At her request, a white lily was painted on the fuselage of Litvyak’s plane. “White Lily-44” (according to the plane’s tail number) became its radio call sign. And from now on she herself began to be called “The White Lily of Stalingrad.” Soon Lydia was transferred to the 9th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment, where the best pilots served, then to the 296th IAP.

One day, her own plane was shot down and she had to land in territory occupied by the Germans. She miraculously escaped capture: one of the attack pilots opened fire on the Nazis, and when they lay down, sheltering from the fire, he went down to the ground and took the girl on board.

On February 23, 1943, Lydia Litvyak was awarded the Order of the Red Star for her military services. By that time, on the fuselage of her Yak, in addition to the white lily, there were eight bright red stars - according to the number of aircraft shot down in battle.

On March 22, in the area of Rostov-on-Don, during a group battle with German bombers, Lydia was seriously wounded in the leg, but still managed to land the damaged plane. From the hospital she was sent home for further treatment, but a week later she returned to the regiment. She flew in tandem with squadron commander Alexei Solomatin, covering him during attacks. A feeling arose between the comrades, and in April 1943 Lydia and Alexei got married.

In May 1943, Litvyak shot down several more enemy aircraft and was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. But fate prepared two heavy blows for her at once. On May 21, her husband Alexei Solomatin died in battle. And on July 18 - best friend Ekaterina Budanova.

But there was no time to grieve. At the end of July - beginning of August 1943, Litvyak had to take part in heavy battles to break through the German defense on the Mius River. On August 1, Lydia flew as many as four combat missions. During the fourth flight, her plane was shot down by a German fighter, but did not immediately fall to the ground, but disappeared into the clouds...

War is the prerogative of men. Military aviation – even more so. But, as the experience of World War II shows, there were exceptions to the rules. This story is about one of the most outstanding female pilots - Lydia Litvyak.

The name of this brave pilot, Hero Soviet Union, listed in the Guinness Book of Records. Lydia Litvyak is the most successful Soviet female pilot of World War II. She shot down 14 aircraft and a spotter balloon. At the same time, Lydia Litvyak fought for only eight months. During this time, she flew 168 combat missions and conducted 89 air battles. At less than 22 years old, she died in battle

Girl and sky

Lydia Litvyak was born in 1921 in Moscow, on August 18 - All-Union Aviation Day. Fascinated by airplanes since childhood, the girl was incredibly proud of this fact. At the age of 14, she enrolled in the Chkalov Central Aero Club, and a year later she made her first independent flight. Then she graduated from Kherson flight school, became an instructor pilot and managed to place 45 cadets on the wing before the start of the war.

And in 1937, Lydia’s father was arrested as an “enemy of the people” and shot.

Fighter pilot

With the beginning of the Great Patriotic War 19-year-old Lydia, in love with the sky, signed up as a volunteer pilot. But only a year later, in September 1942, the girl made her first combat flight as part of the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment. It was one of three women's aviation regiments led by pilot Marina Raskova, which were formed by order of Stalin due to large losses of career pilots.

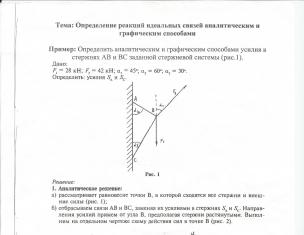

Pilots of the 586th Fighter Wing.

Less than a year later, on February 23, 1943, Lydia Litvyak received one of her first military awards - the Order of the Red Star. By that time, the fuselage of her faithful Yak-1 was decorated with eight bright red stars (a symbol of eight air victories) and a snow-white lily - a special sign of a pilot who is allowed to “free hunt” - a special type of combat operations in which the fighter does not carry out a specific mission to cover bombers, but flies, tracking down enemy aircraft and “hunting” them.

Air ace

In one of the first combat missions over Stalingrad, Lydia managed to shoot down two enemy aircraft - a Ju-88 bomber and a Bf-109 fighter. The Bf-109 pilot turned out to be a German baron, holder of the Knight's Cross, who scored 30 aerial victories. The German was an experienced pilot and fought to the last. But in the end, his car caught fire from a shell fired by Lydia and began to fall rapidly. The pilot jumped out with a parachute and was captured. During interrogation, he asked to show him the person who hit him. Seeing a twenty-year-old girl, the German ace flew into a rage: “Are you laughing at me? I am a pilot who has shot down more than thirty planes. I am a holder of the Knight's Cross! There's no way I could have been hit by this girl! That pilot fought masterfully.” Then Lydia showed with gestures the details of the battle known only to the two of them, he changed his face, took off the gold watch from his hand and handed it to her, the pilot who defeated him...

It was there that Lydia Litvyak received the nickname “White Lily of Stalingrad”, and “Lily” became her radio call sign.

"Different people"

Colleagues said that the sky literally transformed Litvyak: the helm in her hands changed her beyond recognition and seemed to divide her into two completely different people.

“Earthly” Lydia was a silent, modest beauty with blond hair, pigtails and blue eyes. She loved to read books and dress elegantly: she wore unusual things - a white balaclava, a sleeveless vest turned down, chrome boots, a collar for a flight uniform made of fur cut from high boots - and walked with a special gait, causing quiet delight among those around her. At the same time, the blond girl was very reserved about the enthusiastic looks and words of her fellow soldiers, and, what especially impressed the pilots, she did not give preference to anyone.

“Heavenly” Lydia was distinguished by her determination, composure and endurance: she “knew how to see the air,” as her commander said. Her special style of piloting was compared to Chkalov’s, they admired her skill and were amazed at her desperate courage.

Pilot of the 73rd Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment, junior lieutenant Lydia Litvyak (1921-1943) after a combat flight on the wing of her Yak-1B fighter.

On March 22, in the Rostov-on-Don area, Lydia participated in the interception of a group of German bombers. During the battle she managed to shoot down one plane. And then Lydia noticed Messerschmitts flying in the sky. Seeing six Bf-109s, the girl entered into an unequal battle with them, allowing her comrades to complete the task assigned to them. During the battle, Lydia was seriously wounded in the leg, but managed to bring the damaged plane to the airfield. Having reported the successful completion of the mission and two downed enemy aircraft, the girl lost consciousness. According to her colleagues, her plane resembled a colander.

The pilot was credited with extraordinary luck. Once during the battle, Litvyak’s plane was shot down, and she was forced to land on territory occupied by the enemy. When German soldiers tried to take the girl prisoner, one of the attack pilots came to her aid: with machine gun fire, he forced the Germans to lie down, and he landed and took Litvyak on board.

Love and friendship

At the beginning of 1943, Lydia Litvyak was transferred to the 296th Fighter Aviation Regiment and assigned as a wingman to squadron commander Alexei Solomatin (the leading pilot must go on the attack, and the wingman must cover him). After several months of flying together, in April of the same year, literally during a break between battles, the couple got married.

All this time, the girl was friends and fought with the pilot Katya Budanova, with whom fate brought her together at the beginning of her combat journey - in the Raskova women's air regiment - and never separated her. Since then they have always served together and were best friends.

Fatal year

On May 21, 1943, in a plane crash that occurred right in front of her comrades and Lydia herself, her husband, Hero of the Soviet Union Alexei Solomatin, died.

