Musa Jalil is a Tatar poet who sang of freedom and courage. He passionately loved life and his homeland, and fought for his ideals until his last breath. However, Musa Jalil’s feat became known decades after his tragic death. On the 75th anniversary of the poet’s death, let us remember the fate of the lyricist and philosopher.

Musa Jalil: biography

« By his death he proved to the Creator: the Word is not a ghost in the desert“- this is how Igor Sulga succinctly but accurately described the fate of the author of the “Moabit Notebook”.

Musa Jalil, whose biography was presented in a distorted form for a long time, belongs to the cohort of Soviet writers whose names and works were in oblivion. The reason for this is the accusation of betrayal of the Motherland and collaboration with the Nazis. Miraculously, the truth about the feat of the courageous poet was discovered. Let us tell you in more detail about the details of life and death, creativity and fame, which belatedly came to the hero:

Childhood and revolutionary youth

The biography of Musa Jalil is a striking example of the majority of Soviet writers whose talent was discovered thanks to social changes after 1917. Jalil is the son of the Zalilov peasants who lived in the village of Mustafino, where the poet who glorified the Tatar people was born in 1906. Rakhima, the poet's mother, came from the family of a confessor - a mullah, so she saw her son as a minister of worship in the future.

When in search better life The family moved to Orenburg, the boy was sent to a madrasah. The school in which Musa Jalil received his spiritual education provided not only theological, but also secular education. Since childhood, Musa had a keen sense of the word: his grandmother's fairy tales, his mother's songs, the sonorous Tatar language and the humanitarian education received at the theological school bore fruit - Musa wrote his first poems.

The revolution and the construction of a new society radically changed the fate of Musa Jalil. He becomes a student at the workers' faculty, receives a technical profession, joins the Komsomol, and later returns to his small homeland, where he puts the ideals of the revolution into practice.

Kazan period of Musa Jalil's life

Musa Mustafovich Zalilov is a 21-year-old student at Moscow State University. He chooses the literary department, enjoys love and respect among his classmates, and becomes famous thanks to his creative successes: his works in Tatar are published in leading central newspapers and magazines. After studying, Jalil works as a journalist in the editorial offices of periodicals.

At the age of 29, the poet heads the literary department of the Kazan Opera Theater. Thanks to him, translations into Tatar of Russian classic writers, reviews, art criticism and literary articles appear. In the late 1930s, Musa Jalil headed the Tatar branch of the Writers' Union.

Anti-fascist disguised as a member of Idel-Ural

The Tatar writer turned thirty-five when the Second World War broke out. world war. Despite the release from conscription, he goes to the front in the first ranks of volunteers.

At first he was assigned to horse reconnaissance, but when the command learned that Jalil was a writer, he was sent as a war correspondent and political instructor to the Second Shock Army. A year later, the poet was seriously wounded, followed by captivity and a concentration camp.

Next, Jalil’s biography takes a sharp turn: he joins the ranks of “Idel-Ural” - the German legion. When the 1941 Blitzkrieg was defeated by the Nazis, and the Soviet Union offered fierce resistance, it became clear that the war would drag on. The Nazis decided to undermine unity Soviet people by placing a bet on national interests. They attracted highly educated people of various nationalities, including Tatars, to cooperate.

“Idel-Ural” is a union of representatives of the peoples of the Volga region, whose activities were directed by the Nazis. The legion's task is to educate ardent ideological opponents of Soviet power, who could later carry out ideological subversion among their fellow tribesmen.

The Nazis equipped those who agreed to cooperate, provided them with food and medical care, and freed them from hard work. The prisoners at the council decided to boycott this proposal, but the majority agreed to take advantage of the opportunities that participation in Idel-Ural provided to prepare an uprising against the Nazis. Musa Jalil is one of the ideological inspirers of the resistance.

Musa, under the guise of an educational mission, traveled to the camps, but did not propagate Nazi ideas, but organized escapes and prepared an uprising. Jalil organized the underground for a whole year, but the plan of courageous people was revealed a few days before the start of the uprising. Musa Jalil was arrested in 1943 and sent to Moabit prison, and in 1944, on August 25, he was executed by guillotine.

According to the prisoners of war who were sitting with Musa, the only thing that worried the poet while awaiting the verdict was that in his homeland he would be considered a traitor. Therefore, he tried to express the essence of his action in poetry written during this period.

In 1953, through the efforts of Konstantin Simonov, into whose hands the poems of Musa Jalil, written in Gestapo dungeons, fell, the poet was rehabilitated. Four years later, for his accomplished feat, he was posthumously awarded a Hero Soviet Union, and his works are returned to the Tatar people.

Musa Jalil: personal life

The portrait of Musa Jalil says a lot about his character and temperament. Brave, energetic, open man, radiating love of life and charisma. These qualities attracted women to him.

It is known that the famous poet of Tatarstan was married three times, but little is known about his wives, more information about the children of the famous poet:

Albert

In his first marriage with Rauza Khanum, a boy, Albert, was born. He became a career military man: he dreamed of becoming a pilot, but due to an eye disease he did not pass the medical examination, but he entered the Saratov Military School.

After graduation he served in the Caucasus. In 1976, he wrote a report with a request to be sent to serve in Germany, where he spent twelve years. Thanks to Albert, memories of a group of underground anti-fascists led by Kurmashev, which included Musa Jalil, were made public.

The most expensive thing that reminded Albert of his famous father was the first collection of poems with an autograph. Jalil published it when his son was only three months old.

Lucia

Lucia was born in a civil marriage with Zakiya Sadykova. She was born in 1936, when Musa Jalil lived and worked in Kazan. Soon the parents separated, and the girl and her mother moved to Tashkent.

Lucia had an excellent ear for music, so after school she received a music education. She taught for some time at one of the Kazan schools, then moved to Moscow, where she studied to become a director.

Lucia dreamed of making a film about her father, and she was lucky enough to do it: in 1968, she took part in the filming of “The Moabit Notebook” as an assistant director.

Chulpan

The third marriage with Amina Khanum gave Musa Jalil a daughter, Chulpan. She was born in 1937 in Kazan. The last time the girl saw her father was in 1942, when he was sent to the front.

For many years, the only memory of my father was his poetry. Musa Jalil dedicated the poem “To my daughter Chulpan” to his daughter, in which he foresaw his death and, saying goodbye, revealed to her the depth of his fatherly love.

It is known that the daughter of the famous Tatar poet worked as an editor at the publishing house " Fiction", lived in Moscow. She has a daughter, Tatyana. She became a pianist. Two grandchildren, Mikhail and Lisa, also chose the same field. Chulpan Museevna believes that the poet’s great-grandchildren passed on his musical abilities: He taught himself to play the piano and mandolin.

Musa Jalil, whose poems became the only source of information about his fate and experiences during his stay in Nazi dungeons, became a symbol of perseverance and courage, loyalty to his word and desperately tender love for children, whose development he was not destined to see.

