El Greco, Cagliostro, Shelley appear. With the help of people's creativity, the author tries to comprehend the past of humanity.

Reflections are interrupted by the remark “The howling in the chimney subsides, the distant sounds of Requiem are heard, some dull groans. It’s millions of sleeping women who are delirious in their sleep,” which brings us back to reality and reinforces the feeling that “Poem without a Hero” is the confession of a lyrical heroine.

Russo-Japanese War, First World War, Revolution of 1905-1907 and the Great October Revolution, repression, Great Patriotic War- this, according to the author, is retribution for the sins of an entire generation. Punishment is inevitable. Atonement and repentance are necessary. And the lyrical heroine is afraid to stand before the “Last Judgment” without repentance and atonement.

“1913” with its plot is reminiscent of Satan’s ball. The theme of the Apocalypse, the premonition of a catastrophe, was widespread at the beginning of the twentieth century:

“And for them the walls opened up,

The lights flashed, the sirens howled,

And the ceiling swelled like a dome...

However

I hope the Lord of Darkness

You didn’t dare to enter here?”

The title of the second part is “Tails” - and this is the other side of the coin. Behind the apparent prosperity there is hidden negativity - arrests, repression. A generation atones for sins through suffering and persecution.

Heroine New Year meets already alone, “there is no smell of the carnival midnight of Rome.” “The chanting of the Cherubim trembles near closed churches” - it’s too late to repent, buy up sins, make excuses.

In 1946, after a meeting with I. Berlin, Akhmatova was persecuted: her poems were not published and she was not accepted into literary societies. At this time she writes the third part - the Epilogue. About the period of atonement for the sins of one’s youth.

Suffering is the main motive. “The city is in ruins... fires are burning out... heavy guns are roaring” - this is how it begins The third part of the poem is the epilogue. There is no place for ghosts here. This is reality.

Leningrad (formerly St. Petersburg) - atones for the sins of its inhabitants.

The heroine leaves for Tashkent. Separation from the city is unbearable for her, she feels guilty, comparing herself with emigrants. Having left for hard times, the heroine feels that she left her hometown to suffer.

Anna Andreevna left part of her life, part of herself, her inner world:

"My shadow is on your walls,

My reflection in the canals..."

If in the first part the lyrical heroine has a double - an actor, then in the third part - a double - a redeemer who comes from interrogation:

“Clean, I didn’t look,

I went for exactly ten years

And I have a bad reputation

Under the revolver, Shelestela."

In “Poem Without a Hero,” the past, present, and future echo:

“As the future matures in the past,

So in the future the past smolders...”

Life is presented as a dream: “I sleep - I dream about our youth...”. And in a dream the author’s whole life is intertwined: “I dream about what is about to happen to us...”.

In all this one can hear echoes of the past, without which the present and future cannot exist. The author briefly recalls his life, an entire generation of a past era.

The motif of time can be traced throughout the entire work. It is fleeting like a dream.Time is history. Personal history. The story of a generation. History of the Motherland.

Akhmatova analyzes the experience of the past in order to understand what could happen in the future with her, with individuals, with Russia. She distributes all the troubles that happen equally, and does not believe that anyone is to blame. Everyone is guilty, everyone is responsible for what is happening: “Am I more to blame than others?”

Memory and conscience bind together all the heroes of “The Poem without a Hero.” All connections are inseparable from each other.

Petersburg in the poem is shown in an animated way, many-sided, changeable, indestructible. St. Petersburg appears in different guises. Then he is common people, common. It is presented as a city of cathedrals, theaters, palaces. That is restless, anxious.

The triplicity of the city’s image shows the disharmony of the events taking place, a certain paradox:

« The wind tore posters from the wall,

The smoke danced squatting on the roof,

And the cemetery smelled of lilacs.

And, sworn by Queen Avdotya,

Dostoevsky and the possessed

The fog was disappearing into the city.”

The last part of the poem - the epilogue - tells in general about Russia, that it is atonement for its sins through repression and wars.

“Dry eyes downcast,

And wringing hands, Russia

walked to the east before me..."

Lines that amaze with their power and significance. After these words it becomes clear that the Motherland is the main character, era, history. And the Motherland that the author spoke about no longer exists.

The architectonics of the “Poem without a Hero” are specific: the fate of an entire era is examined using the example of fate lyrical hero.

The hero’s personal theme develops into a national theme, the theme of Russian history. The associations and epigraphs of the poem lead us to this.

Anna Akhmatova has a presentiment that the sacrifices and losses are not over. A dramatic mood is present at the end of the poem, when the image of the Motherland appears.

The “Epilogue” was written during the Great Patriotic War, a time of great sorrow and pain for an entire people.

