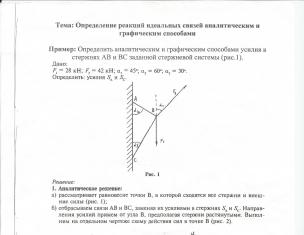

§ 1. General idea of current state equivalence theory

Have you read Dan Brown? Paolo Coelho? Haruki Murakami?

In original?!

When we read the books discussed above, we mean translations, but we do not realize that these are translations. It takes a special effort to realize this. This happens because. That there is an idea in society that a translation replaces the original in the receiving culture, that it is, as it were, the original. It is paradoxical that whatever the real relationship between the translation and the original, these texts are perceived/assumed by the recipients to be identical. The translator cannot ignore this phenomenon and strives to justify the expectations placed on him by society and create a text that, in its properties, is as close as possible to the original, being its communicative and functional replacement/similarity. As a result, certain relationships are assumed and established between the translation and the original texts. The presence of these relationships also stems from the fact that translation is not just an act of free text generation, it arises on the basis of the original, representing a secondary text.

These relations are usually defined through the category of equivalence. Τᴀᴋᴎᴍ ᴏϬᴩᴀᴈᴏᴍ to perform the same function as the original, translation must be equivalent to the original.

Concept equivalence translation to the original is the central and, without a doubt, the most controversial concept of translation theory. This is largely due to the fact that this category is not objective, but subjective.

Posted on ref.rf

The reason for this subjectivity is the following: most theories are based on the translation of fiction or even poetry, and this is a special (and very specific) case of translation. Perception of a literary text even at native language variably (you didn’t understand anything from Dostoevsky!) The translator is just a reader - translation is one of many possible interpretations. The very nature of a literary text lies in uncertainty, diversity, in this meaning and purpose artistic word. How then can we talk about equivalence against the background of translation variability? But for the recipient of the transfer, any transfer is equivalent, ᴛ.ᴇ. is perceived as such. Pragmatically, the translation text functions as an equivalent. Again, subjective nature. Those. It's not a rigid system.

In the very general view equivalence is understood as a certain relationship between the translation and the original, as the correspondence of the translation to the original, but when trying to specify this general idea turns out not so easy to determine. What should this commonality consist of? To what extent should it exist so that a certain text created on the basis of the original can be considered its translation and by what criteria should it be assessed?

We have already encountered this concept as part of the introductory lectures, but we did not use this term in order to consolidate the very understanding of its modern content.

There are many theories of equivalence, from a strictly linguistic approach to understanding this term to a denial of its value for translation theory. There are three basic approaches to defining this term:

1) general universal definition; the real embodiment of which is illustrated using examples of texts of different functional orientations.

I.S. Alekseeva: modern understanding text equivalence is to achieve the maximum possible similarity of two texts, which only the most qualified translator is capable of, and not their identity/translation is not a copy of the original in the literal sense of the word. Equivalence in translation should not be approached as a search for sameness, since sameness can not even exist between versions in one language.

Equivalence is the maximum commonality of the content of two multilingual texts, allowed by differences in languages. Under the content, in this case V.N. Commissioners understands the presence in any statement of 1) the purpose of communication expressed through 2) a description of any situation, carried out through the selection of 3) some of its features, which at the surface level are represented by linguistic units organized in a certain 4) syntactic way and having a certain 5) linguistic meaning, ĸᴏᴛᴏᴩᴏᴇ, in turn, consists of denotative, connotative and intralinguistic.

2) determination of equivalence through demonstration of its specific types. Those. equivalence in relation to a specific type of text consists in preserving one or another aspect of the content of the original, recognized as invariant. Giuliana Garzone, 2001: ʼʼThere are more than 50 definitions, some being split into “kinds”, because authors see it impossible to give a universal one, they single out only one textual feature to the detriment of others, which is rather practical than theoreticalʼʼ.

3) Refusal to use this term. The reason for this is an extremely utilitarian, pragmatic approach to understanding translation activity. Main functionalist principle – choices are subordinated to the purpose of translation. In the extreme manifestation called SKOPOS ( Hans Vermeer, K. Reiss). They substitute the much used and abused term equivalence with adequacy, which means correspondence of the TT with the function it is supposed to have in the Tculture. Thus, TS have seen “dethronement” of ST. Extreme formulation of SKOPOS theory: translation – an offer of information in the TL about an offer of info in the SL. M.Baker: equivalence is used “for the sake of convenience – because most translators are used to it rather than because it has any theoretical status”.

It is known that in order to determine any scientific concept it is extremely important to establish its relationship with other concepts in the field of knowledge under consideration.

The concept of equivalence is closely related to the concept invariant translation. An invariant is often understood as a set of certain properties of the original that are preserved in the translation. Naturally, researchers who define equivalence differently (ᴛ.ᴇ. formulate the purpose of translation differently) include in this set various text properties. At the same time, in any case, the invariance of translation ensures its equivalence.

Popovic:“invariant core – stable, basic and constant semantic elements in the text whose existence can be proven by experimental semantic condensation. Alekseeva: invariant is the relationship between the content of the text and the situational context͵ different for each specific text and representing its communicative task (the meaning of linguistic units vs content as the meaning realized in speech; content vs function of the text͵ the function is realized through the content, but is different from it. To for example, “Well, you’re great!” – one content – different functions, “Don’t forget to pay the fare”, “Who else has entered?” - different content – one function.

The invariant can include any elements of the text’s content, from the most obvious denotative ones to sometimes inconspicuous intertextualisms and stylistic features of the text. We must not forget that various elements of the content of the text are characterized by a greater or lesser degree of importance for the original text, ᴛ.ᴇ. are arranged hierarchically based on the functional load they carry in the text. This determines their inclusion in the invariant, and therefore their relevance for assessing the equivalence of the text. Neubert: Translation equivalence is defined as a semeotic category comprising syntactic, semantic and pragmatic components of the text that are arranged hierarchically, pragmatic one of paramount importance.

The functional content must remain unchanged (invariant) (R. Jacobson identifies the following functions of the utterance - denotative, expressive, poetic, metalinguistic, phatic + “imperative”), ᴛ.ᴇ. the semantic and pragmatic side of the original, determined by the communicative attitude and functional characteristics of the utterance, as well as their relationship. It must be borne in mind that the functional dominant can vary even within the same text; therefore, before translating, it is extremely important to determine it for each segment of the translation. The provision on the functional invariant does not remove the provisions on the semantic and syntactic invariant, since it includes them: an important function of any communicative act is the transfer of information. At the same time, this position has great explanatory power, because also covers those cases where the main function of the text is not a denotative function.

Another concept in translation theory related to the concept of equivalence is the concept adequacy of translation.