Musa Jalil: poems

Musa Jalil's poems amaze with their sincerity and emotionality. Whatever the poet wrote about, he did it with passion and conviction:

Early lyrics

Jalil's early works are dedicated to the revolution, the formation of Soviet power, and the changes that took place in the state. Critics argue that the propaganda focus and maximalism that are characteristic of the poetry “Comrades”, “We are going”, etc., were a manifestation of the character and beliefs of Musa Jalil.

These works implement the oriental style of versification, which is characterized by expressiveness, metaphor and pathos. Such features are inherent in poems published in collections of the early 1930s. - “Order-bearing millions”, “Poems and poems”.

Folklore motives

Having become the literary editor of the opera house in Kazan, Musa Jalil turned to folk epic in search of themes and plots for new works. He rethought the history of the epic “Jik Mergen”, tales and traditions of Tatar folklore. Their plot twists and turns under the pen of Musa gave life to the libretto of the opera “Golden Haired”. The premiere took place in early June 1941, a few weeks before the start of the war.

War lyrics

The most striking and highly artistic works written by the Tatar poet are military lyrics. Musa Jalil, whose poems about war penetrate to the core, reveal the cruel reality of war. Every line of the poem “Barbarism” is permeated with pain.

The poem “Letter from the Trench,” addressed to Ghazi’s friend Kashshaf, reveals another side of the war - motives Soviet soldiers who kill the enemy to protect their land, children, wives, mothers and fathers. This noble goal strengthens the spirit of warriors, awakens in them the strength of the ancient batyrs, who centuries ago also defended their lands from aggressors.

In the front-line trenches, the value of simple human feelings and relationships is revealed: friendship, mutual understanding, unity and mutual assistance. “Without a leg”, “Tear” - lyrical works, in which the unbending spirit of the defenders of the Fatherland, the loyalty and devotion of their wives and loved ones are glorified. Jalil sang the spirit of freedom and hope for victory in his works “Oak” and “Forest”.

"Moabite Notebook"

In Hitler's dungeons, Musa Jalil wrote more than a hundred texts: the author himself indicated that he wrote 125 poems and a poem, but 115 have reached us. Two notebooks are known in which the lyrics of the Tatar poet from the period of captivity are collected. They were preserved by Jalil's cellmates. Two more notebooks were lost after the war.

In the Moabit and Plötzensee prisons, creativity became the only way for the poet to strengthen his spirit and not break during interrogations, where cruel torture was used. Among the poems of this period are reflections on the cruelty of people and the generosity of animals (“Wolves”), on the fact that the human soul will always be free (“Dream”, “Will”), on loyalty and betrayal (“Forgive me, Motherland!”, “ Don’t believe it!”), about the inflexibility of the spirit (“The Power of the Horseman”), etc.

The strength of will and thirst for life is evidenced by the humorous miniatures that saved Musa Jalil and his comrades from despondency and fear of death: “The Ring”, “Cold Love”, “The Lover and the Cow”, “The Flea”, etc.

Musa Jalil wrote on scraps of paper, between the lines in prayer books. He knew that he was destined to die, but he wanted freedom for his works. It was they who told the truth about the courageous poet, loving father and soldier devoted to the Motherland.

Musa Jalil - Tatar Soviet poet, Hero of the Soviet Union (1956), Lenin Prize laureate (posthumously, 1957).

Musa Jalil (Musa Mustafovich Zalilov)

(1906-1944)

The purpose of life is this: to live in such a way that even after death you do not die.

Jalil (Dzhalilov) Musa Mustafovich (real name Musa Mustafovich Zalilov) was born on February 15, 1906, the village of Mustafino, now the Orenburg region, the sixth child in the family. Father - Mustafa Zalilov, mother - Rakhima Zalilova (nee Sayfullina). The biography of Jalil Musa in early childhood was closely connected with his native village and was very similar to the life of many of his friends - ordinary village boys: he swam in the Net River, herded geese, loved to listen to Tatar songs that his mother sang to him, and fairy tales that she composed Grandmother Gilmi for her beloved grandson.

When the family moved to the city, Musa began going to the Orenburg Muslim theological school-madrassa "Khusainiya", which after October Revolution was transformed into the Tatar Institute of Public Education - TINO.

His first poems were published in the newspaper "Kyzyl Yoldyz" ("Red Star") when he was 13 years old. Gradually, the debut and in many ways naive works of the young author become more and more mature, acquire depth, take shape, and in 1925 his first collection of poems, “We Are Walking,” was published. This period in early poetry the author is called by many “red”, constant ebullient and active participation in public life comes into his poetry with images of the crimson banner and the scarlet dawn of freedom (“Red Army”, “Red Power”, “Red Holiday”).

In 1927, Musa Jalil moved to Moscow, where he worked as an editor for children's magazines and entered the literary department of Moscow State University.

After graduating from Moscow State University, Jalil was appointed head of the literature and art department of the Tatar newspaper Kommunist in Moscow.

Collections of poems from the period 1929-1935 - “To a Comrade”, “Ordered Millions”, “Poems and Poems”.

In 1935, Musa Jalil was appointed head of the literary part of the Tatar studio at the Moscow State Conservatory. P.I. Tchaikovsky. The studio was supposed to train national personnel to create the first opera house in Kazan. Jalil wrote the libretto for the operas "Altynchech" ("Golden-Haired") and "Fisherman Girl". In December 1938, the opera house was opened. Musa became the first head of the literary department of the Tatar Opera House. Nowadays the Tatar State Opera and Ballet Theater is named after Musa Jalil. Jalil worked at the theater until July 1941, i.e. before he was drafted into the Red Army. In 1939, Jalil was elected Chairman of the Board of the Union of Writers of Tatarstan.

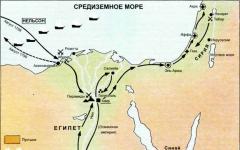

In 1941 he was drafted into the Red Army. He fought on the Leningrad and Volkhov fronts, and was a correspondent for the newspaper “Courage”.

In June 1942, during the Lyuban operation Soviet troops was seriously wounded, captured, and imprisoned in Spandau prison. In the concentration camp, Musa, who called himself Gumerov, joined the Wehrmacht unit - the Idel-Ural legion, which the Germans intended to send to Eastern Front. In Jedlino (Poland), where the Idel-Ural legion was training, Musa organized an underground group among the legionnaires and arranged escapes for prisoners of war. The first battalion of the Volga-Tatar Legion rebelled and joined the Belarusian partisans in February 1943. For participation in an underground organization, Musa was executed by guillotine on August 25, 1944 in the Plötzensee military prison in Berlin.

In 1946, the USSR MGB opened a search case against Musa Jalil. He was accused of treason and aiding the enemy. In April 1947, the name of Musa Jalil was included in the list of especially dangerous criminals.