The text of the work, due to its rhythm and intonation, is musical and plastic. In all three parts the stanza structure is different. In the first “1913” there is no uniformity; the stanzas resemble unrhymed, torn phrases, like “the whirlwind of Salome’s dance...”. In the second part, the rhythm remains the same, but uniformly numbered stanzas can be traced. “Epilogue” has a strong structure, a clear rhythm that conveys a certain smoothness, fluidity of the events described. This reveals the unique dynamics of the text: from the quickly passing whirlwind of events of 1913 to repressions and echelons, and then to Victory.

The main principle of reading Akhmatova’s work is contextual reading. Here, a big role is given to details - symbols that help to unravel the meaning of the text: “The box has a triple bottom...”.

For example, the stanzas of “Tails”:

“Between “remember” and “remember,” friends,

Distance as from Luga

To the land of satin bouts.”

In Akhmatova’s notes, “bout is a mask with a hood.” The phrase “like from Luga to the country of satin bouts” encodes a very big, huge meaning. That is, remembering and remembering is different concepts. We should not remember the past, but we should remember. This is the main meaning of these lines.

It is noteworthy that at the end of the poemRussia is described as young, purified by suffering, new. She goes in the hope of finding lost values.

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova, like a prophet, foresaw the long-awaited victory, which became a symbol of the end of terrible losses and troubles.

Conclusion

Anna Akhmatova belongs to a generation of writers whose names are associated with the “Silver Age” of Russian poetry. Poets of this movement tried to show the value of the surrounding world, the value of the word.

Akhmatova began writing “Poem without a Hero” at the age of 50, and finished two years later. Then the poem was completed and rewritten over the course of 25 years. During the corrections, the volume of the text almost doubled.

The poem lived with the author, it “reacted” to the reactions of readers:“I hear their voices and remember them when I read the poem aloud...” These are the first listeners of the poem who died during the siege of Leningrad.

Remembering the events of 1913 and the repressions of the 1930s, Akhmatova leads the reader to a turning point for Russia - the Great Patriotic War. The poem begins with the tragedy of a person, a young poet, and ends with the tragedy of an entire people.

In “A Poem without a Hero” there are several subtextual layers, several interconnected themes and motifs can be traced, which represents the main concept of the work.

There is no specific hero, since he exists in an indefinite time. All heroes unite insingle actor- a great country - Russia, the fate of which depends on each of us.

The genre of Anna Andreevna Akhmatova’s work still raises many questions. The poem is considered here not in the narrow sense of the word, but in a broader one. This work reveals a synthesis of genres and arts, which is distinctive feature poems.

You can think about “Poem without a Hero” endlessly, searching for the meaning and details of the work. There are many interpretations of the text of the poem.

In my work I tried to express my own impression of the text. And the fact that the work arouses interest in the reader is undeniable. This suggests that the Poem will live forever, like Time itself, which, as K. Chukovsky believed, is the only hero of the poem.

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine

Vinnitsa State Pedagogical University named after Mykhailo Kotsyubinsky

Department of Foreign Literature

Coursework on foreign literature

ARTISTIC ORIGINALITY OF “POEM WITHOUT A HERO”

ANNA AKHMATOVA

V year students

Institute of Correspondence Studies

specialty "Russian language"

and literature and social pedagogy"

Pecheritsy Zoya Vladimirovna

Scientific director

prof., doctor of philology Sciences Rybintsev I.V.

Posted

INTRODUCTION

1.2 Composition of the poem

SECTION II FEATURES OF ANNA AKHMATOVA'S ARTISTIC SKILL IN “POEM WITHOUT A HERO”

2.2.1 The role of the twentieth century poet in the poem

2.4 Features of the language of Akhmatova’s poem

INTRODUCTION

For today's school, for teenagers in high school, already familiar with great poetic names, from Pushkin to Blok and Mayakovsky, the poetry of Anna Akhmatova is of particular importance. Her very personality, partly even now semi-legendary and semi-mysterious, her poems, unlike any others, filled with love, passion and torment, honed to diamond hardness, but without losing tenderness - they are attractive, and in her youth they are able to stop and enchant everyone, and not only those who generally love poetry, but also completely rational and pragmatic “computer” young men who give preference to completely different disciplines and interests.

But in world literature Anna Akhmatova is known not only as the author of poems about happy love. Often, very often, Akhmatova’s love is suffering, a kind of love and torture, a painful fracture of the soul, painful, “decadent.” The image of such “sick” love in early Akhmatova was both an image of the sick pre-revolutionary time of the 10s and an image of the sick old world. It is not for nothing that the late Akhmatova, especially in her “Poem without a Hero,” will administer harsh judgment and lynching, moral and historical, to him.

In light of the fact that in our literary studies certain topics have not yet been covered or even truly studied, the question of the artistic originality of works is of interest to researchers. Therefore, the topic of our course work « Artistic originality“Poems without a Hero” by Anna Akhmatova” seems relevant.

Research into Anna Akhmatova’s work has been going on for quite some time. However, the poetess’s lyrics have not yet been studied in terms of the artistic originality of her “Poem without a Hero.” Therefore, the observations that will be carried out in the work are characterized by a certain novelty.