In their everyday meaning, these two words are never confused, and analysis of their general linguistic usage can serve as the basis for their terminological differentiation. Equivalence, outside of linguistic terminology, is used as a synonym for equivalence, equivalence, as an “equal” sign: equivalent remuneration (equal in value to the labor expended), the concept of equivalent diameter, ᴛ.ᴇ. about the linear size of a particle, equivalent diameter of the corresponding ball, these two bags of rice are equivalent to each other. We use adequacy in a different way - as a characteristic of an action: an adequate decision, behavior, reaction. What doesn't require clarification? because assumed to be normal. HELL. Schweitzer defines it as the correspondence of the selected linguistic sign of the TL to the aspect of IT that is chosen as the main reference point for the translation process. He also notes that this term, unlike equivalence, is focused on the translation process, and not on its result. At the same time, if the equivalence requirement, as we have already said, is a maximum requirement, implying exhaustive transfer of the communicative-functional invariant of IT, then a certain compromise solution, the degree of compliance that is actually achievable in a particular case, should be called adequate. Moreover, the adequacy of translation is a characteristic of its dynamic aspect, it is associated with the conditions of the act of interlingual communication, the compliance of the translation version with the chosen strategy, which, in turn, corresponds to the communicative situation. Consequently, in practice there may be cases when the unequal transmission of some text fragments should be recognized as an adequate solution, but not vice versa.

I think that an equivalent translation is possible in a situation where there is no contradiction between the two tasks, when the transfer of the maximum amount of content ensures the transfer of the functions of the text. Then the concepts of equivalence and adequacy coincide.

§ 2. Basic concepts of translation equivalence

Let's look at some concepts of equivalence in their historical development. This concept has developed from an understanding of equivalence as the sum of the meanings of IT words equal to the sum of the meanings of PT words to the current understanding: the maximum commonality of the content of IT and PT, allowed by differences in languages (Komissarov). When perceiving a statement, the Receptor must not only understand the meaning of linguistic units and their connection, but also draw certain conclusions from all the content - what he wants to say by this. It is worth emphasizing that these concepts were an organic development of religious, literary and social scientific views that existed in different historical eras and formed in close connection with them; they corresponded to the level of development of social consciousness and culture. Nevertheless, throughout the entire history of written languages, and, therefore, translation, 5 basic historically established theories have repeatedly replaced each other, making circle after circle in the endless spiral of human knowledge, each time enriched by the experience of the past and improved, but nevertheless preserving its essential features.

The oldest concept known to us is called the concept formal compliance . This concept appears to have served as the basis for written translation in ancient times. The bulk of translated literature at that time consisted of biblical and religious texts, which created special conditions for the formation of appropriate views on translation. As you know, the Bible was revered as a hypostasis of God, the word of God, recorded by those who were directly involved with God - the apostles. Universal illiteracy and faith made the text itself a shrine. The word of the Bible was considered inviolable because it was given by God in exactly this form. This gave rise to the iconic theory of the linguistic sign, which asserts the involuntary connection between the form and content of the sign. Consequently, translation was essentially sacrilege; only the original word could be truly sacred. At the same time, the urgent and extreme importance of spreading Christianity required the creation of foreign-language Bibles. The translation work was carried out in monasteries by the most educated priests, who sought to reflect as fully as possible the entire amount of information contained in the Holy Scriptures. In accordance with the concept of formal correspondence, which arose as a theoretical understanding of this goal, in translation, first of all, the FORM of the original was copied, while the content was often sacrificed. As a result, the translation text turned out to be dark and incomprehensible due to its literalness and overload with intralinguistic information, and the widespread use of transliteration (mamoth - mamon). This did not in any way detract from its religious significance, since it was believed that understanding God’s plan was beyond human power. Ancient translations of the Bible are replete with absurdities, sometimes resulting from repeated typos (the camel and the eye of the coal), yet the reverence for the text was so great that changes to it unauthorized by the higher clergy led to serious social upheavals (Martin Luther's Reform 16 century, Nikon split 18th century). This concept becomes popular whenever text-worship emerges in society. For example, A. Fet, as a translator, sought to preserve the form in the verse: the number of syllables, rhyme, size of the verse, caring little about the content. Interlinear translations for scientific purposes.

The first verse of Virgil's Aeneid translated by V. Bryusov sounds like this: “I am the one who once sang a song on a gentle pipe and, leaving the forests, prompted the neighboring fields, so that they obey the peasant, even the greedy one (labor, dear to the farmers), - and now I sing the terrible Martha’s abuse and the hero’s, from the coasts of Troy, whoever first arrived in Italy was expelled by fate...ʼʼ

In concept regulatory and content compliance

The main goal of the translator is!) to convey full content IT!!) subject to non-applicable compliance with PJ standards. It is the antipode of the previous one and existed in ancient times as its alternative for interpretation. Luther was the first to formulate the idea of such an approach to translation.

Posted on ref.rf

Guided by these ideas, he made new translation Bibles in Middle High German, and following the second requirement of this concept, he relied on the one hand on the common people, street language, and on the other on the clerical language. After all, by that time national literary norms had not yet been formed. With the advent of the language norm, this concept developed and is still the basis for oral official translation and all information translations.

Concept of Aesthetic Compliance consists in approaching the original text as raw material. The translator’s task is to create a certain ideal text in IT-based TL. The criteria for “ideality” varied in different centuries, but they were traditionally associated with the characteristics of the dominant literary direction: classicism and its principles of aesthetics Nicolò Boileau (compliance with a predetermined template), romanticism and its subjectivism, flights of fancy, decorations. For example, the ballad "Lenore" by Gottfried August Burger was translated by the romantic Zhukovsky three times: "Lyudmila" ("Russian ballad. Imitation of Birgerova Leonora") in Ancient Rus', ʼʼSvetlanaʼʼ - contemporary Moscow, ʼʼLenoraʼʼ in Germany. Translator competitions are typical: Pavel Katenin ʼʼOlgaʼʼ, “Natasha” competed with Zhukovsky ( the last Pushkin thought best example ballads). From school lesson literature: Zhukovsky’s ballad “Svetlana” is associated with Russian customs and beliefs, and the song and fairy tale tradition. The subject of the ballad is fortune telling by a girl on Epiphany evening.

Posted on ref.rf

The image of Svetlana is the first artistically convincing, psychologically truthful image of a Russian girl in Russian poetry. She is sometimes silent and sad, yearning for her missing groom, sometimes fearful and timid during fortune-telling, sometimes distracted and alarmed, not knowing what awaits her - typical of sentimentalism. V. A. Zhukovsky gained fame as an original writer precisely as the creator of ballads .

Pushkintak described the principles of classic translation:

ʼʼIn translated books published in the last century, it is impossible to read a single preface where there would not be an inevitable phrase: we thought to please the public, and at the same time do a service to our author, excluding from his book passages that could offend the educated taste of French reader'.

The transition to the opposite attitude towards translation (romantic), which occurred at the turn of the century, was characterized by Pushkin as follows:

ʼʼThey began to suspect that ᴦ. Letourneur could have mistakenly judged Shakespeare and did not act very wisely when he transported Hamlet in his own way, Romeo and Lear. They began to demand from translators more fidelity and less sensitivity and zeal towards the public - they wanted to see Dante, Shakespeare and Cervantes in their own form, in their folk clothes.