Much has been written about the horrors of fascist captivity. Almost every year new books, plays, films appear on this topic... But no one will tell about it the way the prisoners themselves did concentration camps and prisons, witnesses and victims of the bloody tragedy. Their testimony contains something more than the harsh certainty of fact. They contain great human truth, for which they paid at the cost of their own lives.

One of such unique documents, scorching with its authenticity, is Jalil’s “Moabit Notebooks”. They contain few everyday details, almost no descriptions of prison cells, ordeals and cruel humiliations to which the prisoners were subjected. These poems have a different kind of concreteness - emotional, psychological. A cycle of poems written in captivity, namely the notebook that played main role in the “discovery” of the poetic feat of Musa Jalil and his comrades, was preserved by the participant anti-fascist resistance, Belgian Andre Timmermans, who shared a cell with Jalil in Moabit prison. In their last meeting Musa said that he and a group of his Tatar comrades would soon be executed, and gave the notebook to Timmermans, asking him to transfer it to his homeland.

After the end of the war and his release from prison, Andre Timmermans took the notebook to the Soviet embassy. Later, the notebook fell into the hands of the poet Konstantin Simonov, who organized the translation of Jalil’s poems into Russian, removed the slanderous slander against the poet and proved the patriotic activities of his underground group. An article by K. Simonov about Musa Jalil was published in one of the central newspapers in 1953, after which the triumphant “procession” of the feat of the poet and his comrades into the national consciousness began.

I will not bend my knees, executioner, before you,

Although I am your prisoner, I am a slave in your prison.

When my time comes, I will die. But know this: I will die standing,

Although you will cut off my head, villain.

Alas, not a thousand, but only a hundred in battle

I was able to destroy such executioners.

For this, when I return, I will ask for forgiveness,

I bowed my knees at my homeland.

Did you know that

In May 1945, one of the units of the Soviet troops that stormed Berlin burst into the courtyard of the fascist Moabit prison. There was no one there anymore - neither guards nor prisoners. The wind carried scraps of papers and garbage across the empty yard. One of the fighters drew attention to a piece of paper with familiar Russian letters. He picked it up, smoothed it out (it turned out to be a page torn from some German book) and read the following lines: “I, the famous Tatar writer Musa Jalil, am imprisoned in the Moabit prison as a prisoner facing political charges, and, probably, I will soon shot. If any of the Russians get this recording, let them convey greetings from me to my fellow writers in Moscow.” Then there was a list of the names of the writers to whom the poet sent his last greetings, and the address of the family.

This is how the first news about the feat of the Tatar patriotic poet came home. Soon after the end of the war, the poet’s songs also returned in a roundabout way, through France and Belgium - two small homemade notebooks containing about a hundred poems. These poems have become world famous today.

In February 1956, for the exceptional tenacity and courage shown in the fight against the Nazi invaders, senior political instructor Musa Jalil was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. And in 1957, for the cycle of poems “The Moabit Notebook”, he was the first among poets to be awarded the Lenin Prize.

He wrote 4 librettos for the operas “Altyn Chech” (“Golden-haired”, 1941, music by composer N. Zhiganov) and “Ildar” (1941).

In the concentration camp, Jalil continued to write poetry, in total he wrote at least 125 poems, which after the war were transferred to his homeland by his cellmate.

The Tatar State Opera and Ballet Theater, whose literary studio he headed, and one of the central streets of the city bear the name of Musa Jalil.

Musa Jalil's apartment museum is located in the poet's apartment, where he lived in 1940-1941. There is a unique exhibition here, which consists of the poet’s personal belongings, photographs and interior items.

Monument to the Tatar poet, Hero of the Soviet Union, Lenin Prize laureate Musa Jalil in Kazan

Internet resources:

Musa Jalil. Poetry/ M. Jalil // Poems of classical and modern authors. – Access mode: http://stroki.net/content/blogcategory/48/56

Musa Jalil. Moabit notebook/ M. Jalil // Young Guard. – Access mode: http://web.archive.org/web/20060406214741/http://molodguard.narod.ru/heroes20.htm

Musa Jalil. Poetry/ M. Jalil // National Library of the Republic of Tatarstan. – Access mode: http://kitaphane.tatarstan.ru/jal_3.htm

Musa Jalil. Favorites/ M. Jalil // Library of Maxim Moshkov. – Access mode: http://lib.ru/POEZIQ/DZHALIL/izbrannoe.txt_with-big-pictures.html

Aphorisms and quotes:

If life passes without a trace,

In lowliness, in captivity, what kind of honor is this?

There is beauty only in freedom of life!

Only in a brave heart there is eternity!

...Our life is just a spark of the whole life of the Motherland.

Be bold in right deeds, modest in words.

It is useless to live - it is better not to live.

Live in such a way that you don’t die even after death.

We will forever glorify that woman whose name is Mother.

It’s not scary to know that death is coming to you, If you die for your people.

Shine on our descendants like a beacon, Shine like a person, not a firefly.

Is it possible to hide old age?

You know, honey, no matter how you dance -

No oven could do it

Ice to melt frozen souls.

It doesn’t matter what you are, you’re out of sight

The essence would be bright.

Be human to the end.

Be with a high heart

Heart with the last breath of life

He will fulfill his firm oath:

I always dedicated songs to my fatherland,

Now I give my life to my fatherland.

I have often met elephant people,

I marveled at their monstrous bodies,

But I recognized him as a person

Only a man according to his deeds.

Recognition at the state level overtook Musa Jalil after his death. The poet, accused of treason, was given what he deserved thanks to the caring fans of his lyrics. Over time, the turn came for prizes and the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. But the real monument to the unbroken patriot, in addition to the return of his good name, was the unquenchable interest in creative heritage. As the years pass, words about the Motherland, about friends, about love remain relevant.

Childhood and youth

The pride of the Tatar people, Musa Jalil, was born in February 1906. Rakhima and Mustafa Zalilov raised 6 children. The family lived in Orenburg village, in search of a better life, she moved to the provincial center. There, the mother, being the daughter of a mullah herself, took Musa to the Muslim theological school-madrassa “Khusainiya”. Under Soviet rule, the Tatar Institute of Public Education grew out of a religious institution.

The love of poetry and the desire to express thoughts beautifully were passed on to Jalil with folk songs sung by his mother and fairy tales that his grandmother read at night. At school, in addition to theological subjects, the boy excelled in secular literature, singing and drawing. However, religion did not interest the guy - Musa later received a certificate as a technician at the workers' faculty at the Pedagogical Institute.

As a teenager, Musa joined the ranks of Komsomol members and enthusiastically campaigned for children to join the ranks of the pioneer organization. The first patriotic poems became one of the means of persuasion. In Mustafino's native village, the poet created a Komsomol cell, whose members fought the enemies of the revolution. Activist Zalilov was elected to the Bureau of the Tatar-Bashkir section of the Komsomol Central Committee as a delegate to the All-Union Komsomol Congress.