In this regard, in this course work we will turn to the question of the artistic originality of “Poem without a Hero.”

The purpose of the course work is to study and describe the artistic originality of “Poem without a Hero” by Anna Akhmatova.

To achieve the goal, it is necessary to solve the following problems:

study the text of “Poem without a Hero” and theoretically - critical material;

study scientific literature on this topic;

collect the necessary material;

make observations and develop methods for classifying the extracted material;

conduct textual and literary analysis of the work;

describe observations and draw the necessary conclusions.

These tasks, which we set to study the artistic originality of Anna Akhmatova’s “Poem without a Hero,” have their own practical significance. The material of this course work can be used in lessons of Russian and foreign literature when studying the works of Anna Akhmatova, and can also be used as entertaining material in extracurricular classes, in individual work with students, in practical classes at universities.

1.1 History of creation and meaning of “Poem without a Hero”

Akhmatova’s most voluminous work, the beautiful, but at the same time extremely difficult to understand and complex “Poem without a Hero,” took more than twenty years to create. Akhmatova began writing it in Leningrad before the war, then during the war she continued to work on it in Tashkent, and then finished it in Moscow and Leningrad, but even before 1962 she did not dare to consider it completed. “The first time she came to me at the Fountain House,” she writes about Akhmatova’s poem, “on the night of December 27, 1940, sending one small excerpt as a messenger in the fall.

I didn't call her. I didn’t even expect her on that cold and dark day of my last Leningrad winter.

Its appearance was preceded by several small and insignificant facts, which I hesitate to call events.

That night I wrote two parts of the first part (“1913”) and “Dedication.” At the beginning of January, almost unexpectedly for myself, I wrote “Tails,” and in Tashkent (in two steps) I wrote “Epilogue,” which became the third part of the poem, and made several significant insertions into both first parts.

I dedicate this poem to the memory of its first listeners - my friends and fellow citizens who died in Leningrad during the siege.

She attached fundamental importance to this Poem (Akhmatova always wrote this word in relation to this work only with a capital letter) [9, 17]. According to her plan (and this is what happened), the Poem was supposed to become a synthesis of the most important themes, images, motifs and melodies for her work, that is, a kind of Summary of Life and Creativity. Some new artistic principles, developed by the poetess mainly during the Great Patriotic War, found expression in it, and among them the most important is the principle of strict historicism. After all, the Poem is highly indebted to the suffering and courage that Akhmatova found in the 30s, becoming a witness and participant in the people's tragedy. The silent cry of the people in the prison lines never ceased to resound in her soul and in her words. “A Poem Without a Hero” took in and, as if in a powerful crucible, melted all this incredible and seemingly overwhelming experience for a poet” [ 9, 17 ].

There are so many levels in this work, and it is so replete with direct and hidden quotations and echoes of the life of the author himself and with all European literature, that it is not easy to understand it, especially since it was published in scattered fragments and many of its readings were based on incorrect or incomplete text . Akhmatova herself categorically refused to explain the Poem, but, on the contrary, asked other people’s opinions about it, carefully collected and even read them out loud, without ever showing her own attitude towards them. In 1944, she stated that “the poem does not contain any third, seventh, twenty-ninth meanings” [1, 320]. But already in the very text of the Poem she admits that she “used sympathetic ink”, that “the box has... a triple bottom”, that she writes in “mirror writing”. “And there is no other road for me,” she wrote, “by a miracle I came across this one / And I’m in no hurry to part with it” [1, 242].

Of course, it is most natural to think that Akhmatova was forced to use “sympathetic ink” for censorship reasons, but it would be more accurate to assume that there was another reason behind this: Akhmatova addressed not only the living, but also the unborn, as well as the inner “I” of the reader, who for the time being kept in his memory what he heard, in order to later extract from it what he had once remained deaf to. And here it is no longer state censorship that operates, but that internal censor that resides in the reader’s mind. We are not always ready or able to perceive the voice of extreme rightness, found “on the other side of hell.”

Akhmatova, closely connected with earthly life, at the beginning of her Path rebelled against symbolism, which, in her opinion, used a secret language. But her inability to write poetry about anything other than her own experiences, coupled with her desire to understand the tragic circumstances of her own life so as to be able to bear the burden of them, led her to believe that her life itself was deeply symbolic. To find the “answer” to her own life, she introduces a whole series of people into “Poem without a Hero” - her friends and contemporaries, most of whom have already died - and in this broad context she brings symbols closer to reality; its symbols are living people with their own historical destinies.

1.2 Composition of the poem

Summarizing her life and the life of her generation, Akhmatova goes back far: the time of action of one of the parts of the work is 1913. From Akhmatova’s early lyrics we remember that an underground rumble, incomprehensible to her, disturbed her poetic consciousness and introduced into her poems the motives of an approaching catastrophe. But the difference in the instrumentation of the era itself is enormous. In “Evening”, “Rosary”, “White Flock” she looked at what was happening from the inside. Now she looks at the past from the enormous heights of life and historical-philosophical knowledge.