In 1748 A.P. Sumarokov published a drama called ʼʼHamletʼʼ At the same time, the drama by A.P. Sumarokova was not a translation either in our or in the then sense of the word. Sumarokov was even offended when Trediakovsky said that he had translated Shakespeare’s tragedy, but gave him an angry rebuke in print : “My Hamlet,” he says (ᴛ.ᴇ. Trediakovsky), I don’t know from whom he heard it, translated from the French prose of the English Shakespearean tragedy, in which he was very mistaken. My Hamlet, except for the monologue at the end of the third act and Claudius falling to his knees, barely, barely resembles a Shakespearean tragedy. And it is true. This alteration is built according to the canons of classicism; its theme is the struggle for the throne, and at its core lies the conflict of love and duty. At the same time, it was possible to treat the translated author in any way, if the alterations improved it. The classic translator treated with care only this author, who, according to his concepts, himself was approaching the ideal. But Shakespeare was, according to Sumarokov, ʼʼ English tragedian and comedian, in whom there is a lot of very thin and extremely good ʼʼ. And he remade this “bad” into “good”.

Russian translations of the 18th century are characterized by numerous cases of replacing foreign names and everyday details of the original with Russian names and details of native life, changing the entire setting of the action, that is, transferring the action into Russian reality. This practice was called ʼʼinclination to our moralsʼʼ. Examples of “inclination to our morals” can easily be found in the translations of many writers of that time, in particular, Gabriel Romanovich Derzhavin . So in translation Horace ʼʼIn Praise of Rural Lifeʼʼ he creates a purely Russian atmosphere. The reader encounters here both a mention of a “pot of hot, good cabbage soup,” and a purely Russian reality, “Peter’s Day.” That is, in essence, what happens erasing the differences between translation and one's own creativity. This form of transferring a work of foreign literature was a natural phenomenon for that time, due to the desire of translators to master the translated originals as actively as possible, to make them so personal that their foreign origin was not felt in the translations.

What attracts attention, first of all, are the translator’s numerous and detailed adjectives. If Dickens says: “The darkest days are too good for such a witch,” then Vvedensky instead he writes: “As for the water bastard, it is known to be swarming in the Peruvian mines, where you should go for it on the first ship with a bombazine flag.” Vvedensky inserted into the text not only individual tirades and paragraphs. He once announced his translation of “Dombey and Son”: “ This elegant translation contains entire pages that belong solely to my pen. ʼʼ. In his translation of “David Copperfield,” he composed the end of the second chapter, the beginning of the sixth chapter, etc. Another characteristic feature of Vvedensky’s creative method was decoration. If Dickens writes “I kissed her!”, then Vvedensky writes: “I imprinted a kiss on her cherry lips.” Even English word with the meaning ʼʼhouseʼʼ Vvedensky conveys in his own way: ʼʼOur family, the concentrated point of my childhood impressionsʼʼ. Vvedensky justified his translation method with the theory he created. The essence of the theory is essentially that the translator has every right to add adverbs to his translation, if his pen is “tuned” in the same way as the pen of the novelist himself. Based on this, Irinarch Vvedensky saw in his translations an “artistic recreation of the writer.” In an article published in 1851 in Otechestvennye zapiski, I. Vvedensky writes that “...When artistically recreating a writer, a gifted translator first and foremost pays attention to the spirit of this writer, the essence of his ideas and then to the appropriate way of expressing these ideas. When planning to translate, you must read your author, think about him, live by his ideas, think with his mind, feel with his heart and for the time being abandon your individual way of thinking ʼʼ

A characteristic feature of romanticism is extreme dissatisfaction with reality, contrasting it with a beautiful dream. Inner world Romantics proclaimed a person, his feelings, and creative imagination as genuine values, as opposed to material values. Distinctive feature Romantic creativity is the author’s clearly expressed attitude towards everything that is depicted in the work. Romantics were powerfully attracted to fantasy, folk legends, and folklore.

Posted on ref.rf

They were attracted by distant countries and past historical eras, the beautiful and majestic world of nature. Romantic heroes always in conflict with society. Οʜᴎ - exiles, wanderers. Lonely, disillusioned, the heroes challenge an unjust society and turn into rebels, rebels.

The problem of the existence of a realistic translation: what we have now, or get used to the text, close the book and write again, on behalf of the author.

The concept of the usefulness of translation Focused mainly on written translation of literary texts. Its exponents are pre-war Soviet philologists: A. Fedorov, K. Chukovsky, N. Gumilyov. The emergence of this concept is associated with the rise of structuralism in linguistics and the desire to describe language through itself without referring to extra-linguistic reality. Hence, the main idea of this theory is the extreme importance of an exhaustive transfer of content using equivalent means. Expression expressed by metaphor must be conveyed by metaphor. Translation as a linguistic exercise carried out according to certain rules. In this concept, all text units were divided into meaningful (it is unclear what content is meant!) and functional (it is overlooked that larger parts of the text can perform a certain function). And all these units must be transferred! A significant improvement of this theory was the later appeared principle of a rank hierarchy of selected components, which made it possible to identify “empty” and “variable” elements of content that can be sacrificed.

The concept of dynamic or functional equivalence (Yu. Naida, A.D. Schweitzer). Within the framework of this concept, equivalence is usually called the similarity of the intellectual and aesthetic reactions of the half-parts of the original and the translation. The translator's task is to identify the functional dominant of the translated text and preserve it in the original text. Among the basic functions of the text, which differ in their installation on one or another component speech act͵ stand out (R. Jacobson’s typology)

denotative,

expressive (per sender),

poetic (to choose the form of communication)

metalinguistic (on code, play on words)

contact-establishing (speech act for contact between communicants)

conative / volitional (per recipient)

Disadvantages: the term reaction is not defined, there are no types of reactions. In this theory, for the first time, a translator is perceived not just as a person who knows two languages, but also as a specialist in communication and culture of the respective countries. He can make linguistic-ethnic amendments in order to equalize the reactions of recipients and overcome linguistic-ethnic differences. In cases where this discrepant information is part of the content of the text, something has to be sacrificed.

SKOPOS is a universal equivalence model. SKOPOS is the goal, the goal of the translator’s activity. After all, translation is a practical activity, and any activity has a goal. If the goal pursued by the translator is not achieved, then all the work has been done in vain. The translator, who is the focus of this concept, is perceived as a person whose goal of practical activity should be anything from pleasing the boss to misleading. The success of a translation is determined by it adequacy, ᴛ.ᴇ. right choice translation method. Correct means leading to achieving the goal. The term equivalence is used to denote the properties of the result of translation activity - the text. Although it is generally understood as a functional correspondence of the PT to the original, it is by no means the goal of translation.

Neo-hermeneutic understanding of translation– translation as a means of understanding the source text through correlation with another language. Translation = understanding. Each translation is an individual reading of the original. In this concept, the problems of choosing a translation option are not so important.

§ 3. Types and levels of equivalence.

