Emperor Paul I is one of the most mysterious and tragic figures on the Russian royal throne. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark is a character from the tragic play of the same name by William Shakespeare, which brought fame to its creator. But what do the Russian emperor and the Danish prince, the hero of a play banned in the Russian Empire, have in common? Why was Paul I called the Russian Hamlet?

Upon closer examination, the fates of these individuals are not only similar, but sometimes exactly repeat each other. Even the two heroes received the same impeccable education. Pavel was fluent in French, Italian, Latin and German languages Hamlet received an excellent military education and was an impeccable swordsman.

It all started with the palace coup of Catherine II in real life, which ended with the death of Peter III, Paul's father, and with the brutal murder of the Danish king, Hamlet's father, at the hands of his uncle.

The young emperor would return to the events of 1762, which Paul I was not yet able to comprehend at that time, over and over again, thereby irrevocably crippling his soul and creating a starting point for talking about his “madness.”

Pavel Petrovich longed to know the secrets that shrouded the death of his father and the coup organized by his own mother and wanted only one thing - the restoration of justice, the clearing of the name of Peter III and the reduction of the merits of Catherine II. These aspirations make him similar to the hero of the English playwright, who desired the same in relation to his murdered father.

These two personalities are brought together by the terrible losses they had to endure. In the life of the young emperor, such a blow was the death of his beloved, Natalya Alekseevna. The Grand Duchess died in childbirth, giving birth to a stillborn prince.

Pavel was left alone, no longer having a lady close to his heart, no parents, no associates. The death of Ophelia, the beloved of the Danish prince, resonates with the same pain in the soul of Hamlet himself. The life of a young girl was carried away by the waters of the ill-fated river: “...She tried to hang her wreaths on the branches; the treacherous branch broke, and the grass and she herself fell into the sobbing stream. Her clothes, spread out, carried her like a nymph; Meanwhile, she sang snippets of songs, as if she did not sense trouble or was a creature born in the element of water; this could not last, and the clothes, heavily drunk, carried the unfortunate woman into the quagmire of death from the sounds.”

Having always been a “black sheep” among the depraved servants of Catherine II, the future emperor forever formed for himself one of the goals of his reign - to destroy all the privileges of the nobility, no matter what they were. It was in the pillar of power of his mother - the nobility, that Paul saw the guilt of the unstable social system of the Russian Empire. But he did not agree not only with the “noble” policy of the All-Russian Empress, but also with her attitude to faith and its place in the life of the state. Raised as a devout child since childhood, he could not understand a woman to whom “everything holy is alien.” The inability to come to terms with the policies of the ruling mother, countless attempts by Catherine’s deprived favorites to involve Paul in a conspiracy against her - all this influenced the psyche of the future emperor. “Nervous irritability,” points out S. Platonov, led him to painful attacks of severe anger.” And Pavel Lopukhin assured: “Paul’s irritability did not come from nature, but was the consequence of one attempt to “poison” him.” Paul, like Hamlet, managed to avoid the first reprisal against himself, but they could not change their fate - they both faced violent death at the hands of selfish traitors.

But let us return again to “madness” - one of the connecting links between Paul I and Hamlet. But if the Danish prince played a son who had lost his mind, then Pavel literally teetered on the brink of madness, so different was his behavior from the generally accepted norms of that time. It was easier for the nobility to recognize him as crazy than to understand and accept his principles. It must be admitted that separation and misunderstanding with his mother, deprivation of parental love and warmth, lonely life at his grandmother’s court left their mark on the soul of little Pavel! But even though the emperor was subject to the passions and emotions raging in his soul, at the heart of his character lay a steel core - chivalrous, noble feelings that were noticed by all the court people. Later, De Sanglen would write in his memoirs: “Paul was a knight of times gone by.”

During his reign, Paul the First did not execute anyone

Historical science has never known such a large-scale falsification as the assessment of personality and activity Russian Emperor Paul the First. After all, what about Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Stalin, around whom polemical spears are now mostly breaking! No matter how you argue, “objectively” or “biasedly” they killed their enemies, they still killed them. And Paul the First did not execute anyone during his reign.

He ruled more humanely than his mother Catherine the Second, especially in relation to ordinary people. Why is he a “crowned villain,” in Pushkin’s words? Because, without hesitation, he fired negligent bosses and even sent them to St. Petersburg (about 400 people in total)? Yes, many of us now dream of such a “crazy ruler”! Or why is he actually “crazy”? Yeltsin, excuse me, sent some needs in public, and he was considered simply an ill-mannered “original.”

Not a single decree or law of Paul the First contains any signs of madness; on the contrary, they are distinguished by reasonableness and clarity. For example, they put an end to the madness that was happening with the rules of succession to the throne after Peter the Great.

The 45-volume “Complete Code of Laws of the Russian Empire,” published in 1830, contains 2,248 documents from the Pauline period (two and a half volumes) - and this despite the fact that Paul reigned for only 1,582 days! Therefore, he issued 1-2 laws every day, and these were not grotesque reports about “Second Lieutenant Kizha,” but serious acts that were later included in the “Complete Code of Laws”! So much for “crazy”!

It was Paul I who legally secured the leading role Orthodox Church among other churches and denominations in Russia. The legislative acts of Emperor Paul say: “The primary and dominant faith in the Russian Empire is the Christian Orthodox Catholic of the Eastern Confession”, “The Emperor, who possesses the All-Russian Throne, cannot profess any other faith than the Orthodox.” We will read approximately the same thing in the Spiritual Regulations of Peter I. These rules were strictly observed until 1917. Therefore, I would like to ask our adherents of “multiculturalism”: when did Russia manage to become “multi-confessional”, as you are now telling us? During the atheistic period 1917–1991? Or after 1991, when the Catholic-Protestant Baltics and the Muslim republics of Central Asia “fell away” from the country?

Many Orthodox historians are wary of the idea that Paul was Grand Master Order of Malta(1798–1801), considering this order a "para-Masonic structure".

But it was one of the main Masonic powers of the time, England, that overthrew Paul’s rule in Malta by occupying the island on September 5, 1800. This at least suggests that Paul was not recognized in the English Masonic hierarchy (the so-called “Scottish Rite”) yours. Maybe Paul was “one of the people” in the French Masonic “Grand Orient” if he wanted to “make friends” with Napoleon? But this happened precisely after the British captured Malta, and before that Paul fought with Napoleon. We must also understand that Paul I required the title of Grand Master of the Order of Malta not only for self-affirmation in the company of European monarchs. In the calendar of the Academy of Sciences, according to his instructions, the island of Malta was to be designated as a “province Russian Empire" Pavel wanted to make the title of grandmaster hereditary and annex Malta to Russia. On the island, he planned to create a naval base to ensure the interests of the Russian Empire in the Mediterranean Sea and southern Europe.

Finally, it is known that Paul favored the Jesuits. This is also blamed by some Orthodox historians in the context of the complex relationship between Orthodoxy and Catholicism. But there is also a specific historical context. In 1800, it was the Jesuit Order that was considered the main ideological enemy of Freemasonry in Europe. So the Freemasons could in no way welcome the legalization of the Jesuits in Russia and treat Paul I as a Freemason.

THEM. Muravyov-Apostol more than once spoke to his children, the future Decembrists, “about the enormity of the revolution that took place with the accession of Paul the First to the throne - a revolution so drastic that descendants would not understand it,” and General Ermolov argued that “the late emperor had great traits , its historical character has not yet been determined for us.”

For the first time since the time of Elizabeth Petrovna, serfs are also taking an oath to the new tsar, which means they are considered subjects, not slaves. Corvée is limited to three days a week with days off on Sundays and holidays, and since Orthodox holidays there are many in Rus', this was a great relief for the working people. Paul the First forbade the sale of courtyards and serfs without land, as well as separately if they were from the same family.

As in the time of Ivan the Terrible, in one of the windows Winter Palace a yellow box is installed where everyone can throw a letter or petition addressed to the sovereign. The key to the room with the box was kept by Pavel himself, who every morning himself read the requests of his subjects and printed the answers in the newspapers.