In 1927, Musa entered Moscow State University, the literary department of the ethnological faculty (future philological department). According to the recollections of his dorm roommate Varlam Shalamov, Jalil received preferences and love from others at the university due to his nationality. Not only is Musa a heroic Komsomol member, but he is also a Tatar, studying at a Russian university, writes good poetry, and reads them excellently in his native language.

In Moscow, Jalil worked in the editorial offices of Tatar newspapers and magazines, and in 1935 he accepted an invitation from the newly opened Kazan Opera Theater to head its literary department. In Kazan, the poet plunged headlong into his work, selected actors, wrote articles, librettos, and reviews. In addition, he translated works of Russian classics into Tatar. Musa becomes a deputy of the city council and chairman of the Writers' Union of Tatarstan.

Literature

The young poet’s first poems began to be published in the local newspaper. Before the Great Patriotic War 10 collections were published. The first “We Are Coming” - in 1925 in Kazan, 4 years later - another one, “Comrades”. Musa not only conducted, as they would say now, party work, but also managed to write plays for children, songs, poems, and journalistic articles.

Poet Musa Jalil

Poet Musa Jalil At first, in the works, propaganda orientation and maximalism were intertwined with expressiveness and pathos, metaphors and conventions characteristic of Eastern literature. Later, Jalil preferred realistic descriptions with a touch of folklore.

Jalil gained wide fame while studying in Moscow. His classmates really liked Musa’s work; his poems were read at student evenings. The young talent was enthusiastically accepted into the capital's association of proletarian writers. Jalil met Alexander Zharov and saw the performances.

In 1934, a collection on Komsomol themes, “Order-Bearing Millions,” was published, followed by “Poems and Poems.” The works of the 30s demonstrated a deeply thinking poet, not alien to philosophy and able to use the whole palette expressive means language.

For the opera “Golden-haired”, which tells about the heroism of the Bulgar tribe, which did not submit to foreign invaders, the poet reworked the heroic epic “Jik Mergen”, fairy tales and legends of the Tatar people into a libretto. The premiere took place two weeks before the start of the war, and in 2011 the Tatar Opera and Ballet Theater, which, by the way, bears the name of the author, returned the production to its stage.

As composer Nazib Zhiganov later said, he asked Jalil to shorten the poem, as required by the laws of drama. Musa categorically refused, saying that he did not want to remove the lines written “with the blood of his heart.” The head of the literary department was remembered by a friend as a caring person, interested and concerned about Tatar musical culture.

Close friends told me how colorful literary language the poet described all sorts of funny stories that happened to him, and then read them out to the company. Jalil kept notes in the Tatar language, but after his death the notebook disappeared without a trace.

Musa Jalil's poem "Barbarism"In Hitler's dungeons, Musa Jalil wrote hundreds of poems, 115 of which reached his descendants. The top poetic creativity The cycle “Moabite Notebook” is considered.

These are indeed two miraculously preserved notebooks handed over to the Soviet authorities by the poet’s cellmates in the Moabit and Plötzensee camps. According to unconfirmed information, two more, who somehow fell into the hands of a Turkish citizen, ended up in the NKVD and disappeared there.

On the front line and in the camps, Musa wrote about the war, about the atrocities he witnessed, about the tragedy of the situation and his iron will. These were the poems “Helmet”, “Four Flowers”, “Azimuth”. The piercing lines “They and their children drove away the mothers...” from “Barbarism” eloquently describe the poet’s feelings.

There was a place in Jalil’s soul for lyrics, romanticism and humor, for example, “Love and a Runny Nose” and “Sister Inshar”, “Spring” and dedicated to his wife Amina “Farewell, my smart girl”.

Personal life

Musa Jalil was married more than once. Rouse's first wife gave the poet a son, Albert. He became a career officer, served in Germany, and kept his father’s first book with his autograph all his life. Albert raised two sons, but nothing is known about their fate.

In a civil marriage with Zakiya Sadykova, Musa gave birth to Lucia. The daughter graduated from the conducting department of the music school and the Moscow Institute of Cinematography, lived and taught in Kazan.

The poet's third wife's name was Amina. Although there is information spread on the Internet that according to the documents the woman was listed as either Anna Petrovna or Nina Konstantinovna. The daughter of Amina and Musa Chulpan Zalilova lived in Moscow and worked as an editor in a literary publishing house. Her grandson Mikhail, a talented violinist, bears the double surname Mitrofanov-Jalil.

Death

There would be no front-line or camp pages in Jalil’s biography if the poet had not refused the reservation given to him from military service. Musa came to the military registration and enlistment office on the second day after the start of the war, was assigned as a political instructor, and worked as a military correspondent. In 1942, emerging from encirclement with a detachment of fighters, Jalil was wounded and captured.

In a concentration camp near the Polish city of Radom, Musa joined the Idel-Ural legion. The Nazis gathered highly educated representatives of non-Slavic nations into groups with the aim of raising supporters and disseminators of fascist ideology.

Jalil, taking advantage of relative freedom of movement, launched subversive activities in the camp. The underground members were preparing to escape, but there was a traitor in their ranks. The poet and his most active associates were executed by guillotine.

Participation in the Wehrmacht unit gave reason to consider Musa Jalil a traitor to the Soviet people. Only after his death, thanks to the efforts of the Tatar scientist and public figure Gazi Kashshaf, the truth about the tragic and at the same time heroic last years of the poet’s life was revealed.

Bibliography

- 1925 – “We Are Coming”

- 1929 – “Comrades”

- 1934 – “Order-bearing millions”

- 1955 – “Heroic Song”

- 1957 – “The Moabit Notebook”

- 1964 – “Musa Jalil. Selected Lyrics"

- 1979 – “Musa Jalil. Selected Works"

- 1981 – “Red Daisy”

- 1985 – “The Nightingale and the Spring”

- 2014 – “Musa Jalil. Favorites"

Quotes

I know: with life, the dream will go away.

But with victory and happiness

She will dawn in my country,

No one has the power to hold back the dawn!

We will forever glorify that woman whose name is Mother.

Our youth imperiously dictates to us: “Seek!”

And storms of passions carry us around.

It was not the feet of men who paved the roads,

And the feelings and passions of people.

Why be surprised, dear doctor?

Helps our health

The best medicine of wondrous power,

What is called love.

The story of how, thanks to a notebook with poems, a man accused of treason against the Motherland was not only acquitted, but also received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, is known to few today. However, at one time they wrote about her in all newspapers former USSR. Its hero, Musa Jalil, lived only 38 years, but during this time he managed to create many interesting works. In addition, he proved that even in fascist concentration camps a person can fight the enemy and maintain the patriotic spirit in his fellow sufferers. This article presents a short biography of Musa Jalil in Russian.

Childhood

Musa Mustafovich Zalilov was born in 1906 in the village of Mustafino, which today is located in the Orenburg region. The boy was the sixth child in the traditional Tatar family of simple workers Mustafa and Rakhima.

WITH early age Musa began to show interest in studying and expressed his thoughts unusually beautifully.