And less than a month later, Lydia’s best friend Katya Budanova received many injuries and died without regaining consciousness. On July 18, in a battle with German fighters, Litvyak and Budanova were shot down. Litvyak managed to jump out with a parachute, but Budanova died.

This fateful year was the last for White Lily herself. On August 1, 1943, Litvyak made her last flight. At the end of July there were terrible battles to break through the German defenses at the line of the Mius River, which closed the road to Donbass. The fighting on the ground was accompanied by a stubborn struggle for air superiority. Lydia Litvyak made four combat missions, during which she personally shot down two enemy aircraft and another in the group. She did not return from the fourth flight. Six Yakovs entered into battle with a group of 30 Ju-88 bombers and 12 Bf-109 fighters, and a deadly whirlwind ensued. Lydia's plane was shot down by a German fighter... In two weeks, Lydia Litvyak would have turned 22 years old.

A search for her was urgently organized. However, neither the pilot nor her plane could be found. Lydia Litvyak was posthumously nominated by the regiment command for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. The front-line newspaper "Red Banner" dated March 7, 1944 wrote about her as a fearless falcon, a pilot who was known to all the soldiers of the 1st Ukrainian Front.

A cruel joke of fate

However, soon one of the previously shot down pilots returned from enemy territory. He reported that he heard local residents say that one day our fighter landed on the road near the village of Marinovka. The pilot turned out to be a blonde girl. A car approached the plane with German soldiers, and the girl left with them.

Most of the aviators did not believe the rumor, but the shadow of suspicion had already spread beyond the regiment and reached higher headquarters. The command, showing “caution,” did not approve Litvyak’s nomination for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, limiting it to the Order of the Patriotic War, 1st degree.

Once, at a moment of revelation, Lydia said to her friend: “What I am most afraid of is being missing. Anything but this.” There were good reasons for such concern. Lida's father was arrested and shot as an "enemy of the people" in 1937. The girl understood perfectly well what it meant for her, the daughter of a repressed man, to go missing. No one and nothing will save her good name. Fate played a cruel joke on her, preparing just such a fate.

Fight, search, find and don’t give up

But they searched for Lydia, searched long and hard. Concerned fans organized their own investigations. In 1967, in the city of Krasny Luch, Lugansk region, schoolteacher Valentina Ivanovna Vashchenko founded the RVS (Reconnaissance of Military Glory) search party. While in the area of the Kozhevnya farm, the guys learned that in the summer of 1943 a Soviet fighter crashed on its outskirts. The pilot wounded in the head was a girl. She was buried in the village of Dmitrievka, Shakhtarsky district, in a mass grave. The study of the remains revealed that the deceased was fatally wounded in the frontal part of the head. Further investigation established that it could only be Lydia Litvyak. The girl was identified by her two white pigtails.

So, 45 years after the death of the pilot, in 1988, an entry appeared in Lydia Litvyak’s personal file: “Died while performing a combat mission.” And in 1990, Lydia was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

At all times, war was considered the destiny of men. And even more so when it comes to combat operations in the sky. And these days you can only meet representatives of the stronger half of humanity on military fighters. The overloads here are literally prohibitive for a person. And the reaction of these professionals should be almost lightning fast, because the time allotted for making a decision is sometimes measured in fractions of seconds. In addition, the pilot must thoroughly study everything specifications your car to know what it is capable of in critical situations.

That is why it is quite difficult to imagine that a sweet, fragile blond girl is sitting at the helm of a high-speed fighter. But nevertheless, given the experience of fighting in the Great Patriotic War, this is possible. During that harsh time, any exceptions were not surprising. One of them is fighter pilot Lydia Litvyak. This will be discussed in this article.

Heroic girl

Looking at the black and white photographs of the war years with Lydia Litvyak, we see a miniature fair-haired beauty in them. It would not be difficult for a girl with such appearance to become a popular actress. And then her fate would have turned out completely differently. Social events, glasses of cold champagne, crispy baskets of caviar and photographers for whom she would pose in fur boas and hung with diamonds would be waiting for her. And this would be quite possible, because Lydia Litvyak looked like Valentina Serova, who was considered the “third great blonde” of the Soviet state after Lyubov Orlova and Marina Ladynina.

However, the fate of our heroine turned out completely differently. She had her own list of victories, but not on the stage or on the silver screen. Lydia Vladimirovna Litvyak made 168 combat missions during the 8 months of her heroic service in Soviet aviation. At the same time, she fought with enemy fighters 89 times, shot down 11 German aircraft and one spotter balloon. So impressive is the list of victories of the most charming and feminine pilot of the USSR, who defended the country during the Great Patriotic War. And this is when many men, while at the controls of their fighters, during the entire period of combat testing were unable to shoot down a single enemy aircraft or, at best, only one or two.

Ace pilot from the USSR Lida Litvyak achieved several group and dozens of individual victories. The young girl, who looked like a fragile student, had a spectacular and aggressive style of air combat. This allowed her to enter the lists of the elite combat aviation that was part of the anti-Hitler coalition.

Biography

Lydia Vladimirovna Litvyak was born in Moscow on August 18, 1921. Subsequently, she was incredibly proud that her birthday coincided with All-Union Aviation Day. For some reason the girl didn't like her name. That is why everyone at home, as well as close friends, called her Lilya or Liliya. Under this name she subsequently went down in history.

Lydia (Lilia) Litvyak was madly in love with airplanes and the sky. However, in those years this did not surprise anyone. On the contrary, it was quite natural that a simple Soviet girl dreamed not of a career as a movie star, but of OSOAVIAKHIM. After all, the party and government of the USSR sought to attract young people to aviation.

Lydia Litvyak kept pace with her era. She easily and completely consciously exchanged playing with dolls for a flight club, and dresses and high-heeled shoes for a flight helmet and overalls. The girl was not only fascinated by the sky. She sought to master this. That is why, at the age of 14, she became a member of the Central Aero Club. Chkalova. At first, the parents knew nothing about this. But it was impossible to hide the intense interest in such an unusual profession for a woman for a long time. A year later, at the age of 15, the girl took to the sky for the first time on her own.

After graduating from school, Lydia Litvyak entered a geology course, after which she was sent to the Far North and then to the south. Here she returned to flying.

Lydia (Lilia) Litvyak became a cadet at the Kherson Flight School. This educational institution she graduated successfully. After that, she became an instructor pilot and managed to train 45 cadets before the start of the war with the Nazis. Colleagues said that she had the ability to see air.

Family

Where Lydia Litvyak’s parents are from is not completely known. After civil war they moved from the village to Moscow. The girl’s mother’s name was Anna Vasilyevna, but history is also silent about who and where she worked. It is only known that the woman was either a dressmaker or worked in a store. The father of pilot Lydia Litvyak is briefly mentioned in all sources, as is her mother. There is only information that his name was Vladimir Leontievich, and his place of work was the railway. In 1937, Lydia Litvyak’s father was arrested on a false denunciation and then shot. Of course, the girl didn’t tell anyone about this. In those years, the status of the daughter of an enemy of the people could radically change her fate. And this was not what the 15-year-old girl, who was literally raving about aviation, wanted at all.