“Emperor Paul had a sincere and strong desire to do good,” wrote A. Kotzebue. - Before him, as before the kindest sovereign, the poor man and the rich man, the nobleman and the peasant, were all equal. Woe to the strong man who arrogantly oppressed the poor. The road to the emperor was open to everyone; the title of his favorite did not protect anyone in front of him...” Of course, the nobles and rich, accustomed to impunity and living for free, did not like this. “Only the lower classes of the urban population and peasants love the Emperor,” testified the Prussian envoy to St. Petersburg, Count Bruhl.

Yes, Pavel was extremely irritable and demanded unconditional obedience: the slightest delay in the execution of his orders, the slightest malfunction in the service entailed the strictest reprimand and even punishment without any distinction. But he is fair, kind, generous, always friendly, inclined to forgive insults and ready to repent of his mistakes.

However, the best and good undertakings of the king were dashed against the stone wall of indifference and even obvious ill will of his closest subjects, outwardly loyal and servile. Historians Gennady Obolensky in the book “Emperor Paul I” (M., 2001) and Alexander Bokhanov in the book “Paul the First” (M., 2010) convincingly prove that many of his orders were reinterpreted in a completely impossible and treacherous manner, causing an increase in hidden discontent with the tsar . “You know what kind of heart I have, but you don’t know what kind of people they are,” Pavel Petrovich wrote bitterly in one of his letters about his environment.

And these people vilely killed him, 117 years before the murder of the last Russian sovereign, Nicholas II. These events are certainly connected; the terrible crime of 1801 predetermined the fate of the Romanov dynasty.

Decembrist A.V. Poggio wrote (by the way, it is curious that many objective testimonies about Paul belong precisely to the Decembrists): “... a drunken, violent crowd of conspirators breaks into him and disgustingly, without the slightest civil purpose, drags him, strangles him, beats him... and kills him! Having committed one crime, they completed it with another, even more terrible one. They intimidated and captivated the son himself, and this unfortunate man, having bought a crown with such blood, throughout his reign will languish over it, abhor it and involuntarily prepare an outcome that will be unhappy for himself, for us, for Nicholas.”

But I would not, as many admirers of Paul do, directly contrast the reigns of Catherine the Second and Paul the First. Of course, Paul's moral character in better side differed from the moral character of the loving empress, but the fact is that her favoritism was also a method of government, which was not always ineffective. Catherine needed her favorites not only for carnal pleasures. Kindly treated by the Empress, they worked hard, God willing, especially A. Orlov and G. Potemkin. The intimate proximity of the empress and her favorites was a certain degree of trust in them, a kind of initiation, or something. Of course, there were slackers and typical gigolos like Lansky and Zubov next to her, but they appeared already in last years Catherine’s life, when she somewhat lost her grasp of reality...

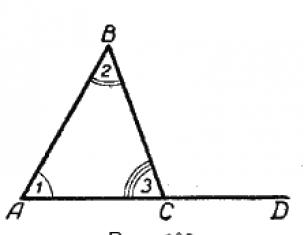

Another thing is Paul's position as heir to the throne under a system of favoritism. A. Bokhanov writes: in November 1781, “the Austrian Emperor (1765–1790) Joseph II arranged a magnificent meeting (for Paul. - A. B. ), and in the sequence special occasions A performance of Hamlet was scheduled at court. What happened next was that lead actor Brockman refused to perform main role, since, according to him, “there will be two Hamlets in the hall.” The emperor was grateful to the actor for his wise warning and awarded him 50 ducats. Pavel did not see Hamlet; It remains unclear whether he knew this tragedy of Shakespeare, the external plot of which was extremely reminiscent of his own fate.”

And diplomat and historian S.S. Tatishchev told the famous Russian publisher and journalist A.S. Suvorin: “Paul was Hamlet in part, at least his position was Hamlet’s; Hamlet was banned under Catherine II,” after which Suvorin concluded: “Indeed, it’s very similar. The only difference is that instead of Claudius, Catherine had Orlov and others...” (If we consider young Pavel as Hamlet, and Alexei Orlov, who killed Paul’s father Peter III, as Claudius, then unfortunate Peter will be in the role of Hamlet’s father, and Catherine herself will be in the role of Hamlet’s mother Gertrude, who married the murderer of her first husband).

Paul's position under Catherine was indeed Hamlet's. After the birth of his eldest son Alexander, the future Emperor Alexander I, Catherine considered the possibility of transferring the throne to her beloved grandson, bypassing her unloved son.

Paul's fears in this development of events were strengthened by Alexander's early marriage, after which, according to tradition, the monarch was considered an adult. On August 14, 1792, Catherine II wrote to her correspondent Baron Grimm: “First, my Alexander will get married, and then over time he will be crowned with all sorts of ceremonies, celebrations and folk festivals.” Apparently, that’s why Pavel pointedly ignored the celebrations on the occasion of his son’s marriage.

On the eve of Catherine's death, the courtiers were waiting for the publication of a manifesto on the removal of Paul, his imprisonment in the Estonian castle of Lode and his proclamation as Alexander's heir. It is widely believed that while Paul was awaiting arrest, Catherine’s manifesto (testament) was personally destroyed by cabinet secretary A. A. Bezborodko, which allowed him to receive the highest rank of chancellor under the new emperor.

Having ascended the throne, Paul solemnly transferred his father’s ashes from the Alexander Nevsky Lavra to the royal tomb of the Peter and Paul Cathedral at the same time as the burial of Catherine II. At the funeral ceremony, depicted in detail on a long painting-ribbon by an unknown (apparently Italian) artist, the regalia of Peter III - the royal staff, the scepter and the large imperial crown - were carried by... the regicides - Count A.F. Orlov, Prince P.B. Baryatinsky and P.B. Passek. In the cathedral, Paul personally performed the ceremony of coronation of the ashes of Peter III (only crowned persons were buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral). In the headstones of the tombstones of Peter III and Catherine II, the same date of burial was carved - December 18, 1796, which may give the uninitiated the impression that they lived together for many years and died on the same day.

Invented in Hamlet style!

In the book by Andrei Rossomakhin and Denis Khrustalev “The Challenge of Emperor Paul, or the First Myth of the 19th Century” (St. Petersburg, 2011) for the first time, another “Hamlet” act of Paul I is examined in detail: the challenge to a duel that the Russian emperor sent to all the monarchs of Europe as an alternative to wars in which tens and hundreds of thousands of people die. (This, by the way, is exactly what L. Tolstoy, who himself did not favor Paul the First, rhetorically proposed in “War and Peace”: they say, let emperors and kings fight personally instead of destroying their subjects in wars).

What was perceived by contemporaries and descendants as a sign of “madness” is shown by Rossomakhin and Khrustalev as a subtle game of the “Russian Hamlet” that was cut short during a palace coup.

Also, for the first time, evidence of the “English trace” of the conspiracy against Paul is convincingly presented: thus, the book reproduces in color English satirical engravings and caricatures of Paul, the number of which increased precisely in the last three months of the emperor’s life, when preparations began for the conclusion of the military-strategic alliance of Paul with Napoleon Bonaparte. As is known, shortly before the murder, Pavel gave the order to an entire army of Cossacks of the Don Army (22,500 sabers) under the command of Ataman Vasily Orlov to set out on a campaign to India, discussed with Napoleon, in order to “disturb” English possessions. The Cossacks’ task was to conquer Khiva and Bukhara “in passing”. Immediately after the death of Paul I, Orlov’s detachment was recalled from the Astrakhan steppes, and negotiations with Napoleon were curtailed.

I am sure that the “Hamlet theme” in the life of Paul the First will still become the subject of attention of historical novelists. I think there will also be a theater director who will stage “Hamlet” in the Russian historical interpretation, where, while preserving Shakespeare’s text, the story will take place in Russia at the end of the 18th century, and Tsarevich Pavel will play the role of Prince Hamlet, and the ghost of Hamlet’s father will play the role of Prince Hamlet. killed Peter III, in the role of Claudius - Alexey Orlov, etc. Moreover, the episode with the play performed in “Hamlet” by the actors of the traveling theater can be replaced with an episode of the production of “Hamlet” in St. Petersburg by a foreign troupe, after which Catherine II and Orlov will ban the play. Of course, the real Tsarevich Pavel, finding himself in the position of Hamlet, outplayed everyone, but still, after 5 years, the fate of Shakespeare’s hero awaited him...

