P: Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov lived a bright, but short life. Unfairly accused of an anti-Soviet conspiracy, he was shot. He died in a creative upsurge, full of bright ideas, a recognized Poet, theorist of verse, and an active figure in the literary movement. For over 60 years his works were not republished, his name was kept silent. It was only in 1987 that his innocence was openly stated.

N. Gumilyov’s whole life is unusual, fascinating, and testifies to the fortitude of an amazing personality.

What are the ways to form N. Gumilyov’s extraordinary personality?

Goal: To do this, we will get acquainted with the life and creative path of the Poet and create an imaginary book on the biography and work of N. Gumilyov.

Here are her pages.

Milestones of Gumilyov's life

- Childhood. Youth and first works.

- The greatest love.

- Trips.

- Participation in World War I

- Activities after the October Revolution.

I prepared every page of an imaginary book creative Group students. The children turned to biographies, memoirs of contemporaries, critical and scientific articles. The materials they collected will be presented to you.

Your task is to write down the main facts of the life and work of N. Gumilyov.

1 page – Childhood, youth, first works (1886-1906)

Work, bend, fight!

And a light dream of dreams

Will pour in

Into imperishable features.

N. Gumilev. "Art"

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev was born on April 3, 1886 in the family of a ship's doctor in Kronstadt. There was a storm on the night of his birth. The old nanny saw a kind of hint in this, saying that the newborn would have fast paced life. She turned out to be right. Gumilyov had an unusual destiny, a poet's talent that was imitated, he loved traveling, which became part of his life. Finally, he created a literary movement - Acmeism.

In 1887 the family moved to Tsarskoye Selo, where Nikolai began to study at the Tsarskoye Selo gymnasium, then at the St. Petersburg gymnasium, and when in 1900. the family moves to Tiflis - to the Tiflis gymnasium.

Gumilyov did not have a particular passion for science either in childhood or in his youth. Since childhood, Nikolai dreamed of traveling; it was not for nothing that his favorite lecture subjects were geography and zoology. He enthusiastically indulged in playing Indians, reading Fenimore Cooper, and studying the habits of animals.

From the age of 5 he rhymed words, and as a high school student he composed poems in which the main place was given to exoticism, adventures, travel, and dreams of the unusual.

In 1903 the family returns to Tsarskoe Selo, Gumilyov brings an album of poems - imitative, romantic, sincere, which he himself highly valued and even gave to girls.

Gumilyov again visited the Tsarskoye Selo gymnasium, he became friends with the director, Innokenty Annensky, who cultivated in his students a love of literature and poetry. Gumilev will give him his first real collection of poems. The wonderful lines of a grateful student are dedicated to his memory:

I remember the days: I, timid, hasty,

Entered the high office,

Where the calm and courteous one was waiting for me,

A slightly graying poet.A dozen phrases, captivating and strange,

As if accidentally dropped,

He threw nameless people into space

Dreams - weak me...

Childhood was ending. 18 years. Gumilyov was in an uncertain state: on the one hand, he was a 7th grade student who painted the walls of his room to look like the underwater world, and on the other, he was 18 years old... And that means something.

But I myself did not feel this uncertainty, because... was busy in charge - did myself.

Contemporaries describe “a blond, self-confident young man, extremely ugly in appearance, with a sidelong glance and a lisping speech.” In your youth, with a similar appearance, it doesn’t take long to fall into an inferiority complex and bitterness. But Gumilyov set himself a goal - to become a hero who challenged the world. Naturally weak and timid, he ordered himself to become strong and decisive. And so he did. Later his character will be described as firm, arrogant, and very self-respecting. But everyone loved and recognized him. He made himself.

As a child, despite his physical weakness, he tried to dominate the game. Perhaps he began to compose poetry out of a thirst for fame.

He always seemed calm, because he considered it unworthy to show excitement.

In 1905, a modest collection of poems by N. Gumilyov entitled “The Path of the Conquistadors” was published. Gumilev is only 19 years old.

– Who are the conquistadors?

Conquistadors –

1) Spanish and Portuguese conquerors of Central South America, brutally exterminating the local population;

2) invaders.

– Read the poem “I am a conquistador in an iron shell...” In what form does he appear? lyrical hero? What can you say about him?

In the first line, the lyrical hero declares that he is a conquistador. One might say, a discoverer of new lands, he is distinguished by his activity and thirst for achievement:

Then I will create my own dream

And I will lovingly enchant you with the song of battles.

And then the hero declares that he is “an eternal brother to abysses and storms.”

– What can you say about the lyrical hero of other poems in the collection?

The hero of the poems is sometimes a proud king, sometimes a prophet, but he is always a courageous person, he strives to learn and feel a lot. The poems even sound courageous.

– N. Gumilyov managed to embody his own character in the poems of the first collection - strong, courageous. The poet and his hero strive for new impressions.

The conqueror's mask in the 1st collection is not a random image, not a tribute to youthful dreams, but a kind of symbol of the strong, arrogant a hero who challenges everyone. N. Gumilev wanted to become such a strong hero.

The poet never republished the collection. But the leader of the Symbolists, the poet V. Bryusov, gave a favorable review: The book is “only the path of the new conquistador” and that his victories and conquests are ahead, and also noted that the collection also contains several beautiful poems, truly successful images.

1906 Gumilev graduated from high school.

In 1908, Gumilyov published his second collection of poems, “Romantic Flowers.” I. Annensky, listing the merits of the book, noted the desire for exoticism: “The green book reflected not only the search for beauty, but also the beauty of the search.

And for Gumilev it was a time of searching. The first collection, “The Path of the Conquistadors,” was decadent, the second collection, “Romantic Flowers,” was symbolist. But the main thing for the poet was that he climbed one more step of self-affirmation.

Page 2 – The greatest love (1903-1906,1918).

And you left in a simple and black dress,

Looks like an ancient crucifix.

N. Gumilev

Here is an excerpt from a student’s essay, which was created based on a message on this topic.

The most remarkable pages of the life of N. S. Gumilyov.

N. Gumilyov is an amazing master of words, the founder of the literary movement Acmeism.

His biography seemed very interesting to me, and the fact that the poet was the husband of the famous Russian poetess Anna Andreevna Akhmatova became completely new to me.

On December 24, 1903, at the Tsarskoye Selo gymnasium, where young Gumilev was then studying, he met Anna Gorenko, the future poetess A. Akhmatova. This is how it happened. Nikolai Gumilyov and his brother Dmitry were buying Christmas gifts and ran into a mutual friend, Vera Tyulpanova, who was with a friend. Dmitry Gumilyov began to talk to Vera, and Nikolai remained with a light-eyed and fragile girl with black and long hair and a mysterious pallor of her face. Vera introduced them:

– My friend, Anna Gorenko, studies at our gymnasium. We live in the same house with her.

Yes, Anya, I forgot to tell you: Mitya is our captain, and Kolya writes poetry.

Nikolai looked at Anya proudly. She did not say that she writes poetry herself, but only asked:

– Could you read some of yours?

– Do you like poetry? – asked Gumilyov. – Or are you out of curiosity?

– I like them, but not all of them, only the good ones.

I am a conquistador in an iron shell,

I'm happily chasing a star

I walk through abysses and abysses

And I rest in a joyful garden.

- Well, are they good?