At first, the boy studied at a mektebe - a village school, and when the family moved to Orenburg, he was sent to study at the Khusainiya madrasah. Already at the age of 10, Musa wrote his first poems. In addition, he sang and drew well.

After the revolution, the madrasah was transformed into the Tatar Institute of Public Education.

As a teenager, Musa joined the Komsomol, and even managed to fight on the fronts of the Civil War.

After its completion, Jalil took part in the creation of pioneer detachments in Tatarstan and promoted the ideas of young Leninists in his poems.

Musa's favorite poets were Omar Khayyam, Saadi, Hafiz and Derdmand. His passion for their work led to Jalil’s creation of such poetic works as “Burn, Peace,” “Council,” “Unanimity,” “In Captivity,” “Throne of Ears,” etc.

Study in the capital

In 1926, Musa Jalil (biography as a child is presented above) was elected a member of the Tatar-Bashkir Bureau of the Komsomol Central Committee. This allowed him to go to Moscow and enter the ethnological faculty of Moscow State University. In parallel with his studies, Musa wrote poetry in the Tatar language. Their translations were read at student poetry evenings.

In Tatarstan

In 1931, Musa Jalil, whose biography is practically unknown to Russian youth today, received a university diploma and was sent to work in Kazan. There, during this period, under the Central Committee of the Komsomol, children's magazines began to be published in Tatar. Musa began working as their editor.

A year later, Jalil left for the city of Nadezhdinsk (modern Serov). There he worked hard and hard on new works, including the poems “Ildar” and “Altyn Chech”, which in the future formed the basis for the libretto of operas by the composer Zhiganov.

In 1933, the poet returned to the capital of Tatarstan, where the Kommunist newspaper was published, and headed its literary department. He continued to write a lot and in 1934, 2 collections of Jalil’s poems, “Ordered Millions” and “Poems and Poems,” were published.

In the period from 1939 to 1941, Musa Mustafaevich worked at the Tatar Opera Theater as the head of the literary department and secretary of the Writers' Union of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

War

June 23, 1941 Musa Jalil, whose biography reads as tragic romance, came to his military registration and enlistment office and wrote a statement with a request to be sent to the active army. The summons arrived on July 13, and Jalil ended up in artillery regiment, formed on the territory of Tatarstan. From there, Musa was sent to Menzelinsk for a 6-month course for political instructors.

When Jalil's command became aware of what was in front of them famous poet, a deputy of the City Council and former chairman of the Tatar Writers' Union, it was decided to issue an order for his demobilization and sending to the rear. However, he refused, because he believed that the poet could not call on people to defend their Motherland while in the rear.

Nevertheless, they decided to protect Jalil and kept him in reserve at the army headquarters, which was then located in Malaya Vishera. At the same time, he often went on business trips to the front line, carrying out orders from the command and collecting material for the newspaper “Courage”.

In addition, he continued to write poetry. In particular, such works as “Tear”, “Death of a Girl”, “Trace” and “Farewell, My Smart Girl” were born at the front.

Unfortunately, the reader did not reach the poem “The Ballad of the Last Patron,” which the poet wrote shortly before his capture in a letter to a comrade.

Wound

In June 1942, together with other soldiers and officers, Musa Jalil (biography in last year the poet's life became known only after the death of the hero) was surrounded. Trying to break through to his own people, he was seriously wounded in the chest. Since Musa had no one to help medical care, he began an inflammatory process. The advancing Nazis found him unconscious and took him prisoner. From that moment on, the Soviet command began to consider Jalil missing.

Captivity

Musa's comrades in the concentration camp tried to protect their wounded friend. They hid from everyone that he was a political instructor and tried to prevent him from doing hard work. Thanks to their care, Musa Jalil (his biography in the Tatar language was known to every schoolchild at one time) recovered and began to provide assistance to other prisoners, including moral assistance.

It’s hard to believe, but he was able to get a stub of a pencil and wrote poetry on scraps of paper. In the evenings they were read by the whole barracks, remembering the Motherland. These works helped prisoners survive all difficulties and humiliation.

While wandering through the camps of Spandau, Plötzensee and Moabit, Jalil continued to encourage the spirit of resistance among Soviet prisoners of war.

“Responsible for cultural and educational work”

After the defeat at Stalingrad, the Nazis decided to create a legion of Soviet prisoners of war of Tatar nationality, supporting the principle of “Divide and conquer.” This military unit was named “Idel-Ural”.

Musa Jalil (the biography in Tatar was republished several times) was in the special regard of the Germans, who wanted to use the poet for propaganda purposes. He was included in the legion and appointed to lead cultural and educational work.

In Jedlinsk, near the Polish city of Radom, where Idel-Ural was formed, Musa Jalil (a biography in the Tatar language is kept in the poet’s museum) became a member of an underground group of Soviet prisoners of war.

As an organizer of concerts designed to create a spirit of resistance against Soviet authorities, who “oppressed” the Tatars and representatives of other nationalities, he had to travel a lot to German concentration camps. This allowed Jalil to find and recruit more and more new members for the underground organization. As a result, members of the group even managed to contact underground fighters from Berlin.

At the beginning of the winter of 1943, the 825th battalion of the legion was sent to Vitebsk. There he raised an uprising, and about 500 people were able to go to the partisans along with their service weapons.

Arrest

At the end of the summer of 1943, Musa Jalil (you already know his brief biography in his youth), together with other underground fighters, was preparing an escape for several prisoners sentenced to death.

The group's last meeting took place on August 9. On it, Jalil informed his comrades that contact with the Red Army had been established. The underground planned the start of the uprising for August 14. Unfortunately, among the resistance members there was a traitor who betrayed their plans to the Nazis.

On August 11, all “cultural educators” were called to the dining room “for a rehearsal.” There they were all arrested, and Musa Jalil (his biography in Russian is in many Christians of Soviet literature) was beaten in front of the detainees to intimidate them.

In Moabit

He, along with 10 comrades, was sent to one of the Berlin prisons. There Jalil met Belgian resistance member Andre Timmermans. Unlike Soviet prisoners, citizens of other states in Nazi dungeons had the right to correspondence and received newspapers. Having learned that Musa was a poet, the Belgian gave him a pencil and regularly handed over strips of paper cut from newspapers. Jalil stitched them into small notebooks in which he wrote down his poems.

The poet was executed by guillotine at the end of August 1944 in the Plötzensee prison in Berlin. The location of the graves of Jalil and his comrades is still unknown.

Confession

After the war in the USSR, a search was opened against the poet and he was included in the list of especially dangerous criminals, as he was accused of treason and collaboration with the Nazis. Musa Jalil, whose biography in Russian, as well as his name, were removed from all books about Tatar literature, would probably have remained slandered if not for the former prisoner of war Nigmat Teregulov. In 1946, he came to the Writers' Union of Tatarstan and handed over a notebook with the poet's poems, which he miraculously managed to take out of the German camp. A year later, the Belgian Andre Timmermans handed over a second notebook with Jalil’s works to the Soviet consulate in Brussels. He said that he was with Musa in fascist dungeons and saw him before his execution.

