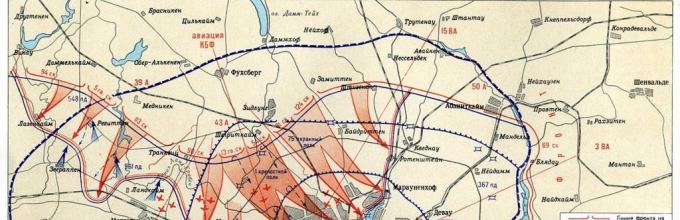

Königsberg operation (April 6-9, 1945) - strategic military operation armed forces of the USSR against German troops during the Great Patriotic War with the aim of eliminating the Königsberg enemy group and capturing the fortified city of Königsberg, part of the East Prussian operation of 1945.

The history of Koenigsberg is the history of the creation of a first-class fortress. The city's defense consisted of three lines encircling Koenigsberg.

The first zone was based on 15 forts 7-8 kilometers from the city limits.

The second defensive line ran along the outskirts of the city. It consisted of groups of buildings prepared for defense, reinforced concrete firing points, barricades, hundreds of kilometers of trenches, minefields and wire fences.

The third zone consisted of forts, ravelins, reinforced concrete structures, stone buildings with loopholes, and occupied most of the city and its center.

The main task facing the command of the 3rd Belorussian Front was to take the city, reducing the number of casualties to the limit. Therefore, Marshal Vasilevsky paid great attention to reconnaissance. Aviation continuously bombed enemy fortifications.

Day and night, careful preparations were made for the assault on the city and fortress of Koenigsberg. Assault groups ranging in strength from a company to an infantry battalion were formed. The group was assigned an engineer platoon, two or three guns, two or three tanks, flamethrowers and mortars. The artillerymen had to move along with the infantrymen, clearing the way for them to advance. Subsequently, the assault confirmed the effectiveness of such small but mobile groups.

STORM TROOPS

What were the new methods of fighting, what were the main features of the use of various types of troops in street battles?

Infantry

THE EXPERIENCE of the assault on Konigsberg shows that the main place in infantry battle formations should be occupied by assault detachments. They penetrate the enemy's battle formations relatively more easily, dismember them, disorganize the defense and pave the way for the main forces.

The composition of the assault detachment depended on the nature of the buildings and the nature of the enemy’s defense in the city. As experience has shown, it is advisable to create these detachments as part of one rifle company (50-60 people), reinforced with one or two 45 mm anti-tank guns mod. 1942, two 76 mm regimental artillery guns mod. 1927 or 1943, one or two 76 mm divisional guns ZIS-3 mod. 1942, one 122 mm howitzer M-30 mod. 1938, one or two tanks (or self-propelled artillery units), a platoon of heavy machine guns, a platoon of 82 mm battalion mortars mod. 1937, a squad (platoon) of sappers and a squad (platoon) of flamethrowers.

According to the nature of the tasks performed, the assault troops were divided into groups:

a) attacking (one - two) - consisting of 20-26 riflemen, machine gunners, light machine gunners, flamethrowers and a squad of sappers;

b) reinforcements - consisting of 8-10 riflemen, a platoon of heavy machine guns, 1-2 artillery pieces and a squad of sappers;

c) fire - as part of artillery units, a platoon of 82 mm mortars, tanks and self-propelled guns;

d) reserve - consisting of 10-15 riflemen, several heavy machine guns and 1-2 artillery pieces.

Thus, the assault detachment seemed to consist of two parts: one, actively operating in front (attack groups), having light small arms (machine guns, flamethrowers, grenades, rifles), and the second, supporting the actions of the first, having heavy weapons (machine guns, guns, mortars, etc.).

The attacking group (groups), depending on the target of the attack, could be divided into subgroups, each consisting of 4-6 people.

Preparing for the battle for the city

FEATURES of the use of various types of troops in battles for the city also determined the variety of forms of combat training for troops. At the same time, special attention was paid to the training of assault troops. During these sessions personnel learned to throw grenades at windows, up and down; use an entrenching tool; crawl and quickly run from cover to cover; overcome obstacles; jump over ditches and fences; quickly climb into the windows of houses; conduct hand-to-hand combat in fortified buildings; apply explosives; block and destroy firing points; storm fortified neighborhoods and houses from the street and by walking through courtyards and vegetable gardens; move through gaps in walls; quickly transform a captured house or block into a powerful stronghold; use improvised means of crossing water barriers in the city.

In this case, the main emphasis was on working out issues of interaction between groups of the assault detachment and within groups.

Tactical training of assault units was carried out on specially equipped training fields. These fields, depending on the conditions, usually had a defensive line consisting of 1-2 lines of trenches; wire fences and minefields; a settlement with strong stone buildings and 2-3 strong points for practicing combat techniques in the depths.

The units learned to attack to a depth of 3-4 km with access to the opposite outskirts settlement and fixing it on it. After the classes, a debriefing was held, during which the groups were practically shown how to perform this or that technique or maneuver.

The training of assault troops was carried out on the basis of specially developed instructions for storming the city and fortress of Koenigsberg and for crossing the river. Pregel within the city.

THROUGH THE EYES OF A SOLDIER

On the night of April 5-6, we conducted reconnaissance in force. We met strong resistance, and there were, of course, losses. The weather was also lousy: there was a light, cold drizzle. The Germans retreated and occupied the first line of defense, where they had a bunker. Our people approached it at 4 o'clock, at dawn, planted explosives and blew up the wall. We smoked out 20 people from there. And at 9 am artillery preparation began. The guns started talking and we huddled to the ground.

I.Medvedev

On April 6, we approached Konigsberg from the south, where Baltraion is now. We hunted for “cuckoos” - individual soldiers or groups of soldiers with radio stations that transmitted information about the movement and concentration of our troops. I caught such “cuckoos” twice: they were groups of three people. They hid in fields, in basements on farmsteads, in pits. And Il-2 planes constantly flew over our heads; the Germans called them “Black Death.” I only saw such a number of planes when we took Vilnius!

N.Batsev

Kaliningrad veterans remember the assault on Koenigsberg. Komsomolskaya Pravda, April 9, 2009

THROUGH THE EYES OF THE REGIMENTAL COMMANDER

At exactly five o'clock a powerful salvo of guns rang out, followed by a second, third, and Katyusha rockets. Everything was confused and drowned in an unimaginable roar.

The artillery fired continuously for about an hour and a half. During this time, it was finally dawn, and the outlines of the fort could be seen. Two shells, one after the other, hit the main gate. They swayed and collapsed.

Shoot! - I shouted to Shchukin.

The adjutant fired a rocket launcher. A moment, another - and the soldiers got out of the trench. “Hurrah” rang out across the entire field in front of the fort.

The assault group was the first to burst into the collapsed gate and strike with bayonets. The third and sixth companies overcame the ditch. And soon we saw a wide white banner slowly, reluctantly creeping up the flagpole of Fort King Frederick III.

Hurray! - officers and soldiers shouted.

Telephone operators and radio operators were in a hurry to convey the order:

The enemy has surrendered. Stop the fire.

The shooting stopped. We got out of the trench. One of the radio operators shouted:

Captain Kudlenok reports: the Nazis are leaving the casemates without weapons, they are surrendering!

THROUGH THE EYES OF A MARSHAL

On April 8, trying to avoid pointless casualties, I, as the front commander, turned to the German generals, officers and soldiers of the Koenigsberg group of forces with a proposal to lay down their arms. However, the Nazis decided to resist. On the morning of April 9, fighting flared up with new strength. 5,000 of our guns and mortars, 1,500 aircraft dealt a crushing blow to the fortress. The Nazis began to surrender in entire units. By the end of the fourth day of continuous fighting, Koenigsberg fell:

During interrogation at front headquarters, the commandant of Koenigsberg, General Lasch, said:

“The soldiers and officers of the fortress held out steadfastly in the first two days, but the Russians outnumbered us and gained the upper hand. They managed to secretly concentrate such a quantity of artillery and aircraft, the massive use of which destroyed the fortifications of the fortress and demoralized the soldiers and officers. We have completely lost control of the troops. Coming out of the fortification onto the street to contact the unit headquarters, we did not know where to go, completely losing our bearings, the city, so destroyed and burning, changed its appearance. It was impossible to imagine that such a fortress as Koenigsberg would fall so quickly. Russian command developed and carried out this operation well. At Koenigsberg we lost the entire 100,000-strong army. The loss of Koenigsberg is the loss of the largest fortress and German stronghold in the East.”