- Just a little unclear.

Their second meeting took place soon at the skating rink.

On Easter 1904, the Gumilevs gave a ball, and Anna Gorenko was among the invited guests. Their regular meetings began this spring. They attended evenings together at the town hall, climbed the Turkish Tower, watched Isadora Duncan's tour, attended a student evening at the Artillery Assembly, participated in a charity performance and even attended several seances, although they treated them very ironically. At one of the concerts, Gumilyov met Andrei Gorenko, Anna's brother. They became friends and loved to discuss poems by modern poets.

In 1905, Anna with her mother and brother moved to Yevpatoria. In October of the same year, Gumilyov published his first book of poems, “The Path of the Conquistadors.”

Soon Nikolai leaves for Paris and becomes a student at the Sorbonne. At the beginning of May 1907, Gumilyov went to Russia to serve his military service, but was released due to eye astigmatism. Then he went to Sevastopol. There, at Schmidt's dacha, Gorenko spent the summer.

Gumilyov proposes to Anna, but he is refused. He decides to take his own life by trying to drown, but remains alive and unharmed. The poet returns to Paris, where his friends try to distract him from his sad thoughts. Soon Andrei Gorenko arrived in Paris and, naturally, stayed with Gumilyov. There were stories about Russia, about the south, about Anna. Hope again... Gradually Nikolai's mood began to improve, and already in October, leaving Andrei in his room in the care of friends, he again went to Anna. And again a refusal... Gumilyov returned to Paris, but hid his trip even from his family. But he couldn’t get away from himself, so it was no coincidence that his new suicide attempt was poisoning. According to the story of A. N. Tolstoy, Gumilyov was found unconscious in the Bois de Boulogne. Akhmatova, having learned about this from her brother, sent Gumilev a magnanimous reassuring telegram. A spark of hope flared up again. The pain of Anna's refusals, consents and again refusals drove Nikolai into despair, but one way or another he continued to write. At the beginning of 1908, a book of poems, “Romantic Flowers,” dedicated to A. Akhmatova, was published. On April 20, Gumilev comes to see her again. And again he was refused. On August 18, 1908, the poet was enrolled as a student at the Faculty of Law. And in September he leaves for Egypt...

Upon his return, he continued his studies. And on November 26, 1909, at the European Hotel, he again proposed to A. Akhmatova and this time received consent. On April 5, 1910, Gumilyov submitted a petition to the rector of the university to allow him to marry A. Akhmatova. Permission was received on the same day, and on April 14 - permission to go on vacation abroad. On April 25, in the St. Nicholas Church in the village of Nikolskaya Slobodka, a wedding took place with the hereditary noblewoman Anna Andreevna Gorenko, who became Gumileva. But even after marriage, their love was strange and short-lived.

Page 3 – Travel (1906-1913)

I'll walk along the echoing sleepers

Think and follow

In the yellow sky, in the scarlet sky

Rail of running thread.

N. Gumilev

An excerpt from an essay based on a message on this topic.

Composition.

The most remarkable pages of N. Gumilyov's life.

And that's all life! Whirling, singing,

Seas, deserts, cities,

Flickering reflection

Lost forever.

N. Gumilev

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov is an extraordinary person with a rare destiny. This is one of greatest poets silver age. But he was also a tireless traveler who traveled to many countries, and fearless warrior, who risked his life more than once.

The poet's talent and the courage of the traveler attracted people to him and inspired respect.

Gumilyov's travels are one of the brightest pages of his life. As a child, he developed a passionate love of travel. No wonder he loved geography and zoology. Fenimore Cooper is Gumilyov's favorite writer. The boy's family moved a lot, and he had the opportunity to see other cities, another life. The Gumilevs lived first in Kronstadt, then in Tsarskoe Selo and for about 3 years in Tiflis. After graduating from the Tsarskoye Selo gymnasium in 1906. the poet leaves for Paris, where he plans to study at the Sorbonne.

The poet forever remembered his first trip to Egypt (1908). And in 1910 he reached the center of the African continent - Abyssinia. In 1913, Gumilev led an expedition of the Russian Academy of Sciences to this country. The expedition was difficult and long, but it introduced us to the morals and customs of the local residents. The impressions made made the difficulties worth it.

Gumilyov is drawn to exotic, little-studied countries, where she has to risk her life. What makes him make these trips? Contemporaries noted the youth of his soul: it was as if he had always been 16 years old. In addition, he had a great desire to understand the world. The poet understood that life is short, but there are so many interesting things in the world. But the main thing that Gumilyov brought back from his travels was a lot of impressions, themes, and images for poetry. In the collection “Romantic Flowers” Gumilev draws images of exotic animals - jaguars, lions, giraffes. And his heroes are captains, filibusters, discoverers of new lands. Even the titles of the poems are striking in the breadth of geographical names: “Lake Chad”, “Red Sea”, “Egypt”, “Sahara”, “Suez Canal”, “Sudan”, “Abyssinia”, “Madagascar”, “Zambezi”, “Niger” . Gumilyov was fond of zoology and collected stuffed exotic animals and collections of butterflies.

Page 4 – participation in World War I (1914-1918).

Nikolai Stepanovich was constantly looking for tests of character. When World War I begins, Gumilyov, despite his release, enlists as a volunteer in the Life Guards Uhlan regiment hunter, as they were called then. War is Gumilyov’s element, full of risk and adventure, like Africa. Gumilev took everything very seriously. Having achieved enlistment in the army, he improved in shooting, riding and fencing. Gumilyov served diligently and was distinguished by his courage - this is evidenced by his rapid promotion to ensign and 2 St. George's Cross– IV and III degrees, which were given only for courage. Contemporaries recalled that Gumilev was faithful in friendship, courageous in battle, even recklessly brave. But even at the front, he did not forget about creativity: he wrote, drew, and debated poetics. In 1915 The book “Quiver” was published, in which the poet included what he created at the front. In it, Gumilyov revealed his attitude to the war, speaking about its hardships, death, and the torment of the rear: “That country that could have been a paradise became a lair of fire.”

In July 1917 Gumilyov was assigned to an expeditionary force abroad and arrived in Paris. He wanted to get to the Thessaloniki front, but the allies closed it, then the Mesopotamian front.

In 1918 In London, Gumilyov prepared documents to return to Russia.

Page 5 – Creative and social activity in 1918-1921.

And I won't die in bed

With a notary and a doctor...

N. Gumilev

Upon returning to his homeland, the most productive period of Gumilyov’s life began. This is explained by the combination of the flourishing of physical strength and creative activity. Outside of Russia, Gumilyov probably would not have been able to become a master of Russian poetry, a classic of the Silver Age. Since 1918 and until his death, Gumilyov was one of the prominent figures of Russian literature.

The poet became involved in intense activity to create a new culture: he lectured at the Institute of Art History, worked on the editorial board of the publishing house “World Literature”, in a seminar of proletarian poets, and in many other areas of culture.

The poet is glad to return to his favorite work - literature. Gumilyov's poetry collections are published one after another:

1918 - “The Bonfire”, “The Porcelain Pavilion” and the poem “Mick”.

1921 – “Tent”, “Pillar of Fire”.

Gumilev also wrote prose and drama, kept a unique chronicle of poetry, studied the theory of verse, and responded to the phenomenon of art in other countries.