Special for the Centenary

The AST-Press publishing house published the book “Russian Hamlet. Paul I, the rejected emperor." In it, Elena Horvatova, the author of many interesting publications on Russian history, presents A New Look on Paul I, refuting established stereotypes and existing myths. "Private Correspondent" publishes excerpts from the book, kindly provided by the publisher.

Preface

Emperor Paul I is one of the most mysterious and tragic figures on the Russian throne. Rare rulers were treated with such prejudice, rarely were they judged only on the basis of gossip and speculation, without even making an attempt to think about the true motives of his actions, and rare people were so high level have been surrounded by a veil of secrecy for so long. And Pavel Petrovich’s wife (second wife, to be precise) Maria Feodorovna is truly a forgotten empress. Even experts national history they can tell little about this woman. Some kind of faded shadow behind the back of a nervous, eccentric husband who had poor control of his emotions - this is a widely held opinion. Not knowing about the true role of Empress Maria in politics, court life, and the intrigues of the Romanov dynasty, many deny her intelligence, bright passions, and strength of personality.

In March 1801, it turned out that Paul had to fall, Alexander - to reign. His son did not participate in the conspiracy that killed Paul I, but he knew about the plans of the conspirators and did nothing to save his father-sovereign. Emperor Paul tried to take away the privileges granted by Catherine from the nobility. And by subjecting demoted officers to corporal punishment, the tyrant violated the sacred principle of the inviolability of the noble back!

An ordinary German princess, taken out of mercy as the wife of the widowed heir to the Russian throne... What were her interests? To give birth to children in order to ensure the continuation of the royal family, and to please those on whom her life depended - first the all-powerful mother-in-law, Empress Catherine II, then her husband, whose character became more and more complex over the years. Meanwhile, Maria Fedorovna, or, as her maiden name was, Sophia Dorothea Augusta of Württemberg, was an extraordinary person - a beauty, an intellectual, she had a subtle mind, was distinguished by diplomatic abilities, her own ideas about the good of Russia, and often held in her hands secret threads that forced the flow of history changes its usual course.

Were Paul and Mary bound by love? Without a doubt. But like any long-lasting feeling, their love experienced ups and downs, and sometimes even betrayal. However, this love survived despite everything and glowed even in the last, tragic days of the reign and life of Emperor Paul.

Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin called Paul I a “romantic emperor” and was going to write the history of his reign. Alexander Herzen has an even more vivid definition: “crowned Don Quixote.” Leo Tolstoy spoke about Pavel in one of his personal letters: “I have found my historical hero. And if God gave life, leisure and strength, I would try to write his story.” Unfortunately, these plans were never realized. But a careful and unbiased look at the events of the life and reign of Emperor Paul could change the attitude towards this man and open up pages of history that have remained unknown to this day...

Chapter first

Emperor Paul was born into the family of the heir to the Russian throne, Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, grandson of Peter I, and the Anhalt-Zerbst princess Sophia Augusta Frederica. In 1745, shortly before the wedding, Sofia Augusta Frederica converted to Orthodoxy and received the name Ekaterina Alekseevna. A dynastic marriage, built on dubious benefits, was initially doomed to become unhappy, so it was difficult to call the union of these two people a family. According to the famous historian V.O. Klyuchevsky, young Catherine went to Russia with dreams of the Russian crown, and not of family happiness: “She decided that in order to realize the ambitious dream that had sunk deep into her soul, she needed to be liked by everyone, first of all the empress, her husband and the people.” Therefore, the young wife of the heir tried not to contradict anyone, not to show her ambitious character in any way and demonstrated only humility and goodwill. Catherine herself confirmed this in her memoirs. “I can’t say that I liked him or didn’t like him,” she wrote about her husband, Peter III, “I only knew how to obey. It was my mother's job to marry me off. But in truth, I think that I liked the Russian crown more than his person... We never spoke to each other in the language of love: it was not for me to start this conversation.”

During the first years of her stay in Russia, Catherine lived under strict control and had no influence either on political events or court intrigues. Lonely, unloved, deprived of loved ones and friends, she found solace in books. Tacitus, Voltaire, Montesquieu became her favorite authors.

The relationship with her husband, despite all her efforts, did not work out: he is rude and ignorant, Grand Duke Peter humiliated and insulted her in every possible way. The birth of his son Paul in 1754 did not make any changes in their family life. By order of Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, Catherine’s newborn son was immediately taken away - the empress, as a great-aunt, wished to take care of raising the boy herself.

The birth and all subsequent events remained one of Catherine’s most bitter memories. The barely born boy, washed and swaddled, found himself in the hands of Elizaveta Petrovna, who solemnly placed the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called on the baby on a blue moire ribbon. The mother was not really shown the baby. The Empress, the Grand Duke and the courtiers present at the birth immediately left to present the newborn Grand Duke to the representatives of high society who filled the halls of the palace. A woman in labor who needed help was simply forgotten, abandoned in a cold and damp room. Only one court lady remained with her, a rather callous person who was too obsequious to the empress to show even a drop of independence in relation to the unfortunate Catherine. The young mother lost a lot of blood, became weak, and suffered from thirst, but no one cared. “I remained lying on a terribly uncomfortable bed,” recalled Ekaterina. “I was sweating a lot and begged Madame Vladislavleva to change the bed linen and help me get onto the bed. She replied that she did not dare to do so without permission.”

For three hours, the weakening woman in labor suffered in a bed soaked with blood and sweat, under a thin, prickly blanket that did not protect against the piercing cold. She was shaking with chills, her dry lips were cracked, and her tongue was barely moving in her mouth when State Lady Shuvalova accidentally looked in the door.

Fathers of light! - she exclaimed. - So it won’t take long to die!

Maids appeared near Catherine with warm water and clean linen, and a fuss began... But the Grand Duchess managed to catch a bad cold, was between life and death for several days and was not even able to attend her son’s baptism. The boy's name was chosen by Elizaveta Petrovna. However, she was not going to consult with anyone either about the name or about the upbringing of the boy, declaring to the parents that the son belonged not to them, but to the Russian state.

A week after giving birth, Catherine received a package of gifts from the Empress. It contained a necklace, earrings, a pair of rings and a check for one hundred thousand rubles. The amount seemed fantastic to the unspoiled princess, but Catherine was not pleased with either the money or the jewelry. She already realized that, having given birth to an heir, she had fulfilled her main mission and became of no use to anyone; Now she can be discounted at any moment...

Paul's childhood was very sad and orphaned, although it was spent in the luxury of royal palaces. He did not know parental love. The father was not particularly interested in his son’s life, and Pavel was separated from his mother. Elizaveta Petrovna did not have her own children, at least no official children, whom she would raise herself (all sorts of rumors circulated about the empress’s illegitimate children). She had very rough ideas about exactly how babies should be raised. But Elizabeth was enthusiastically busy playing with a living doll, who was her great-nephew. The people assigned to care for little Pavel considered the main task to be the fulfillment of all the instructions, orders, whims and whims of the empress, without reasoning or even thinking about whether this would be for the benefit of the child or for harm. Elizaveta Petrovna once mentioned that the boy should be wrapped warmer in order to avoid colds. The unfortunate baby lay in a well-heated room, dressed in a bunch of clothes and caps, tightly swaddled, covered with a thick quilted blanket with cotton wool and another, brocade, lined with the fur of silver foxes... He was sweating, crying and suffocating from the heat, unable to move neither arm nor leg.

Catherine, who was rarely allowed to see her son, on special occasions, recalled this picture with horror and it was precisely this “hothouse” upbringing that explained Pavel’s further tendency to catch colds from the slightest draft. No one listened to the mother’s requests to at least remove the baby’s fur and unwrap him. Would the servants have decided to violate the order of the Empress in order to please the German upstart Catherine, who was taken to the Russian court out of favor?