The previously discussed historical approaches to the definition of a “good” translation, from which the corresponding various concepts of equivalence were derived, presented equivalence as an undifferentiated concept. Meanwhile, V. Koller notes that the undifferentiated requirement of equivalence is meaningless, because It is unclear in what respect (and at what level, what properties of the original (invariant) should be preserved in translation?) PT should be equivalent to IT, because the text is a multifunctional and multidimensional phenomenon. He identifies 5 types of equivalence:

¨ denotative or meaningful, in which the substantive content of the text is invariant;

¨ connotative or stylistic, in which the connotative meaning of the original units is preserved by choosing the appropriate synonym;

¨ textual-normative, also called stylistic, in which the genre characteristics of the text are conveyed, the features of the corresponding language and speech norm.

¨ formal, used in the translation of puns, individualisms and other artistic and aesthetic features of the text.

¨ pragmatic or communicative, characterized by taking into account the attitude towards the recipient of the text.

These five types of equivalence define a certain “scale of values” with which the translator operates. At the same time, he has to re-establish the hierarchy of these values every time for each new text and for each individual fragment of the text. This approach to introducing the concept of equivalence has been criticized for violating the rules of logical subcategorization. Indeed, its constituent types of equivalence intersect (houses are divided into old and multi-storey). Connotative and formal components of content include integral part into the pragmatics of the text. IN modern theory translation, however, asserts the paramount importance of communicative-pragmatic equivalence, because It is precisely this that defines the relations between other types of equivalence. This requirement is consistent with the concept of a functional invariant proposed by A.D. Schweitzer.

If Koller places his types of equivalence in one plane, then V.N. Commissioners builds a certain hierarchy of equivalence levels based on the degree of semantic commonality between IT and PT. This system has been repeatedly criticized for its inconsistency and lack of universality, but, nevertheless, the very principle of such ranking of translations is interesting. His system also distinguishes 5, but not types, but levels, and at each subsequent level the existence of equivalence of the previous level is assumed. Below are those elements of content that are consistently stored at five levels allocated to them:

1. purpose of communication

2. identification of the situation

3. "way of describing the situation"

4. The meaning of syntactic structures

5. meaning of verbal signs (lexemes)

At the fifth level, it is assumed that all basic parts of the original content are preserved. The inconsistency of this system is that between the 3rd and 4th, as well as the 4th and 5th, there is not a different degree of semantic commonality, but a different form of organization of content - syntactic and lexical, respectively. See more detailed account:

Equivalence of translation when conveying the functional and situational content of the original

Taking into account the dependence on what part of the content is transmitted in translation to ensure interlingual communication, levels (types) of equivalence are distinguished. Any text has a communicative function (communicates facts, expresses emotions, requires a Receptor reaction). This determines x-r messages its linguistic design. The purpose of communication (the part of the text indicating its function) represents the “derived” meaning of the utterance, which the Receptor must reveal.

Equivalence first type

(for which the content is communicated) is to preserve that part of the content that conveys the purpose (p.

Posted on ref.rf

52).

That's a pretty thing to say. - I would be ashamed! (Disturbance)

This type of equivalence is characterized by

· incomparability of lexical composition and syntactic organization

· inability to connect the vocabulary and structure of the original with relations of semantic paraphrasing or syntactic transformation

lack of real and direct logical connections between messages

· least general content

It is used when more detailed reproduction is not possible or when it may lead the receptor to incorrect conclusions.

A rolling stone gathers no moss. It’s not even clear whether this is good or bad. Whoever does not sit still will not make any good.

In the second type (what is reported) the general part of the content of the original conveys the purpose of communication and reflects the same extra-linguistic situation. An indication of the same situation is accompanied by significant structural and semantic discrepancies. The same situation can be described through various inherent features. It is necessary to distinguish between the fact of indicating a situation and the method of describing it (part of the content indicating its signs). The nature of the reflection of selected features and the internal organization of information about them constitutes the logical structure of the message. At the root of the description of the situation “some object is lying on the table” there are the concepts of state, perception, active action. (The night is almost over - Dawn is coming; He is well preserved - He looks younger than his age). The second type is characterized by identification of content while changing the method of its description. The basis is the universal nature of the relationship between language and extralinguistic reality.

He answered the phone - He picked up the phone.

Every language has preferred ways of describing certain situations. The use of this type is associated with the presence of a traditional way of describing situations (warning notices). Different situations may receive special meaning within the culture of a particular group.

Third type (as reported in the original):

London saw a cold winter last year. - Last year the winter in London was cold.

Peculiarities

1. Lack of parallelism of lexical composition and syntactic structure

2. the impossibility of connecting structures with syntactic transformation relations

3. maintaining the goal and identifying the same situation

4. saving general concepts, with the help of which the situation is described, ways of describing the situation

There may be a complete coincidence of the structure of the message and the use of a synonymous structure. Varies:

· degree of detail in the description (in Russian translations there is greater explicitness).

· method of combining the described features (limiting the compatibility of individual concepts)

· direction of relationships between features (conversion paraphrasing)

· distribution of individual features (possibility of moving features in adjacent messages)

One of the main tasks of the translator is to convey the content of the original as completely as possible, and, as a rule, the actual commonality of the content of the original and the translation is very significant.

It is necessary to distinguish between potentially achievable equivalence, which is understood as the maximum commonality of the content of two multilingual texts, allowed by the differences in the languages in which these texts are created, and translation equivalence - the real semantic similarity of the original texts and the translation, achieved by the translator in the translation process. The limit of translation equivalence is the maximum possible (linguistic) degree of preservation of the content of the original during translation, but in each separate translation semantic closeness to the original to varying degrees and different ways is approaching maximum.

The concept of dynamic equivalence was introduced into linguistics by the American scientist Yu. Naida.

Typically, the equivalence of a translation is established by comparing the source text with the target text. Yu. Naida suggests comparing the reactions of the recipient of the translated text and the recipient of the text in the source language (i.e., the reaction of the one who receives the message through a translator and the one who receives the text directly from a native speaker of the source language). If these reactions in their essential features (both intellectually and emotionally) are equivalent to each other, then the translation text is recognized as equivalent to the source text. It should be emphasized that the equivalence of reactions means their similarity, but not identity, which, obviously, is unattainable due to ethnolinguistic, national-cultural differences between representatives of different linguistic communities.

The concept of dynamic equivalence, in principle, corresponds to the concept of functional equivalence put forward by the Soviet linguist A.D. Schweitzer: “When translating the original message into another language, the translator compares the extra-linguistic reaction to the translated message on the part of its recipient with the reaction to the original message of the recipient who perceives it in the original language.”

Obviously, the problem of achieving an equivalent reaction in the recipient of the translation is most directly related to the problem of transmitting the content of the source text. This necessitates the need to clarify what elements it consists of. HELL. Schweitzer identifies four such elements:

Denotative (i.e., subject-logical) meaning associated with the designation of certain subject situations;

Syntactic meaning, determined by the nature of the syntactic connections between the elements of the statement, i.e., its syntactic structure;

Connotative meaning, i.e. co-meaning determined by the functional-stylistic and expressive coloring of a linguistic expression;

Pragmatic meaning, determined by the relationship between the linguistic expression and the participants in the communicative act (i.e., that subjective attitude to linguistic signs, to the text, which inevitably arises among people who use language in the process of communication).