M. Gorky offers to become the editor of World Literature, where he began to form a poetic series. Gumilev literally united all the St. Petersburg poets around himself, created the Petrograd department of the “Union of Poets,” the House of Poets, and the House of Arts. He had no doubt that he could lead the literary life of Petrograd. N. Gumilyov creates the 3rd “Workshop of Poets”.

Gumilyov's creative and social activities made him one of the most significant literary authorities. Performances at institutes, studios, and at parties brought him wide fame and formed a wide circle of students.

The collection “Bonfire” (1918) is the most Russian in content of all Gumilyov’s books; on its pages we see Andrei Rublev and Russian nature, the poet’s childhood, a town in which “a cross is raised over the church, a symbol of clear, Fatherly power,” ice drift on the Neva.

IN last years he writes a lot of African poetry. In 1921 they will be included in the collection “Tent”. During these years, Gumilev comprehends life, teaches readers to love their native land. He saw both life and earth as endless, beckoning with their distances. Apparently, this is why he returned to his African impressions. The collection “Tent” is an example of the poet’s great interest in the life of other peoples. This is how he writes about the Niger River:

You flow like a solemn sea through Sudan,

You are fighting a predatory flock of sands,

And when you approach the ocean,

You can't see the shores in your middle.You're wearing beads on a jasper plate,

Painted patterned boats are dancing,

And in the boats there are majestic black people

Your good deeds are praised...

The Russian poet admires the land that gave his homeland the ancestor of the great A.S. Pushkin. (Verse “Abyssinia”).

August 3, 1921 N. Gumilev was arrested on suspicion of participation in a conspiracy against Soviet power. This was the so-called “Tagantsev case.”

August 24, 1921 Petrograd. Gubcheka adopted a resolution to shoot the participants in the “Tagantsev conspiracy” (61 people), including N. Gumilyov.

His participation in the conspiracy has not been established. Gumilyov did not publish a single counter-revolutionary line. I was not involved in politics. Gumilyov became a victim of cultural terror.

The poet lived for 35 years. Now his second life has begun - his return to the reader.

P: Let's sum it up results.

Gumilyov's personality is unusually bright. He is a talented poet, a brave traveler and a brave warrior. His childhood passed in a calm, unremarkable environment, but self-education strengthened Gumilyov’s character.

Homework:

1. Write an essay on the topic: “The most remarkable pages from the life of N. Gumilev.” (Tell about your favorite stage of N.S. Gumilyov’s life, justify your choice.

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov lived a very bright, but short, forcibly interrupted life. Indiscriminately accused of an anti-Soviet conspiracy, he was shot. He died on a creative rise, full of bright ideas, a universally recognized Poet, theorist of verse, and an active figure in the literary front.

And for over six decades his works were not republished; a severe ban was imposed on everything he created. The very name of Gumilyov was passed over in silence. It was only in 1987 that it became possible to speak openly about his innocence.

Gumilyov's entire life, right up to his tragic death, is unusual, fascinating, and testifies to the rare courage and fortitude of an amazing personality. Moreover, her formation took place in a calm, unremarkable environment. Gumilev found his own tests.

The future poet was born into the family of a ship's doctor in Kronstadt. He studied at the Tsarskoye Selo gymnasium. In 1900-1903 lived in Georgia, where my father was assigned. Upon his family’s return, he continued his studies at the Nikolaev Tsarskoye Selo Gymnasium, which he graduated from in 1906. However, already at this time he devoted himself to his passion for poetry.

He published his first poem in the Tiflis leaflet (1902), and in 1905 he published a whole book of poems, “The Path of the Conquistadors.” Since then, as he himself later noted, he has been completely taken over by “the pleasure of creativity, so divinely complex and joyfully difficult.”

Creative imagination awakened in Gumilyov a thirst for knowledge of the world. He goes to Paris to study French literature. But he leaves the Sorbonne and goes, despite his father’s strict prohibition, to Africa. The dream of seeing mysterious lands changes all previous plans. The first trip (1907) was followed by three more in the period from 1908 to 1913, the last as part of an ethnographic expedition organized by Gumilev himself.

In Africa, he experienced many hardships and illnesses; he undertook dangerous trials that threatened death of his own free will. As a result, he brought valuable materials from Abyssinia for the St. Petersburg Museum of Ethnography.

It is usually believed that Gumilyov strove only for the exotic. The wanderlust was most likely secondary. He explained it to V. Bryusov this way: “... I’m thinking of going to Abyssinia for six months in order to find new words in a new environment.” Gumilyov constantly thought about the maturity of poetic vision.

During the First World War he volunteered for the front. In correspondence from the scene of hostilities, he reflected their tragic essence. He did not consider it necessary to protect himself and participated in the most important maneuvers. In May 1917 he left of his own free will for the Entente operation in Thessaloniki (Greece).

Gumilev returned to his homeland only in April 1918. And he immediately became involved in intense activity to create a new culture: he lectured at the Institute of Art History, worked on the editorial board of the publishing house “World Literature”, in a seminar of proletarian poets, and in many other areas of culture.

An eventful life did not prevent the rapid development and flourishing of a rare talent. Gumilyov's poetry collections were published one after another: 1905 - “The Path of the Conquistadors”, 1908 - “Romantic Flowers”, 1910 - “Pearls”, 1912 - “Alien Sky”, 1916 - “Quiver”, 1918 - “ Bonfire", "Porcelain Pavilion" and the poem "Mick", 1921 - "Tent" and "Pillar of Fire".

Gumilyov also wrote prose and drama, kept a unique chronicle of poetry, studied the theory of verse, and responded to the phenomena of art in other countries. How he managed to fit all this into just a decade and a half remains a secret. But he managed and immediately attracted the attention of famous literary figures.

The thirst for discovering unknown beauty was still not satisfied. The bright, mature poems collected in the book “Pearls” are devoted to this cherished topic. From the glorification of romantic ideals, the poet came to the theme of quests, his own and universal. “A sense of the path” (Blok’s definition; here the artists overlapped, although they were looking for different things) permeated the collection of “Pearls”. Its very name comes from the image beautiful countries: “Where no human has gone before,/Where giants live in sunny groves/And pearls shine in the clear water.” The discovery of values justifies and spiritualizes life. Pearls became a symbol of these values. And the symbol of search is travel. This is how Gumilyov reacted to the spiritual atmosphere of his time, when the definition of a new position was the main thing.

As before, the poet’s lyrical hero is inexhaustibly courageous. On the way: a bare cliff with a dragon - its “sigh” - a fiery tornado.” But the conqueror of peaks knows no retreat: “Better is the blind Nothing, / Than the golden Yesterday...” That is why the flight of the proud eagle is so compelling. The author's imagination seems to complete the perspective of his movement - “not knowing decay, he flew forward”:

He died, yes! But he couldn't fall

Having entered the circles of planetary movement,

The bottomless maw gaped below,

But the gravitational forces were weak.

The small cycle “Captains,” about which so many unfair judgments have been made, was born of the same striving forward, the same admiration for the feat:

“No one trembles before a thunderstorm,

Not one will furl the sails."

Gumilyov cherishes the deeds of unforgettable travelers: Gonzalvo and Cuca, La Perouse and de Gama... With their names included in the “Captains” is the poetry of great discoveries, the unbending fortitude of all, “who dares, who wants, who seeks” (isn’t this where you need to see the reason for the severity, previously interpreted sociologically: “Or, having discovered a riot on board, / A pistol is torn from his belt”?).