Thus, 115 of Jalil’s poems reached readers, and his notebooks are now kept in the State Museum of Tatarstan.

All this would not have happened if Konstantin Simonov had not found out about this story. The poet organized the translation of “Moabit Tetarads” into Russian and proved the heroism of the underground fighters under the leadership of Musa Jalil. Simonov wrote an article about them, which was published in 1953. Thus, the stain of shame was washed away from Jalil’s name, and the entire Soviet Union learned about the feat of the poet and his comrades.

In 1956, the poet was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, and a little later he became a laureate of the Lenin Prize.

Biography of Musa Jalil (summary): family

The poet had three wives. From his first wife Rauza Khanum he had a son, Albert Zalilov. Jalil loved his only boy very much. He wanted to become a military pilot, but due to an eye disease he was not accepted into the flight school. However, Albert Zalilov became a military man and in 1976 was sent to serve in Germany. He stayed there for 12 years. Thanks to his searches in different parts of the Soviet Union, it became known detailed biography Musa Jalil in Russian.

The poet's second wife was Zakiya Sadykova, who gave birth to his daughter Lucia.

The girl and her mother lived in Tashkent. She studied at a music school. Then she graduated from VGIK, and she was lucky enough to take part in the filming of the documentary film “The Moabit Notebook” as an assistant director.

Jalil's third wife, Amina, gave birth to another daughter. The girl was named Chulpan. She, like her father, devoted about 40 years of her life to literary activity.

Now you know who Musa Jalil was. Brief biography This poet's Tatar language should be studied by all schoolchildren in his small homeland.

Musa Mostafa uly Җәlilov, Musa Mostafa ulı Cəlilov; February 2 (15), Mustafino village, Orenburg province (now Mustafino, Sharlyk district, Orenburg region) - August 25, Berlin) - Tatar Soviet poet, Hero of the Soviet Union (), Lenin Prize laureate (posthumously). Member of the CPSU(b) since 1929.Biography

Born the sixth child in the family. Father - Mustafa Zalilov, mother - Rakhima Zalilova (nee Sayfullina).

Posthumous recognition

The first work was published in 1919 in the military newspaper “Kyzyl Yoldyz” (“Red Star”). In 1925, his first collection of poems and poems “Barabyz” (“We are coming”) was published in Kazan. He wrote 4 librettos for the operas “Altyn chәch” (“Golden-haired”, music by composer N. Zhiganov) and “Ildar” ().

In the 1920s, Jalil wrote on the topics of revolution and civil war(poem “Traveled Paths”, -), construction of socialism (“Order-bearing millions”; “The Letter Bearer”, )

The popular poem “The Letter Bearer” (“Khat Tashuchy”, 1938, published 1940) shows the working life of the owls. youth, its joys and experiences.

In the concentration camp, Jalil continued to write poetry, in total he wrote at least 125 poems, which after the war were transferred to his homeland by his cellmate. For the cycle of poems “The Moabit Notebook” in 1957, Jalil was posthumously awarded the Lenin Prize by the Committee for Lenin and State Prizes in Literature and Art. In 1968, the film The Moabit Notebook was made about Musa Jalil.

Memory

The following are named after Musa Jalil:

Museums of Musa Jalil are located in Kazan (M. Gorky St., 17, apt. 28 - the poet lived here in 1940-1941) and in his homeland in Mustafino (Sharlyksky district, Orenburg region).

Monuments to Musa Jalil were erected in Kazan (complex on May 1 Square in front of the Kremlin), Almetyevsk, Menzelinsk, Moscow (opened on October 25, 2008 on Belorechenskaya Street and on August 24, 2012 on the street of the same name (on illustration)), Nizhnekamsk (opened August 30, 2012), Nizhnevartovsk (opened September 25, 2007), Naberezhnye Chelny, Orenburg, St. Petersburg (opened May 19, 2011), Tosno (opened November 9, 2012), Chelyabinsk (opened October 16 2015).

On the wall of the arched gate of the broken 7th counterguard in front of the Mikhailovsky Gate of the Daugavpils Fortress (Daugavpils, Latvia), where from September 2 to October 15, 1942, Musa was kept in the camp for Soviet prisoners of war "Stalag-340" Jalil, a memorial plaque has been installed. The text is provided in Russian and Latvian. Also engraved on the board are the words of the poet: “I have always dedicated songs to the Fatherland, now I give my life to the Fatherland...”.

In cinema

- “The Moabit Notebook”, dir. Leonid Kvinikhidze, Lenfilm, 1968.

- "Red Daisy", DEFA (GDR).

Bibliography

- Musa Jalil. Works in three volumes / Kashshaf G. - Kazan, 1955-1956 (in Tatar language).

- Musa Jalil. Essays. - Kazan, 1962.

- Musa Jalil./ Ganiev V. - M.: Fiction, 1966.

- Musa Jalil. Favorites. - M., 1976.

- Musa Jalil. Selected works / Mustafin R. - Publishing house " Soviet writer" Leningrad branch, 1979.

- Musa Jalil. A fire over a cliff. - M., Pravda, 1987. - 576 pp., 500,000 copies.

See also

Write a review about the article "Musa Jalil"

Notes

Literature

- Bikmukhamedov R. Musa Jalil. Critical and biographical essay. - M., 1957.

- Gosman H. Tatar poetry of the twenties. - Kazan, 1964 (in Tatar).

- Vozdvizhensky V. History of Tatar Soviet literature. - M., 1965.

- Fayzi A. Memories of Musa Jalil. - Kazan, 1966.

- Akhatov G. Kh. About the language of Musa Jalil / “Socialist Tatarstan”. - Kazan, 1976, No. 38 (16727), February 15.

- Akhatov G. Kh. Phraseological phrases in Musa Jalil’s poem “The Scribe.” / Zh. “Soviet school”. - Kazan, 1977, No. 5 (in Tatar).

- Mustafin R.A. In the footsteps of the poet-hero. Search book. - M.: Soviet writer, 1976.

- Korolkov Yu.M. Forty deaths later. - M.: Young Guard, 1960.

- Korolkov Yu.M. Life is a song. The life and struggle of the poet Musa Jalil. - M.: Gospolitizdat, 1959.

Links

Website "Heroes of the Country".

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- . (Tatar.) .

- . (Tatar) , (Russian) .

Excerpt characterizing Musa Jalil

- Why agree, we don’t need bread.- Well, should we give it all up? We don't agree. We don’t agree... We don’t agree. We feel sorry for you, but we do not agree. Go on your own, alone...” was heard in the crowd with different sides. And again the same expression appeared on all the faces of this crowd, and now it was probably no longer an expression of curiosity and gratitude, but an expression of embittered determination.