An important place in the concept of A.D. Schweitzer is occupied by the concept of communicative attitude and function of a speech work. The communicative attitude is determined by the goal pursued by the author of the statement. “This goal can be a simple communication of facts, the desire to convince the interlocutor, induce him to take certain actions, etc. The communicative attitude determines both the choice of certain linguistic means and their relative weight within the framework of a particular statement.

Considering a speech act from the angle of its communicative setting, we can identify a number of functional characteristics in it, the consideration of which is of paramount importance for the translation process.” To describe these characteristics, A. D. Schweitzer uses the classification of speech functions created by R. Jacobson:

1) “referential” or “denotative function” – description of subject situations;

2) “expressive function”, reflecting the speaker’s attitude to the utterance;

3) “poetic function”, focusing the attention of participants in a speech act on the form of a speech utterance (i.e., cases when the linguistic form of an utterance becomes communicatively significant);

4) “metalinguistic function” (when the rank of semantic elements is acquired by certain properties of a given language code; for example, when we are dealing with puns);

5) “phatic function” associated with establishing and maintaining contact between communicants.

As a rule, several functions are presented in a speech work, and the role of these functions is not the same. Elements of language that embody a dominant function are called functional dominant. From one speech work to another, from text to text, functions and, accordingly, functional dominants change. Based on this, translation is seen as a process of finding a solution that meets a specific set of varying functional criteria.

The study of the specifics of oral translation is carried out in three main areas. The first aspect of the study deals with the factors influencing the translator's extraction of information contained in the original. Interpretation is translation oral speech in a foreign language, the perception of oral speech is characterized by short-term, disposable and discrete nature, and therefore the extraction of information in the translation process is carried out differently than in the visual perception of the text. The completeness of understanding depends on the rhythm, pausing (the number and duration of pauses), and the pace of speech; information is extracted in the form of separate portions as the chain of linguistic units unfolds in the speaker’s speech; perception is carried out on the basis of “semantic reference points.” The translator predicts the subsequent content of the text based on already perceived “quanta” of information, clarifying his forecast in the process of further perception, which involves the accumulation and retention of previous information in memory. The theory of oral translation describes the psycholinguistic features and linguistic prerequisites of probabilistic forecasting in translation, its dependence on the relative semantic independence of minimal speech segments in different languages, as well as the nature of information loss during auditory perception of significant segments of speech. Factors that compensate for such losses are also described: knowledge of the subject and context of speech, which allows one to guess the content of what was missed, intonation, emotional coloring speeches, etc.

The second aspect of studying oral translation is related to considering it as a special type of speech in the TL. The theory of oral translation describes the specifics of the translator’s oral speech, which differs from ordinary “non-translation” speech. Existence distinctive features is determined by the fact that the translator’s speech is focused on the original and is formed in the translation process. During simultaneous translation, the speaking process proceeds parallel to the listening process (perception of the speaker’s speech), although part of the translation is “spoken out” during pauses in the Source’s speech. Important aspect The linguistic description of simultaneous translation consists in identifying the size (duration) of the minimum interval between the beginning of the generation of the original segment and the beginning of the translation of this segment. The size of such an interval is determined by two series of linguistic factors. Firstly, it depends on the structural features of the foreign language, which determine the length of the speech segment within which the ambiguity of its constituent units is removed. For many languages, such a segment most often includes the structural basis of the SPO sentence (subject - predicate-object) and, first of all, the verb-predicate. Often the translator is forced to delay the beginning of the translation, waiting for the appearance of a verb in the speaker’s utterance. Secondly, the size of the lag interval also depends on some features of the structure of the TL, which determine the degree of dependence of the form of the initial elements of the utterance on its subsequent elements. For example, when translating to English language the beginning of the Russian sentence “Friendship with Soviet Union... (we highly appreciate)" the translator would have to wait for the Source to pronounce the subject and predicate before he could start translating: We highly appreciate our friendship... At the same time, translating the same sentence into German, he could start translating after the very first words: Die Freundschaft mit der Sowjetunion... The size of the lag interval is also influenced by the existence in the TL of synonymous statements that differ in structure. Instead of waiting for a subject and predicate to appear in a Russian utterance, an English translator could immediately translate the beginning of the sentence as The friendship with the Soviet Union..., expecting to be able to use a different structure in the translation, for example: ...is of great value to us.

Within the framework of the special theory of oral translation, a number of other features of the translator’s speech are noted. This includes slower articulation associated with so-called hesitational pauses, fluctuations in the choice of options, leading to a sharp increase (3-4 times) in the lag interval before erroneous options, as well as the total duration of pauses in relation to the pure sound of speech. The translator's speech is less rhythmic, the simultaneous translator often speaks at an increased pace, trying to quickly “speak out” what has already been understood, and with consecutive interpretation, the rate of speech decreases significantly, since the translator understands his recording, restoring the content of the original in his memory. Particular attention in the theory of interpreting is paid to the regulatory requirements for the translator’s speech, the implementation of which in extreme conditions simultaneous and consecutive translation requires special efforts: ensuring clear articulation, uniform rhythm, correct placement of accents, mandatory semantic and structural completeness of phrases and other elements of the “presentation” of the translation, ensuring its full perception by listeners. The central aspect of studying oral translation is considering it as a special type of translation, that is, in contrast to written translation. Here, the special theory of oral translation reveals both quantitative and qualitative features. In simultaneous translation, the volume (number of words) of the translation text depends on the length of the translated speech segments. When transferring short phrases the number of words in simultaneous translation is, on average, greater than in written translation due to more elements of description, explanation. When translating long phrases, these values are leveled out, and when translating paragraphs and larger sections of text, simultaneous translation turns out to be less wordy, both due to the deliberate compression of the text during the translation process, and due to a certain number of omissions. A reduction in the volume of the translation text compared to a written translation of the same original is noted in all cases and in consecutive translation. The number of omissions increases with the speaker's speech rate. Therefore, the theory of interpreting pays special attention to the causes, methods and limits of speech compression. The need for compression is determined by the fact that the conditions of oral (especially simultaneous) translation do not always allow the content of the original to be conveyed as completely as in written translation. Firstly, with the speaker’s fast pace of speech, it is difficult for the translator to have time to pronounce full text translation. Secondly, the speed of the speech and thinking process of each translator has its own limits, and he often cannot speak as quickly as a speaker. Thirdly, the hasty utterance of speech utterances often affects their correctness and completeness, as a result of which their perception by the Translation Receptor and the entire process of interlingual communication are disrupted. Speech compression during interpreting is far from an easy task. This is not just about omitting part of the original, but about compressing the translated message in such a way that all important elements sense. Compression becomes possible due to the information redundancy of speech. A statement often contains elements of information that duplicate each other, and during translation some of them can be omitted while maintaining the content of the message. For example, if the translator completely translated the question “When will this plan begin?” and he has to translate the answer “Implementation of this plan will begin in 1990,” then he can condense it to “in the nineties.” A statement may sometimes contain side information (politeness formulas, random remarks, deviations from the topic), the omission of which will not interfere with the implementation of the main task of communication. In some cases, the communication situation makes it unnecessary to convey some part of the information in verbal form and thus allows for a reduction of information during translation.