Hitler could not come to terms with the loss of the city, which he declared to be the best German fortress in the entire history of Germany and “an absolutely impregnable bastion of the German spirit,” and in impotent rage he sentenced Lasch in absentia to death penalty.

In the city and suburbs Soviet troops About 92 thousand prisoners were captured (including 1,800 officers and generals), over 3.5 thousand guns and mortars, about 130 aircraft and 90 tanks, many cars, tractors and tractors, a large number of different warehouses with all kinds of property.

While the trophies were being counted, a joyful report flew to Moscow. And on the night of April 10, 1945, the capital saluted the valor, bravery and skill of the heroes of the assault on Koenigsberg with 24 artillery salvoes from 324 guns.

"FOR THE CAPTURE OF KONIGSBERG"

After the end of the war, awards were established for liberation by the Red Army major cities Europe. In accordance with the assignment, medals were developed: for the liberation of Prague, Belgrade, Warsaw, the capture of Berlin, Budapest, Vienna. The medal for the capture of Koenigsberg stands out among them, since it was not a medal for the capture of the capital, but for the capture of a fortress city.

The medal “For the Capture of Koenigsberg” was established on June 9, 1945 by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. The awarding of the medal took place after the end of the war; in total, approximately 760,000 people were awarded the medal “For the Capture of Koenigsberg”

Assault on Königsberg

The world was entering 1945. The outcome of the Second World War was predetermined. But fascist Germany resisted. She resisted with the despair of the doomed. Warsaw had already been liberated, Soviet troops were moving uncontrollably to the west. Berlin lay ahead. His assault became a reality. And it is not at all by chance that some of our military leaders had a plan - to gather forces into one fist and fall with all their might on the capital of Nazi Germany.

But far-sighted strategists and, first of all, Marshal Soviet Union G.K. Zhukov did not forget about the right and left flanks of the Berlin direction, where a significant number of enemy troops were located. Their actions could be the most unexpected. After the war, such fears were confirmed. The German command really had the intention - in the event of the formation of a “Berlin bulge”, to cut its base with a two-sided simultaneous flank attack. Thus, on the territory of East Prussia, the Zemland Peninsula and adjacent territories there was an army group with a total of about forty divisions. Leaving them in your rear was extremely dangerous.

That is why the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command decided to use the forces of the 2nd and 3rd Belorussian Fronts, commanded by talented commanders Marshal of the Soviet Union K.K. Rokossovsky and Army General I.D. Chernyakhovsky. With the help of the troops of the 1st Baltic Front, led by Army General I.Kh. Bagramyan, cut off these troops from the main German forces, dismember them, press them to the sea and destroy them.

The main attack on Koenigsberg, which had been turned into a military fortress, was entrusted to the 3rd Belorussian Front. And the 2nd Belorussian Front was supposed to operate west of Koenigsberg and defeat the German troops located there. Both fronts had large forces. One and a half million soldiers, twenty thousand guns and mortars, three thousand tanks and self-propelled artillery units were ready to strike. Two air armies, the 1st and 3rd, supported the ground forces. They had three thousand aircraft. Thus, in the East Prussian direction and in northern Poland, our troops outnumbered the enemy in manpower by 2.8 times, in artillery by 3.4 times, in tanks by 4.7 times, and in aircraft by 5.8 times.

Nevertheless, a very difficult problem had to be solved. In front of the Soviet troops lay Germany, whose territory had been turned into a continuous defensive zone. Countless pillboxes, bunkers, trenches, anti-tank ditches and gouges, and other engineering structures, made with German care, seemed capable of stopping any army. Any, but not the Soviet one, hardened in the crucible of an almost four-year battle with the fascist aggressor.

Having reached the German border, the troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front delayed their offensive. Comprehensive and detailed preparations for the East Prussian operation began. The armies were preparing for a breakthrough. Ground and air reconnaissance was carried out around the clock, and artillerymen identified targets to be struck. Maximum effect at minimum quantity victims - this rule has become basic for every officer and general. Unfortunately, it was not immediately adopted and was paid at a very high price.

Looking at the German soil lying in front of them through binoculars, our soldiers experienced a keen feeling. It was from here that at dawn on June 22, 1941, fascist hordes rushed into our country; here was one of the springboards of aggression. And now it has come - this hour of retribution for the many thousands of destroyed cities and villages, for the death of millions and millions of Soviet people.

The morning of January 13, 1945 arrived. Cold, cloudy. When dawn broke, thousands of guns struck along a large stretch of the front. And soon tanks and infantry went on the attack. The assault on the East Prussian stronghold began.

But the main obstacle was not enemy resistance. The wind brought thick fog from the Baltic Sea. He hid the enemy's firing points from observation, the tanks lost their bearings, and aviation and artillery could not provide effective assistance to the advancing infantry. But it was no longer possible to stop or delay the actions of the troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front. For on that day a gigantic strategic offensive unfolded along the entire front from the Baltic to Budapest. And the East Prussian operation was an integral part of it.

Our troops captured only three lines of trenches on the first day; the attackers managed to advance only one and a half kilometers, and even then not everywhere. The Germans threw more and more reserves into battle, including tanks. Our tank units, equipped with new models of heavy armored vehicles, entered the battle with them. In five days of fierce fighting, our troops covered twenty kilometers, but they were never able to enter the operational space. Behind the fortieth line of trenches the forty-first began immediately and so on. The defense lines stretched all the way to Koenigsberg. A day after the start of the offensive, the troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front deployed fighting and the 2nd Belorussian Front, which also met stubborn enemy resistance. But all the efforts of the German troops to restrain the pressure of the Soviet army were in vain. Gumbinnen was taken by storm, and Insterburg fell on January 22. Our troops entered the streets of other German cities. And soon the divisions of the 2nd Belorussian Front reached the shore of Frisches Huff Bay. No, military successes were not easy for us. The number of infantry divisions was reduced to two to three thousand people, which was less than the composition of the pre-war regiment. The tankers who paved the way for the infantry suffered heavy losses. The whole country was grieving the death on February 18 on the battlefield of the commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front, twice Hero of the Soviet Union, Army General I. D. Chernyakhovsky. The people lost one of their most talented and youngest commanders. Marshal of the Soviet Union A.M. Vasilevsky was appointed the new commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front. He had to, commanding the combined forces of the two Belarusian fronts and the joining 1st Baltic Front, complete operations in East Prussia.

The enemy defended himself with ever-increasing tenacity. He managed to delay our units for some time in the Heilsberg fortified area, where the defense was held by a powerful enemy group of several divisions, using nine hundred reinforced concrete houses. On February 19, having replenished the Zemland task force with troops from the Courland group, the enemy simultaneously launched two counter strikes - one from Koenigsberg, the second from the Zemland Peninsula. After three days of fierce fighting, the Nazis managed to somewhat push back our troops and create a corridor connecting the Koenigsberg group with the Zemland group. That's when the need for unified command arose. Headquarters subsequently made a fully justified decision to transfer all Soviet troops operating on the territory of East Prussia to the 3rd Belorussian Front.

And then the day came when our units reached the outer defensive lines of Koenigsberg, located fifteen kilometers from the city outskirts. But it was impossible to storm the city on the move; comprehensive, thorough, deeply thought-out preparation was required. Having surrounded the capital of East Prussia, which had been turned into a seemingly impregnable fortress, our troops stopped. It was necessary to replenish the combat strength of units and formations, accumulate the required amount of ammunition, and most importantly, carry out thorough reconnaissance.