In "Pearls" there are exact realities, say, in the picture of the coastal life of sailors ("Captains"). However, distracting from the boring present, the poet seeks harmonies with the rich world of accomplishments and freely moves his gaze in space and time. Images appear different centuries and countries, in particular included in the titles of the poems: “The Old Conquistador”, “Barbarians”, “Knight with a Chain”, “Journey to China”. It is the movement forward that gives the author confidence in the chosen idea of the path. And also a form of expression.

Tragic motives are also palpable in “Pearls” - unknown enemies, “monstrous grief”. Such is the power of the inglorious surroundings. His poisons penetrate the consciousness of the lyrical hero. The “always patterned garden of the soul” turns into a hanging garden, where it is so scary, so low, the face of the moon bends - not the sun.

The trials of love are filled with deep bitterness. Now it is not betrayal that frightens, as in the early poems, but the loss of the “ability to fly”: signs of “dead, languid boredom”; “kisses are stained with blood”; the desire to “bewitch the gardens to the painful distance”; in death to find “islands of perfect happiness.”

The truly Gumilevian spirit is boldly demonstrated - the search for the land of happiness even beyond the boundaries of existence. The darker the impressions, the more persistent the attraction to the light. The lyrical hero strives for extremely strong tests: “I will once again burn with the rapturous life of fire.” Creativity is also a type of self-immolation: “Here, own a magic violin, look into the eyes of monsters/And die a glorious death, the terrible death of a violinist.”

In the article “The Life of a Poem,” Gumilyov wrote: “By gesture in a poem, I mean such an arrangement of words, a selection of vowels and consonants, accelerations and decelerations of rhythm, that the reader of the poem involuntarily takes the pose of a hero, experiences the same thing as the poet himself... “Gumilyov had such mastery.

A tireless search determined Gumilyov’s active position in the literary community. He soon became a prominent employee of the Apollo magazine, organized the “Workshop of Poets,” and in 1913, together with S. Gorodetsky, formed a group of Acmeists.

The most acmeistic collection, “Alien Sky” (1912), was also a logical continuation of the previous ones, but a continuation of a different aspiration, different plans.

In the “alien sky” the restless spirit of search is again felt. The collection included short poems “The Prodigal Son” and “The Discovery of America.” It would seem that they were written on a truly Gumilevian theme, but how it has changed!

Next to Columbus in “The Discovery of America” stood an equally significant heroine - the Muse of Distant Journeys. The author is now captivated not by the greatness of the act, but by its meaning and the soul of the chosen one of fate. Perhaps for the first time, there is no harmony in the inner appearance of the traveling heroes. Let's compare internal state Columbus before and after his journey: He sees a miracle with his spiritual eye.

A whole world unknown to the prophets,

What lies in the blue abysses,

Where the west meets the east.

And then Columbus about himself: I am a shell, but without pearls,

I am a stream that has been dammed.

Deflated, now no longer needed.

"Like a lover, for the game is different

He is abandoned by the Muse of Far Traveling."

The analogy with the artist’s aspirations is unconditional and sad. There is no “pearl”, the naughty muse has abandoned the daring one. The poet thinks about the purpose of the search.

The time for youthful illusions is over. And the turn of the late 1900s - early 1910s. was a difficult and turning point for many. Gumilyov also felt this. Back in the spring of 1909, he said in connection with a book of critical articles by I. Annensky: “The world has become larger than man. An adult (are there many of them?) is happy to fight. He is flexible, he is strong, he believes in his right to find a land where he can live.” I also strived for creativity. In “Alien Sky” there is a clear attempt to establish the true values of existence, the desired harmony.

Gumilyov is attracted by the phenomenon of life. She is presented in an unusual and capacious image - “with an ironic grin, a child king on the skin of a lion, forgetting toys between his white tired hands.” Life is mysterious, complex, contradictory and alluring. But its essence escapes. Having rejected the unsteady light of unknown “pearls”, the poet nevertheless finds himself in the grip of previous ideas - about the saving movement to distant limits: We are walking through the foggy years,

Vaguely feeling the scent of roses,

In centuries, in spaces, in nature

Conquer ancient Rhodes.

But what about the meaning of human existence? Gumilev finds the answer to this question for himself from Théophile Gautier. In an article dedicated to him, the Russian poet highlights principles close to both of them: to avoid “both the accidental, concrete, and the vague, abstract”; to know the “majestic ideal of life in art and for art.” The unsolvable turns out to be the prerogative of artistic practice. In “Alien Sky” Gumilev includes a selection of Gautier’s poems in his translation. Among them are inspired lines about the imperishable beauty created by man. Here's an idea for the ages:

All ashes.--One, rejoicing,

Art will not die.

The people will survive.

This is how the ideas of “Acmeism” matured. And the “immortal features” of what was seen and experienced were cast in poetry. Including in Africa. The collection includes “Abyssinian Songs”: “Military”, “Five Bulls”, “Slave”, “Zanzibar Girls”, etc. In them, unlike other poems, there are many rich realities: everyday, social. The exception is understandable. “Songs” creatively interpreted the folklore works of the Abyssinians. In general, the path from life observation to the image of Gumilyov is very difficult.

The artist's attention to his surroundings has always been keen.

He once said: “A poet should have a Plyushkin farm. And the rope will come in handy. Nothing should go to waste. Everything for poetry." The ability to preserve even a “string” is clearly felt in the “African Diary”, stories, a direct response to the events of the First World War - “Notes of a Cavalryman”. But, according to Gumilyov, “poetry is one thing, but life is another.” In "Art" (from Gautier's translations) there is a similar statement:

“The creation is all the more beautiful,

What material was taken from?

More dispassionate."

This is how he was in Gumilyov’s lyrics. Specific signs disappeared, the gaze embraced the general, significant. But the author’s feelings, born of living impressions, acquired flexibility and strength, gave rise to bold associations, attraction to other calls of the world, and the image acquired visible “thingness”.

The collection of poems “Quiver” (1916) was not forgiven for many years, accusing him of chauvinism. Gumilyov, as well as other writers of that time, had motives for the victorious struggle against Germany and asceticism on the battlefield. Patriotic sentiments were close to many. A number of facts from the poet’s biography were also perceived negatively: voluntary joining the army, heroism shown at the front, the desire to participate in the actions of the Entente against the Austro-German-Bulgarian troops in the Greek port of Thessaloniki, etc. The main thing that caused sharp rejection was a line from “Pentameter iambics": "In the silent call of the battle trumpet/I suddenly heard the song of my fate..." Gumilyov regarded his participation in the war as his highest destiny, fought, according to eyewitnesses, with enviable calm courage, and was awarded two crosses. But such behavior testified not only to an ideological position, but also to a moral and patriotic one. Regarding the desire to change place military activities, then here again the power of the Muse of Distant Wanderings was felt.

In “Notes of a Cavalryman,” Gumilev revealed all the hardships of war, the horror of death, and the torment of the rear. Nevertheless, this knowledge was not the basis for the collection. Seeing the people's troubles, Gumilyov came to a broad conclusion: “The spirit<...>as real as our body, only infinitely stronger.”