Message compression during translation is a variable value. It depends on the rate of speech of the speaker and on the relationship between the structures of the FL and TL. The theory of oral translation describes speech compression techniques for each pair of languages using both structural and semantic transformations. The most typical methods of compression are synonymous replacements of phrases and sentences with shorter words, phrases and sentences, replacing the full name of an organization, state, etc. with an abbreviation or abbreviated name (The United Nations - UN), replacing a combination of a verb with a verbal noun with a single verb , denoting the same action, process or state as the noun being replaced (to render assistance - to help), omission of connecting elements in the phrase (the policy pursued by the United States - US policy), replacement subordinate clause participial or prepositional phrase (When I met him for the first time - at the first meeting with him), etc. When the speaker speaks quickly, the use of various methods of speech compression can reduce the translation text by 25 - 30% compared to a written translation of the same original.

An important part of the theory of interpreting is the study of the nature of equivalence achieved in various types such a translation. As already indicated, in interpreting there is sometimes a loss of information compared to the level of equivalence established in written translation. The observed deviations are reduced to omissions, additions or erroneous substitutions of information contained in the original. Each type of deviation includes smaller categories that vary in the importance of the information not conveyed or added. Passes include:

1) omission of an unimportant individual word, mainly an epithet;

2) omission of more important and larger units, associated with the translator’s misunderstanding of part of the text;

3) omission of part of the text due to restructuring of the text structure during translation;

4) omission of a significant part of the text due to a lag in the translation from the speaker’s speech. Additions are classified according to the nature of the added redundant elements: individual qualifiers, additional explanations, clarifying connections between statements, etc.

And finally, errors are divided according to the degree of importance: a small error in the translation of a single word, a gross semantic error in the translation of a single word, a small error due to a minor change in structure, a gross semantic error in the case of a significant change in structure, etc. When assessing the quality of oral translation takes into account the specifics of the oral form of communication: with direct contact between communicants, establishing equivalence at a lower level in some cases does not interfere with their mutual understanding, which to a certain extent compensates for the loss of information in the process of oral translation. These two methods of classifying translations (by the nature of the translated text and by the form of perception of the original and creation of the translation text) are based on different principles, and the types of translation identified in each of them, naturally, do not coincide. Theoretically, any type of text can be translated either orally or in writing. In practice, however, the specifics of oral translation impose certain restrictions on the degree of complexity and volume of translated texts, which in a certain respect is also related to their functional and genre characteristics. Works of fiction, in general, are not translated orally, although individual quotations from such works may be given in oral presentations and translated simultaneously or sequentially. Providing artistic and aesthetic impact in oral translation with its rigid temporal framework is very challenging task, especially if poetic works are quoted, the translation of which is unknown to the translator in advance. Large-scale works of informative genres are not translated orally, since the duration of oral translation is limited not only by translation capabilities, but also by the short duration of oral communication in general: it is physically impossible to speak, listen and memorize continuously over a long period of time.

4. The concept of dynamic (functional) equivalence. The concept of dynamic equivalence, which was first identified by Eugene Naida, is similar to the concept of functional equivalence by the Russian researcher A.D. Schweitzer. We are talking about the coincidence of the reaction of the recipient of the source text and a native speaker of one language with the reaction of the recipient of the translation text, a native speaker of another language. According to A.D. Schweitz

The concept of equivalence, both from a functional and substantive point of view, is considered differently by translation theorists of the twentieth century, however, from our point of view, almost all the variety of approaches can be reduced to two main types - equivalence tied to linguistic units, and equivalence not tied to linguistic units.

What are the requirements for the equivalence of two texts - the original text and the text of its translation? According to L.K. Latyshev, there are three such requirements:

Both texts must have (relatively equal communicative and functional properties (they must “behave” in relatively the same way, respectively, in the sphere of native speakers of the source language and in the sphere of native speakers of the target language);

To the extent permissible under the first condition, both texts should be as similar as possible to each other in semantic-structural terms; AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

With all “compensating” deviations between both texts, semantic-structural discrepancies that are not permissible in translation should not arise.

L.K. Latyshev believes that the equivalence of the source text and the text of its translation is achieved (that is, equality of communicative effects is achieved) when the differences in the linguistic-ethnic communicative competence of the two recipients are neutralized. At the same time, the task is not to ensure equality of communicative situations of the recipients of the source and translated text or the task of equalizing communicative competencies (using preliminary comments or notes to the text), it is enough to “create (relatively) equivalent linguistic-ethnic prerequisites for the perception of the message (in its multilingual variants) and reaction on him.

L.K. Latyshev distinguishes between small-scale and large-scale equivalence, saying that characteristic translation - a frequently occurring discrepancy between the equivalence of individual sections of the source text and the target text and the equivalence of these tests as a whole. The point here is that translation equivalence must ultimately be established at the level of two texts, and large-scale equivalence allows for the sacrifice of small-scale equivalence.

So, we have looked at various aspects of equivalence. It can be argued that this is a multi-valued concept in translation theory. Each time we must distinguish whether we are talking about substantive or functional equivalence, and what level of equivalence we mean.

L.K. Latyshev identifies four types of translation equivalence. Let us briefly describe these types.

The equivalence of translations of the first type consists in preserving only that part of the content of the original that constitutes the purpose of communication:

The purpose of communication is the most general part of the content of an utterance, characteristic of the utterance as a whole and determining its role in the communicative act. The relationship between originals and translations of this type is characterized by:

The absence of real or direct logical connections between the messages in the original and the translation, which would allow us to assert that in both cases “the same thing is reported”;

The least common content between the original and the translation compared to all other translations considered equivalent.

Thus, in this type of equivalence, the translation seems to say “not at all the same” and “not at all what” is said in the original. This conclusion is valid for the entire message as a whole, even if one or two words in the original have direct or indirect correspondence in the translation.

Translations at this level of equivalence are performed both in cases where a more detailed reproduction of the content is impossible, and also when such reproduction will lead the translation receptor to incorrect conclusions, cause it to have completely different associations than the original receptor, and thereby interfere with correct transmission communication goals.

The second type of equivalence is represented by translations, the semantic proximity of which to the original is also not based on the common meaning of the linguistic means used.

In equated multilingual utterances, most of the words and syntactic structures of the original do not find a direct correspondence in the translation text. At the same time, it can be argued that between the originals and translations of this group there is a greater commonality of content than with the equivalence of the first type.

The relationship between originals and translations of this type is characterized by:

Incomparability of lexical composition and syntactic organization;

The inability to connect the vocabulary and structure of the original and translation through relations of semantic paraphrasing or syntactic transformation;

Preservation of the purpose of communication in translation, since preservation of the dominant function of the utterance is a prerequisite for equivalence;

Preservation in translation of an indication of the same situation, which is proven by the existence of a direct real or logical connection between multilingual messages, which allows us to assert that in both cases “the same thing is reported.”