The poem consists of three parts and has three dedications. The first of them apparently refers to Vsevolod Knyazev, although the date of Mandelstam’s death has been set. The second is to Akhmatova’s friend, actress and dancer Olga Glebova-Sudeikina. The third has no name, but is labeled “Le jour des rois, 1956” and addressed to Isaiah Berlin [4, 40]. This is followed by the six-line "Introduction":

From the year forty,

I look at everything as if from a tower.

It's like I'm saying goodbye again

With what I said goodbye to long ago,

As if she crossed herself

And I go under the dark arches.

“Nine hundred and thirteenth year” (“Petersburg Tale”), the most significant part of the poem in terms of volume, is divided into four chapters. It begins with the fact that on the eve of 1941 the author is expecting a mysterious “guest from the future” in the Fountain House. But instead, under the guise of mummers, the shadows of the past come to the poet. During the masquerade, the drama of the suicide of the poet Knyazev, who committed suicide in 1913 out of unrequited love for Olga Sudeikina, is played out. He is "Pierrot" and "Ivanushka" ancient tale", she is “Columbine of the tenths”, “goat-legged”, “Confusion-Psyche”, “Donna Anna”. Knyazev’s rival, also a poet, with whose fame he cannot argue, is Alexander Blok, who appears here in the demonic mask of Don Juan But the most important thing is that Sudeikina, this beautiful and frivolous St. Petersburg “doll”, who received guests while lying in bed in a room in which birds flew freely, is Akhmatova’s “double” While this personal tragedy is unfolding along the “legendary embankment.” The Neva is already approaching the “non-calendar Twentieth Century”.

The second part of the poem - "Tails" - is a kind of poetic apology for Akhmatova. It begins with an ironic description of the editor's reaction to the submitted poem:

My editor wasn't happy

He swore to me that he was busy and sick,

Secreted my phone

And he grumbled: “There are three topics at once!

Having finished reading the last sentence,

You won't understand who is in love with whom,

Who met, when and why?

Who died and who remained alive,

And why do we need these today?

Reasoning about the poet

And some kind of ghosts swarm?"

[ 1, 335 - 336 ]

Akhmatova begins to explain how she wrote the poem, and traces her path “on the other side of hell” through shameful silence until the moment when she finds the only saving way out of this horror - the very “sympathetic ink”, “mirror writing” about which already mentioned. This is associated with the awakening of the Poem, which is both its Poem and the romantic poem of European literature, existing independently of the poet. Just as it is visited by the Muse, Dante’s interlocutor, so the Poem could already have been known to Byron (George) and Shelley. This frivolous lady, dropping her lace handkerchief, “squints languidly over the lines” and obeys no one, least of all the poet. When she is banished to the attic or threatened with the Star Chamber, she replies:

"I'm not that English lady

And not Clara Gazul at all,

I have no pedigree at all,

In addition to sunny and fabulous,

And July himself brought me.

And your ambiguous glory,

Lying in a ditch for twenty years,

I won't serve like that yet.

You and I will still feast,

And I with my royal kiss

I will reward you at evil midnight."

The last part of the poem "Epilogue" is dedicated to besieged Leningrad. It was here that Akhmatova expressed the conviction that came to her during the evacuation that she was indissoluble with her city. And here she realizes that her homelessness makes her similar to all exiles.

SECTION II. FEATURES OF ANNA AKHMATOVA'S ARTISTIC SKILL IN “POEM WITHOUT A HERO”

2.1 Theme of Akhmatova’s “Poem without a Hero”

Korney Chukovsky, who published the article “Reading Akhmatova” in 1964, which could serve as a preface to the “Poem,” believed that the hero of Akhmatova’s heroless poem is none other than Time itself [12, 239]. But if Akhmatova recreates the past, calling friends of her youth from the graves, it is only to find the answer to her life. “Tails” is preceded by the quote “In my beginning is my end,” and in the first part of the “Poem”, when the harlequinade rushes by, she says:

How the future matures in the past,

So in the future the past smolders -

A terrible festival of dead leaves.

If we take the “Poem” literally, then its theme could be defined as follows: how time or history treated a certain circle of people, mainly poets, friends of her “hot youth”, among whom she herself was the same as she was in 1913 , and whom she calls her “doubles”. But even for such an understanding it is necessary, together with the author, to actively participate in the reconstruction of past times. She describes how in the winter of 1913 the month was cooling “brightly over the Silver Age”:

Christmastide was warmed by fires,

And the carriages fell off the bridges,

And the whole mourning city floated

For an unknown purpose,

Along the Neva or against the current, -

Just away from your graves.