The losses of the Soviet troops were noticeable; we were dealing with a strong and experienced enemy. Its power is evidenced by the fact that in the fierce battles to defeat the Heilsberg group, 93 thousand were killed and more than 46 thousand enemy soldiers and officers were captured in two weeks. 605 tanks, 1,441 guns were captured and destroyed, and 128 aircraft were shot down. But an even more severe test lay ahead.

Final preparations for the assault

They stood opposite each other, fully aware that a decisive battle was close and inevitable. By the beginning of April, the German operational group "Semland", consisting of eleven divisions, one brigade and several infantry regiments and Volkssturm battalions, continued to defend itself in the area of Konigsberg and the Samland Peninsula.

The Koenigsberg garrison directly included five infantry divisions, fortress and security units, numbering over 130 thousand soldiers, up to four thousand guns, more than a hundred tanks and assault guns. Air support was provided by 170 aircraft.

But the Nazis pinned their main hope not on the number of soldiers and guns, but on those fortifications that had been created over centuries, repeatedly rebuilt and modernized. The city's defense consisted of three lines encircling Koenigsberg. The first zone was based on 15 forts 7-8 kilometers from the city limits. The second defensive line ran along the outskirts of the city. The third, consisting of forts, ravelins, new reinforced concrete structures and stone buildings equipped with loopholes, occupied most of the city and its center. The streets were blocked by anti-tank ditches and gaps, barricades, and trenches. Almost all forts had the shape of a pentagon, surrounded by a moat with water; the depth of the moats reached seven meters. The reinforced concrete and earthen coverings of the caponiers withstood the impacts of three-hundred-millimeter gun shells and heavy aerial bombs. The fortress artillery was hidden in the casemates of the forts and was brought to the surface during the battle. The forts had their own power plants installed in the underground floors, large reserves of ammunition and food, which allowed them long time fight in conditions of complete encirclement. The garrisons of the forts numbered from three hundred to five hundred soldiers and officers. If you take into account the tens of thousands of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines laid in the path of the attackers, you can imagine how difficult the task was for the troops storming Koenigsberg to solve.

The main task facing the command of the 3rd Belorussian Front was to take the city, reducing the number of casualties to the limit. As you know, attackers always suffer more losses. Death is always scary. But it was especially bitter at the very end of the war, when the feeling of imminent victory penetrated the soldiers’ hearts. That is why Marshal Vasilevsky paid exceptional attention to intelligence. He understood that it was impossible to storm an unfamiliar city blindfolded, that not all the soldiers and officers of his armies had experience in street fighting, when the windows of almost every building become fire-breathing embrasures. Aviation continuously bombed enemy fortifications. But planes that did not throw bombs also flew over Koenigsberg. They had a different task; these planes took aerial photographs of the city. This is how a detailed map was created, reflecting in every detail the outlines of Koenigsberg, which, under the attacks of Allied aviation, changed its appearance in many ways. The city center especially suffered in the fall of 1944 from carpet bombing by Anglo-American aircraft. So the commanders of divisions, regiments and even battalions received maps of those urban areas where they were to fight.

But that was not all. At the front headquarters, based on aerial photographs, craftsmen created a model of the entire Königsberg with its streets, back streets, fortresses, pillboxes, and individual houses. Day and night near this toy city, commanders of units and formations played far from childish games. There was a search for optimal options for the assault. To attack blindly meant dooming thousands and thousands of soldiers' lives. The maximum reduction in losses measures the talent of a military leader.

To carry out the assault on Koenigsberg, the 43rd Army under the command of General A.P. Beloborodov and the 50th Army under the command of General F.P. Ozerov were brought in, which struck from the north. From the south, the 11th Guards Army of General K.N. Galitsky went to storm the city. The 39th Army was entrusted with the task of preventing German troops located in the area of the cities of Pillau (Baltiysk) and Fischhausen (Primorsk) from coming to the aid of the Königsberg garrison. To influence the enemy from the air, three air armies were allocated, which included about 2,500 aircraft. General management of aviation operations was carried out by the commander of the USSR Air Force, Chief Marshal of Aviation A. A. Novikov.

And yet, the decisive role in the assault on the city was assigned to artillery of all calibers, including ultra-high-power guns, which had not previously found use in the theater of military operations due to their immobility. Artillery was supposed to demoralize the enemy, suppress his resistance, and destroy his long-term defensive structures. By the beginning of the assault, the front had five thousand guns.

Within a month, reserve artillery of the Supreme High Command arrived at the positions. Eight batteries of the 1st Guards Naval Railway Artillery Brigade were delivered along specially laid tracks. Special concrete platforms were built for heavy guns. An extreme density of artillery barrels was created in the directions of the main attacks and breakthrough areas. Thus, in the zone of the upcoming offensive of units of the 43rd Army, 258 guns and mortars were concentrated on a kilometer of front. A large role was given to guards mortars - the famous Katyushas.

Day and night, careful preparations were made for the assault on the city and fortress of Koenigsberg. Assault groups ranging in strength from a company to an infantry battalion were formed. The group was assigned an engineer platoon, two or three guns, two or three tanks, flamethrowers and mortars. Our soldiers successfully used Faust cartridges captured from the enemy in large quantities. The artillerymen had to move along with the infantrymen, clearing the way for them to advance. Subsequently, the assault confirmed the effectiveness of such small but mobile groups.

There was also intense studying going on. Everyone studied: experienced soldiers, platoon and company commanders, generals seasoned in many battles. At one of the meetings, the front commander, Marshal Vasilevsky, said: “The accumulated experience, no matter how great it is, is not enough today. Any mistake, any mistake by the commander is an unjustified death of soldiers.”

The hour for the start of the assault was approaching. The offensive was originally scheduled for April 5. But thick clouds, rainy weather and fog rolling in from the sea forced the assault to be postponed for a day. On March 31, a meeting of the military councils of all armies blockading Koenigsberg was held, where the directive of the front commander to storm the fortress was announced. It defined specific, clear tasks facing the commanders of armies, military branches and other military leaders.

Artillery was the first to enter the battle four days before the assault. On April 2, the barrels of heavy guns began to hum. The walls of the forts and pillboxes shook from the explosions of large-caliber shells. They did not fire blindly, each battery, each gun had its own, already targeted target.

Much attention was paid to the interaction of all types of troops, timely provision of them with ammunition and communications. In all units, political workers had conversations with the soldiers, talking about the city that they had to storm, about the significance of taking this citadel. It was in the units that the text of the oath of the guardsmen was born, under which tens of thousands of soldiers and officers going on the assault put their signatures. They vowed not to spare their lives in this one of the last battles with fascism.

Starting from April 2, three times a day, messages were broadcast through loudspeakers from forward positions and on radio. German transmissions addressed to the troops of the besieged garrison. They provided reports on military operations on the fronts and reported decisions Yalta Conference heads of state of the Allies, a letter from fifty German generals opposing the fascist regime, calling for an end to senseless resistance, was read out. Thousands of leaflets were dropped on the city, and artillerymen sent propaganda shells stuffed with leaflets.

Extremely important and dangerous work was carried out by a detachment of German anti-fascists, led by the commissioner of the Free Germany National Committee, Oberleutnant Hermann Rench. His assistant Lieutenant Peter and his comrades managed to penetrate into Koenigsberg and withdraw from there almost completely one of the companies of the 561st Grenadier Division.

Until the very beginning of the assault, no one knew a minute of rest. Tired to the point of exhaustion, the sappers built ladders, assault bridges and other devices. The soldiers included in the tank landing forces learned to jump onto moving vehicles and dismount at low speeds, and studied signals for interaction in battle with tank crews. Miners got acquainted with new samples of German mines filled with liquid explosives. Everyone learned the art of assault.

In the trenches, in places where troops were concentrated preparing for the assault, sheets with the text of the oath of the guardsmen were passed from hand to hand. Thousands, tens of thousands of signatures of soldiers were placed under the oath of allegiance to the Fatherland, to their people. The soldiers promised not to spare their strength, and if necessary, their lives in this one of the last battles with fascism. They knew that a difficult test awaited them. By the evening of April 5, preparations for the assault were completely completed. The next morning there was a decisive battle ahead.