The third type of equivalence can be characterized as follows:

Lack of parallelism of lexical composition and syntactic structure;

The inability to connect the structures of the original and the translation with relations of syntactic transformation;

Preservation in translation of the purpose of communication and identification of the same situation as in the original;

Preservation in translation of general concepts with the help of which the situation is described in the original, i.e. preservation of that part of the content of the source text, which is called “the way of describing the situation.”

In the three types of equivalence described above, the commonality of the content of the original and the translation was the preservation of the basic elements of the content of the text. As a unit speech communication, the text is always characterized by communicative functionality, situational orientation and selectivity in the way of describing the situation. These features are also preserved in the minimum unit of text - the statement. In other words, the content of any statement expresses some purpose of communication through a description of some situation, carried out in a certain way (by selecting some features of this situation). In the first type of equivalence, only the first of the specified parts of the original content (the purpose of communication) is retained in the translation, in the second type - the first and second (the purpose of communication and a description of the situation), in the third - all three parts (the purpose of communication, a description of the situation and the method of describing it ).

The concept of translation equivalence

The term “equivalence” has a complex history. Once upon a time it denoted the correspondence of the sum of the meanings of the words of the source text to the sum of the meanings of the words of the translated text.

In modern translation theory, it denotes the correspondence of the translation text to the original text. Equivalence has an objective linguistic basis, and therefore it is sometimes called linguistic in order to limit the possible interpretations of the term related to the literary approach to translation. The concept of translation equivalence includes an idea of the translation result that is as close as possible to the original, and an idea of the means to achieve this result. In the history of translation, various concepts of equivalence have evolved. Some of them are still relevant today. The modern scientific view of equivalence has gotten rid of the previous metaphysical idea that it is possible to achieve a translation that is an exact copy of the original.

This was consistent with the metaphysical view of the text as arithmetic sum elements, each of which individually could be reproduced in translation. That is why doubts arose from time to time about the possibility of translation in general - whenever the development of knowledge about language revealed more complex patterns (linguo-ethnic specificity; the nature of the sign; the psychology of speech perception, etc.). It turned out that neither one hundred percent transmission of information nor one hundred percent reproduction of the unity of the text through translation is possible. And this does not mean that translation is impossible at all, but only that translation is not absolute identity with the original. Thus, translation equivalence involves achieving maximum similarity; the theory of equivalence is a theory of the possible, based on the maximum competence of the translator.

Equivalence is a complex concept; To describe it, researchers use a whole palette of parameters. V. Koller, for example, names 5 factors that set certain conditions for achieving equivalence:

1. Extra-linguistic conceptual content transmitted through the text - and denotative equivalence oriented towards it.

2. Connotations conveyed by the text, determined by stylistic, sociolectal, geographical factors, and connotative equivalence oriented towards them.

3. Text and language norms and text-normative (normative-conventional) equivalence oriented towards them.

4. The recipient (reader) for whom the translation should be “tuned” - pragmatic equivalence.

All these factors, one way or another, are reflected in various concepts of equivalence.

Historical concepts and universal models of translation equivalence

text translation equivalence neohermeneutic

Man has always strived for the most complete correspondence of the translation to the original. This correspondence was understood in different ways, but there was always a theoretical basis for it. This base has become truly scientific in our days, but the previous generalized ideas were based on the real text and its translation, they had their integrity, harmony and, not by chance, at least in part, are still relevant today.

The concept of formal compliance. This is one of the most ancient concepts of equivalence. “One of”, since it can be assumed that the first spontaneously arising principles of oral translation, from which it all began, were still different from it.

The concept of formal correspondence emerged as a basis for the transmission of written text. It is important for us to imagine how people treated the text at that time, what role it played for them. People had a new faith - Christianity, and with it came a sacred text, one of the embodiments of this faith - the Bible. And not only the sacred written text entered people’s lives along with Christianity, but also writing in general, which actually arose among European peoples as a tool for the written translation of the Bible. Until this moment, people did not have a written text of such significance. The main sacred text and the accompanying texts that appeared later were perceived as a hypostasis of God, and the idea of the iconic character of each sign of the original text was quite natural. The idea of a random connection between a sign of a language code and an object of reality was then unthinkable. A natural consequence of the idea of the iconic nature of a linguistic sign was the concept of word-by-word translation, or formal correspondence, since the word - the main and only unit of translation according to this concept - had formal characteristics, and this led to the transfer of translation along with the meaning of the word structural components, formalizing it in the text. Truly, in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was God. According to the concept of formal correspondence from the written text to the translation text linearly, word by word all components of content and form are transmitted to the maximum extent. Such a translation text turned out to be overloaded with information, primarily intralingual, which often blocked cognitive information and, accordingly, the denotative and significative components of the content.

The concept of formal correspondence was cultivated in monasteries and, with some amendments, has survived to this day as a traditional method of translating religious books.

We see elements of the concept of formal correspondence in the translation principles of the ACADEMIA publishing house - they are associated with a scientific, philological approach to the original text, with the initial stage of its preparation for translation. Then, in the translation principles of Soviet translators of the 1930-1950s, the formal principle turned into dogma and was of a forced nature.

Many translations of this time were not perceived by the reader and are now forgotten, since the abundance of intralingual information caused the greatest damage to the aesthetic information of the original, and it was almost completely blocked.

In modern scientific philological research, word-by-word translation when analyzing a foreign language text is a productive research technique.

The concept of normative-substantive compliance. Since ancient times, a different approach to translation has emerged. It was associated with those texts that people used every day and where the language code implemented its main function - the function of transmitting information. This concept of equivalence has two main principles: 1) the most complete transfer of content; 2) compliance with the norms of the target language.

However, this concept received its final form when people began to need a different translation of the Bible. It developed gradually, and the moment came when sacred awe of the original was combined with the desire to understand the meaning of the Word contained in it; man wanted to know God independently, without intermediaries, through Holy Bible. It was then that the concept of formal compliance, which ceased to satisfy people, receded into the background, and the concept of normative-substantive compliance spread amazingly quickly.

This concept ensures the equivalence of not only written but also oral translation.

Concept of aesthetic conformity. So we can outline the principles of approaching the source text as a kind of material, the basis for creating through translation perfect text, corresponding to some extra-textual aesthetic ideal. Translation without relying on the objective parameters of the source text led to complete blocking of all types of information, did not reflect the content of the original, and as a result, the translation was dominated by a fairly stable composition of aesthetic information, the same for all texts and serving as an illustration of the principles of ideal aesthetics.

The concept of the usefulness of translation. The concept of the usefulness of translation was formed throughout the 19th-20th centuries. on the translation of written literary text. The translation of the Romantic era, focusing on the transfer of national identity, was, in fact, the first, albeit incomplete, version of this concept. Already in the middle of the 20th century, the concept acquired its final form. Its authors are A.V. Fedorov and Ya.I. Retzker, based on the experience of literary translation, actually set themselves the task of getting rid of extra-textual aesthetic attitudes and identifying objective criteria for translation equivalence. The following criteria were put forward: 1) comprehensive transmission of content; 2) transfer of content by equivalent means. Moreover, the equivalence of means does not mean their formal similarity, but the equivalence of their functions, i.e. equivalence expressive means in the original and translation. Translation texts that meet these two criteria can be considered complete or adequate.