The lyrical hero is attracted to “Quiver” by similar inner insights. B. Eikhenbaum keenly saw in it the “mystery of the spirit,” although he attributed it only to the military era. The philosophical and aesthetic sound of the poems was, of course, richer.

Back in 1912, Gumilyov soulfully said about Blok: the two sphinxes “make him “sing and cry” with their insoluble riddles: Russia and his own soul.” “Mysterious Rus'” in “Quiver” also raises sore points. But the poet, considering himself “not a tragic hero” - “more ironic and drier,” comprehends only his attitude towards her:

Oh, Rus', harsh sorceress,

You will take yours everywhere.

Run? But do you like new things?

Or can you live without you?

Is there a connection between Gumilyov’s spiritual quest, captured in “Quiver,” and his subsequent behavior in life?

Apparently there is, although it is complex and elusive. The thirst for new, unusual impressions draws Gumilyov to Thessaloniki, where he leaves in May 1917. He also dreams of a longer journey - to Africa. It seems impossible to explain all this only by the desire for exoticism. It is no coincidence that Gumilyov travels in a roundabout way - through Finland, Sweden, and many countries. Another thing is indicative. After not getting to Thessaloniki, he lives comfortably in Paris, then in London, he returns to the revolutionary cold and hungry Petrograd of 1918. The homeland of a harsh, turning point era was perceived, probably, as the deepest source of self-knowledge creative personality. No wonder Gumilyov said: “Everyone, all of us, despite decadence, symbolism, Acmeism and so on, are, first of all, Russian poets.” The best collection of poems, “Pillar of Fire” (1921), was written in Russia.

Gumilyov did not come to the lyrics of “Pillar of Fire” right away. A significant milestone after “The Quiver” were the works of his Paris and London albums, published in “The Fire” (1918). Already here the author’s thoughts about his own worldview prevail. He proceeds from the “smallest” observations - of the trees, the “orange-red sky”, the “honey smelling meadow”, the “sick” in the ice-drifted river. The rare expressiveness of the “landscape” is amazing. But it is not nature itself that captivates the poet. Instantly, before our eyes, the secret of the bright sketch is revealed. This clarifies the true purpose of the verses. Is it possible, for example, to doubt a person’s courage after hearing his call to the “scarce” earth: “And become, as you are, a star / permeated through and through with Fire!”? He looks everywhere for opportunities to “rush after the light.” It’s as if Gumilyov’s former dreamy, romantic hero has returned to the pages of the new book. No, this is the impression of a moment. Mature, sad comprehension of existence and one’s place in it is the epicenter of “Bonfire.” Now, perhaps, it is possible to explain why the long road called to the poet. The poem “Eternal Memory” contains an antinomy: And here is all life!

Whirling, singing,

Seas, deserts, cities,

Flickering reflection

Lost forever.

And here again delight and grief,

Again, as before, as always,

The sea waves its gray mane,

Deserts and cities rise.

The hero wants to return what is “lost forever” to humanity, not to miss something real and unknown in the inner being of people. Therefore, he calls himself a “gloomy wanderer” who “must travel again, must see.” Under this sign, encounters with Switzerland, the Norwegian mountains, the North Sea, and a garden in Cairo appear. And on a material basis, capacious, generalizing images of sad wandering are formed: wandering - “like along the beds of dried up rivers,” “blind transitions of space and time.” Even in a loop love lyrics(D. Gumilyov experienced an unhappy love for Elena in Paris) the same motives are read. The beloved leads “the heart to heights,” “scattering stars and flowers.” Nowhere, as here, did such sweet delight in front of a woman sound. But happiness is only in a dream, in delirium. But in reality - longing for the unattainable:

Here I stand before your door,

There is no other way given to me.

Even though I know that I wouldn't dare

Never enter this door.

The already familiar spiritual collisions in the works of “The Pillar of Fire” are embodied immeasurably deeper, more multifaceted and more fearlessly. Each of them is a pearl. It is quite possible to say that with his word the poet created this long-sought treasure. This judgment does not contradict the general concept of the collection, where creativity is given the role of a sacred act. There is no gap between what is desired and what is accomplished for an artist.

The poems are born of eternal problems - the meaning of life and happiness, the contradiction of soul and body, ideal and reality. Addressing them imparts to poetry a majestic severity, precision of sound, the wisdom of the parable, and aphoristic precision. One more feature is organically woven into the seemingly rich combination of these features. It comes from a warm, excited human voice. More often - the author himself in an uninhibited lyrical monologue. Sometimes - objectified, although very unusual, “heroes”. Emotional coloring complex philosophical search makes it, the search, part of the living world, causing excited empathy.

Reading The Pillar of Fire awakens a feeling of ascent to many heights. It is impossible to say which dynamic turns of the author’s thought are more disturbing in “Memory”, “Forest”, “Soul and Body”. Already the opening stanza of “Memory” strikes our thoughts with a bitter generalization: Only snakes shed their skins.

So that the soul ages and grows,

Unfortunately, we are not like snakes,

We change souls, not bodies.

Then the reader is shocked by the poet's confession about his past. But at the same time, a painful thought about the imperfection of human destinies. These first nine heartfelt quatrains suddenly lead to a chord that transforms the theme: I am a gloomy and stubborn architect

Temple rising in the darkness

I was jealous of the glory of the Father

As in heaven and on earth.

And from him - to the dream of the flourishing of the earth, our native country. And here, however, there is no end yet. The final lines, partially repeating the original ones, carry a new sad meaning - a feeling of the temporary limitations of human life. The poem, like many others in the collection, has a symphonic development.

Gumilyov achieves rare expressiveness by combining incompatible elements. Forest in the same name lyrical work uniquely quirky. Giants, dwarfs, lions live in it, and a “woman with a cat’s head” appears. This is “a country that you can’t even dream about.” However, the cat-headed creature is given communion by an ordinary curate. Fishermen and... peers of France are mentioned next to the giants. What is this - a return to the phantasmagoria of early Gumilevian romance? No, the fantastic was captured by the author: “Maybe that forest is my soul...” To embody complex, intricate inner impulses, such bold associations were made. In “The Baby Elephant” the title image is connected with something difficult to connect—the experience of love. She appears in two forms: imprisoned “in a tight cage” and strong, like that elephant “that once carried Hannibal to the trembling Rome.” “The Lost Tram” symbolizes a crazy, fatal movement into “nowhere.” And it is furnished with terrifying details of the dead kingdom. Moreover, sensory-changeable mental states are closely linked with it. This is how the tragedy of human existence in general and of a specific individual is conveyed. Gumilev used the right of an artist with enviable freedom, and most importantly, achieving a magnetic force of influence.

The poet seemed to constantly push the narrow boundaries of the poem. Unexpected endings played a special role. The triptych “Soul and Body” seems to continue the familiar theme of “Quiver” - only with new creative energy. And in the end - the unexpected: all human impulses, including spiritual ones, turn out to be a “faint reflection” of a higher consciousness. “The Sixth Sense” immediately captivates you with the contrast between the meager pleasures of people and genuine beauty and poetry. It seems that the effect has been achieved. Suddenly, in the last stanza, the thought breaks out to other boundaries:

So, century after century - how soon, Lord? --

Under the scalpel of nature and art,

Our spirit screams, our flesh faints,

Giving birth to an organ for the sixth sense.