That's how it went. If Elizaveta Petrovna, busy with the next celebration, forgot to order the child to be fed, Pavel remained hungry. But if there was an order to feed the boy, he was stuffed with food to the fullest and severely overfed. If the highest order was not received to take Pavel out for a walk, he would sit in the stuffiness, without fresh air.

They started teaching him at the age of four - too early for such a kid. The Empress did not think that this great stress for the fragile child’s psyche could subsequently lead to nervous disorder. It seemed to Elizabeth that it was time, because at four years old the boy was quite smart. So she ordered, as a matter of fact, to teach literacy and other subjects to Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich, let him grow up educated. From then on, Pavel spent his entire childhood doing nothing but mastering various sciences.

The teachers had to show a lot of ingenuity so that their little student could overcome the teaching. For example, the letters of the alphabet were written on the backs of toy soldiers, and Paul had to build his army in such a way that words and then phrases were obtained. It was a study, but at the same time a game, which reconciled the baby with life. Meanwhile, the empress began to get tired of the living toy.

The older Pavel got, the less funny he seemed. He was moved from Elizaveta Petrovna’s chambers to a separate wing. The Empress's visits to Grand Duke Paul became less and less frequent. The boy was provided only with nannies and educators. The mother, separated from her child, was sad and suffered, but she was forbidden to even openly demonstrate her suffering. As a result, her feelings for her son, locked in some distant corner of her consciousness, cooled and somehow faded. The impossibility of everyday communication deprived them of real warmth and cordiality.

In 1761, after the death of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna and the accession of Peter III to the throne, Catherine’s position at court not only worsened, but became dangerous. The husband did not hide his hatred of her and openly lived with his mistress. The issue of divorce and subsequent sending of the disgraced wife to a monastery was practically resolved. And Peter did not have any warm feelings for his son, although Empress Elizabeth, before her death, made her nephew promise to love little Paul. But Peter III did not want to recognize his son as his heir, and even in the manifesto on his accession to the throne, in violation of all traditions, he did not mention his name.

However, the position of Peter III was not so strong: the new emperor, who clumsily took his first steps in the public sphere, irritated the highest circles and the army. He had almost no sincere followers. Catherine, who was sensitive to the slightest changes in the mood at court, realized that fate was giving her a chance to change her fate. She immediately had other worries besides flawed motherhood - political intrigues, preparations for a coup, the removal of her husband from power, and then his physical removal from the historical arena... At first, she only counted on defending her and her son’s interests, but the struggle for power so captivated her that her original goals were forgotten in the process of this struggle.

On June 28, 1762, Catherine, with the help of guards regiments led by brothers Alexei and Grigory Orlov, carried out a coup d'etat, concentrating power in her hands. Peter III was deposed, placed under house arrest in a deserted country estate and was soon killed by supporters of the new mistress of Russia.

On September 22, 1762, the coronation ceremony of Empress Catherine II took place in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. At the time of these events, Paul was an eight-year-old child, and no one took into account his interests, including in the sphere of succession to the throne, although it was he who was supposed to succeed his father on the throne. After all, the legitimate sovereign Peter III (no matter how his subjects treated his personality, Elizabeth gave the royal crown to him) had a legal heir, Tsarevich Pavel Petrovich.

The Dowager Empress Catherine (whose widowhood, as everyone understood, was arranged by her own diligence) could, at best, become regent for her young son and rule until Paul came of age. But the eighteenth century was the century of adventurers...

IN. Klyuchevsky noted: “The June coup of 1762 made Catherine II an autocratic Russian empress. From the very beginning of the 18th century, the bearers of supreme power in our country were either extraordinary people, like Peter the Great, or random people, like his successors and successors, even those who were appointed to the throne by virtue of the law of Peter I by a previous accident, as it was. .. with Peter III. Catherine II closes the series of these exceptional phenomena of our not entirely orderly 18th century: she was the last accident on the Russian throne and led a long and extraordinary reign, creating an entire era in our history.”

In 1762, due to his youth, Pavel could not comprehend what was happening in his family and state. But over time, he will return to these events in his thoughts more than once. And the older Paul gets and the more he learns about the recent past, the deeper the breakdown will go in his soul...

There was a version that Paul was not the son of Peter III at all. The boy’s father allegedly became Sergei Saltykov, who “comforted” Grand Duchess Catherine, when her husband showed her complete neglect. A famous historical anecdote (which could well have been real fact) says that the great-grandson of Paul I, Emperor Alexander III became preoccupied with the question of his own origin and invited prominent historians to come to him to clarify the matter.

“What do you think, gentlemen,” he turned to the learned men, “could Saltykov be the father of Paul I?”

Without a doubt, Your Majesty,” one of the historians replied. - After all, Empress Catherine herself hints at this in her memoirs. What does it hint at, it simply says that her husband was incapable of fulfilling his marital duty... This means that Pavel’s father is Saltykov.

“Thank God,” Emperor Alexander crossed himself, “that means we have Russian blood!” 1

Your Majesty, I completely disagree with this,” objected another scientist, an expert on the 18th century. - Compare the portraits of Peter III and Paul I. The family resemblance is simply striking. It is clear that Paul is his father's son. And Catherine, due to historical circumstances, was interested in defaming her deposed husband in every possible way in order to prove his worthlessness. Forgive me generously, but she slandered Peter!

“Thank God,” the emperor crossed himself, “that means we are legitimate!”

Chapter thirty-seven

When the fateful hour struck, a crowd of drunken guardsmen led by Nikolai and Platon Zubov, inciting each other, headed to the emperor’s bedroom.

He was practically doomed - the conspirators no longer thought about saving the sovereign’s life. Pushkin wrote about Paul and the events of the fateful night in Mikhailovsky Castle:

- He sees: in ribbons and stars,

Drunk with wine and anger,

Hidden killers are coming,

There is insolence on their faces, fear in their hearts...

But Paul did not see, but rather felt their approach, perhaps heard the clatter of boots, the ringing of spurs and voices shamelessly shouting in the emperor’s chambers as he rested. In the half-empty halls of the new castle, sounds carried far away... Pavel's worst nightmares came true. He was afraid of death, but was internally prepared for it to happen, he even waited for the outcome, but... as it turned out, he was never able to take the necessary measures to protect himself.

And yet it is difficult to get rid of the thought that the Troubles were organized by the Romanovs in order to ascend to the Russian throne. And since history is written by the victors, sometimes suspicions even creep in that Tsarevich Dmitry was ordered by the Romanov clan, and not the Godunov clan. And one can imagine that if the Godunov dynasty had strengthened on our throne, Pushkin could well have written the tragedy “Fyodor Romanov.” Approximately the same text that we study at school, only the words “Yes, pitiful is the one whose conscience is not clear” would be spoken by Fyodor Nikitich.

The steps are getting closer. Run? Where? Towards the killers? This will only speed up the outcome. In the adjoining bedroom to the Empress? He locked the door himself, and you won’t soon find the key in the turmoil... Along the secret staircase to the upper chambers to Annushka? There was no entrance directly from the bedroom, the door to the stairs was too far away, and the enemies were close, cutting off the path... And not a single loyal person nearby. The emperor did not foresee everything. The castle would have withstood a rebel siege; its cannons could have been used to shoot enemy troops at distant approaches, but Pavel never expected to find himself in his own bedroom alone with a crowd that wanted his death. And yet I didn’t want to believe that this was the end. Maybe there is at least one tiny chance left for salvation?

Pavel jumped up from his bed (it was a narrow folding camp bed, under which you could not hide) and rushed around the bedroom. Where to hide? There were almost no such places, except behind a screen... The shelter was unreliable, but what if a miracle happened and they didn’t find him? He ran behind an elegant low screen that stood by the fireplace, bent down and fell silent, trying almost not to breathe.