The concept of dynamic equivalence. The concept of dynamic equivalence was formulated in the late 1950s. American scientist Eugene Naida. Yu. Naida proposes to establish equivalence not by comparing the original text and the target text, but by comparing the reaction of the recipient of the source text in the native language and the reaction of the recipient of the same text through the translator - in the target language. If these reactions coincide intellectually and emotionally, then the translation is equivalent to the original. Equivalence of reactions means their similarity, not identity.

Currently, the concept of dynamic (functional) equivalence does not have clear parameters for measuring and comparing reactions. The term “reaction” itself requires clarification. Of course, we are not talking about individual human reactions, but about certain averaged reactions typical for a speaker of a given language - constructs. They are abstract and predictive in nature. They do not include personal reactions at the interpreter level. The object of comparison is linguistic-ethnic reactions (LER). Translator, having a high professional competence, acts as an expert on the average (linguo-ethnic) reactions of the linguistic community.

For example, if a communicator uses a phrase that sounds quite normal in his language, but sounds rude in the language of a foreign speaker, he makes an amendment. A Russian buyer says to the seller: “Show me the coat!”, “I want to buy a suit!”, and this is normal for Russian etiquette. In this situation, the German language includes more means of politeness: “Zeigen Sie mir bitte den Mantel!”, “Ich möchte mir einen Anzug kaufen!”

Concepts of equivalence developed in different time and reflecting different historically explainable human approaches to the text, at present, having been refined on the basis of modern linguistic concepts, primarily on the basis of the theory of text and the theory of linguistic communication, they make it possible to develop the fundamentals of a methodology for translating any text.

Universal model "skopos". This concept is primarily aimed at explaining the multiplicity of previous “practical” concepts and those seemingly paradoxical results of translation that did not fit into any of the concepts, and yet existed and were requested by society (for example, translation-retelling for children, or poetic translation of the New Testament). The authors of the concept were German translation theorists Katharina Reis and Hans Fermeer in the early 1980s.

OS new concept is the concept of “skopos” - Greek"target". Since translation is a practical activity, it is carried out for a specific purpose. If the purpose of the translation is fulfilled, then the translation activity in this case can be considered successful. If the purpose of non-translation is fulfilled, then none of the previous equivalences will correct the failure. Let us pay attention to two features of the new concept. First: the purpose of translation is understood more broadly than the communicative task and function of the text. The purpose of translation can be not only a full transfer of the content of the original, but also disorientation of the recipient, misleading, the task of pleasing the recipient, introducing through translation a political idea alien to the original, etc. At the same time, both the translator and the customer can pursue their own goals. Second: the authors of the concept of “skopos” assign a subordinate place to the concept of equivalence in their concept, defining it as the functional correspondence of the translation text to the original text, as special case achieving the purpose of translation without ensuring its success. And the success of translation is determined by adequacy, understood by the authors as the correct choice of translation method, i.e. as a parameter of the translation process. K. Rice and H. Fermeer also note that both concepts - equivalence and adequacy - are not static. Adequacy - because the purpose of translation changes every time, and equivalence - because at different historical stages people could understand the function of the same text differently.

Thus, the universal “skopos” model turned out to be a new step in the development of theoretical views on translation; it made it possible to include into consideration those borderline cases of translation activity that had not previously been theoretically comprehended. And they were subjected only to a “taste” assessment.

Neo-hermeneutic universal model of translation. At the center of this concept is the problem of understanding and comprehension by the translator of the source text. One of the supporters of the concept, the German researcher R. Stolze, who outlined the foundations of her hermeneutic concept in the monograph “Hermeneutic Translation,” formulates it as follows: “Translation is understanding.” Consequently, each translator, focusing on the depth of his individual understanding of a given fragment of a given text, will make a translation decision that is not similar to his own decisions or the decisions of other translators in similar cases. Therefore, depending on the individual understanding, the play on words in one case will be conveyed literally, in another case it will be reproduced, but on the basis of the polysemy of a word of a different semantics, and in the third it will be completely omitted. Since each text requires individual creative understanding, all translation solutions are individual and unique. The concept of equivalence dissolves into uncertainty initial stage translation.

The concept of dynamic equivalence, which was first identified by Eugene Naida, is similar to the concept of functional equivalence by the Russian researcher A.D. Schweitzer. We are talking about the coincidence of the reaction of the recipient of the source text and a native speaker of one language with the reaction of the recipient of the translation text, a native speaker of another language. According to A.D. Schweitzer, the content that needs to be conveyed consists of four elements or four meanings: 1) denotative; 2) syntactic; 3) connotative and 4) pragmatic meaning ("determined by the relationship between the linguistic expression and the participants in the communicative act").

Equivalence levels

According to the theory of V.N. Komissarov “the equivalence of translation lies in the maximum identity of all levels of content of the original and translation texts.”

The theory of equivalence levels by V.N. Komissarov is based on the identification of five content levels in terms of the content of the original and translation:

1. level of linguistic signs;

2. level of utterance;

3. message level;

4. level of description of the situation;

5. level of communication purpose;

The original and translation units may be equivalent to each other at all five levels or only at some of them. The ultimate goal of translation is to establish the maximum degree of equivalence at each level.

In translation studies, there is often a thesis that the main determining principle of text equivalence is a communicative-functional feature, which consists of the equality of the communicative effect produced on the recipients of the original and translated texts.

However, when interpreting communicative-functional equivalence, it is argued that when creating a text in language B, the translator constructs it in such a way that the recipient in language B perceives it in the same way as the recipient in language A. In other words, ideally the translator himself should not introduce into the text of the message an element of one’s own perception, different from the perception of this message by the recipient to whom it was addressed. In fact, the perception of the translator and any of the speech recipients may not be the same due to a variety of personal, cultural and social reasons.

It is obvious that the main goal of translation is not to adjust the text to someone’s perception, but to preserve the content, functions, stylistic, communicative and artistic values of the original. And if this goal is achieved, then the perception of translation in language environment translation will be relatively equal to the perception of the original in the language environment of the original. Exaggerating the role of the communicative-functional factor in translation leads to the erosion of the internal content, the informative essence of the text itself, the original and the translation, to the replacement of the essence of the object with the reaction to it on the part of the receiving subject. It is not the text itself that becomes decisive, but its communicative function and the conditions for realizing the semantic content of the text; transmission of content by equivalent (that is, performing a function similar to the expressive function of the language means of the original) means.

Communicative-functional equivalence in modern translation studies viewed in a wide field translation pragmatics- that is, a set of factors that determine the orientation of the translation towards its recipient, in other words, the “approximation” of the translation to the recipient. A reasonable balance of approaches involves three main factors that determine translation equivalence.