Akhmatova remembers Pavlova (“our incomprehensible swan”), Meyerhold, Chaliapin. But most importantly, it resurrects the spirit of the era that ended so suddenly and completely with the outbreak of the World War:

The ending is ridiculously close:

From behind the screens, Petrushkin's mask

The coachman dances around the fires,

There is a black and yellow banner above the palace...

Everyone is already in place, who is needed,

The fifth act from the Summer Garden

It blows... The ghost of Tsushima hell

Right here. - A drunken sailor sings.

The stage is equally suitable for staging the personal drama of the suicide of a young man in love, and for demonstrating the cataclysms of the “Real Twentieth Century”.

Akhmatova does not offer us material that is easy to digest. The charm of the words and the supernatural power of the rhythm force us to look for the “key” to the poem: to find out who the people to whom the poem is dedicated really were, to reflect on the meaning of numerous epigraphs, to unravel its vague hints. And we discover that the events described in the first part of "1913" are contrasted with everything that happened later. Because the year was 1913 last year, when the actions of an individual as such still had some meaning, and already starting from 1914, the “Real Twentieth Century” more and more invaded everyone’s life.

The siege of Leningrad was, apparently, the culmination of this century's invasion of human destinies. And if in the “Epilogue” Akhmatova can speak on behalf of all of Leningrad, it is because the suffering of that circle of people close to her during the war completely merged with the suffering of all the inhabitants of the besieged city.

2.2 Faces and characters in “Poem without a Hero” by Anna Akhmatova

2.2.1 The role of the twentieth century poet in “Poem without a Hero”

To find the answer to her existence, Akhmatova, as usual, uses the raw materials of her own life: friends and places familiar to her, historical events, which she witnessed, but now she puts it all into more broad perspective. Taking suicide as the plot for the New Year's performance young poet and by connecting his image with the image of another poet, her close friend Mandelstam, who happened to become the poet of the “Real Twentieth Century” and tragically die in one of the camps invented by this century, Akhmatova explores the role of the poet in general and her role in particular. In 1913, Knyazev could still control his fate at will - he chose to die, and this was his personal matter. The poets of the "Real Twentieth Century", slaves of the madness and torment of their country, were not given a choice - even voluntary death now takes on a different, not narrowly personal meaning. Without meaning to, they personified either the “voice” or the “muteness” of their country. And yet, despite all the suffering, they would not exchange their cruel and bitter lot for another, “ordinary” life.

When Akhmatova says that she feels sorry for Knyazev, her feelings are caused not only by the very fact of the young man’s suicide, but also by the fact that, having disposed of his life in this way, he deprived himself of the opportunity to play that unusual role that lay ahead of those who remained to live:

How many deaths came to the poet,

Stupid boy, he chose this one. -

He did not tolerate the first insults,

He didn't know what threshold

Is it worth it and how expensive is it?

A view will open before him...

[ 1, 334 - 335 ]

This expanded understanding of the role of the poet in the post-1914 era is emphasized in the dedication to Isaiah Berlin, and, apparently, it is precisely this that awaits Akhmatova on the eve of 1941, when she is visited by the shadows of the past.

In the second and third parts of the "Poem" Akhmatova describes the price at which life is given. In “Tails” she talks about that shameful silence that could not yet be broken, because this is exactly what the “enemy” was waiting for:

You ask my contemporaries:

Convicts, "stopyatnits", captives,

And we will tell you,

How we lived in memoryless fear,

How children were raised for the chopping block,

For the dungeon and for the prison.

Blue lips clenched,

Maddened Hecubas

And Kassandra from Chukhloma,

We will thunder in a silent chorus

(We, crowned with shame):

"On the other side of hell we"...

In the “Epilogue,” the hero of the poem becomes Petersburg-Leningrad, a city once cursed by “Queen Avdotya,” the wife of Peter the Great, the city of Dostoevsky. Crucified during the siege, Akhmatova saw him as a symbol of what she meant by the concept of the “Real Twentieth Century.” Just as the role of the poet acquired universal significance, so personal suffering merged with the suffering of the entire city, which reached its limit when its inhabitants slowly died from hunger and cold under fire. But the horrors of war were faced by everyone together, together, and not alone, as during the repressions. Only when the terrible drama began to border on madness, and Akhmatova herself found herself cut off from her city, was she able, having tied all the threads, to break the shameful silence and become the voice of the era, the voice of the city, the voice of those who remained in it, and those who scattered in exile in New York, Tashkent, Siberia. She felt part of her city:

Our separation is imaginary:

I'm inseparable from you

My shadow is on your walls,

My reflection in the canals

The sound of footsteps in the Hermitage halls,

Where my friend wandered with me.

And on the old Volkovo Field,

Where can I cry in freedom?

Above the silence of mass graves.