Dawn came slowly. The night seemed to not want to give up its place to him. This was facilitated by dense clouds hanging over the city and continuous fog. The minutes dragged on agonizingly long.

All night long, quiet explosions were heard from the direction of the city. This was done by the 213th and 314th light night bomber divisions of Major General V.S. Molokov and Colonel P.M. Petrov. What was the little Po-2 car like? Strictly speaking, this is not a combat aircraft, but a training aircraft. Made of wood and fabric, it was completely defenseless against fighters, and it could only carry 200 kilograms of bombs. But when these machines appeared silently in the night sky, with their engines turned off, like bats, then the strength of their combat and psychological impact it was difficult to overestimate the enemy.

And then at nine o’clock in the morning on April 6, 1945, an ever-increasing roar broke the silence from the southern side of the city. It was all the artillery of the 11th that spoke Guards Army General Galitsky. The sky was crossed by the tracks of rockets from Guards mortars. Heavy artillery fell on well-explored and targeted fortifications. At ten o'clock in the morning the guns and mortars of the 43rd, 50th and 39th armies advancing from the north opened fire. Five thousand guns literally broke into enemy defenses. Bad weather and thick smoke from shell explosions that filled the city limited air operations. This smoke screen also interfered with the artillerymen.

Nevertheless, at exactly twelve o'clock in the afternoon, assault groups, supported by tanks and self-propelled guns, rushed to attack enemy positions.

The Guards 31st Rifle Division, part of the 11th Army, resembled a twisted spring. An hour before her attack, all artillery fire was transferred to nearby positions. Fire points in the trenches were suppressed. And when the battalions launched an assault, within thirty minutes the division commander received a report that the first line of trenches had been captured. The artillerymen shifted their fire into the depths of the enemy's defenses.

every major building. The assault groups used anti-tank grenades to knock down the doors of houses, fought for staircases and separate rooms, and fought hand-to-hand with enemy soldiers. It was difficult to distinguish those who accomplished feats and those who did not. From the first minutes of the assault, heroism became widespread. Senior Sergeant Telebaev was the first to go on the attack and was the first to break into the enemy trench. He killed six Nazis with a machine gun and captured three. The sergeant himself was wounded, but refused to leave the battlefield and continued to fight. By thirteen o'clock the division's regiments approached the second line of defense, but met stubborn resistance from the enemy, who brought up reserves. The attack faltered. And then the second echelon regiments were forced to enter the battle. The assault groups carried guns on their hands. They literally bit into the enemy's defenses. Only three hours later our soldiers broke into the second line of enemy defense.

To the left of the 31st Division, the 84th Guards Division acted just as decisively. Going on the attack after artillery preparation, she immediately captured the enemy’s first line of defense. Dozens of soldiers were captured and a large amount of weapons were captured. The relatively weak enemy resistance in the first hours of the assault was explained by the fact that a significant part of the enemy's manpower was destroyed and demoralized by heavy artillery fire. Most of the surviving soldiers retreated to an intermediate line in the area of the suburban village of Spandinen.

Fort No. 8, named after King Frederick the First, stood in the way of the attackers. It was a powerful defensive structure. Built half a century ago, the fort has been modernized and strengthened several times. Thick walls reliably protected the garrison from mounted fire; the territory adjacent to the fort was shot through by fortress guns and machine guns. The entire perimeter of the fort was surrounded by a ditch filled with water, ten meters wide and seven meters deep. The water surface of the ditch with its steep stone banks was shot with dagger fire from machine guns hidden in the embrasures. The commander of the 84th division, General I.K. Shcherbina, set the 243rd regiment the task of capturing the flour mill buildings, completely blocking Fort No. 8 and destroying its garrison.

If the task with the factory was solved successfully, then the assault on the fort required great effort. It was bombed again and again by aircraft and fired upon by heavy guns. But as soon as our battalions approached the fortress, they were met by strong artillery and machine-gun fire. The escort guns, which fired directly, could not inflict noticeable damage on the enemy. And only at eighteen o’clock the soldiers reached the defensive ditch. The soldiers saw the flashes of exploding shells and flares reflected in the black water. It turned out to be impossible to suppress enemy machine-gun fire from caponiers. And yet, by midnight, the fort was not only completely blocked, but the sappers managed to overcome the ditch and place boxes of explosives at the walls of the fort.

This is how the first day of the assault on Konigsberg went from the southern side - that part of the city where the Baltic region of Kaliningrad is located today.

The main blow was delivered to the northern part of Koenigsberg. Just like in other areas, intensive artillery preparation was carried out here four days before the assault. From here, powerful bomb attacks were launched from field airfields on fortified enemy targets. The northern group united troops of the 50th, 43rd and 39th armies.

Today, from the highway going to Svetlogorsk, you can see a two-story house standing on a hillock at a fork in the road. Here was the command post, from where Marshal of the Soviet Union A.M. Vasilevsky, his deputy Army General I.Kh. Bagramyan and other military leaders led the assault on Koenigsberg. On April 6, just before dawn, Vasilevsky and Bagramyan arrived here. The telephones were constantly ringing, the commanders of corps and divisions reported on the readiness of the troops for the assault.

At nine o'clock in the morning the roar of guns was heard from the opposite side of Konigsberg. It was the artillery of the 11th Army that spoke, the southern ones entered the boom. And soon more than a thousand guns of the northern group brought down the full power of their fire on the city. At noon the infantry went into battle. There was immediate success. The riflemen captured the first and then the second line of trenches. Within an hour, the commander of the 54th Corps, General A.S. Ksenofontov, reported that the assault detachment of Captain Tokmakov had reached and surrounded Fort No. 5 Charlottenburg, which was considered one of the most powerful strongholds of the enemy. Today a memorial complex has been built there, and probably few Kaliningrad residents and guests of the city have not visited this place.

Surrounding a heavily fortified fort is not all. Taking it is much more difficult. Then the only correct decision was made. The assault groups left the fort in their rear, and they themselves continued the attack on the urban suburb of Charlottenburg (Lermontovsky village of the Central region). The fort was blocked by units of the 806th regiment of the second line. A unit of sappers was also brought up here, and self-propelled artillery units arrived.

Soon after the start of the assault, a tragedy almost occurred. The main command post was hit by a salvo from an enemy artillery battalion. Army General I. Kh. Bagramyan was slightly wounded, and General A. P. Beloborodov was shell-shocked. A few minutes later, Marshal A.M. Vasilevsky returned from the front line. Instead of condolences, he scolded the generals: there were jeeps parked openly in the yard. It was they who unmasked the command post. Two of the officers at the checkpoint were killed.

By the end of the day, the 235th division of General Lutskevich had completely cleared Charlottenburg. The divisions of General Lopatin's 13th Guards Corps were successfully advancing in the center. The hardest part was on the right flank. Units of the 39th Army, aimed at the Koenigsberg - Fischhausen (Primorsk) corridor, advanced very slowly.

The fifth tank and other divisions of the enemy Zemland group more than once rushed into a counterattack, trying to prevent the complete encirclement of Koenigsberg. During the battle, suffering significant losses, we had to take literally every meter.

Bad weather interfered with air operations on the first day of the assault. The bombers were practically inactive. The attacking units were supported by IL-2 attack aircraft, performing the task of directly escorting the infantry. Air strikes were provided by air controllers. They were in the combat formations of the advancing units, having mobile radio stations at their disposal. The main targets of attack aircraft were enemy firing points, artillery positions, tanks and infantry. Only in the second half of the first day of the assault did the clouds clear up somewhat, which made it possible to take more aircraft into the air. Enemy aircraft did not offer serious resistance. There were only a few air battles, and even then these were random encounters. Nazi pilots simply could not evade them.