“You didn’t understand, right,” said Princess Marya with a sad smile. - Why don’t you want to go? I promise to house you and feed you. And here the enemy will ruin you...

But her voice was drowned out by the voices of the crowd.

“We don’t have our consent, let him ruin it!” We don’t take your bread, we don’t have our consent!

Princess Marya again tried to catch someone's gaze from the crowd, but not a single glance was directed at her; the eyes obviously avoided her. She felt strange and awkward.

- See, she taught me cleverly, follow her to the fortress! Destroy your home and go into bondage and go. Why! I'll give you the bread, they say! – voices were heard in the crowd.

Princess Marya, lowering her head, left the circle and went into the house. Having repeated the order to Drona that there should be horses for departure tomorrow, she went to her room and was left alone with her thoughts.

For a long time that night, Princess Marya sat at the open window in her room, listening to the sounds of men talking coming from the village, but she did not think about them. She felt that no matter how much she thought about them, she could not understand them. She kept thinking about one thing - about her grief, which now, after the break caused by worries about the present, had already become past for her. She could now remember, she could cry and she could pray. As the sun set, the wind died down. The night was quiet and fresh. At twelve o'clock the voices began to fade, the rooster crowed, and people began to emerge from behind the linden trees. full moon, a fresh, white mist of dew rose, and silence reigned over the village and over the house.

One after another, pictures of the close past appeared to her - illness and her father’s last minutes. And with sad joy she now dwelled on these images, driving away from herself with horror only one last image of his death, which - she felt - she was unable to contemplate even in her imagination at this quiet and mysterious hour of the night. And these pictures appeared to her with such clarity and with such detail that they seemed to her now like reality, now the past, now the future.

Then she vividly imagined that moment when he had a stroke and was dragged out of the garden in the Bald Mountains by the arms and he muttered something with an impotent tongue, twitched his gray eyebrows and looked at her restlessly and timidly.

“Even then he wanted to tell me what he told me on the day of his death,” she thought. “He always meant what he told me.” And so she remembered in all its details that night in Bald Mountains on the eve of the blow that happened to him, when Princess Marya, sensing trouble, remained with him against his will. She did not sleep and at night she tiptoed downstairs and, going up to the door to the flower shop where her father spent the night that night, listened to his voice. He said something to Tikhon in an exhausted, tired voice. He obviously wanted to talk. “And why didn’t he call me? Why didn’t he allow me to be here in Tikhon’s place? - Princess Marya thought then and now. “He will never tell anyone now everything that was in his soul.” This moment will never return for him and for me, when he would say everything he wanted to say, and I, and not Tikhon, would listen and understand him. Why didn’t I enter the room then? - she thought. “Maybe he would have told me then what he said on the day of his death.” Even then, in a conversation with Tikhon, he asked about me twice. He wanted to see me, but I stood here, outside the door. He was sad, it was hard to talk with Tikhon, who did not understand him. I remember how he spoke to him about Lisa, as if she were alive - he forgot that she died, and Tikhon reminded him that she was no longer there, and he shouted: “Fool.” It was hard for him. I heard from behind the door how he lay down on the bed, groaning, and shouted loudly: “My God! Why didn’t I get up then?” What would he do to me? What would I have to lose? And maybe then he would have been consoled, he would have said this word to me.” And Princess Marya said out loud the kind word that he said to her on the day of his death. “Darling! – Princess Marya repeated this word and began to sob with soul-easing tears. She now saw his face in front of her. And not the face that she had known since she could remember, and which she had always seen from afar; and that face - timid and weak, which on the last day, bending down to his mouth to hear what he said, she examined up close for the first time with all its wrinkles and details.

“Darling,” she repeated.

“What was he thinking when he said that word? What is he thinking now? - suddenly a question came to her, and in response to this she saw him in front of her with the same expression on his face that he had in the coffin on his face tied with a white scarf. And the horror that gripped her when she touched him and became convinced that it was not only not him, but something mysterious and repulsive, gripped her now. She wanted to think about other things, wanted to pray, but could do nothing. She looked with large open eyes at the moonlight and shadows, every second she expected to see his dead face and felt that the silence that stood over the house and in the house shackled her.

- Dunyasha! – she whispered. - Dunyasha! – she screamed in a wild voice and, breaking out of the silence, ran to the girls’ room, towards the nanny and girls running towards her.

On August 17, Rostov and Ilyin, accompanied by Lavrushka, who had just returned from captivity, and the messenger hussar, from their Yankovo camp, fifteen miles from Bogucharovo, went horseback riding - to try a new horse, bought by Ilyin, and to find out if there was any hay in the villages.

Bogucharovo had been located for the last three days between two enemy armies, so that the Russian rearguard could have entered there just as easily as the French vanguard, and therefore Rostov, as a caring squadron commander, wanted to take advantage of the provisions that remained in Bogucharovo before the French.

Rostov and Ilyin were in the most cheerful mood. On the way to Bogucharovo, to the princely estate with an estate, where they hoped to find large servants and pretty girls, they either asked Lavrushka about Napoleon and laughed at his stories, or drove around, trying Ilyin’s horse.

Rostov neither knew nor thought that this village to which he was traveling was the estate of that same Bolkonsky, who was his sister’s fiancé.

Rostov and Ilyin let the horses out for the last time to drive the horses into the drag in front of Bogucharov, and Rostov, having overtaken Ilyin, was the first to gallop into the street of the village of Bogucharov.

“You took the lead,” said the flushed Ilyin.

“Yes, everything is forward, and forward in the meadow, and here,” answered Rostov, stroking his soaring bottom with his hand.

“And in French, your Excellency,” Lavrushka said from behind, calling his sled nag French, “I would have overtaken, but I just didn’t want to embarrass him.”

They walked up to the barn, near which stood a large crowd of men.

Some men took off their hats, some, without taking off their hats, looked at those who had arrived. Two long old men, with wrinkled faces and sparse beards, came out of the tavern and, smiling, swaying and singing some awkward song, approached the officers.

- Well done! - Rostov said, laughing. - What, do you have any hay?

“And they are the same...” said Ilyin.

“Vesve...oo...oooo...barking bese...bese...” the men sang with happy smiles.

One man came out of the crowd and approached Rostov.

- What kind of people will you be? he asked.

“The French,” Ilyin answered, laughing. “Here is Napoleon himself,” he said, pointing to Lavrushka.

- So, you will be Russian? – the man asked.

- How much of your strength is there? – asked another small man, approaching them.

“Many, many,” answered Rostov. - Why are you gathered here? - he added. - A holiday, or what?

“The old people have gathered on worldly business,” the man answered, moving away from him.

At this time, along the road from the manor's house, two women and a man in a white hat appeared, walking towards the officers.

- Mine in pink, don’t bother me! - said Ilyin, noticing Dunyasha resolutely moving towards him.

- Ours will be! – Lavrushka said to Ilyin with a wink.

- What, my beauty, do you need? - Ilyin said, smiling.