The poet discovered that she had little in common with the ghosts of 1913 or with the Akhmatova she was at that time. But she shared with them the suffering that awaited them all ahead, the fear that enveloped them and which it was better not to remember, arrests, interrogations and death in Siberian camps, the “bitter air of exile” and the “silence of mass graves” of Leningrad. Comparing the era of the early 10s with the “Real Twentieth Century” that replaced it, she is convinced that life was not lived in vain, because, despite everything, the world lost in 1914 was much poorer than what she found, and as a poet and she became a much larger personality than she was then.

For emigrants who were close to the situation of 1913, it was difficult to assess the significance of the second and third parts of the poem and unconditionally accept the author’s renunciation of the Akhmatova as they knew her many years ago, from Akhmatova - the author of “The Rosary”:

With the one I once was,

In a necklace of black agates,

To the Valley of Jehoshaphat

I don't want to meet again...

2.2.2 Characters of “Poem without a Hero”

Contemporaries, fascinated by Akhmatova’s ability to recreate the atmosphere of their youth, were embarrassed and even upset by the way she “used” her friends [5, 117]. It was difficult for them to see in Olga Sudeikina or, say, Blok symbolic images of that era and at the same time people they knew, not to mention understanding such a complementary pair of images as Knyazev - Mandelstam, or in the strange role of a “guest from future" and the idea that Akhmatova and Isaiah Berlin "confused the Twentieth Century."

It would be very interesting to hear Sudeikina’s own opinion about her role in “A Poem without a Hero,” since most of it was written during her lifetime, although Akhmatova speaks of her as long dead. It is curious that Sudeikina also appears in poems from the cycle “Trout Breaks the Ice” by Mikhail Kuzmin, which Akhmatova certainly knew, since she asked Chukovskaya to bring her this book shortly before she herself read to her on the eve of the war in the Fountain House the first lines of what would later became "A Poem without a Hero." The special rhythm of the poem is close to the rhythm of the “Second Impact” of the Kuzmin cycle, where not only do we meet both Knyazev and Sudeikina, but the former also comes to tea with the author along with others who have long since died (including “Mr. Dorian”), - a scene that echoes the appearance of mummers from 1913 in Akhmatova’s house on New Year’s Eve 1941 [11, 98]. And perhaps it was Kuzmin’s description of Olga Sudeikina in the theater box that helped Akhmatova realize the connection between art and life, which she had previously only vaguely felt:

Beauty, like Bryullov's canvas.

Such women live in novels,

They also appear on screen...

They commit thefts, crimes,

Their carriages are lying in wait

And they get poisoned in the attics.

("Trout Breaks the Ice")

In “Tails” [1, 335] Akhmatova expresses fear that she may be accused of plagiarism, because the “Poem” is full of quotes and allusions to the works of other poets, some of them, like Blok and Mandelstam, were also its characters [13, 239]. In her first dedication to Knyazev and Mandelstam, Akhmatova wrote: “...and since I didn’t have enough paper, / I’m writing on your draft. / And now someone else’s word appears...” [ 1, 320 ].

In “Poem Without a Hero,” Akhmatova seemed to have gained power over the world of symbols and allegories common to all poets, in which they themselves play their symbolic role. Thus, she gains the right to borrow their words and use them in her own way: sometimes the poem is perceived as a response to all those literary judgments that have been made about the author, sometimes, as she herself claims, other people's voices merge with her voice, and her poems sound like an echo someone else's poems. But the most important thing is that, seeing in the friends of his youth not just “natural symbols”, as Dante’s contemporaries appear in his “ Divine Comedy", but also characters allegorical masquerade, in which characters from literature, mythology, history and fairy tales, she eventually creates a series psychological portraits, connecting literature, allegories and symbols with life. Among the hawk moths are Sancho Panza with Don Quixote, Faust, Don Juan, Lieutenant Glan, and Dorian Gray. And as soon as the connection was established between her contemporaries and the heroes of literature, antiquity, folk tale- the sharp boundaries between literature and life blurred. People became symbols, and symbols became people. Their interchangeability is explained not by the existence of some imaginary connection, but by Akhmatova’s insight that Mandelstam and Knyazev are in some sense the same type, sharply opposed to Blok; that she herself and Sudeikina are doubles. We enter the world of dreams:

And in the dream everything seemed to be

I'm writing a libretto for someone,

And there is no end to music.

And a dream is also a little thing,

Soft embalmer. Blue bird,

Elsinore terraces parapet.

Realizing at some level that she and her contemporaries were playing their roles on a stage that was intended for the coming drama of the destruction of their world in 1914, Akhmatova, trying to penetrate deeper into the meaning of what was happening, approaches questions of fate, guilt and comprehension of what lies outside of our usual way of life. The interweaving of times, the mixing of dreams and reality, while confusing at first, soon turns out to be a key technique that allows one to free oneself from the shackles of the usual perception of time and space. From besieged Leningrad we look back to 1913 and look to 1946 and 1957 - 10 years after the meeting that "confused the Twentieth Century" but for which the poet paid with his suffering - a visit that was like myrrh offered to the queen on the eve of Epiphany:

I paid for you

Chistoganom,

I went for exactly ten years

Under the revolver,

Neither left nor right

I didn't look

And I have a bad reputation

She rustled.