The conspirators burst into the room. Platon Zubov was the first to rush through the door. He slipped through and immediately backed away - there was more fear and uncertainty in his soul than determination. Bennigsen, who followed him, again pushed the former Tsarina’s favorite into Pavel Petrovich’s bedroom. Zubov saw that the bed was empty and the emperor was nowhere to be found. If Pavel had gotten used to the idea that assassins might attack him, then Platon Zubov, for his part, was also internally prepared for the fact that nothing would come of the coup idea and he would have to answer for everything. However, Zubov tried not to show his own fear to others. Cursing, Plato casually said in French:

The bird has flown away!

He was afraid to search the emperor’s chambers, he wanted to escape as quickly as possible, then maybe everything would work out... If all the conspirators were like Zubov, Pavel Petrovich would really have a chance to survive. Even a pitiful screen could save his life. But others were determined to go all the way. Among them there were many military officers with military experience different from that of Zubov, who received his ranks in Catherine’s bedroom. The cool-headed Bennigsen immediately guessed where he could hide and threw the screen aside. The Emperor, in a nightgown and cap, appeared before the conspirators.

Voila 2! - Bennigsen exclaimed.

Despite a large number of participants in the murder, unified picture They didn’t describe what was happening in their memories. Their accounts of how Paul was killed differ greatly in detail. Who exactly said: “Sir, you are under arrest!” - Platon Zubov or Bennigsen? Who suggested not limiting ourselves to arrest, but immediately killing Pavel Petrovich? Who dealt that famous fatal blow to the emperor’s temple with a snuffbox? Who strangled him with a scarf and where did this scarf come from? Some claimed that one of the guardsmen took it from his neck (but the guards uniform did not allow the wearing of any frivolous scarves), others thought that the scarf was taken from the headboard of Pavel's bed (although the cot had no backrest, and a scarf is an inappropriate item in bedroom and generally in the wardrobe of the emperor, who did not recognize such excesses)... All reconstructions of the crime agree in general, but differ in small details. Probably, these details are not so important for the final outcome. Each of those who burst into the bedroom was ready to commit murder; it’s just that one of them turned out to be a hunter.

The conspirators were not themselves from horror and alcohol fumes and later simply could not reliably tell about what they experienced in a state of nervous frenzy; besides, everyone tried to portray themselves as nobly as possible in this drama... For example, Bennigsen recalled how some of the conspirators scared their comrades to death: “At that moment, other officers who had gotten lost in the chambers of the palace noisily entered the hallway; the noise they made frightened those who were in the bedroom with me. They thought that the guard was coming to the king’s aid, and they ran up the stairs to escape. I was left alone with the king and with my determination and sword I did not allow him to move. My fugitives meanwhile met with their allies and returned to Paul's room; There was a terrible crush, so that the screens fell on the lamp, which went out. I went out to fetch some fire from the other room; in this short period of time Paul passed away.”

There is so much in these few sentences - and panic fear conspirators, and their inability to come to an agreement at least with each other and behave with dignity, and Bennigsen’s desire at any cost to “wash off” the accusations of shed blood and at the same time emphasize his own important role in a revolution. After all, it was he and his sword, by his own admission, who did everything so that the matter would take the worst turn. So what difference does it make - whether he struck the emperor as one of the direct killers, and then fiercely trampled and kicked the dead body, or at that very moment he “came out to bring fire”? Count Palen, the recognized leader of the conspirators, deftly took measures to avoid being in Paul’s bedroom or nearby at the fatal moment, shifting responsibility to others. Initially, it was assumed that he, at the head of a battalion of guards, together with Count Uvarov 3, would penetrate the main staircase of the palace into the emperor’s chambers and join the killers. But Palen, as everyone noticed, marched too slowly, as if he was in no hurry. Uvarov had to constantly urge him on... And yet Palen and the guards came to the Mikhailovsky Castle too late to take personal part in the murder of the emperor. But just in time to reap the fruits of the coup...

As soon as it became clear that the plot was a success and Pavel Petrovich was no longer alive, Count Palen returned to the role of leader, again seizing the initiative. The other conspirators, tired and devastated after the murder, took it for granted at that moment. When they sobered up and pulled themselves together enough to analyze what had happened, some began to make claims of double-dealing against Palen. But it was too late, events continued to develop without their participation.

Von Pahlen's first brief order after the assassination read:

For family members and subjects: the sovereign has an apoplexy.

This version was announced to the people. St. Petersburg wits immediately made a “dark” joke that the sovereign died from an apoplectic blow to the temple with a snuffbox...

Grand Duke Alexander, who, according to the conspirators, was supposed to immediately assume power, after the death of his father, became confused and afraid. It’s one thing to talk abstractly about Pavel Petrovich’s abdication from the throne and remind, while saving face, that daddy needs to save his life in any case, and quite another thing to ascend to the throne by blood, stepping over the torn body of his own father... Alexander’s nerves gave way. He became hysterical, he seemed pitiful and weak.

But Palen was on his guard.

Stop being a boy! - he said sharply to Alexander. - Go reign!

Alexander obeyed. Count Palen did not yet know that the desire to turn the young king into an obedient puppet would never be forgiven him and he would soon have to pay for his intrigues. However, the price will not be too high for him.

On the fateful night, Alexander instructed Count Palen to inform the empress about the death of her husband. Palen transferred this responsibility to Chief Rankmaster Mukhanov. He, also wanting to evade the difficult mission, decided to involve the teacher of the royal daughters, Countess Lieven, in the case.

The unfortunate countess, awakened in the middle of the night, could not understand what they wanted from her, and then for a long time refused such an ambiguous assignment. But the courtiers forced the countess to go to the empress with mourning news. Maria Feodorovna, despite the proximity of her chambers to her husband’s bedroom, was so ignorant of what was happening that at first she thought that we were talking about the death of her eldest daughter Alexandra, who had been married off to Austria. But when the countess, carefully choosing her words, began to say that the emperor had fallen ill, he had a stroke and now he was completely ill, slowly approaching the essence of the matter, Maria Feodorovna understood everything and interrupted the court lady.

He died, he was killed! - she screamed.

Jumping out of bed, the empress rushed barefoot to her husband's room. Soldiers stood guard at the door with their bayonets crossed in front of her. She, the Russian Empress, was not allowed by ordinary grenadiers to see her husband’s body! This did not fit into Maria Feodorovna’s head. She screamed at the soldiers, demanded, cried, and finally fell to the floor and began hugging their knees, begging them to let them into Pavel’s bedroom. The soldiers themselves wiped away their tears, feeling sorry for the widow, but did not violate the order. One of the grenadiers brought her a glass of water to somehow calm her down.

These words hit the empress even more painfully. And the grenadier himself drank from the glass, showing that there was no poison in it, and again handed the glass to the empress...

She was taken away from the scene of the tragedy, and then the widow fell into a daze. She sat silently, motionless, “pale and cold, like a marble statue.” To hide the traces of the crime, Pavel’s body was “put in order” for almost thirty hours before Maria Feodorovna was allowed to say goodbye to her husband. It was not an easy test for the poor woman. Seeing the emperor’s face, she immediately realized how terrible Pavel Petrovich’s death was.

Those courtiers who had previously been critical of the empress now felt particularly dissatisfied with her behavior. Everything irritated them - and the fact that, having finally approached the deceased, she, still not over the shock, froze and did not shed a tear; and the fact that she then cried for too long and kissed his hands, and the fact that she cut off a lock of the emperor’s hair (probably to hide it in her medallion)... Those involved in the conspiracy did not like her courage, because she openly threatened the murderers with terrible punishments. Bennigsen, a man covered in criminal conspiracy from head to toe, led

himself with the Empress completely unceremoniously, throwing in her face in French: “Madame, they don’t play comedies here!”

The most terrible thing for Maria Fedorovna was the thought that her son, the heir to the throne, was involved in the death of his father. In the first days after the tragedy, she did not want to recognize Alexander as emperor and even casually noted that she herself would rule, at least until the issue of Alexander’s guilt in the death of his father was clarified (“Until he gives me an account of his behavior in this in fact” - this is how Bennigsen conveys her words). However, the empress did not insist on her own rights to the throne; she had four sons, each of whom could inherit the royal crown. It was important for Maria Feodorovna to know the truth. She was tormented by terrible and unfounded suspicions.