As night approached, the fighting in the city weakened. Unfortunately, the tasks assigned to the troops were not fully completed. The advance of the attacking units ranged from two to four kilometers. But the main thing was done: the enemy’s defenses were breached, the enemy suffered great material damage, and communications between his units and command posts were disrupted. What is very important is that the enemy, feeling the full power of the attackers, realized that it was impossible to defend the city, that the encircled garrison was doomed to defeat. Soldiers and officers, including senior ones, began to voluntarily surrender to our troops.

The booms did not subside all night. True, they were sporadic and were not as massive as in the daytime. The enemy used the night hours to build new fortifications, restore broken communications, and bring up reserves to the first lines of defense. Our formations also conducted a night regrouping of troops. The second day of the assault was to be decisive.

Hot battles broke out along the entire line of contact between the troops even before dawn. The enemy took a desperate attempt turn the tide of the battle. The last reserves and hastily assembled Volkssturm detachments were thrown into the counterattack. But all this turned out to be in vain.

If the first day of the assault could be called the day of artillery, then the second truly became the day of aviation. The weather improved and the sun shone through the breaks in the clouds. On April 7, long-range bomber aircraft were used for the first time in daylight conditions. The bombers of the 1st and 3rd Air Armies, carefully covered by fighters over the battlefield, had an unhindered opportunity to bomb enemy positions. Enemy airfields were completely blocked. In just one hour, 516 bombers dropped their deadly cargo on Konigsberg. On April 7, our aviation made 4,700 sorties and dropped more than a thousand tons of bombs on enemy positions. It seemed that dawn would never come that day. For the night twilight was replaced by darkness created by smoke from exploding bombs and shells and burning buildings. The aviation that entered the battle finally determined the outcome of the battle in our favor.

And yet the enemy fiercely resisted. Only in the sector of the 90th Rifle Corps of the 43rd Army advancing from the north, they launched fourteen major counterattacks in one day. One after another, the garrisons of the forts capitulated and stopped resisting. It was already discussed above that our troops, advancing from the south, blocked Fort No. 8 on the first day of the assault. The garrison, hiding behind thick walls, continued to resist. Shooting at loopholes and direct fire from guns did not produce any results. At night, high-explosive flamethrowers were delivered to the fort. To overcome the ditch, the commander of the assault battalion, Major Romanov, chose the section of the fortress that was most easily susceptible to flamethrowers. At dawn on April 7, smoke bombs were dropped into the ditch, and a wave of fire emitted by flamethrowers forced the defenders to take cover in the interior. One of the companies, using prepared assault ladders, quickly descended from the steep wall into the water and entered the gentle opposite bank. Hidden by the smoke, the soldiers quickly climbed to the roof of the fort and rushed into the gaps formed by direct hits from heavy bombs and shells. Hand-to-hand combat began in the dark passages and caponiers of the fortress. The enemy was forced to weaken the outer defenses, which allowed another company to overcome the ditch. Under the cover of machine-gun fire, our soldiers crawled to the embrasures of the lower floor of the fort and began throwing grenades at them. Unable to withstand simultaneous attacks from different sides, the garrison capitulated. The commandant of the fort, several officers and more than a hundred soldiers surrendered. 250 enemy soldiers were destroyed in this battle. The battalion captured ten guns, warehouses with a month's supply of food, ammunition, and fuel for the power plant.

On the second day of the assault, the troops of the 11th Guards Army advancing from the south completely liberated the urban area of Ponart (Baltic region) and reached the banks of the Pregel River, which cuts Koenigsberg into two parts. Drawbridges were blown up water surface The river was shot through at any point, but nevertheless our troops had to overcome this water barrier.

And behind the advancing troops, a hot battle was still in full swing. The Nazis turned the massive building of the main station and a large railway junction into a powerful stronghold. All stone buildings here were prepared for defense. The enemy launched frequent counterattacks from the area of the main railway station. The 95th and 97th regiments went to storm the junction; our tanks and self-propelled guns crawled right along the railway tracks. It was necessary to additionally bring guns and rocket launchers into this battle area. Literally every building had to be stormed. Even passenger trains that did not have time to move away from the platform were turned into firing points. Freight cars were used in a similar way. Nevertheless, by eighteen o'clock the troops of the 31st division had actually captured the station and approached the third line of enemy defense, covering the central part of the city.

But our troops also suffered heavy losses. The 11th Division, the last reserve of the corps, came to the aid of the 31st Division. Fighting continued around the remaining forts. During the assault on the powerful fort “Juditgen”, senior lieutenant A. A. Kosmodemyansky, the brother of the legendary Zoe, distinguished himself. His self-propelled gun smashed the gates of the central entrance and, together with the assault groups of Majors Zenov and Nikolenko, burst into the courtyard of the fort, after which the garrison capitulated. More than three hundred enemy soldiers and officers surrendered here, and twenty-one guns were captured. This time the losses of the attackers were reduced to a minimum. The ultimatums that our troops presented to the garrisons of the forts before the start of the assault became increasingly effective.

But Fort No. 5 Charlottenburg, already located in the rear of our troops, continued to offer stubborn resistance. Even a 280-mm gun, which hit him with direct fire, could not break the tenacity of the besieged. Then guns of smaller calibers began to speak, which opened aimed fire at the embrasures of the fort. So they managed to drive the garrison into the underground floors. Covered by heavy fire, the sapper platoon of Lieutenant I.P. Sidorov, who planted several hundred kilograms of explosives under the walls of the fort, crossed the water ditch with great difficulty and losses. Its explosion created large gaps into which the assault detachment of Senior Lieutenant Babushkin burst. But it was still not possible to complete the capture of the fort right away. It was a deadly fight where no one asked for mercy. In hand-to-hand combat alone, our paratroopers destroyed more than two hundred Nazis, and captured about a hundred soldiers and officers. The battle lasted all night and ended only on the morning of April 8. Fifteen Soviet soldiers were awarded for heroism during the capture of Fort No. 5 highest award- title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

The heroism of Soviet soldiers was massive and unparalleled. The fame of the battalion's young Komsomol organizer, junior lieutenant Andrei Yanalov, had passed even before his death. Not through lectures and conversations, but through personal example, he convinced his comrades in arms. In one of the battles, Yanalov personally destroyed more than twenty Nazis, including two officers. In his last battle, Andrei suppressed the fire of two machine guns with grenades. He was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, and the street where the young officer died bears his name today. Thousands of such examples of heroism can be cited.

The second day of the assault was decisive. In a number of places the third and final line of enemy defense was broken through. 140 blocks and several urban villages were taken in battle that day. The surrender of enemy soldiers and officers became widespread.

The futility of further resistance was understood not only by those in the trenches and pillboxes. At night, at the end of the day, the commander of the Koenigsberg garrison, Infantry General Otto Lyash, contacted Hitler's headquarters and asked for permission to surrender the city to Soviet troops. A categorical order followed - to fight until the last soldier.

And victory was close. The soldiers of the 16th Guards Rifle Division, who broke through from the south to Pregel, had already seen flashes on the opposite bank of the river. The soldiers of the 43rd Army, advancing from the north, fought there. Between the steel pincers there was only central part cities. The hours of the city and fortress of Königsberg were numbered.

The third, and penultimate, day of the assault can most accurately be described in one word - agony.

Even at night, Hitler’s elite made a desperate attempt to escape from the destroyed, burning city and make their way to Pillau, from where individual ships departed for Hamburg. Several heavy Tiger tanks, Ferdinand assault guns, and armored personnel carriers were concentrated in the courtyard of one of the city forts. In addition to the crews, they housed officials of the fascist leadership of East Prussia, who took the most important documents. In the darkness of the night, the gates opened and, with engines roaring, a steel column burst out of the fort. But she too was doomed. The further the tanks moved along the streets, illuminated by the fire of burning buildings, the fewer of them remained. An hour later it was all over.

At night, the guards of the corps of General P.K. Koshevoy crossed Pregel under enemy fire. The first to cross to the northern shore were the assault troops of the 46th Guards Regiment and the mortarmen of Captain Kireev from General Pronin's division. By morning, the entire 16th Guards Rifle Division had already overcome the water barrier. With a swift attack, she captured the carriage building plant. And at 14:30, in the area of the current Pobeda cinema, the division linked up with units of the 43rd Army, advancing from the north. The ring has closed.