[ 1, 342 - 343 ]

The consciousness of guilt depends on the point of view. On the one hand, Sudeikina is guilty of neglecting the suffering of the young cornet; on the other hand, for the way she is, such relationships are natural, and it is absurd to expect anything different from her. And yet you have to pay for everything, and there is no escape from it. The poet says to his friend:

Don't be angry with me, Dove,

What will I touch this cup:

I’ll punish myself, not you.

Reckoning is still coming -

Don't be afraid - I don't sword at home,

Come out to meet me boldly -

Your horoscope has long been ready...

Knyazev’s words in the poem “I’m ready for death” [1, 326] - the same words that Akhmatova heard from Mandelstam in Moscow in 1934 - sound like the ultimate predetermination of fate. And in response to the poet, the words come from the darkness:

There is no death - everyone knows that

Repeating this has become boring,

Let them tell me what they have.

The three heroes about whom she explains to the editor - the poet dressed up as a mile, the sinister Don Juan, the image associated with Blok, and the poet who lived only twenty years - are both guilty and innocent. “Poets generally do not have sins” [1, 328], writes Akhmatova. The question of how it happened that she was the only one left alive entails the following question: why did this happen? Freedom from sin, which the poet-legislators of 1913 were endowed with, does not bring relief from the pangs of conscience. The poet and author are alien to those “who do not cry with me over the dead, / Who do not know what conscience means / And why it exists” [1, 329].

We constantly return to the starting point: the role of the poet in the “Real Twentieth Century” in general and Akhmatova in particular is to defend his rightness. The poet-legislator, sinless on one level, bearing the burden of other people's sins on another, is the creator or exponent of what can overcome death - the Word. This is what makes the poet’s silence something shameful; this is what earned her, the “flying shadow,” an armful of lilacs from a stranger from the future. It is as a poet that she conquers space and time, knows how to understand her contemporaries, and comprehends the world of Dante, Byron, Pushkin, Cervantes, Oscar Wilde. Naming is the bridge that is thrown across space and time and opens the way to another world, where we usually find ourselves unnoticed and where we are all living symbols that “affirm reality.”

If we can talk about the poet’s philosophy, then this poem is Akhmatova’s philosophical credo, it is the prism through which she sees the past and the future. And it is not so important whether we believe, like Akhmatova herself, that her meeting with Isaiah Berlin had consequences on a global scale or not; Do we agree with the role she assigned to Sudeikina, Knyazev and Blok? The creation of a work capacious enough to absorb all her experience and knowledge allowed her to again feel at one with those of her contemporaries from whom she had been separated, connected her with other poets through the inclusion of other people's lines in her text, and freed her from the need to continue searching for an explanation for the mystery of your life. In “Poem without a Hero,” Akhmatova found the answer, recognizing that everything in the world must inevitably be as it is, and at the same time cannot help but change. In its mirror, "The Real Twentieth Century" is not just meaningless suffering, but a strange and magnificent and at the same time cruel and terrible drama, the inability to participate in which is perceived as a tragedy.

2.3 Literary traditions in “A Poem without a Hero” by Anna Akhmatova

Two names appear immediately as soon as we get acquainted with “Poem without a Hero” - the names of Dostoevsky and Blok. Moreover, what is important here is not only direct historical and literary continuity, but also that new idea of the human personality, which began to take shape in the era of Dostoevsky, but was finally formed only in the era of Blok and was picked up and widely used by Akhmatova.

Anna Akhmatova develops her line of attitude towards Dostoevsky and perception of him especially clearly in “A Poem without a Hero.” It is important that Akhmatova’s line of perception of Dostoevsky is clearly intertwined with the line of her perception of Blok. Dostoevsky and Blok are the two poles of this poem, if you look at it not from the perspective of plot and compositional structure, but from the perspective of the philosophy of history that forms the basis of its real content. Moreover, the most important difference is immediately revealed: Dostoevsky “comes” into the poem from the past, he is a prophet, he predicted what is happening now, before our eyes, at the beginning of the century. Blok, on the contrary, is the hero of the day, the hero of this particular era; he is the most characteristic expression in Akhmatova’s eyes of her essence, her temporary atmosphere, her fatal predetermination. This is an important distinction to keep in mind. But it does not prevent Dostoevsky and Blok from appearing in Akhmatova’s poem, mutually complementing, prolonging each other in time and thereby giving Akhmatova the opportunity to reveal the philosophical and historical essence of her work, central to her work.