Congratulations, you are now the emperor! - she said to Alexander near the body of Pavel Petrovich. This was said in such a tone and was accompanied by such a look that Alexander fainted. The mother just looked at her defeated son and left the room without making any attempts to help him... Having woken up, Alexander hurried to his mother with tears in his eyes - to explain himself and beg for forgiveness.

A few days after Pavel’s death, another bitter news came from Austria - about the death of Alexandra Pavlovna. What the mother imagined in a nightmare on the night of the murder suddenly turned into a terrible reality. This almost finished off Maria Feodorovna. Helped her cope with heartache only support for daughter Maria. The Grand Duchess was sixteen years old, but after all the misfortunes that befell the imperial family, she immediately matured and literally did not leave her mother, taking care of her.

Maria Feodorovna's nephew, Prince Eugene of Württemberg, spoke about his cousin Maria: “She had a sympathetic and tender heart”... It is not surprising that Maria Feodorovna, who needed her daughter’s presence, did not want to let her go and delayed Maria’s wedding for a long time, although the agreement was marriage with one of the European princes was achieved by Pavel Petrovich. Only in the summer of 1804 did the Grand Duchess marry her fiancé, Karl Friedrich of Saxe-Weimar.

The daughters grew up and left one after another native home. Maria Fedorovna remained with her sons. Alexander was getting more and more used to his new role autocrat and felt more and more confident in it. The Empress loved her son very much and over time convinced herself of his complete innocence and non-involvement in the conspiracy against Paul. But before that, she took Alexander and Constantine to the chapel of St. Michael and there she made her sons swear in front of the icon that they knew nothing about the intention of the conspirators to take their father’s life. Alexander was hardly sincere in his oaths. But Konstantin, for all his frivolity and foolishness, truly grieved. He confessed to Sablukov: “After what happened, let my brother reign if he wants; but if the throne had gone to me, I would probably have renounced it.”

Konstantin kept his word. In 1825, he could have inherited the throne after his older brother, but abdicated. And the third brother, Nicholas, who was still an immature child at the time of the tragedy of 1801, became the Russian emperor.

_______________________________

1 Peter III was the son of a German duke and in Europe was considered not so much a representative of the Romanov dynasty as of the Holstein-Gottorp dynasty.

2 That's it! (French)

3 Count Fyodor Petrovich Uvarov in his youth participated in the suppression of the uprising in Warsaw; in 1794, at the age of twenty-one, he was promoted to adjutant general. Uvarov became one of the participants in the conspiracy, but did not play a significant role in the events. Subsequently he took part in Patriotic War 1812. In the Battle of Borodino, due to his own mistakes, he was unable to complete the command’s assignment and turned out to be one of the few generals who were not nominated for a reward for the battles at Borodino. His star, which shone brightly during the reign of Catherine and Paul, set.

Emperor Paul I did not have an attractive appearance: short stature, short snub nose... He knew about this and could, on occasion, joke about both his appearance and his entourage: “My ministers... oh, these gentlemen really wanted to lead me by the nose, but , unfortunately for them, I don’t have it!”

Paul I tried to establish a form of government that would eliminate the causes that gave rise to wars, riots and revolutions. But some of Catherine’s nobles, accustomed to debauchery and drunkenness, weakened the opportunity to realize this intention and did not allow it to develop and establish itself in time to change the life of the country on a solid basis. The chain of accidents is connected into a fatal pattern: Paul could not do this, and his followers no longer set this task as their goal.

F. Rokotov "Portrait of Paul I as a child"

S.S. Shchukin "Portrait of Emperor Paul I"

Pavel I Petrovich, Emperor of All Russia, was born on September 20, 1754 in the Summer Palace of Elizabeth Petrovna in St. Petersburg.

Childhood

Immediately after birth, he came under the full care of his grandmother, Elizaveta Petrovna, who took upon herself all the worries about his upbringing, effectively removing his mother. But Elizabeth was distinguished by her fickle character and soon lost interest in the heir, transferring him to the care of nannies who were only concerned that the child would not catch a cold, get hurt, or be naughty. In early childhood, a boy with a passionate imagination was intimidated by nannies: subsequently he was always afraid of the dark, flinched when there was a knock or an incomprehensible rustle, and believed in omens, fortune telling and dreams.

In the fifth year of his life, the boy began to be taught grammar and arithmetic, his first teacher F.D. Bekhteev used an original method for this: he wrote letters and numbers on wooden and tin soldiers and, lining them up in ranks, taught the heir to read and count.

Education

From 1760, Count N.I. became Paul’s main educator. Panin, who was his teacher before the heir’s marriage. Despite the fact that Pavel preferred military sciences, he received enough a good education: spoke French and German without difficulty, knew Slavic and Latin languages, read Horace in the original, and while reading, made extracts from the books. He had a rich library, a physics office with a collection of minerals, and a lathe for physical labor. He knew how to dance well, fencing, and was fond of horse riding.

O.A. Leonov "Paul I"

N.I. Panin, himself a passionate admirer of Frederick the Great, raised the heir in the spirit of admiration for everything Prussian at the expense of the national Russian. But, according to the testimony of contemporaries, in his youth Paul was capable, striving for knowledge, romantically inclined, with an open character, sincerely believing in the ideals of goodness and justice. After their mother's accession to the throne in 1762, their relationship was quite close. However, over time they worsened. Catherine was afraid of her son, who had more legal rights to the throne than herself. Rumors about his accession to the throne spread throughout the country; E. I. Pugachev appealed to him as a “son”. The Empress tried not to allow the Grand Duke to participate in discussions of state affairs, and he began to evaluate his mother’s policies more and more critically. Catherine simply “did not notice” her son’s coming of age, without marking it in any way.

Maturity

In 1773, Pavel married the Hesse-Darmstadt princess Wilhelmina (baptized Natalya Alekseevna). In this regard, his education was completed, and he was to be involved in government affairs. But Catherine did not consider this necessary.

In October 1766, Natalya Alekseevna, whom Pavel loved very much, died in childbirth with a baby, and Catherine insisted that Pavel marry a second time, which he did, going to Germany. Paul's second wife is the Württemberg princess Sophia-Dorothea-Augusta-Louise (baptized Maria Feodorovna). The encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron says this about the further position of Paul: “And after that, during the entire life of Catherine, the place occupied by Paul in government spheres was that of an observer, aware of his right to supreme management of affairs and deprived of the opportunity to use this right for changes in even the smallest details in the course of business. This situation was especially conducive to the development of a critical mood in Paul, which acquired a particularly sharp and bilious tone thanks to the personal element that entered him in a wide stream ... "

Russian coat of arms during the reign of Paul I

In 1782, Pavel Petrovich and Maria Fedorovna went on a trip abroad and were warmly received in European capitals. Pavel even received a reputation there as the “Russian Hamlet.” During the trip, Pavel openly criticized his mother’s policies, which she soon became aware of. Upon the return of the grand ducal couple to Russia, the Empress gave them Gatchina, where the “small court” moved and where Paul, who had inherited from his father a passion for everything military in the Prussian style, created his own small army, conducting endless maneuvers and parades. He languished in inactivity, made plans for his future reign and made repeated and unsuccessful attempts to engage in government activities: in 1774, he submitted a note to the Empress, drawn up under the influence of Panin and entitled “Discussion about the state regarding the defense of all borders.” Catherine assessed her as naive and disapproving of her policies. In 1787, Pavel asks his mother for permission to go as a volunteer to the Russian-Turkish war, but she refuses him under the pretext of Maria Feodorovna’s approaching birth. Finally, in 1788 he took part in Russian-Swedish war, but even here Catherine accused him of the fact that the Swedish Prince Charles was looking for rapprochement with him - and she recalled her son from the army. It is not surprising that gradually his character becomes suspicious, nervous, bilious and tyrannical. He retires to Gatchina, where he spends almost continuously for 13 years. The only thing that remains for him is to do what he loves: organizing and training “amusing” regiments, consisting of several hundred soldiers, according to the Prussian model.