Line-by-line images, with a wonderful combination of the simplest words and concepts, also lead our thoughts to distant horizons. It is impossible to react differently to such finds as “a scalpel of nature and art”, “a ticket to India of the Spirit”, “a garden of dazzling planets”, “Persian diseased turquoise”...

The secrets of poetic witchcraft in “The Pillar of Fire” are countless. But they arise on the same path, difficult in its own way. main goal- to penetrate into the origins of human nature, the desired prospects of life, into the essence of being. Gumilyov’s worldview was far from optimistic. Personal loneliness took its toll, which he could never avoid or overcome. No public position was found. The turning points of the revolutionary times aggravated past disappointments in individual fate and the whole world. The author of “The Pillar of Fire” captured the painful experiences in the ingenious and simple image of a “lost tram”:

He rushed like a dark, winged storm,

He got lost in the abyss of time...

Stop, driver,

Stop the carriage now.

“The Pillar of Fire,” nevertheless, concealed in its depths an admiration for bright, beautiful feelings, the free flight of beauty, love, and poetry. Gloomy forces are everywhere perceived as an unacceptable obstacle to spiritual uplift:

Where all the sparkle, all the movement,

Everyone sings - you and I live there;

Everything here is just our reflection

Filled with a rotting pond.

The poet expressed an unattainable dream, a thirst for happiness not yet born by man. Ideas about the limits of existence are boldly expanded.

Gumilyov taught and, I think, taught his readers to remember and love “All the cruel, sweet life,

All my native, strange land...”

He saw both life and the earth as endless, beckoning with their distances. Apparently, this is why he returned to his African impressions (“Tent”, 1921). And, without getting to China, he made an adaptation of Chinese poets (“Porcelain Pavilion”, 1918).

In “The Bonfire” and “The Pillar of Fire” one found “touches on the world of the mysterious”, “a rush into the world of the unknowable”. This probably meant Gumilyov’s attraction to “his inexpressible nickname” hidden in the recesses of his soul. But this is most likely how the opposition to the limited human powers, a symbol of unprecedented ideals. They are akin to the images of divine stars, sky, planets. With some “cosmic” associations, the poems in the collections expressed aspirations of a completely earthly nature. And yet, it is hardly possible to speak, as is allowed now, even of Gumilyov’s late work as “realistic poetry.” He retained here too the romantic exclusivity, the whimsicality of spiritual metamorphoses. But it is precisely this way that the poet’s word is infinitely dear to us.

Nikolai GUMILEV (1886-1921)

- Gumilyov's childhood and youth.

- Gumilyov's early work.

- Travels in the works of Gumilyov.

- Gumilyov and Akhmatova.

- Gumilyov's love lyrics.

- Philosophical lyrics of Gumilyov.

- Gumilev and the First World War.

- War in the works of Gumilyov.

- The theme of Russia in the works of Gumilyov.

- Dramaturgy of Gumilyov.

- Gumilev and the revolution.

- Biblical motifs in Gumilyov's lyrics.

- Arrest and execution of Gumilyov.

The legacy of N. S. Gumilev, a poet of rare individuality, only recently, after many years of oblivion, came to the reader. His poetry attracts with its novelty and acuteness of feelings, excited thought, graphic clarity and rigor of the poetic design.

- Gumilyov's childhood and youth.

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov was born on April 3 (15), 1886 in Kronstadt in the family of a naval doctor. Soon his father retired, and the family moved to Tsarskoye Selo. Here, in 1903, Gumilyov entered the 7th grade of the gymnasium, the director of which was the wonderful poet and teacher I. F. Annensky, who had a huge influence on his student. Gumilyov wrote about the role of I. Annensky in his fate in his 1906 poem “In Memory of Annensky”:

To such unexpected and melodious nonsense,

Calling people's minds with me,

Innokenty Annensky was the last

From Tsarskoye Selo swans.

After graduating from high school, Gumilyov went to Paris, where he attended lectures on French literature at the Sorbonne University and studied painting. Returning to Russia in May 1908, Gumilyov devoted himself entirely to creative work, establishing himself as an outstanding poet and critic, a theorist of verse, and the author of the now widely known book of art criticism, “Letters on Russian Poetry.”

2. Gumilyov’s early work.

Gumilyov began writing poetry when he was still in high school. In 1905, the 19-year-old poet published his first collection, “The Path of the Conquistadors.” Soon, in 1908, the second, “Romantic Flowers,” followed, and then the third, “Pearls” (1910), which brought him wide fame.

At the beginning creative path N. Gumilyov joined the Young Symbolists. However, he became disillusioned with this movement quite early and became the founder of Acmeism. At the same time, he continued to treat the Symbolists with due respect, as worthy teachers and predecessors, virtuosos of the artistic form. In 1913, in one of his program articles “The Legacy of Symbolism and Acmeism,” Gumilev, stating that “symbolism has completed its circle of development and is now falling,” added: “Symbolism was a worthy father.”

Gumilyov's early poems are dominated by an apology for the strong-willed principle, romanticized ideas about a strong personality who decisively asserts himself in the fight against enemies (“Pompeii among the pirates”), in tropical countries, in Africa and South America.

The heroes of these works are powerful, cruel, but also courageous, although soulless conquerors, conquistadors, discoverers of new lands, each of them in a moment of danger, hesitation and doubt

Or, having discovered a riot on Borg,

A pistol bursts from his belt,

So that gold falls from the lace,

From pinkish Brabant cuffs.

The quoted lines are taken from the ballad “Captains”, included in the collection “Pearls”. They very clearly characterize Gumilyov’s poetic sympathies for people of this type,

Whose is not the dust of lost charters -

The chest is soaked with the salt of the sea,

Who is the needle on the torn map

Marks his daring path.

The fresh wind of real art fills the “sails” of such poems, which are certainly related to romantic tradition Kipling and Stevenson.

3. Travels in the works of Gumilyov.

Gumilyov traveled a lot. A voluntary wanderer and pilgrim, he traveled and walked thousands of miles, visited the impenetrable jungles of Central Africa, languished with thirst in the sands of the Sahara, got stuck in the swamps of Northern Abyssinia, touched the ruins of Mesopotamia with his hands... And it is no coincidence that exoticism became not only the theme of Gumilyov’s poems: it the very style of his works is imbued. He called his poetry the Muse of Far Travels, and remained faithful to it until the end of his days. With everything there is a lotThe image of the themes and philosophical depth of the late Gumilyov, poems about his travels and wanderings cast a very special light on his entire work.

The leading place in Gumilyov's early poetry is occupied by African theme. Poems about Africa, so distant and mysterious in the minds of readers at the beginning of the century, gave a special originality to Gumilyov’s work. The poet's African poems are a tribute to his deep love for this continent and its people. Africa in his poetry is covered in romance and full of attractive power: “The heart of Africa is full of singing and flaming” (“Niger”). This is a magical country, full of charm and surprises (“Abyssinia”, “Red Sea”, “African Night”, etc.).

Deafened by the roar and stomping,

Cloaked in flames and smoke,

About you, my Africa, in a whisper

The seraphim speak in the skies.

One can only admire the love of the Russian poet-traveler for this continent. He visited Africa as a true friend and ethnographer. It is no coincidence that in distant Ethiopia they still keep a good memory of N. Gumilyov.