Fateful decision

The biography of pilot Lydia Litvyak developed in such a way that she had to take part in hostilities. After all, her homeland was attacked by an enemy. However, she did not get to the front right away. Soviet authorities they did not want to allow young Komsomol girls into the ranks of the regular troops. They could only be there as nurses. However, life made its own adjustments.

Many girls dreamed of getting to the front line. This required a decision from the Commander-in-Chief himself. This is what she achieved. This pilot was one of the first three women awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Raskova flew to extreme conditions and set records in the sky. Her qualifications, experience and energy have given her authority in air force. Thanks to this, the famous pilot was able to personally ask Stalin for permission to form female combat units. It was useless to resist the brave girls. In addition, the Soviet army carried huge losses not only on the ground, but also in the air. That is why in October 1941, the formation of three women’s air regiments began at once. From the first days of the war, pilot Lydia Litvyak (her photo is posted below) tried to get to the front.

After she learned that Marina Raskova had begun to form women’s air regiments, she immediately achieved her goal. However, the girl had to cheat. She added 100 hours to her flight time, thanks to which she was enrolled in the fighter regiment under number 586, which was headed by Marina Raskova herself.

Fighting character

An enterprising and energetic pilot appeared in Soviet aviation. Lydia Litvyak was distinguished by a somewhat capricious character. Her penchant for taking risks was first noticed during training, when the women's air regiment was based near Engels. Here one of the planes crashed. In order to get into the air, he needed a spare propeller. However, this part could not be delivered. At this time, flights were prohibited due to a snowstorm. But this did not stop Lydia. She voluntarily, without receiving permission, flew to the scene of the accident. For this I received a reprimand from the head of the aviation school. But Raskova said that she was proud to have such a brave student. Most likely, the experienced pilot saw her own character traits in Litvyak.

But Lida’s problems with discipline sometimes manifested themselves in a completely different area. So, one day she made a fashionable collar for her overalls. To do this, she had to cut the fur off the high boots. In this case, she did not wait for Raskova’s leniency. Lydia had to sew the fur back.

Nevertheless, the girl did not lose her love for various accessories even at the front. She cut scarves using parachute silk and altered balaclavas, which in her skillful hands became more elegant and comfortable. Even while under fire, Lida was not only an excellent fighter, but was also able to remain an attractive girl.

But as for the level of aerobatics, there were no complaints about Litvyak. Together with the other girls, she perfectly withstood the accelerated pace of training, which included daily twelve-hour training. The severity of the preparation was explained quite simply. The pilots would soon have to engage in battle with an enemy who was smart and unforgiving of mistakes. Upon completion of her training, Lydia Litvyak passed the piloting of the “hawk” (Yak aircraft) with flying colors, which allowed her to go to war.

The beginning of a combat biography

Being part of the 586th Air Regiment, Lydia Litvyak (photo below) first took to the skies in the spring of 1942. At this time, Soviet troops were fighting in Saratov. The task of our aviation was to protect the Volga from German bombers.

In 1942, pilot Lydia Litvyak made 35 flights from April 15 to September 10, during which she carried out patrols and escorted transport aircraft carrying important cargo.

Battle of Stalingrad

The aviation regiment, which included fighter pilot Lydia Litvyak, was transferred to Stalingrad on September 10, 1942. In a short period of time, the brave girl rose into the sky 10 times. During her second combat flight, which took place on September 13, she was able to open a personal combat account. First, it shot down a Ju-88 bomber. After this, the girl rushed to the rescue of her friend Raya Belyaeva, who had run out of ammunition. Lydia Litvyak took her place in the battle and, as a result of a stubborn duel, destroyed the Me-109. The pilot on this plane was a German baron. By that time, he had already won 30 victories in the sky and was a holder of the Knight's Cross. Being captured and being interrogated, he wanted to see the one who defeated him in the sky. A blue-eyed, fragile, gentle blond girl came to the meeting. The German felt that the Russians were mocking him. But after Lydia, with the help of gestures, showed the details of the battle known only to the two of them, the baron took off the gold watch from his hand and handed it to the girl who had overthrown him from heaven.

On September 27, the brave pilot, being only thirty meters from the Yu-88, was able to hit the enemy vehicle.

And even while participating in combat operations, the pilot allowed herself to misbehave. Having completed a successful combat mission , with fuel in the tank, before landing at her home airfield, she performed aerobatic maneuvers over it. Such jokes were one of her business cards. The regiment commander did not punish her for such entertainment, because the girl successfully performed combat missions, showing good drive, mental tenacity and excellent tactical thinking. After the Battles of Stalingrad, she became an experienced fighter pilot, having been hardened by fire. In addition, on December 22, 1942, the girl was awarded a government award. It was the medal “For the Defense of Stalingrad”.

White Lily

The biography of Lydia Litvyak is described in many books. In the same sources you can find interesting stories about the brave pilot. So, according to some statements, after she won German ace, a large white lily was painted on her hood. They also say that some enemy pilots, seeing this flower, avoided battle. They also say that after each battle in which she managed to shoot down an enemy car, Lydia Litvyak painted one white lily on the fuselage of her Yak. The name of her favorite flower became the pilot’s call sign. In addition, many called Lydia Vladimirovna Litvyak the White Lily of Stalingrad.

Miraculous Rescue

For the first time, the Germans managed to shoot down Lydia Litvyak’s plane shortly after the end of the Battle of Stalingrad. The girl almost died after making an emergency landing. Enemy soldiers immediately rushed towards her. Lydia jumped out of the cabin and began to fire back at the Germans. However, the distance between her and her enemies was steadily shrinking. Litvyak had the last cartridge left in the barrel when the Soviet attack aircraft with whom she was on a mission flew over her. The “Ilys” pinned the Germans down with their fire, and one of them glides not far from the girl and, lowering its landing gear, lands. Lydia quickly climbed into the cockpit with the pilot, and they safely escaped the chase.

New appointment

Fighter pilot Lydia Litvyak - the White Lily of Stalingrad - was transferred to the 437th Aviation Fighter Regiment at the end of September 1942. However, the female link that was part of it did not last long. Its commander, Senior Lieutenant R. Belyaeva, was soon shot down by the Germans, and she had to undergo long-term treatment after a parachute jump. After this, M. Kuznetsova was out of action due to illness. There were only two female pilots left in the regiment. This is L. Litvyak, as well as E. Budanova. They were able to achieve the highest results in the battles. And soon the White Lily of Stalingrad, Lydia Litvyak, shot down another enemy plane. It turned out to be Junkers.

Starting from October 10, the pilots came under the operational subordination of the 9th Guards Regiment fighter aircraft. Lydia Litvyak already had three destroyed enemy aircraft to her credit. One of them was shot down by her personally from the period when she joined the regiment of Soviet ace pilots.

During this period, the girls had to cover the strategically important front-line center - the city of Zhitvur, and also accompany transport planes. In carrying out this task, Lydia flew 58 combat missions. For her courage and excellent execution of command orders, the girl was enrolled in a group of “free hunters” who monitored enemy planes. While at the forward airfield, Litvyak took to the skies five times and fought the same number of air battles. In the 9th Guards IAP, the girls significantly improved their skills.

New victories

On January 8, 1943, the girl was transferred to the 296th Aviation Fighter Regiment. Already in the same month, Lydia accompanied our attack aircraft 16 times and covered ground troops Soviet army. On February 5, 1943, Sergeant L.V. Litvyak was nominated by the command to the Order of the Red Star.