Catherine hatched plans to remove him from the throne, citing his bad character and inability. She saw her grandson Alexander, son of Paul, on the throne. This intention was not destined to come true due to the sudden illness and death of Empress Catherine II in November 1796.

On the throne

The new emperor immediately tried to erase, as it were, everything that had been done during the 34 years of Catherine II’s reign, to destroy the order of Catherine’s reign that he hated - this became one of the most important motives of his policy. He also tried to suppress the influence of revolutionary France on the minds of Russians. His policy was developed in this direction.

First of all, he ordered the remains of Peter III, his father, who were buried in the Peter and Paul Fortress along with the coffin of Catherine II, to be removed from the crypt of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. On April 4, 1797, Paul was solemnly crowned in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. On the same day, several decrees were promulgated, the most important of which were: the “Law on Succession to the Throne,” which assumed the transfer of the throne according to the principle of pre-Petrine times, and the “Institution on the Imperial Family,” which determined the order of maintenance of persons of the reigning house.

The reign of Paul I lasted 4 years and 4 months. It was somewhat chaotic and contradictory. He's been kept on a leash for too long. And so the leash was removed... He tried to correct the shortcomings of the former regime that he hated, but he did it inconsistently: he restored the Peter's colleges liquidated by Catherine II, limited local self-government, issued a number of laws leading to the destruction of noble privileges... They could not forgive him for this.

In the decrees of 1797, landowners were recommended to perform a 3-day corvee, it was forbidden to use peasant labor on Sundays, it was not allowed to sell peasants under the hammer, and Little Russians were not allowed to sell them without land. The nobles who were fictitiously enrolled in them were ordered to report to the regiments. Since 1798, noble societies became under the control of governors, and nobles again began to be subjected to corporal punishment for criminal offenses. But at the same time, the situation of the peasants was not alleviated.

Transformations in the army began with the replacement of “peasant” uniforms with new ones, copied from Prussian ones. Wanting to improve discipline among the troops, Paul I was present every day at exercises and training sessions and severely punished the slightest mistakes.

Paul I was very afraid of the penetration of the ideas of the Great French Revolution to Russia and introduced some restrictive measures: already in 1797, private printing houses were closed, strict censorship was introduced for books, a ban was imposed on French fashion, and the travel of young people to study abroad was prohibited.

V. Borovikovsky "Paul I in the uniform of Colonel of the Preobrazhensky Regiment"

Upon ascending the throne, Paul, in order to emphasize the contrast with his mother, declared peace and non-interference in European affairs. However, when in 1798 there was a threat of Napoleon re-establishing an independent Polish state, Russia took an active part in organizing the anti-French coalition. In the same year, Paul assumed the duties of Master of the Order of Malta, thus challenging the French emperor who had captured Malta. In this regard, the Maltese octagonal cross was included in the state coat of arms. In 1798-1800, Russian troops successfully fought in Italy, and the Russian fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, which caused concern on the part of Austria and England. Relations with these countries completely deteriorated in the spring of 1800. At the same time, rapprochement with France began, and a plan for a joint campaign against India was even discussed. Without waiting for the corresponding agreement to be signed, Pavel ordered the Don Cossacks, who were already stopped by Alexander I, to set out on a campaign.

V.L. Borovikovsky "Portrait of Paul I in the crown, dalmatic and insignia of the Order of Malta"

Despite the solemn promise to maintain peaceful relations with other states, given upon accession to the throne, he took an active part in the coalition with England, Austria, the Kingdom of Naples and Turkey against France. The Russian squadron under the leadership of F. Ushakov was sent to the Mediterranean Sea, where, together with the Turkish squadron, it liberated the Ionian Islands from the French. In Northern Italy and Switzerland, Russian troops under the command of A.V. Suvorov won a number of brilliant victories.

The last palace coup of the passing era

Mikhailovsky Castle in St. Petersburg, where Paul I was killed

The main reasons for the coup and death of Paul I were the infringement of the interests of the nobility and the unpredictability of the emperor’s actions. Sometimes he exiled or sent people to prison for the slightest offense.

He planned to declare Maria Feodorovna’s 13-year-old nephew heir to the throne, adopting him, and imprison his eldest sons, Alexander and Konstantin, in the fortress. In March 1801, a ban on trade with the British was issued, which threatened to damage the landowners.

The fate of this emperor was tragic. He was raised without parents (from birth he was taken away from his mother, the future empress, and was raised by nannies. At the age of eight, he lost his father, Peter III, who was killed in a coup d'etat) in an atmosphere of neglect from his mother, as an outcast, forcefully removed from power . Under these conditions, suspicion and temper arose in him, combined with brilliant abilities in science and languages, with innate ideas about knightly honor and state order. The ability for independent thinking, close observation of the life of the court, the bitter role of an outcast - all this turned Paul away from the lifestyle and policies of Catherine II. Still hoping to play some role in state affairs, Pavel, at the age of 20, submitted to his mother a draft military doctrine of a defensive nature and concentration of state efforts on internal problems. She was not taken into account. He was forced to try out military regulations on the Gatchina estate, where Catherine moved him out of sight. There, Paul's conviction about the benefits of the Prussian order was formed, which he had the opportunity to become acquainted with at the court of Frederick the Great - king, commander, writer and musician. The Gatchina experiments later became the basis of the reform, which did not stop even after the death of Paul, creating an army of a new era - disciplined and well-trained.

The reign of Paul I is often spoken of as a time of forced discipline, drill, despotism, and arbitrariness. There is, however, an alternative point of view according to which the “Russian Hamlet” Pavel fought against laxity in the army and in general in the life of Russia at that time and wanted to make public service the highest valor, stop embezzlement and negligence and thereby save Russia from the collapse that threatened it.

Many anecdotes about Paul I were spread in those days by the nobles, whom Paul I did not allow to live a free life, demanding that they serve the Fatherland.

Succession reform

The decree on succession to the throne was issued by Paul I on April 5, 1797. With the introduction of this decree, the uncertainty of the situation in which the Russian imperial throne found itself with every change of reign and with constant coups and seizures of supreme power after Peter I as a result of his legislation ended. Love for the rule of law was one of the striking features in the character of Tsarevich Paul at that time of his life. Smart, thoughtful, impressionable, as some biographers describe him, Tsarevich Paul showed an example of absolute loyalty to the culprit of his removal from life - until the age of 43, he was under undeserved suspicion on the part of the Empress-Mother for attempts on the power that rightfully belonged to him more than herself, who ascended the throne at the cost of the lives of two emperors (Ivan Antonovich and Peter III). A feeling of disgust for coups d'état and a sense of legitimacy were one of the main incentives that prompted him to reform the succession to the throne, which he considered and decided on almost 10 years before its implementation. Paul canceled Peter's decree on the appointment by the emperor himself of his successor to the throne and established a clear system of succession to the throne. From that moment on, the throne was inherited in the male line, after the death of the emperor it passed to the eldest son and his male offspring, and if there were no sons, to the next oldest brother of the emperor and his male offspring, in the same order. A woman could occupy the throne and pass it on to her offspring only if the male line was terminated. With this decree, Paul excluded palace coups, when emperors were overthrown and erected by the force of the guard, the reason for which was the lack of a clear system of succession to the throne (which, however, did not prevent palace coup

March 12, 1801, during which he himself was killed). Paul restored the system of collegiums, and attempts were made to stabilize the financial situation of the country (including the famous action of melting down palace services into coins).

Postage stamp "Paul I signs the Manifesto on the three-day corvee"

Prerequisites Corvée economy of the Russian Empire second century was the most intensive form of exploitation of peasant labor and, in contrast to the quitrent system, led to extreme enslavement and maximum exploitation of the peasants. The growth of corvée duties gradually led to the emergence of mesyachina (daily corvee labor), and small peasant farming faced the threat of extinction. Serf peasants were not legally protected from arbitrary exploitation by landowners and the aggravations of serfdom, which took forms close to slavery.