In an effort to avoid senseless casualties, Marshal Vasilevsky turned to the surrounded enemy troops with a proposal to lay down their arms. But in response to this, another attempt was made to break the encirclement and escape to Pillau. To support this operation, the Zemland group of Germans carried out a counter attack. But, apart from thousands more killed, it brought nothing to the enemy.

During these hours, when the spring air was literally saturated with the smell of imminent victory, our heroes continued to die. In the center of Konigsberg, the Pregel River was to be crossed by formations of the 8th Guards Rifle Corps. But for this, a bridgehead was needed on the opposite northern bank of the river. A handful of guardsmen managed to cross. Here are their names: Veshkin, Gorobets, Lazarev, Tkachenko, Shayderevsky and Shindrat. Here are their nationalities: Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Jew. A battalion of fascists was thrown against them, but the heroes did not retreat, they accepted their last Stand. When our units broke through to the place of the bloody battle, the heroes had already died. And dozens of Nazis lay nearby. One of the paratroopers had a piece of paper clutched in his fist, on which he managed to write: “Here the guards fought and died for the Motherland, for brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers. They fought, but did not surrender to the enemy. Farewell!" This is how six paratroopers, children of four Soviet nations, died. They all had one great Motherland.

On April 8, Soviet air strikes reached their maximum strength. Combat work the pilots began before dawn and did not stop with the onset of darkness. In the morning, attack aircraft and daylight bombers took to the air. Some of them smashed the enemy in Koenigsberg itself, the other - infantry and tanks of groups located to the west of the city. And three six "silts", led by Major Korovin, covered the crossing of units of the 16th division to the northern bank of the Pregel.

The command of the fortress garrison had one hope left - outside help to withdraw the remnants of the troops from Koenigsberg. The commander of the 4th German Army, General F. Müller, again began to pull up forces west of Koenigsberg to deliver a relief strike. Aviation was tasked with thwarting this enemy plan. The main forces of the 3rd and 18th Air Armies were brought in to operate against German troops concentrated west of the city. Bomber strikes alternated with strikes by “silts” and fighters performing the functions of attack aircraft. All day west of Koenigsberg there was an incessant roar from bomb explosions. On April 8, almost three thousand sorties were flown against the enemy's relief force and more than 1,000 tons of bombs were dropped. Unable to withstand such a blow, the group began to retreat to Pillau. April 8 Soviet pilots destroyed 51 aircraft, essentially completely depriving the garrison of aviation.

By the end of the third day of the assault, our troops occupied over three hundred city blocks. The enemy still had a more than illusory hope of holding out for some time in the center of the city, where the ruins of the Royal Castle, destroyed by Anglo-American air raids in the fall, towered. Lyash’s underground command post was located two hundred meters from the castle.

The operational report of the Supreme High Command for April 8 states that during a day of fierce fighting, troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front, advancing on Koenigsberg from the north-west, broke through the outer perimeter of the fortress positions and occupied the urban areas: Juditten, Lavsken, Ratshof, Amalienau , Palfe. Front troops advancing on the city from the south occupied the urban areas: Schönflies, Speichersdorf, Ponart, Nasser Garten, Kontinen, the main station, Konigsberg port, having crossed the Pregel River, occupied the urban area of Kosee, where they joined forces with the troops advancing on Konigsberg from the north. west.

Thus, the front troops completed the encirclement of a significant group of enemy troops defending the city and fortress of Koenigsberg.

During the day of the battle, the front troops captured over 15,000 German soldiers and officers.

The last night of the besieged fortress was approaching. It was not tactical plans, but rather the despair of the Nazis that dictated attempts to regroup their troops and create new firing positions.

Later, in his memoirs, General Lyash will tell you that headquarters officers often could not find the necessary units to convey the commandant’s orders, because the city had become unrecognizable.

Darkness never came that evening. The streets were illuminated by the fire of burning buildings. The sky glowed from the glow of the burning city. General Lyash admitted that the penultimate day of the assault was the most difficult and tragic for the encircled group. Soldiers and officers increasingly realized the complete pointlessness of further resistance. But the more desperate was the resistance of the Nazis, fanatically loyal to Hitler. They doomed not only themselves, not only their soldiers, but also civilians who had taken refuge in the basements of houses to senseless death.

And now it has come - the last day of the assault on Koenigsberg. The enemy did not capitulate, and every minute continued to claim the lives of our soldiers. It was impossible to delay completing the operation. In the morning, as in the first hours of the assault, all five thousand guns began to speak. At the same time, 1,500 planes began to bomb the fortress. After such a powerful blow, the infantry moved forward again.

Actually, the Nazis no longer had a single, coherent defense. There were numerous pockets of resistance, in the center of the city alone there were over forty thousand soldiers and officers, and a lot of military equipment. Nevertheless, the Germans began to surrender in entire units. Soldiers came out of basements and destroyed houses with white rags in their hands. Many faces bore the stamp of some kind of detachment, indifference to what was happening around, to their own fate. These were morally broken people, not yet able to fully comprehend what had happened. But there were also many fanatics. History has preserved such an episode. A large column of surrendered German soldiers slowly moved along the street. She was accompanied by only two of our machine gunners. Suddenly, a German machine gun hit the prisoners from the window of the house. And then, having given the command to lie down, two soviet soldier entered the battle, defending their recent enemies who had laid down their arms. The machine gunner was destroyed, but our elderly soldier, who had walked the roads of war for four years, did not rise from the ground. German soldiers carried his body in their arms.

The encirclement ring was compressed towards the center and was shot right through by gun and mortar fire. Morale among the troops, especially in the Volkssturm battalions, fell more and more. However, the SS and police regiments continued desperate resistance, hoping for help from the German 4th Army.

At 2 p.m., the commandant of the fortress, Infantry General Otto Lyash, convened a meeting. There was only one question discussed - what to do next? Some commanders of the formations, including Lyash himself, considered further resistance useless. At the same time, senior officials of the Nazi party leadership, as well as representatives of SS and police units, insisted on continuing resistance to the last soldier, as Hitler demanded. Due to disagreement definite decision it was not accepted, and the fighting continued. As it became known from the memoirs of Lyash in his book “So Konigsberg Fell”, the head of the East Prussian security service. Boehme, having learned about Lyash’s position, removed him from command with his authority. But this decision was not carried out, because there were no generals in the fortress who wanted to take over the leadership of the doomed troops. And then Boehme himself died, crossing the Pregel. Thus, Lyash continued to command the troops.

Soon after the meeting, Lyash began to act independently. At approximately 18 o'clock, in the sector of the 27th Guards Rifle Regiment, Colonel G. Hefker crossed the front line with the translator Sonderführer Yaskovsky. They were taken to the command post of the 11th Guards Rifle Division. But then there was a hitch. It turned out that the powers given to Hefker were signed not by General Lyash, who sent him, but by Hefker himself. There was concern that this might be a provocation. But Marshal A.M. Vasilevsky decided to take a risk. Parliamentarians were sent to Lyash's headquarters with the text of an ultimatum on unconditional surrender - the chief of staff of the 11th division, Lieutenant Colonel P. G. Yanovsky, captains A. E. Fedorko and V. M. Shpigalnik, who acted as a translator.

This is how retired Major General P. G. Yanovsky later recalled his trip to Lyash’s bunker. The parliamentarians were given only 30 minutes for all the preparation. This was explained by the desire for a quick cessation of hostilities and the approaching twilight. The parliamentarians tidied up their clothes as best they could and left behind their personal documents and weapons. Yanovsky admitted that he was somewhat confused, because he had never had to carry out such tasks, and there were no official instructions on the actions of envoys. In addition, the task was set not only to hand Lyash an ultimatum, but to take him prisoner. But an order is an order, it had to be carried out.

At nineteen o'clock our envoys, accompanied by the German translator Yaskovsky, set off. Colonel Hefker was retained at our headquarters.