A new victory awaited Lydia on February 11. On this day, Lieutenant Colonel N. Baranov led four fighters into battle. Litvyak distinguished herself by personally shooting down a Ju-88 bomber, and then, as part of a group, she managed to emerge victorious in a battle with an FW-190 fighter.

Wound

The spring of 1943 was marked by calm on almost the entire front line. However, the pilots continued to fly combat missions, intercepting German aircraft and covering Soviet bombers and attack aircraft.

In April 1943, Lydia was seriously wounded. This happened during a rather difficult battle. On April 22, the brave pilot, being part of a group of Soviet aircraft, intercepted 12 enemy Ju-88s, one of which she managed to shoot down. Here, in the sky above Rostov, she was attacked by the Germans. The enemies managed to damage the girl’s plane and wound her in the leg. After the battle, Lydia barely flew to her home airfield, where she reported on the successfully completed task. After this, the girl lost consciousness, falling from blood loss and pain.

However, Lydia did not stay in the hospital for long. Having recovered a little from the injury, she wrote a note that she would go home to Moscow, where she would continue to receive treatment. However, the relatives did not wait for the girl. A week later, Lydia returned to her regiment.

On May 5, not having fully recovered from her injury, Litvyak made another combat mission. Its task was to escort bombers heading to the Stalino area. Our planes were spotted by enemy fighters and attacked by them. A battle ensued, in which Lydia was able to shoot down an Me-109 fighter.

The only love

In the spring of 1943, a new page was written in the biography of pilot Lydia Litvyak. During this period, fate brought the girl together with Alexei Solomatin. He was also an excellent fighter pilot. Romances often began during the war. The acquaintances were quick, and the feelings were stormy. However, most of these novels, for obvious reasons, were short-lived and had an unhappy ending.

In the spring of 1943, there was a short break in hostilities. It was the calm before the battle near Kursk. And in these few weeks of peace, ordinary human happiness came to Lydia. Solomatin and Litvyak got along well in character. Fellow soldiers noted that they were a wonderful couple. Senior Lieutenant Solomatin was initially the girl’s mentor, and then became her husband. However, the happiness of the young people was short-lived. On May 21, 1943, Alexey died. He, being mortally wounded in battle, was unable to land his plane and died in front of his beloved and everyone who was at the airfield. At her husband's funeral, Lydia swore an oath to avenge his death.

Soon, Litvyak’s best friend, Ekaterina Budanova, also died. The girl, who lost two of her closest people in just a few weeks, was left with only combat skills, an airplane and a desire for revenge.

Continuation of hostilities

After some lull the fighting was resumed. And the ace girl, who was only 21 years old, continued to actively participate in them.

At the end of May, in the sector of the front where her regiment operated, the Germans very effectively used a spotter balloon. This “sausage” was covered by fighters and anti-aircraft fire, which repelled all attempts to destroy it. Lydia managed to solve this problem. The girl took off on May 31 and, walking along the front line, went deeper into the territory occupied by the enemy. She attacked the balloon from the rear of the enemy, approaching it from the direction of the sun. Litvyak's attack lasted less than a minute. The pilot’s brilliant victory was marked with gratitude from the Commander of the 44th Army.

Summer fights

July 16, 1943 Lydia Litvyak was on her next combat mission. There were six Soviet Yaks in the sky. They got involved in a battle with 30 Junkers and 6 Messerschmitts, which were trying to strike at the location of our troops. But Soviet fighter pilots thwarted the enemy's plan. In this battle, Lydia Litvyak shot down a Ju-88. It also shot down an Me-109 fighter. However, the Germans also knocked out Lydia’s Yak. The fearless girl, pursued by the enemy, managed to land the plane on the ground. Soviet infantrymen watching the battle helped her break away from the German pilots. Lydia was slightly wounded in the shoulder and leg, but she categorically refused hospitalization.

On July 20, 1943, the command nominated junior lieutenant L.V. Litvyak for another award. The heroic girl received the Order of the Red Banner. By this time, her service record included 140 combat missions and 9 aircraft shot down, 5 of which she destroyed personally and 4 as part of a group. An observation balloon was also mentioned here.

Last Stand

In the summer of 1943, Soviet troops tried to break through the enemy’s defenses, entrenched on the banks of the Mius River. This was necessary for the liberation of Donbass. Particularly heavy fighting took place from the end of July to the beginning of August. They involved both ground and air forces.

On August 1, Lydia Litvyak took to the skies 4 times. During these sorties, she shot down 3 enemy aircraft, two personally, and one while part of a group. Three times she returned to her home airfield. The girl did not return from her fourth combat mission.

It is quite possible that the emotional stress of a hard day or physical fatigue contributed to what happened. Or maybe the weapon simply failed? But be that as it may, the pilots were already returning to their home airfield when they were attacked by eight German fighters. A battle ensued, during which our pilots lost sight of each other, finding themselves in the clouds. As one of them later recalled, everything happened suddenly. A Messer emerged from the white veil of cloud and fired a burst at our Yak with tail number “22”. The plane immediately seemed to fail. Apparently, near the ground, Lydia tried to level it.

Our fighters did not see any flashes either in the sky or on the ground. This is what gave them hope that the girl remained alive.

On the same day, German fighter pilot Hans-Jörg Merkle also went missing. However, there was no information about who shot down this ace. There is a possibility that his death was Lydia Litvyak's parting blow.

Both planes disappeared near Shakhtersk, near the village of Dmitrovka. There is a version that Lydia went on the attack purposefully, eager to avenge the death of her husband and friend. How everything really happened is not known for certain. However, such an act was quite in the spirit of this girl.

Two weeks later, Lydia Litvyak would have turned 22 years old. Afterwards, her relatives said that in one of her letters she told them about a dream in which her husband, standing on the opposite bank of a fast river, called her. This indicated that the girl foresaw her death.

But fellow soldiers, who had not lost hope of seeing the pilot alive, immediately organized a search for her. However, they were never able to find Lydia. And after Sergeant Evdokimov, the only one who knew the crash sector of her Yak, was killed in one of the battles, the official search was stopped. It was then that the regiment command posthumously nominated fighter pilot Lydia Litvyak to the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. However, the posthumous award did not happen. The fact is that soon the previously shot down pilot returned from the territory occupied by enemy troops. According to him, local residents told him that they saw a Soviet fighter land near the village of Marinovka. A short blond girl came out and got into a car that pulled up to the plane with German officers. However, the aviators did not believe such a story, continuing to find out the fate of Lydia. Nevertheless, rumors about the girl’s betrayal reached higher headquarters. And here the command showed caution. It did not approve Litvyak’s submission to highest rank country, but was limited to the Order of the Patriotic War, 1st degree.

However, they continued to search for Lydia. In the summer of 1946, Ivan Zapryagaev, being the commander of the 73rd IAP, sent several people to the village of Marinovka. However, the girl’s fellow soldiers never managed to find out anything about her fate.