- The princess ordered to find out what regiment you are and your last names?

“This is Count Rostov, squadron commander, and I am your humble servant.”

- B...se...e...du...shka! - the drunk man sang, smiling happily and looking at Ilyin talking to the girl. Following Dunyasha, Alpatych approached Rostov, taking off his hat from afar.

“I dare to bother you, your honor,” he said with respect, but with relative disdain for the youth of this officer and putting his hand in his bosom. “My lady, the daughter of General Chief Prince Nikolai Andreevich Bolkonsky, who died this fifteenth, being in difficulty due to the ignorance of these persons,” he pointed to the men, “asks you to come... would you like,” Alpatych said with a sad smile, “to leave a few, otherwise it’s not so convenient when... - Alpatych pointed to two men who were running around him from behind, like horseflies around a horse.

- A!.. Alpatych... Eh? Yakov Alpatych!.. Important! forgive for Christ's sake. Important! Eh?.. – the men said, smiling joyfully at him. Rostov looked at the drunken old men and smiled.

– Or perhaps this consoles your Excellency? - said Yakov Alpatych with a sedate look, pointing at the old people with his hand not tucked into his bosom.

“No, there’s little consolation here,” Rostov said and drove off. -What's the matter? he asked.

“I dare to report to your excellency that the rude people here do not want to let the lady out of the estate and threaten to turn away the horses, so in the morning everything is packed and her ladyship cannot leave.”

- Can't be! - Rostov screamed.

“I have the honor to report to you the absolute truth,” Alpatych repeated.

Rostov got off his horse and, handing it over to the messenger, went with Alpatych to the house, asking him about the details of the case. Indeed, yesterday’s offer of bread from the princess to the peasants, her explanation with Dron and the gathering spoiled the matter so much that Dron finally handed over the keys, joined the peasants and did not appear at Alpatych’s request, and that in the morning, when the princess ordered the laying to go, the peasants came out in a large crowd to the barn and sent to say that they would not let the princess out of the village, that there was an order not to be taken out, and they would unharness the horses. Alpatych came out to them, admonishing them, but they answered him (Karp spoke most of all; Dron did not appear from the crowd) that the princess could not be released, that there was an order for that; but let the princess stay, and they will serve her as before and obey her in everything.

At that moment, when Rostov and Ilyin galloped along the road, Princess Marya, despite the dissuading of Alpatych, the nanny and the girls, ordered the laying and wanted to go; but, seeing the galloping cavalrymen, they were mistaken for the French, the coachmen fled, and the crying of women arose in the house.

- Father! dear father! “God sent you,” said tender voices, while Rostov walked through the hallway.

Princess Marya, lost and powerless, sat in the hall while Rostov was brought to her. She did not understand who he was, and why he was, and what would happen to her. Seeing him Russian face and upon his entrance and the first words spoken, recognizing him as a man of her circle, she looked at him with her deep and radiant gaze and began to speak in a voice that was broken and trembling with emotion. Rostov immediately imagined something romantic in this meeting. “A defenseless, grief-stricken girl, alone, left at the mercy of rude, rebellious men! And some strange fate pushed me here! - Rostov thought, listening to her and looking at her. - And what meekness, nobility in her features and expression! – he thought, listening to her timid story.

When she spoke about the fact that all this happened the day after her father’s funeral, her voice trembled. She turned away and then, as if afraid that Rostov would take her words for a desire to pity him, she looked at him inquiringly and fearfully. Rostov had tears in his eyes. Princess Marya noticed this and looked gratefully at Rostov with that radiant look of hers, which made one forget the ugliness of her face.

“I can’t express, princess, how happy I am that I came here by chance and will be able to show you my readiness,” said Rostov, getting up. “Please go, and I answer you with my honor that not a single person will dare to make trouble for you, if you only allow me to escort you,” and, bowing respectfully, as they bow to ladies of royal blood, he headed to the door.

By the respectful tone of his tone, Rostov seemed to show that, despite the fact that he would consider his acquaintance with her a blessing, he did not want to take advantage of the opportunity of her misfortune to get closer to her.

Princess Marya understood and appreciated this tone.

“I am very, very grateful to you,” the princess told him in French, “but I hope that all this was just a misunderstanding and that no one is to blame for it.” “The princess suddenly began to cry. “Excuse me,” she said.

Rostov, frowning, bowed deeply again and left the room.

- Well, honey? No, brother, my pink beauty, and their name is Dunyasha... - But, looking at Rostov’s face, Ilyin fell silent. He saw that his hero and commander was in a completely different way of thinking.

Rostov looked back angrily at Ilyin and, without answering him, quickly walked towards the village.

“I’ll show them, I’ll give them a hard time, the robbers!” - he said to himself.

Alpatych, at a swimming pace, so as not to run, barely caught up with Rostov at a trot.

– What decision did you decide to make? - he said, catching up with him.

Rostov stopped and, clenching his fists, suddenly moved menacingly towards Alpatych.

- Solution? What's the solution? Old bastard! - he shouted at him. -What were you watching? A? Men are rebelling, but you can’t cope? You yourself are a traitor. I know you, I’ll skin you all...” And, as if afraid to waste his reserve of ardor in vain, he left Alpatych and quickly walked forward. Alpatych, suppressing the feeling of insult, kept up with Rostov at a floating pace and continued to communicate his thoughts to him. He said that the men were stubborn, that at the moment it was unwise to oppose them without having a military command, that it would not be better to send for a command first.

“I’ll give them a military command... I’ll fight them,” Nikolai said senselessly, suffocating from unreasonable animal anger and the need to vent this anger. Not realizing what he would do, unconsciously, with a quick, decisive step, he moved towards the crowd. And the closer he moved to her, the more Alpatych felt that his unreasonable act could produce good results. The men of the crowd felt the same, looking at his fast and firm gait and decisive, frowning face.

After the hussars entered the village and Rostov went to the princess, there was confusion and discord in the crowd. Some men began to say that these newcomers were Russians and how they would not be offended by the fact that they did not let the young lady out. Drone was of the same opinion; but as soon as he expressed it, Karp and other men attacked the former headman.

– How many years have you been eating the world? - Karp shouted at him. - It’s all the same to you! You dig up the little jar, take it away, do you want to destroy our houses or not?

- It was said that there should be order, no one should leave the house, so as not to take out any blue gunpowder - that’s all it is! - shouted another.

“There was a line for your son, and you probably regretted your hunger,” the little old man suddenly spoke quickly, attacking Dron, “and you shaved my Vanka.” Eh, we're going to die!

- Then we’ll die!

“I am not a refuser from the world,” said Dron.

- He’s not a refusenik, he’s grown a belly!..

Two long men had their say. As soon as Rostov, accompanied by Ilyin, Lavrushka and Alpatych, approached the crowd, Karp, putting his fingers behind his sash, slightly smiling, came forward. The drone, on the contrary, entered the back rows, and the crowd moved closer together.