The distance from the division headquarters to the location of the German command was small, no more than one and a half kilometers, but it took about two hours to overcome it. The destroyed and burning city, whose streets and alleys were blocked by powerful barricades and engineering barriers, and broken equipment, made a terrible impression. Uncollected corpses lay between the cars. The shooting died down somewhat. It was our artillery that stopped firing, and the planes stopped flying.

A hitch occurred as soon as the envoys found themselves in the zone of German troops. It turned out that Yaskovsky did not know the way to Lyash’s headquarters; he had to go in search of a guide. This turned out to be Lieutenant Colonel B. Kerwin. Thanks to his help, the envoys managed to go the whole way unharmed. The Nazis stopped them three times and even tried to use weapons. Those accompanying the group German officers I had to resolutely come to the defense of the parliamentarians. In the underground bunker where General Lyash’s command post was located, Lieutenant Colonel Yanovsky and his comrades were met by the chief of staff of the encircled group, Colonel von Suskind. He was given one copy of the ultimatum. A few minutes later Lyash entered the room. He carefully read the document and briefly replied that he agreed with its requirements. Then he added that he was taking this step to save the lives of the hundred thousand residents remaining in the city. It was clear to the parliamentarians that it was not just concern for the civilian population, but the real threat of destruction of the Nazi troops surrounded by encirclement that forced the decision to surrender.

It is appropriate here to quote two statements made by General Lyash. On April 4, in his radio address to the troops and population of Koenigsberg, he said: “In order to count on any success in the assault, the Russians will have to gather a huge number of troops. Thank God, they are practically unable to do this.” And on the night of April 9-10, already in captivity, the general admitted: “This is incredible! Supernatural! We have become deaf and blind from your fire. We almost went crazy. No one can stand this..."

This is how Lieutenant Colonel Yanovsky recalls the further development of events. “After Lyash agreed to surrender, we went to his office and at approximately 21:30 began negotiations on the practical implementation decision taken. Lyash and his entourage hoped that we would capture them and deliver them safely to the headquarters of the Soviet troops. My comrades and I could not agree with this, since troops left to their own devices posed the danger of conducting combat operations, albeit scattered, but associated with losses. There was no one to consult with, so we took the initiative into our own hands. They determined the procedure for surrendering German troops, where to lay down light weapons, how to stop the resistance of all troops everywhere, how to communicate the commandant’s decision to the headquarters of units and formations, and even how to ensure the safety of himself and the officers of the defense headquarters.

I demanded that Lyash write a written order to the subordinate troops and deliver them to the units with special liaison officers as soon as possible. At first, Lyash tried to refuse such a step under various pretexts. And when the order was written, it was signed only by the chief of staff, Colonel Suskind. We had to demand that the commandant himself put his signature. By the way, during the negotiations at headquarters there were phone calls, unit commanders asked what they should do. The headquarters officers gave them verbal orders to cease fire and surrender, without waiting for a written order. The commanders did just that.

During the negotiations, the following event occurred. A group of armed SS men, led by the head of one of the departments of the Nazi party chancellery in Königsberg, Lieutenant Colonel Fndler, approached Lyash’s bunker. These fascist fanatics were eager to interrupt the negotiations, shoot the envoys and Lyash himself. But the bunker guards pushed the Nazis back, and we continued our work. This episode excited the German command more than us, who knew what was going on and what the consequences could be. The bitter fate of our envoys in Budapest, killed by Nazi fanatics, was known. Moreover, I allowed the prisoners to have personal weapons with them before crossing the front line. Isn’t it a paradox - we, unarmed envoys, led armed prisoners.”

At the group headquarters, it was decided to leave the head of the operations department to monitor the implementation of the commandant’s order. Our envoys and prisoners crossed the front line again in the sector of the 27th Infantry Regiment. The envoys, along with the prisoners, reached the division headquarters at about one in the morning. There, joyful comrades informed them that an hour ago at 24.00 on April 9, Moscow saluted the valiant troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front, which captured the city and fortress of Konigsberg, with twenty-four artillery salvoes from three hundred and twenty-four guns. In his order, the Supreme Commander-in-Chief thanked the participants in the assault. Subsequently, they were all awarded the medal “For the Capture of Koenigsberg.”

All night and all the next day the surrender of German troops took place. People in civilian clothes approached our soldiers with words of gratitude. These are the ones who were stolen from different countries into fascist captivity and has now been liberated by Soviet troops.

Conclusion

The assault on Koenigsberg is not just one of the brightest episodes of the Great Patriotic War. This is something more that makes us think seriously about many of the problems of today.

Yes, of course, this is a wonderful, talentedly conceived and skillfully executed large-scale military operation. Everything, from the beginning of hostilities on the territory of East Prussia to the capture of the naval fortress of Pillau, to the victorious liberation of this region from fascist troops. No matter how we remember this today, when we have all witnessed the high price paid in war by the military mediocrity of individual high-ranking military officials.

Of course, in the short chronicle story about the assault on Konigsberg, many important pages of the battle are missed; they are covered in more detail in other publications dedicated to this battle. Separately, we can and should talk about the railway troops, which ensured an uninterrupted supply of ammunition, food, and other necessary materials to those going on the assault. It was they who laid, altered and put into operation 552 kilometers in the shortest possible time railway tracks, built 64 bridges. A successful assault on Koenigsberg would have been impossible without the dedicated military work of the engineering and sapper troops. The role of the Baltic Fleet in the assault on Konigsberg and Pillau is invaluable. Ships and submarines cut off enemy sea communications, and naval aviation directly participated in the assault, supporting ground forces.

We must not forget that the attacks on Koenigsberg, wing to wing, with our aviators, were carried out by the French pilots of the Normandy-Niemen regiment, which completed its combat journey on this land. I would also like to mention those who made their invisible contribution to the events that took place. This is a group of German anti-fascists - soldiers, officers and generals from the Free Germany Committee, who, through loud-speaking radio installations put forward in the first lines of attack, appealed to their compatriots not to support the fascist regime. And some of the anti-fascists, knowing full well what this meant, put on military uniforms again and walked across the front line to besieged Koenigsberg to bring the word of truth about the war unleashed by the Nazis into the enemy trenches.

But, most importantly, the storming of Konigsberg once again proved the great power of patriotism. Go to the mass graves, and by the names of the dead you will see that the victory was forged by the sons of all the peoples of the Soviet Union, who never called their homeland “this country.” Touching their feat teaches us to love our country and be proud of its glorious history. And the attempts made by certain circles to alter the results of the Second World War and to downplay the role in it Soviet people, who won great victory over the aggressor who saved the world from the fascist plague.

The official dates of the Koenigsberg operation are April 6 - 9, 1945. Everything is quite short: in three to four days the city was taken. Nevertheless, the assault on the Prussian capital was preceded by sufficient important events- battles for East Prussia.

The very creation and formation of plans for the East Prussian operation began back in November 1944, when our troops from Lithuania reached the borders of the Third Reich. Then Zhukov and Vasilevsky, who was at that time the chief of the General Staff, were summoned to Stalin to plan the operation. It was officially formalized in early December. January 13, 1945 is the official day of its beginning, and April 25 is the day of its end, although individual German units fought almost until the end of the war. The Battle of Königsberg itself is part of this operation.

Hitler called Königsberg "an impregnable bastion of the German spirit"

Many people ask: maybe it would have been worth isolating the German group in East Prussia, holding out until the end of the war and moving on to Berlin? This is impossible for geographical reasons: the territory inhabited by Germans is too large. From there, a strong blow could be delivered to our troops’ flank, and it is almost impossible to block such territory - it is easier to eliminate it.

In addition, there is one more reason: during the war we carried out defensive operations specifically on Kursk Bulge- this is not our style - like in hockey: we have to attack and score goals. This is how we planned this operation: we had to destroy the enemy group to the ground, which, in fact, we did, with some rough edges, but quite successfully.