In 1971, the search for the brave pilot was resumed by young trackers from the city of Krasny Luch. And only in 1979 they finally found traces of Lydia Litvyak. Residents of the Kozhevnya farm told the children that in the summer of 1943, our fighter plane crashed not far from it. The pilot, who was a woman, was shot in the head. She was buried in a mass grave. This pilot turned out to be Lydia Litvyak. This was confirmed upon further investigation. The grave of Lydia Litvyak is located in the Shakhtarsky district, in the village of Dmitrovka. Here the brave pilot is buried along with other unknown fighters.

In 1988, a monument to Lydia Litvyak was erected in this place. Veterans of the regiment in which the brave pilot served asked to renew the petition to posthumously award her the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Years later, justice prevailed. In May 1990, the President of the USSR signed a Decree according to which Lydia Litvyak became a Hero of the Soviet Union.

Memory

The name of Lydia Litvyak can be found in the Guinness Book of Records. She was listed here as a female pilot who achieved the most a large number of victories in its air battles. In addition, a monument to the brave pilot was erected in the central square of the city of Krasny Luch. It is located opposite gymnasium No. 1, which bears her name.

You can find the name of Lydia Litvyak in “Storm Witches”. This is an anime that tells the viewer about the fight against robotic machines that are trying to take over our planet. It is quite difficult to destroy such an enemy. After all, any deadly weapon, fast missiles, and even innovative technologies. This is what allows insensitive and insidious machines to win victory after victory. Only girls endowed with magical abilities and using vehicle, which is a kind of hybrid of a combat aircraft and a witch's stupa. One of these girls is Sani Litvyak.

Anyone who wants to get acquainted with the biography of the heroic pilot is recommended to look at her documentary. It is called “Roads of Memory” and was directed by E. Andrikanis. In addition, the film “Lilya” is dedicated to the brave pilot. He appeared first in the documentary series “The Beautiful Regiment”. It was filmed in 2014 by director A. Kapkov.

In 2013, viewers were presented with the series “Fighters”. This is the work of director A. Muradov. One of the heroines of the film is Lydia Litovchenko. The image presented by actress E. Vilkova is collective. Lydia Litvyak served as an example for him. The film turned out to be simply wonderful.

The German ace could not believe that he was shot down by a woman

Against the backdrop of the entire war, with its many heroes, the feat of fighter pilots stands out especially. Despite the apparent simplicity and even similarity of their biographies, their destinies contain eternal questions: what fueled their high principles, what ideals did these weak, strong women take with them?

At the beginning of September 1942 at the airfield of the city of Engels Saratov region There were quick gatherings, which, like many things in the war, were shrouded in secrecy. Eight brave girls, trained as fighter pilots, were preparing to fly into the thick of the war - to the Stalingrad front.

Hundreds of volunteers besieged the building in which the commission met. Each of the girls had a separate conversation. In Engels, the already well-known pilot, Hero of the Soviet Union, Maria Raskova, formed three flight regiments. One of them is a fighter aviation regiment. Among those enrolled were Raisa Belyaeva, Ekaterina Budanova, Klavdiya Blinova, Antonina Lebedeva, Liliya Litvyak, Maria Kuznetsova, Klavdiya Nechaeva and Olga Shakhova, who in the fall of 1941 joined the women's aviation unit of M. Raskova in Moscow. Girls who not only graduated from pilot schools, but also became flight instructors themselves. Photos of some of them appeared on the pages of newspapers and magazine covers - they took part in the famous air parades.

They were children of a great era - tragic and heroic. The passion for aviation became one of the brightest phenomena of those years.

In the 1930s, a wide network of flying clubs was created in the country. And after their work shift, young people rushed to the airfields. Pilot and writer Antoine de Saint Exupéry wrote about the romance of air flights: “The most important thing? These are, perhaps, not the high joys of the craft and not the dangers, but the point of view to which they raise a person.” For many flying club cadets, interest in aviation was connected, no matter how pretentious it may sound today, with a sincere need to serve the Fatherland.

Maria Kuznetsova told me about how their training took place in Engels: “We started by digging dugouts ourselves in which to live. Before the war, we flew low-speed U-2 aircraft. Now we had to master the Yak-1 fighters. We studied 12-14 hours a day. On the ground they studied the plane down to the last screw. We had experienced instructors. One after another, they began to fly fighter jets. They conducted training air battles, experiencing heavy overloads. When we came out of the dive, the body seemed to be filled with lead. But we tried to master aerobatic techniques as best as possible, clearly understanding that this is precisely what the skill of a fighter pilot is associated with.”

“We were given only a few months to study,” recalled Klavdiya Blinova-Kudlenko. – The Sovinformburo reports brought difficult messages. Our troops were retreating. We knew that there were not enough pilots at the front, and we were eager to fight. Believe it or not, anxiety for the fate of the Fatherland was then more important to us than our own lives. In the summer of 1942, we had already begun to make combat flights: German planes began to appear in the skies over Saratov. On “Yaks” we guarded residential areas, defense factories, and the bridge over the Volga.”

Lilia Litvyak (on the picture) was a Muscovite. She lived with her mother and younger brother on Novoslobodskaya Street. From a young age she was interested in aviation. She took a course at the flying club and graduated from the Kherson pilot school. In May 1941, Samolet magazine named her among the best instructors of Moscow flying clubs. Everyone who knew Lilia Litvyak remembers her passion for poetry, how she carefully copied the poems she liked into thick notebooks. She sang in the air, although her voice could not be heard over the noise of the engine. But there was joy in living and joy in flying.

Lyrical sincerity and perseverance to the point of exhaustion in work were naturally combined in her character.

Inna Pasportnikova-Pleshivtseva, a former mechanical technician, told me: “At the first glance at Lilya, it was difficult to imagine that in the air she would become a brave fighter. This beautiful girl looked fragile, tender, feminine. I took care of my appearance. Her blond hair was always curled. I remember we were given fur high boots, at night Lilya cut off the trim on them and, making a fashionable collar from it, sewed it onto the flight jacket. In the morning at the formation, Maria Raskova made a stern reprimand to her. But she also knew something else: this girl has a strong-willed character.

You should have seen how persistently she mastered the new technique! With what ease did she take the exhausting overloads associated with flying a fighter!

In her letter to her family there is no trace of fatigue or doubt. She writes to her mother and younger brother: “You can congratulate me - I flew out on my own on a Yak with an excellent rating.” My old dream came true. You can consider me a “natural” fighter. I’m very pleased...”

Ekaterina Budanova was born and raised in the village of Konoplyanka Smolensk region. The family lost their father early. WITH early age Katya took on any job to help her family - she hired herself out as a nanny, worked in other people's gardens. Arriving in Moscow, she learned the profession of a mechanic and worked at an aircraft factory. I came to the flying club. Yesterday's farmhand was literally captured by the romance of aviation. Katya Budanova, at her request, was sent to the Kherson pilot school. So flying became her profession. She worked as an instructor at the Central Aero Club named after V.P. Chkalova. Shortly before the war, she wrote to her mother: “I fly from morning to night. This summer I’m thinking of training 16 pilots for the Red Army.”

In 1941, during the formation of the women’s aviation unit, Maria Raskova said about her: “We already have such wonderful pilots as Katya Budanova.”

The same Inna Pasportnikova-Pleshivtseva said: “Katya Budanova tried to look like a boy in appearance. Tall, strong, with a firm gait, wide, sweeping gestures. A forelock was visible from under his cap. They jokingly called her Volodka. In the evenings, during rest hours, she said: “Let’s sing, girls!” She had a beautiful, strong voice. Katya knew many folk songs and ditties. She was cheerful and passionate."