Dostoevsky is the second Russian writer after Pushkin, who occupied an equally large place in spiritual world late Akhmatova. Blok is her contemporary, he holds an equally significant place, but this is her sore spot, because Blok’s era for Akhmatova did not end with his death, and it is no coincidence that Akhmatova remembers Blok in her Poem. Coming to Akhmatova’s Poem from the past, from the pre-revolutionary era, Blok helps her to better understand a completely different time, to see both connections and differences here.

In addition, the poet is, in Akhmatova’s understanding, an exceptional phenomenon. This is the highest manifestation of human essence, not subject to anything in the world, but in its “willfulness” it reveals those high spiritual values by which humanity lives. In the first part of the poem, a character appears among the mummers who is “dressed up in stripes,” “painted motley and roughly.” [4, 39] What is said about this character further allows us to say that it is in him that the general idea of the poet as a supreme being is captured and revealed - “a being of a strange disposition,” an extraordinary legislator (“Hamurabi, Lycurgus, Solons I can learn from you must"), as a phenomenon of the eternal and irresistible (he is “the same age as the Mamre oak” and “the age-old interlocutor of the moon”). He is a romantic from the beginning, a romantic by nature, by vocation, by the inevitability of his worldview. He “carries his triumph” throughout the world, no matter what, for “Poets are not accustomed to sins at all.” [ 4, 39 ] Next, the Ark of the Covenant is mentioned, which introduces into the characterization of the “poet” the theme of Moses and his tablets - those great covenants that she left ancient history to subsequent generations. So the poet, in Akhmatova’s interpretation, becomes more than just a being higher order, but a mysterious emanation of the spiritual essence and experience of humanity. Hence the strange outfit of the mummer: a striped verst. This is both a purely Russian road sign and a symbolic milestone marking the movement of history; the poet is a milestone on the path of history; he designates with his name and his destiny the era in which he lives.

Under such illumination, Blok appears in the poem, but as a particular implementation of the poet’s general ideas, as an equally lofty phenomenon, but in this case historically conditioned.

And here’s what else is important: in “A Poem without a Hero,” two planes in the perception of both Dostoevsky and Blok intersect, interacting and complementing each other. The first plan is historical (or rather, historical-literary), which makes it possible for Akhmatova to declare herself as a successor of their work, their main topic. The second plane is deeply personal, subjectively human, which allows Akhmatova to see in her predecessors images of living people, with their own passions and oddities of fate.

2.4 Features of the language of Akhmatova’s “Poem without a Hero”

“Akhmatova’s entire narrative in “Poem Without a Hero” from the first line to the last is imbued with an apocalyptic “sense of the end”...

…This pathos of premonition of imminent death is conveyed in the poem by the powerful means of lyricism…” wrote K. Chukovsky [13, 242].

He was right when he spoke about the powerful means of lyricism with which the poem was created. Despite the fact that it is based on the strictly followed principle of historicism, that its true, although not named, hero is the Epoch and, therefore, the poem can be classified as a work of epic appearance, yet Akhmatova remains primarily, and often exclusively, lyricist.

Some of the most characteristic features of her lyrical style are fully preserved in the poem. As in his love lyrics, she widely uses, for example, her favorite techniques of reticence, vagueness and a seemingly unsteady punctuation of the entire narrative, every now and then plunging into a semi-mysterious, permeated with personal associations and nervously pulsating subtext, designed for the reader’s emotional responsiveness and guesswork. In “Tails,” devoted mainly to the author’s reflections on the poem itself, its meaning and significance, she writes:

Akhmatova's poem composition

But I confess that I used it

cute ink,

I write in a mirror letter,

And there is no other road for me, -

Miraculously I came across this

And I’m in no hurry to part with her.

At first impression, the poem seems strange - a whimsical play of the imagination, material reality is fancifully mixed with grotesque, semi-delusional visions, snatches of dreams, leaps of memories, displacements of times and eras, where much is ghostly and unexpectedly ominous.

In the very first dedication to “A Poem without a Hero,” Chopin’s funeral march sounds, it sets the tone for all further development of the plot. Blok’s theme of Fate, which runs through all three parts with a heavy commander’s step, is instrumented by Akhmatova in sharply intermittent and dissonant tones: a pure and high tragic note is now and then interrupted by the noise and din of the “devilish harlequinade”, the stomping and thunder of a strange, as if driven by the music of Stravinsky’s New Year’s carnival ghosts emerging from the long-vanished and forgotten year of 1913. Confusion-Psyche comes out of the portrait frame and mixes with the guests. The “dragoon Pierrot” runs up the flat steps of the stairs - the twenty-year-old who is destined to shoot himself. Immediately the image of Blok appears, his mysterious face -

Flesh that has almost become spirit

And an antique curl above the ear -

Everything is mysterious about the alien.

That's him in a crowded room

Sent that black rose in a glass...

Suddenly and loudly, across the Russian off-road, under the black January sky, Chaliapin’s voice sounds -

Like the echo of mountain thunder, -

Our glory and triumph!

It fills hearts with trembling

And rushes off-road

Over the country that nurtured him...