Soviet artillerymen at a 57-mm ZIS-2 anti-tank gun and soldiers of the assault group are fighting street battles for Königsberg, April 1945

Alexander Mikhailovich Vasilevsky was appointed to the post of commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front on February 18, 1945, while at the Bolshoi Theater. During the performance, an adjutant approached him and said that Stalin was asking him to come to the phone. Vasilevsky heard the sad voice of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, who informed him about the death of the commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front, Army General Chernyakhovsky. “Headquarters intends to place you at the head of the 3rd Belorussian Front,” Stalin concluded.

The assault on Königsberg demonstrated the professionalism of the Red Army

It must be said that during an operation a lot depends on the personality of the front commander himself. Still, Vasilevsky was not such a “man of the people”: his father was a priest (although he abandoned it). Alexander Mikhailovich graduated military school in Moscow (the same as Shaposhnikov, whom he replaced as Chief of the General Staff), received his education back in Imperial Army, therefore, he approached the East Prussian operation more systematically. For the assault on Koenigsberg, a fairly strong group of tanks and self-propelled artillery units was assembled - 634 units. But the main means of combating the long-term structures of the fortified city was artillery, including large and specially powerful ones.

Two Volkssturm riflemen in the trenches near Königsberg, January 1945

A significant role in the defense of Königsberg was played by the famous Gauleiter of East Prussia, Erich Koch, who developed frantic activity in the surrounded city. With all this, he himself behaved like a party leader: periodically he flew to Königsberg by plane, sending telegrams that the Volkssturm detachments would hold the city. And when things got really bad, Koch sailed to Denmark on an icebreaker, which he always kept with him in the port of Pillau, leaving the army to the mercy of fate. German army fought to the end - almost all the officers bore the prefix “von” and were immigrants from East Prussia, descendants of knights. Nevertheless, on April 9, by order of General Lyash, commandant of Königsberg, the German garrison capitulated.

Hitler was enraged by the fall of the city and, in an impotent rage, sentenced Otto von Lyasch to death in absentia. Of course: before that, he declared Koenigsberg “an absolutely impregnable bastion of the German spirit”!

For the surrender of Königsberg, Otto von Lyasch was sentenced to death.

It is worth noting that the so-called SHISBrs - assault engineering and sapper brigades - were involved in the assault on the city. The first two battalions of these brigades were staffed by people under the age of 40. They (visually) wore white camouflage suits, with bulletproof vests on top. That is, it was such an assault infantry. There were flamethrowers and miners in the department. The tactical technique they worked out was quite original: the heavy self-propelled gun SU-152 hit the upper floors of buildings, preventing the Germans from conducting any fire; at that moment, a tank equipped with an anchor was pulling away the barricades; after that, a group of stormtroopers took over, first burning everything out with a flamethrower, and then clearing the building. That is, our fighters at that time were very prepared. This was already an army of winners, which realized that it was moving forward to win; it had no fear of the Germans. Many peoples of Europe surrendered as soon as the Third Reich started the war, but we did not have this fear.

German soldiers captured after the assault on Königsberg, April 9, 1945

Nevertheless, the battle for Königsberg became one of the bloodiest clashes of the Great Patriotic War. Yes, interestingly, there were practically no SS formations in the Prussian capital itself. At that time, all of Hitler’s elite units were on the southern flank, in the Lake Balaton area. And in general, in the entire East Prussian operation, only the “Grossdeutschland” division can be classified as elite SS units (although, if you look at it, it was an elite formation of the Wehrmacht), and the “Hermann Goering” division ( elite unit Luftwaffe). But they no longer took part in the battles for Königsberg. To repel enemy attacks, the Germans created detachments people's militia(Volkssturm), which, let’s say, fought in different directions: some units were persistent (due to internal, subjective reasons), some simply fled.

Yes, on the one hand, the German army defended itself steadfastly, but, on the other, where could it run? Koenigsberg itself was cut off, there was no way to evacuate. However, the prevailing idea among the German population was that it was necessary to hold out as long as possible: the allies would disperse among themselves political views, and Germany will somehow survive and not turn into a potato field. That is unconditional surrender can be avoided. However, this did not happen.

In honor of the capture of Königsberg, a salute of the highest category was given in Moscow

Returning to the battle itself. As for losses, on our part for the entire East Prussian operation, the official, approved and published data is 126 thousand 646 people. For strategic offensive operation These are average indicators - not outstanding, but not small either. The Germans had much greater losses - about 200 thousand people, since most of the population was not evacuated because of Koch, all the men were called up to the Volkssturm.

During the Koenigsberg operation, almost the entire city was destroyed. And yet, for the sake of objectivity, it must be said that the fortress was damaged back in 1944 after the British bombing. It is not entirely clear why our allies did this: after all, there was no large quantity military enterprises, they were concentrated in two places - in the Ruhr and Upper Silesia.

On the streets of Königsberg after the assault, April 10, 1945

And yet, the decision of the Headquarters to storm Koenigsberg was more military than political. East Prussia is too large a territory, and to cut it off from the rest of the Reich and clean it up, it took the efforts of the fleet, two fronts, and aviation. In addition, the capture of Königsberg also had some symbolic meaning - after all, “the citadel of Prussian militarism.” By the way, the father of Generalissimo Suvorov was once the Governor-General of East Prussia. Of course, ordinary soldiers hardly thought about this; they had one desire - to end this war as quickly as possible.

10.04.2015 0 11697

« Fight for Konigsberg- this is an episode of the great battle with our Slavic neighbor, which had such a terrible impact on our fate and the fate of our children and whose influence will be felt in the future."- these words belong to the commander of the Koenigsberg garrison, General Otto von Lashu.

The name of the city he defended is no longer on geographical map. There is a city Kaliningrad- the center of the region of the same name of the Russian Federation, surrounded from the west, east and south by the countries of the European Union and washed from the north by the Baltic Sea; the only small but important territorial prize that the Soviet Union received after the defeat of Germany.

"The Cradle of PRUSSIAN MILITARISM"

Goebbels's diary entries, dating from early April 1945, contain an interesting admission concerning little-known contacts between Soviet and German representatives in Stockholm. Discussing the theoretical possibility of concluding a separate peace, Mr. Reich Minister was indignant that the Kremlin was demanding East Prussia, but “this, of course, is completely unacceptable.”

View of one of the Königsberg forts

In fact, the fascists should have grabbed such a proposal with their hands and feet, however, both Goebbels and his beloved Fuhrer in this (by no means the only case) attached a certain sacred significance to the East Prussian lands, as a kind of outpost of Germany in the east.

Let us again give the floor to General von Lyash: “Königsberg was founded in 1258 by the German order of chivalry in honor of King Ottokar of Bohemia, who participated in the order’s summer campaign to the East. The castle, the construction of which began during the founding of the city, was its first defensive structure. In the 17th century, the city was fortified with a rampart, ditches and bastions, thus becoming a fortress. These structures gradually deteriorated and did not serve much service either in the Seven Years' War or in the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1814, Koenigsberg was declared an open city, but in 1843 its fortification began again, and what was then called a fortress fence was erected, that is, a ring of fortifications around the city with a length of 11 kilometers. Their construction was completed in 1873. In 1874, construction began on a defensive belt of 15 forward forts, the construction of which was completed in 1882. To protect the mouth of the Pregel, a strong fortification was built on the right bank near the Holstein estate. The fortification of Friedrichsburg on the left bank of the mouth of the Pregel was even stronger.”

Let us note several episodes not mentioned by von Lyash. It was based on Koenigsberg that the German knights waged their campaigns against the Prussians, which ended in the physical destruction or assimilation of this people, who gave their name to the region. In 1758, during the Seven Years' War, Koenigsberg was occupied by Russian troops, and its residents were sworn in to Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, and it is interesting that among those who took it was Emmanuel Kant, a professor at the local university. However, in 1762 a new Russian Emperor Peter III with a sweeping gesture he returned East Prussia to his idol Frederick the Great.

In 1806-1807, the city was actually the capital of the Kingdom of Prussia, since it was here that “beyond friendly bayonets” Russian army Frederick William III, beaten by Napoleon, took refuge.