From Engels, Katya wrote to her mother: “Mom, dear mother! Don’t be offended by me for flying to the front without your permission. My duty and my conscience oblige me to be where the fate of the Motherland is being decided. I kiss you warmly, say hello to your sister Olya. Katyusha."

On September 10, 1942, eight female fighter pilots flew towards Stalingrad in their Yaks-1. From a distance they saw clouds of smoke from the burning city rising into the sky. They landed at a field airfield, which was located on the left bank of the Volga. The front line is just a few minutes away from the summer.

Klavdiya Blinova-Kudlenko recalled how at the airfield they heard skeptical remarks: “They were waiting for reinforcements, but they sent us girls. This is a front, not a club.” “We weren’t offended. We believed in ourselves. In the air we will show: it was not in vain that they entrusted us with the Yaks.”

It was a cruel time. The fighting in Stalingrad took place on the ground and in the air.

Air combat is a serious test even for a seasoned fighter. Not every male aviator is capable of becoming a fighter pilot.

“In the cockpit of a fighter, you are alone in three persons,” Klava Blinova-Kudlenko told me. – The pilot pilots the plane, and at the same time he is both the navigator and the gunner. The battle in the sky is moving fast. The pilot's reaction must be immediate. You turn your head 360 degrees. Everything you can must be invested in these seconds”...

In the very first days, Lilia Litvyak surprised everyone. Downed German planes immediately appeared on her account. There remains a description of the battle in which she participated in September 1942. Former flight navigator B.A. Gubin recalled:

“The regiment commander, Major Mikhail Khvostikov, who flew in tandem with Sergeant Liliya Litvyak, together with other fighters attacked a formation of bombers heading to bomb the Stalingrad Tractor Plant. The major's plane was hit and went sideways. Liliya Litvyak, continuing the attack, approached the bomber and shot down the plane from 30 meters. Then, together with pilot Belyaeva, they entered into battle with approaching enemy fighters. Belyaeva and Litvyak went into the tail of one enemy plane, fired at it and set it on fire.”

Veterans recalled such a story. One day, Lilia Litvyak was called by the regiment commander. She saw a captured German pilot in the room. On his chest were three Iron Crosses. When the regiment commander, through an interpreter, told the prisoner that his plane was shot down by a female pilot, he refused to believe it.

Liliya Litvyak used her hands to depict the turns in the sky that she made to hit his car. The German pilot lowered his head. He was forced to admit that this was exactly how it happened.

On March 22, 1943, Liliya Litvyak was wounded in an air battle. With difficulty, the pilot brought the plane, riddled with shrapnel, to the airfield: pain pierced her leg. Litvyak was sent to the hospital. After treatment, she was given leave for a month. She met her mother and brother. But a week later she left for the front and took to the skies again.

Subsequently, Hero of the Soviet Union B.N. Eremin will write about her: “Lily Litvyak was a born pilot. She was brave and decisive, resourceful and careful. She knew how to see the air."

At the same time, Ekaterina Budanova opened the account of downed planes. An entry appeared in her notebook: “October 6, 1942. A group of 8 aircraft was attacked. 1 set fire, fell to the right of Vladimirovka.”

On that day, German bombers appeared near the only one remaining on the left bank of the Volga railway, through which troops and ammunition were delivered to Stalingrad. Throwing themselves from a height, the Yaks disrupted the formation of German planes. Some were shot down, others threw bombs into the steppe without reaching the target.

October 7, 1942 - another victory: Ekaterina Budanova, together with Raisa Belyaeva, attacked a group of German bombers and shot down one of them.

In those days, Ekaterina Budanova wrote to her sister from the front:

“Olechka, my dear! Now my whole life is devoted to the fight against the hated enemy. I want to tell you that I’m not afraid of death, but I don’t want it, and if I have to die, I simply won’t give up my life. My winged Yak is a good car and we will only die with it as heroes. Be healthy, dear. Kiss. Kate".

Mortal risk and exhausting fatigue, the stress of battle and the natural desire to survive - such were everyday life at the front, which Katya Budanova, like other pilots, accepted with silent patience.

Former squadron commander I. Domnin recalled:

“I often had to fly with Katya in a group. She was painfully worried if she had to remain on duty on the ground. I wanted to fight. When I flew out with her, I was sure that she would reliably cover me and would not lag behind during any maneuver in a difficult situation. Twice on combat missions she saved my life.”

Her front-line biography is captured in short lines of combat reports, which describe battles and count of downed aircraft: “In November 1942, Budanova, as part of a group, destroyed two Messerschmitt-109s and personally shot down a Junkers-88.” On January 8, Budanova, together with regiment commander Baranov, fought with four Fokkers. One of the enemy planes was shot down. From a nearby explosion, the Yak-1, which Budanova was flying, was thrown into the air... In an air battle, Lavrinenkov’s plane was riddled with shrapnel. Budanova covered his plane until it returned to the airfield.”

Maria Kuznetsova said: “When I remember Katya, it’s as if I hear her voice. She loved a song that had these words:

Propeller, sing the song louder,

Carrying spread wings.

For eternal peace, for the last battle

A steel squadron is flying!

Ekaterina Budanova was assigned to a group of ace pilots who flew out on a “free hunt.” Her handwriting in the sky was called “Chkalovsky”, so risky and confident were the aerobatic maneuvers she performed in the air, achieving victory.

The planes on which female fighter pilots fought were serviced by female “technicians.” They also flew in from Engels, where they underwent training.

“The life of the pilot depended on our work,” said Inna Passportnikova-Pleshitseva. – We prepared the planes mainly at night. Everything is done by hand. There were no facilities at the front airfield. We worked in any weather - in the rain, piercing wind. After all, you won’t wait for the puddle under the plane to dry up. In winter, my fingers stuck to the cold metal. We were given warm gloves. But we didn’t put them on - our hands lost dexterity, the work went slower. Once, during a muddy season, she even froze to the ground. But we did not lose heart - we encouraged each other.”

After combat flights, the pilot’s soul required release. “It seems impossible to believe it, but we knew how to enjoy life, even in such an alarming environment,” said Maria Kuznetsova. – Youth took its toll. The pilots often gathered to sing their favorite songs, started the gramophone, and the sounds of foxtrots and tangos rushed across the steppe, pitted with craters, and the then fashionable “Champagne Splashes” and “Rio Rita” sounded. Someone took a button accordion and danced the “gypsy girl”. But there was always a heaviness in my heart: someone won’t return from the flight tomorrow? For someone, this evening will be the last in their lives?

And, despite the constant risk that combat flights were associated with, the young wanted to love and be loved. Liliya Litvyak wrote about her experiences in a letter to her mother and brother:

“What awaits in the new year? There are so many interesting things ahead, so many surprises and accidents. Or something very big, great, or everything could collapse..."

Her premonitions did not deceive her. I was expecting Lilia Litvyak great love which will turn into tragedy. In combat reports, two names began to appear side by side: Liliya Litvyak and Alexey Solomatin. They often flew out as a pair. Alexey gave the command in the air: “Cover! I'm attacking!" When the pilots landed, Alexey, picking a bunch of steppe flowers, ran to the Litvyak plane: “Lilya! You are a miracle!