During the reign of Catherine II, the problem of legislative regulation of peasant duties became the subject of public discussion in an atmosphere of relative openness. New projects for the regulation of peasant duties are appearing in the country, and heated discussions are unfolding. The activities of the Free Economic Society and the Statutory Commission, created by Catherine II, played a key role in these events. Attempts to legislatively regulate peasant duties were initially doomed to failure due to the harsh opposition of the noble-landowner circles and the political elite associated with them, as well as due to the lack of real support for reform initiatives from the autocracy.

Paul I, even before his accession, took real measures to improve the situation of peasants on his personal estates in Gatchina and Pavlovsk. Thus, he reduced and reduced peasant duties (in particular, a two-day corvee existed on his estates for a number of years), allowed peasants to go to fishing in their free time from corvée work, issued loans to peasants, built new roads in villages, opened two free medical hospitals for his peasants, built several free schools and schools for peasant children (including for disabled children), as well as several new churches. He insisted on the need for legislative regulation of the situation of serfs. "Human,- wrote Pavel, - the first treasure of the state”, “saving the state is saving the people”(“Discourse on the State”). Not being a supporter of radical reforms in the field peasant question, Paul I allowed for the possibility of some limitation of serfdom and suppression of its abuses.

Manifesto

BY GOD'S GRACE

WE ARE PAUL THE FIRST

Emperor and Autocrat

ALL-RUSSIAN,

and so on, and so on, and so on.

We announce to all OUR loyal subjects.

The Law of God taught to US in the Decalogue teaches US to devote the seventh day to it; why on this day glorified by the triumph of the Christian faith, and on which WE were honored to receive the sacred anointing of the world and the Royal wedding on OUR Ancestor Throne, we consider it our duty to the Creator and the giver of all good things to confirm throughout OUR Empire about the exact and indispensable fulfillment of this law, commanding everyone and everyone should observe that no one under any circumstances dares to force the peasants to work on Sundays, especially since for rural products the six days remaining in the week, an equal number of them, are generally shared, both for the peasants themselves and for their work for the benefit of the following landowners, with good management they will be sufficient to satisfy all economic needs. Given in Moscow on the day of Holy Easter, April 5, 1797.

Assessment of the Manifesto by contemporaries

Representatives of foreign powers saw in him the beginning of peasant reforms.

The Decembrists sincerely praised Paul for the Manifesto on the Three-Day Corvee, noting the sovereign’s desire for justice.

The Manifesto was met with muted murmurs and widespread boycott by conservative noble-landowner circles, who considered it an unnecessary and harmful law.

The peasant masses saw hope in the Manifesto. They regarded it as a law that officially protected their interests and alleviated their plight, and tried to complain about the boycott of its norms by the landowners.

But the implementation of the norms and ideas of the Manifesto on the three-day corvee, issued by Emperor Paul I, was initially doomed to failure. The ambiguity of the wording of this law and the undeveloped mechanisms for its implementation predetermined the polarization of opinions of government and judicial officials of the country regarding the interpretation of its meaning and content and led to a complete lack of coordination in the actions of the central, provincial and local structures that controlled the implementation of this law. The desire of Paul I to improve the difficult situation of the peasant masses was combined with his stubborn reluctance to see in the serf peasantry an independent political force and social support for the anti-serfdom initiatives of the autocracy. The indecisiveness of the autocracy led to the lack of strict control over compliance with the norms and ideas of the Manifesto and the connivance of its violations.

Military reform of Paul I

G. Sergeev " Military exercise on the parade ground in front of the palace" (watercolor)

- Single soldier training has been introduced and content has been improved.

- A defense strategy has been developed.

- 4 armies have been formed in the main strategic directions.

- Military districts and inspections were created.

- New statutes have been introduced.

- Reform of the guard, cavalry and artillery was carried out.

- The rights and obligations of military personnel are regulated.

- Generals' privileges have been reduced.

Reforms in the army caused dissatisfaction on the part of the generals and the guard. The guardsmen were required to serve as expected. All officers assigned to the regiments were required to report to duty from long-term leave; some of them and those who did not appear were expelled. Unit commanders were limited in their disposal of the treasury and the use of soldiers in household work.

The military reform of Paul I created the army that defeated Napoleon.

Anecdotes about Paul were inflated in political purposes. The indignant nobility did not understand that Paul, by “tightening the screws,” extended the reign of the “service class” for a hundred years.

Paul's contemporaries adapted to him. He established order and discipline, and this met with approval in society. True military men quickly realized that Pavel was hot-tempered, but easy-going and understood humor. There is a known case that allegedly Paul I sent an entire regiment from a watch parade to Siberia; in fact, Pavel showed his dissatisfaction in a sharp form, reprimanding the commander in front of the formation. In irritation, he said that the regiment was worthless and that it should be sent to Siberia. Suddenly the regiment commander turns to the regiment and gives the command: “Regiment, march to Siberia!” Here Pavel was taken aback. And the regiment marched past him. Of course, they caught up with the regiment and turned back. And the commander had nothing. The commander knew that Pavel would eventually like such a prank.

Dissatisfaction with Paul was demonstrated primarily by part of the higher nobility, which fell out of favor under Paul for various reasons: either because they constituted the “Catherine’s court” hated by the emperor, or were held accountable for embezzlement and other offenses.

F. Shubin "Portrait of Paul I"

Other reforms

One of the first attempts to create a code of laws was made. All subsequent rulers of Russia up to the present time have tried to create a code similar to the “Napoleonic Code” in France. No one succeeded. Bureaucracy got in the way. Although the bureaucracy was “trained” under Paul, this training only made it stronger.

* Decrees were declared not to be considered laws. During the 4 years of the reign of Paul I, 2179 decrees were issued (42 decrees per month).* The principle was proclaimed: “Revenues are for the state, not for the sovereign.” Audits carried out government agencies and services. Significant sums were recovered in favor of the state.

* The issue of paper money was stopped (by this time the first paper ruble was worth 66 kopecks in silver).

* Emphasis was placed on the distribution of lands and peasants into private hands (during the reign - 4 years), 600 thousand souls were granted, over 34 years Catherine II granted 850 thousand souls. Pavel believed that landowners would support the peasants better than the state.

* The “Borrow Bank” was established and the “bankruptcy charter” was adopted.

* The family of Academician M. Lomonosov was exempted from the capitation salary.

* Polish rebels led by T. Kosciuszko were released from prison.On the night of March 11-12, 1801, Pavel I Petrovich was killed by conspiratorial officers in the newly built Mikhailovsky Castle: the conspirators, mostly guards officers, burst into the bedroom of Paul I demanding that he abdicate the throne. When the emperor tried to object and even hit one of them, one of the rebels began to strangle him with his scarf, and the other hit him in the temple with a massive snuff box. It was announced to the people that Paul I had died of apoplexy.

Paul I and Maria Feodorovna had 10 children:

During his reign, Paul the First did not execute anyone

Historical science has never known such a large-scale falsification as the assessment of the personality and activities of the Russian Emperor Paul the First. After all, what about Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Stalin, around whom polemical spears are now mostly breaking! No matter how you argue, “objectively” or “biasedly” they killed their enemies, they still killed them. And Paul the First did not execute anyone during his reign.

He ruled more humanely than his mother Catherine the Second, especially in relation to ordinary people. Why is he a “crowned villain,” in Pushkin’s words? Because, without hesitation, he fired negligent bosses and even sent them to St. Petersburg (about 400 people in total)? Yes, many of us now dream of such a “crazy ruler”! Or why is he actually “crazy”? Yeltsin, excuse me, sent some needs in public, and he was considered simply an ill-mannered “original.”

Not a single decree or law of Paul the First contains any signs of madness; on the contrary, they are distinguished by reasonableness and clarity. For example, they put an end to the madness that was happening with the rules of succession to the throne after Peter the Great.

The 45-volume “Complete Code of Laws of the Russian Empire,” published in 1830, contains 2,248 documents from the Pauline period (two and a half volumes) - and this despite the fact that Paul reigned for only 1,582 days! Therefore, he issued 1-2 laws every day, and these were not grotesque reports about “Second Lieutenant Kizha,” but serious acts that were later included in the “Complete Code of Laws”! So much for “crazy”!