Glorifying the discoverers and conquerors of distant lands, the poet did not shy away from depicting the destinies of the peoples they conquered. Such, for example, is the poem “Slave” (1911), in which slave slaves dream of piercing the body of their European oppressor with a knife. In the poem “Egypt”, the author’s sympathy is evoked not by the rulers of the country - the British, but by its true masters, those

Who leads the Black buffaloes into the field with a plow or harrow?

Gumilyov's works about Africa are characterized by vivid imagery and poetry. Often even simple geographical name(“Sudan”, “Zambezi”, “Abyssinia”, “Niger”, etc.) entail in them a whole chain of various pictures and associations. Full of secrets and exoticism, sultry air and unknown plants, amazing birds and animals, the African world in Gumilyov’s poems captivates with its generosity of sounds and colors, multicolor palette:

All day above the water, like a flock of dragonflies,

Golden flying fish are visible,

At the sandy, sickle-curved spits,

The shallows are like flowers, green and red.

("Red sea").

Gumilyov’s first poem “Mick”, a colorful story about a little Abyssinian captive named Mick, his friendship with an old baboon and a white boy Louis, and their joint escape to the city of monkeys, was evidence of the poet’s deep and devoted love for the distant African continent.

As the leader of Acmeism, Gumilev demanded great formal skill from poets. In his treatise “The Life of Verse,” he argued that in order to live through the ages, a poem, in addition to thought and feeling, must have “the softness of the outlines of a young body ... and the clarity of a statue illuminated by the sun; simplicity - for her alone the future is open, and - sophistication, as a living recognition of continuity from all the joys and sorrows of past centuries...” His own poetry is characterized by precise verse, harmonious composition, and emphasized rigor in the selection and combination of words.

In the poem “To the Poet” (1908), Gumilyov expressed his creative credo this way:

Let your verse be flexible and resilient,

Like the poplar of a green valley,

Like the chest of the earth where the plow has plunged,

Like a girl who has never known a man.

Take care of confident rigor,

Your verse should neither flutter nor beat.

Although the muse has light steps

She is a goddess, not a dancer.

There is clearly a echo here with Pushkin, who also considered art to be the highest sphere of spiritual existence, a shrine, a temple, which should be entered with deep reverence:

The service of the muses does not tolerate vanity, the Beautiful must be majestic.

Already the poet’s first poems are replete with vivid comparisons, original epithets and metaphors, emphasizing the diversity of the world, its beauty and variability:

And the sun is lush in the distance

Dreamed of dreams of abundance,

And kissed the face of the earth

In the languor of sweet impotence.

And in the evenings in the sky

Scarlet clothes were burning,

And stained, in tears,

The Doves of Hope Wept

("Autumn Song")

Gumilev is primarily an epic poet, his favorite genre is the ballad with its energetic rhythm. At the same time, the exotic, pathetically elevated poetry of early Gumilyov is sometimes somewhat cold.

4. Gumilyov and Akhmatova.

Changes in his work occur in the 1910s. And they are largely connected with personal circumstances: with meeting and then marrying A. Akhmatova (then Anna Gorenko). Gumilyov met her back in 1903, at the skating rink, fell in love, proposed several times, but received consent to marriage only in the spring of 1910. Gumilev will write about it like this: From the lair of the serpent, From the city of Kyiv, I took not a wife, but a sorceress. And I thought - a funny one, I guessed - a wayward one, A cheerful songbird.

If you call, he winces, If you hug him, he puffs up, And the moon comes out, and he becomes languid, And he looks and groans, As if he’s burying Someone, and he wants to drown himself. (“From the Lair of the Serpent”)

After the release of the collection “Pearls,” Gumilev firmly secured the title of a recognized master of poetry. As before, his many works reek of exoticism, unusual and unfamiliar images of Africa, dear to his heart. But now the dreams and feelings of the lyrical hero become more tangible and earthly. (In the 1910s, love lyrics and poetry of emotional movements began to appear in the poet’s work; there was a desire to penetrate into the inner world of his characters, previously battened down by a hard shell of inaccessibility and power, and especially into the soul of the lyrical hero. This did not always work out successfully, for Gumilyov resorted to some poems on this topic have a false romantic surroundings, such as:

I approached, and then instantly,

Like an animal, fear grabbed hold of me:

I met a hyena's head

On slender girlish shoulders.

But in Gumilyov’s poetry there are many poems that can rightfully be called masterpieces, the theme of love sounds so deeply and piercingly in them. Such, for example, is the poem “About You” (1916), permeated with deep feeling, it sounds like the apotheosis of a beloved:

About you, about you, about you,

Nothing, nothing about me!

In human dark fate

You are a winged call to the heights.

Your noble heart -

Like a coat of arms of bygone times.

Existence is illuminated by it

All earthly, all wingless tribes.

If the stars are clear and proud,

They will turn away from our land,

She has two top stars:

These are your brave eyes.

Or here is the poem “To a Girl” (1911), dedicated to the 20th anniversary of Masha Kuzmina-Karavaeva, the poet’s cousin on her mother’s side:

I don't like languor

of your crossed arms,

And calm modesty,

And bashful fear.

The heroine of Turgenev's novels,

You are arrogant, gentle and pure,

There is so much of stormless autumn in you

From the alley where the sheets are circling.

Many of Gumilyov’s poems reflected his deep feeling for Anna Akhmatova: “Ballad”, “Poisoned”, “Beast Tamer”, “By the Fireplace”, “One Evening”, “She”, etc. Such, for example, is beautifully created by the master poet the image of a wife and poet from the poem “She”:

I know a woman: silence,

Fatigue is bitter from words

Lives in a mysterious flicker

Her dilated pupils.

Her soul is open greedily

Only the copper music of verse,

Before a distant and joyful life

Arrogant and deaf.

She is bright in the hours of languor

And holds lightning in his hand,

And her dreams are as clear as shadows

On the heavenly fiery sand.

5. Love lyrics by Gumilyov.

TO the best works Gumilev’s love lyrics should also include the poems “When I was in love”, “You couldn’t or didn’t want to”, “You regretted it, you forgave”, “Everything is pure for a pure look” and others. Gumilyov's love appears in a variety of manifestations: sometimes as a “tender friend” and at the same time a “merciless enemy” (“Scattering Stars”), sometimes like a “winged call to heights” (“About You”). “Only love remains for me...”, the poet confesses in the poems “Canzone One” and “Canzone Two”, where he comes to the conclusion that the most gratifying thing in the world is “the trembling of our dear eyelashes//And the smile of our beloved lips.”

Gumilyov's lyrics present a rich gallery of female characters and types: fallen, chaste, royally inaccessible and inviting, humble and proud. Among them: a passionate eastern queen (“Barbarians”), a mysterious sorceress (“The Witch”), the beautiful Beatrice, who left paradise for her beloved (“Beatrice”) and others.

The poet lovingly draws a noble appearancea woman who knows how to forgive insults and generously give joy, understand the storms and doubts crowding in the soul of her chosen one, filled with deep gratitude “for the dazzling happiness // To be with you at least sometimes.” The poeticization of women also revealed the knightly nature of Gumilyov’s personality.