Alexey Solomatin fought since 1941. He was one of the best pilots in the skies of Stalingrad. In the flying community, his name was associated with a living legend. At Stalingrad, seven pilots under the command of Captain Boris Eremin attacked a group of twenty-five German bombers, which were covered by fighters. In this unequal battle, our pilots emerged victorious without losing a single aircraft! Some enemy vehicles were shot down, others were scattered. The details of this battle, in which Alexey Solomatin also participated, were studied in the aviation regiments in those days.

“Both of them, Alexey and Lilya, were amazingly beautiful,” recalled I. Passportnikova-Pleshivtseva. – When they walked side by side, people smiled, looking at them. There was such tenderness in their eyes. They didn’t hide the fact that they loved each other.”

However, according to the veterans, there were vigilant commanders who decided to separate them - to separate them into different regiments. Someone thought that a love relationship could interfere in battle. Having learned about the upcoming separation, Lilya and Alexey went to the commander of the aviation unit. They say Lilya burst into tears, convincing her to leave them together. And this order was canceled.

But instead of tender dates, the menacing sky of war awaited them, where life could be cut short at any second. They fought with concern for each other.

This happened in May 1943, when after the victory in Stalingrad the battles for the liberation of Donbass began. A decree was then published in the newspapers conferring the title of Hero of the Soviet Union on Alexei Solomatin: he had 17 downed German planes to his credit. The regiment congratulated the brave pilot on high reward. By that time, Alexey and Lilya had become husband and wife. But they were given short-lived happiness. On May 21, Alexey Solomatin crashed in front of Lily.

“That day, together with Liliya Litvyak, we were at the airfield,” recalled Inna Pasportnikova-Pleshivtseva. -We sat next to each other on the plane of the plane. We watched a training air battle that Alexey Solomatin fought with a young pilot who had recently arrived at the unit. Complex figures were performed above our heads. Suddenly one of the planes entered a steep dive and began to approach the ground with every second. Explosion! Everyone rushed to the crash site. Lilya and I immediately got into the semi, which was rushing in that direction. They were sure that a young pilot had crashed. But it turned out that Alexey Solomatin died. It’s hard to convey how desperate Lilya was... The command offered her leave, but she refused. “I will fight!” - Lilya repeated... After the death of Alexei, she began to fly out on combat missions with even greater bitterness.”

Lilia experienced another shock. On July 19, 1943, her close friend Katya Budanova died. Covering a group of bombers, she entered into battle with the German Messerschmitts. She shot down one of the enemy planes, but her plane was also hit by machine gun fire. She was seriously injured. Her Yak-1 landed in a field near the village of Novo-Krasnovka. Having run across the ground riddled with craters, the plane turned over. In the overalls of the deceased pilot, the peasants found blood-stained documents and handed them over to the command.

Their journey from romance to terrible reality was short. One after another, female fighter pilots from the “first draft” group, who flew to fight in the skies of Stalingrad, died.

Raisa Belyaeva was mortally wounded on July 19, 1943 in an air battle over Voronezh. Antonina Lebedeva, who fought on Kursk Bulge, died on July 17, 1943 (her remains were found by Oryol trackers only in 1982). The fate of the pilot Klavdia Blinova turned out to be dramatic: she was shot down over enemy territory. The pilot landed by parachute and was captured. Together with other prisoners of war, she managed to jump out of the railway carriage while moving. She wandered in the forests for two weeks before crossing the front line. I got to my aviation unit.

On August 1, 1943, Liliya Litvyak did not return from the battle. This happened near the city of Anthracite, Lugansk region. Hero of the Soviet Union I.I. Borisenko recalled:

“We took off with eight Yak-1s. Over enemy territory we saw a group of bombers heading towards the front line. They attacked them on the move. But during the battle, the Messerschmitts rushed towards a pair of our fighters. The battle was behind the clouds. One of the Jacobs, smoking, went to the ground. Having landed at the airfield, we learned that Litvyak had not returned from the mission. Everyone felt this loss especially hard. She was a wonderful person and pilot! After the liberation of this area, we tried to find the place of her death, but we never found it.”

Pilot Liliya Litvyak was considered missing for a long time. Years passed until in the city of Krasny Luch, Lugansk region, teacher V.I. Vashchenko, together with the schoolchildren, did not collect materials about the soldiers who liberated these places, including the dead pilots. In the village of Kozhevnya, residents led the rangers to a deep beam and told the following story. Here, in early August 1943, a Soviet plane crashed. The deceased pilot was first buried on the slope of the beam. And when his remains began to be transferred to a mass grave in a neighboring village, an entry appeared in one of the protocols: the downed plane was obviously flown by a woman. This was evidenced by the remains of the pilot, as well as half-decayed items of the women's toilet. Teacher V.I. Vashchenko picked up the documents. I found veterans. I.V. came to the pathfinders. Pasportnikova-Pleshivtseva. Based on the burnt fragments of aircraft parts that the trackers found during excavations, she determined that the Yak-1 fell here. There was no other female pilot killed in the area in early August 1943. A special commission made a conclusion: Lilia Litvyak is buried here.

In the city of Krasny Luch, a monument to the brave pilot was erected in front of the building of school No. 1.

Liliya Litvyak flew 168 combat missions. She was wounded three times. Based on the number of victories she has won, she is called the most successful among female pilots who fought in fighter aircraft.

Liliya Litvyak shot down 12 German aircraft and 4 in the group. In 1990, she was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously.

Ekaterina Budanova has 266 combat missions. She shot down 11 German aircraft. In 1993, she was awarded the title of Hero of Russia.

However, in our time, articles have appeared that name other, more modest results of aerial victories won by fighter pilots. However, no errors in such calculations detract from the feat of these brave girls.

Decades after the Victory, we need not only war statistics. Descendants were left with pages of history that captured the features of the moral world of the front-line generation. And this is the real spiritual Universe, largely unknown due to the passage of years.

During the war, French pilots of the Normandie-Niemen regiment, seeing female pilots at the front, wrote:

“If it were possible to collect flowers from all over the world and lay them at your feet, then even with this we would not be able to express our admiration for the Soviet pilots.”

In the photo (from left to right): Liliya Litvyak, Ekaterina Budanova, Maria Kuznetsova

Special for the Centenary

Svyatoslav Knyazev

On August 1, 1943, the legendary Soviet pilot Lydia Litvyak made her last combat flight. She is called the most successful female pilot of the Great Patriotic War. In just one year of participation in air combat, she carried out 186 sorties, scoring 12 personal victories and four as part of a group. Litvyak, known as the White Lily of Stalingrad, was considered missing for a long time. The exact place of her death was established only several decades later, and the title of Hero of the Soviet Union was posthumously awarded to the pilot only in 1990. ABOUT battle path White Lily of Stalingrad - in the RT material.

- Soviet pilot Lydia Litvyak with her fighter

- RIA News

Born to fly

Lydia Litvyak was destined to connect her life with the sky literally from birth. She was born in Moscow on August 18, 1921 - on All-Union Aviation Day. The girl dreamed about airplanes since childhood. At the age of 14, she signed up for a flying club and a year later she independently flew a winged car into the sky for the first time. She continued her education at the Kherson Aviation School of the USSR Osoaviakhim, after which she was sent to work at the Kalinin Aeroclub. There she managed to personally train 45 cadets. But Lydia began to strive for the front. To get into the ranks of military pilots, the girl even resorted to a trick, crediting herself with flying hours.

- U-2 aircraft of the Kalinin Aeroclub. Summer 1935 © Wikimedia Commons

In 1942, Lydia Litvyak was enlisted in the 586th Fighter Air Defense Regiment. She, like some other pilots who did not have a diploma from a military school, initially served with the rank of sergeant. Having mastered the Yak-1 fighter, Lydia was engaged in air patrol in the Saratov area and escorting transport aircraft. But in early August, she went to the front and opened her personal combat account at Stalingrad, shooting down a Ju 88 bomber. On September 13, during her second combat mission, Litvyak personally shot down another bomber, and working in tandem, an Me-109 fighter. In September, Lydia was transferred to the 437th Fighter Aviation Regiment.

- Yak-1 © Wikimedia Commons

“The Yak-1 was far from the most successful car. And the fact that Lydia Litvyak immediately began to fight very effectively on it testified to a rare combination of skill and luck,” historian and writer Dmitry Khazanov said in an interview with RT.

White Lily of Stalingrad

Lydia asked to draw a white lily on the fuselage of her plane. Soon she received the nickname White Lily of Stalingrad and the call sign Liliya-44. Having won a number of aerial victories, Lydia Litvyak was for some time transferred to the operational subordination of the 9th Guards Fighter Regiment.

“It was luck and recognition of merit. The best fighter pilots served in the 9th Regiment, some of them became Heroes of the Soviet Union twice. You could learn a lot there,” Khazanov said.

According to Lydia’s biographers, the pilot of one of the fighters she shot down managed to evacuate by parachute and was captured by Soviet troops. He turned out to be a German baron, who had previously, according to him, won about 30 aerial victories. He could not believe that he had been shot down by a girl, and was shocked when White Lily showed him with gestures some details of the battle known only to pilots.

At the end of 1942, Lydia Litvyak was transferred to serve in the 296th Fighter Aviation Regiment. On February 11, 1943, she again shot down two planes during one flight: personally, a Ju 88, and as part of a group, an FW 190 fighter. Once during the battle, Litvyak’s plane was shot down and landed on enemy-occupied territory. But her colleagues helped her return to her own people. On February 23, 1943, Sergeant Lydia Litvyak was awarded the Order of the Red Star.

On March 22, near Rostov-on-Don, White Lily shot down a German bomber, and then, covering her comrades, entered into battle with six enemy fighters at once.

“Her car stayed in the air for literally honestly and on one wing. Litvyak herself was wounded in the leg, but still managed to bring the plane to the airfield,” noted the scientific secretary of the Victory Museum, candidate, in an interview with RT historical sciences Sergey Belov.

In 1943, White Lily was awarded the rank of junior lieutenant.

Victories and losses

Lydia Litvyak won several victories at once in May 1943. In addition to enemy fighters, she was able to destroy a balloon - an artillery spotter, which other aircraft could not approach due to the dense fire of air defense systems. White Lily flew up to him from the rear against the sun and shot him down.

However, that same month, Lydia suffered a personal tragedy. Shortly before this, she married her peer - the squadron commander of the 296th regiment, Alexei Solomatin, for whom she was a wingman. On May 1, he was awarded the star of the Hero of the Soviet Union, and on the 21st he died in a plane crash right in front of his wife and colleagues.

- Alexey Solomatin © Wikimedia Commons

“Having lost her loved one, Lydia did not give up, but began to fight even more fiercely,” Khazanov noted.

In July 1943, she won a number of new victories and, even after being wounded, did not want to go to the hospital. However, on July 19, a new loss awaited her. In a battle over Donbass, Litvyak was shot down along with her close friend Ekaterina Budanova. Lydia managed to jump out with a parachute, and Catherine was able to land the plane, but died on the ground from her wounds. In terms of the number of aerial victories, Budanova was second only to White Lily herself.

- Pilots of the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment Lydia Litvyak, Ekaterina Budanova, Maria Kuznetsova

- RIA News

According to the recollections of fellow soldiers, after this incident, Lydia increasingly began to say that she had a feeling of approaching death.

On August 1, 1943, during the battles in the Mius River area, Litvyak made four combat missions and shot down two enemy aircraft personally, and one as part of a group. During the last flight, her plane was hit and crashed, but her colleagues were unable to examine in detail what happened to it due to heavy clouds.

"The Big Exception"

Lydia Litvyak was nominated for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, but did not receive it immediately. At one time, information circulated in the press that this allegedly happened because Lydia was accused of surrendering to the enemy. However, such arguments are questionable, historians note, since in September 1943, junior lieutenant Lydia Litvyak was awarded the Order of the Great Patriotic War, 1st degree, with the annotation “posthumously” and promoted to the rank of lieutenant, although she was officially considered missing.

Also on topic

“I’ll die, but I won’t be a scoundrel”: for what feats was underground fighter Ivan Kabushkin awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union

“I’ll die, but I won’t be a scoundrel”: for what feats was underground fighter Ivan Kabushkin awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet UnionOn July 4, 1943, in a Minsk prison, the Nazis shot the legendary Soviet underground fighter Ivan Kabushkin, nicknamed Jean. He personally...

It took decades to finally establish the fate of the White Lily of Stalingrad. As it turned out later, her remains were discovered only in 1969 near the Kozhevnya farm, but her identity could not be determined then. Lydia was buried in a mass grave as an “unknown pilot.” And only in the 1970s did young search engines from the city of Krasny Luch identify him deceased Lydia Litvyak.

After completing all the necessary procedures in 1988, the name of the pilot was immortalized at the burial site, and in the order of the Main Personnel Directorate of the People's Commissariat of Defense of 1943, the USSR Ministry of Defense made changes indicating that Lydia Litvyak did not go missing, but died while performing a combat mission. tasks. On May 5, 1990, she was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and the rank of senior lieutenant.

“According to the tradition that developed back in the First World War, an ace is considered to be a pilot who shot down more than five enemy aircraft. Lydia Litvyak had 12 personal victories and four more in the group. In ten months, she flew 186 combat missions and fought 69 battles. Her skill was so appreciated that she was included in special group“free hunters” - expert pilots whom the command trusted to independently search for and destroy enemy aircraft. In one of the orders about her award, the author of the document, without mincing words, wrote: “There are no impossible tasks for her,” said Sergei Belov.

- Hitler's plane shot down in battle over Stalingrad

- RIA News

According to Dmitry Khazanov, fighter units formed from female pilots were only in the Red Army during the Second World War. At the same time, the girls withstood such overloads that sometimes even men could not endure.

“Lydia Litvyak was a brave pilot, excellent at shooting in the air, which is given to very few,” the expert emphasized.

According to the seven-time absolute world champion in aviation sports, first class instructor pilot Svetlana Kapanina, it is still much more difficult for a woman to fly an airplane than for a man, not to mention the period of the Great Patriotic War.

“Flying a plane is very physically difficult for a girl. Therefore, in the sky this is not the rule, but a big exception,” the specialist concluded.