6. Philosophical lyrics of Gumilyov.

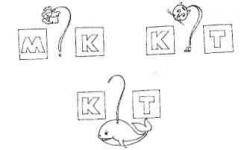

In the best poems of the collection “Pearls,” the pattern of Gumilev’s verse is clear and deliberately simple. The poet creates visible pictures:

I look at the melting block,

To the reflection of pink lightning,

And my smart cat catches fish

And lures birds into the net.

The poetic picture of the world in Gumilyov’s poems attracts with its specificity and tangibility of images. The poet even materializes music. He sees, for example, how

The sounds rushed and shouted Like a vision, like giants, And rushed about in the echoing hall, And dropped diamonds.

The “diamonds” of words and sounds of Gumilev’s best poems are exceptionally colorful and dynamic. His poetic world extremely picturesque, full of expression and love of life. Clear and elastic rhythm, bright, sometimes excessive imagery are combined in his poetry with classical harmony, precision, and thoughtfulness of form, which adequately embodies the richness of the content.

In his poetic depiction of life and man, N. Gumilyov was able to rise to the depths philosophical thoughts and generalizations, revealing an almost Pushkin or Tyutchev force. He thought a lot about the world, about God, about the purpose of man. And these thoughts were reflected in various ways in his work. The poet was convinced that in everything and always “the Lord’s word nourishes us better than bread.” It is no coincidence that a significant part of it poetic heritage compose poems and poems inspired by gospel stories and images, imbued with love for Jesus Christ.

Christ was Gumilyov's moral and ethical ideal, and the New Testament was a reference book. Gospel stories, parables, instructions are inspired by Gumilyov’s poem “The Prodigal Son”, the poems “Christ”, “Gates of Paradise”, “Paradise”, “Christmas in Abyssinia”, “Your Temple. Lord, in heaven..." and others. Reading these works, one cannot help but notice what an intense struggle takes place in the soul of his lyrical hero, how he rushes between opposing feelings: pride and humility.

The foundations of the Orthodox faith were laid in the minds of the future poet as a child. He was raised in a religious family. His mother was a true believer. Anna Gumileva, the wife of the poet’s older brother, recalls: “The children were raised in the strict rules of the Orthodox religion. Mother often came with them to the chapel to light a candle, which Kolya liked. Kolya loved to go to church, light a candle, and sometimes prayed for a long time in front of the icon of the Savior. From childhood he was religious and remained the same until the end of his days - a deeply religious Christian.”

His student Irina Odoevtseva, who knew the poet well, writes in her book “On the Banks of the Neva” about Gumilyov’s visits to church services and his convinced religiosity. Nikolai Gumilyov’s religiosity helps us understand a lot about his character and creativity.

Gumilyov’s thoughts about God are inseparable from thoughts about man, his place in the world. The poet’s worldview concept received extremely clear expression in the final stanza of the poetic short story “Fra Beato Angelico”:

There is God, there is peace, they live forever,

And people's lives are instantaneous and miserable.

But a person contains everything within himself.

Who loves the world and believes in God.

All the poet’s work is the glorification of man, the capabilities of his spirit and willpower. Gumilyov was passionately in love with life, with its diverse manifestations. And he sought to convey this love to the reader, to make him a “knight of happiness,” because happiness, he is convinced, depends, first of all, on the person himself.

In the poem “Knight of Fortune” he writes:

How easy it is to breathe in this world!

Tell me who is dissatisfied with life.

Tell me who takes a deep breath

I am free to make everyone happy.

Let him come, I'll tell him

About a girl with green eyes.

About the blue morning darkness.

Pierced by rays and poetry.

Let him come. I have to tell

I have to tell it again and again.

How sweet it is to live, how sweet it is to win

The sea and girls, enemies and the word.

And if he still doesn’t understand.

My beautiful one will not accept faith

And he will complain in turn

To the world's sorrow, to the pain - to the barrier!

It was a symbol of faith. He categorically did not accept pessimism, despondency, dissatisfaction with life, “world sorrow”.It was not for nothing that Gumilyov was called a poet-warrior. Traveling and testing himself with danger were his passion. He wrote prophetically about himself:

I I won't die in bed

With a notary and a doctor,

And in some wild crevice.

Drowned in thick ivy ( "Me and you).

7. Gumilyov and the First World War.

When did the first one start? World War, Gumilyov volunteered to go to the front. His bravery and contempt for death became legendary. Two soldier's Georges are the highest awards for a warrior and serve as the best confirmation of his courage. Gumilyov spoke about episodes of his military life in “Notes of a Cavalryman” in 1915 and in a number of poems in the collection “Quiver”. As if summing up his military fate, he wrote in the poem “Memory”:

He knew the pangs of cold and thirst.

An anxious dream, an endless journey.

But Saint George touched twice

I shoot the untouched breast.

We cannot agree with those who consider Gumilyov’s war poems to be chauvinistic, glorifying the “sacred cause of war.” The poet saw and realized the tragedy of the war. In one of his poems’he wrote;

And the second year is drawing to a close. But banners also fly. And war also violently mocks our wisdom.

8. War in the works of Gumilyov.

Gumilyov was attracted by the vivid romanticization of the feat, for he was a man of a knightly soul. War in his depiction appears as a phenomenon akin to a rebellious, destructive, disastrous verse. That is why we so often see in his poems the likening of battle to a thunderstorm. The lyrical hero of these works plunges into the fiery element of battle without fear or despondency, although he understands that death awaits him at every step:

She is everywhere - and in the glow of a fire,

And in the dark, unexpected and close.

Then on the horse of a Hungarian hussar,

And then with the gun of a Tyrolean shooter.

Courageous overcoming of physical difficulties and suffering, fear of death, the triumph of the spirit over the body became one of the main themes of N. Gumilyov’s works about the war. He considered the victory of the spirit over the body to be the main condition for the creative perception of existence. In “Notes of a Cavalryman” Gumilyov wrote: “I find it hard to believe that a person who dines every day and sleeps every night could contribute anything to the treasury of the culture of the spirit. Only fasting and vigil, even if they are involuntary, awaken in a person special powers that were previously dormant.” The same thoughts permeate the poet’s poems:

The spirit blossoms like the rose of May.

Like fire, it tears through the darkness.

Body, not understanding anything

She boldly obeys him.

The fear of death, the poet claims, is overcome in the souls of Russian soldiers by the awareness of the need to defend the independence of the Motherland.

9. The theme of Russia in the works of Gumilyov.

The theme of Russia runs like a red thread through almost all of Gumilyov’s work. He had every right to say:

Golden heart of Russia

Beats rhythmically in my chest.

But this theme manifested itself especially intensely in the cycle of poems about the war, participation in which for the heroes of his works is a righteous and holy deed. That's why

Seraphim, clear and winged.

The warriors are visible behind their shoulders.

For their exploits in the name of the Motherland, Russian warriors are blessed by higher powers. That is why the presence of such Christian images is so organic in Gumilyov’s works. In the poem "Iambic Pentameter" he states:

And the soul is burned with happiness

Ever since then; drunk with joy

Both clarity and wisdom; about God

She talks to the stars,

The voice of God is heard in military alarm

And he calls his roads God's.

Gumilyov's heroes fight “for the sake of life on earth.”This idea is affirmed with particular persistence in art.desire for the “Newborn”, imbued with ChristiansChinese motives of sacrifice for the sake of the happiness of futuregenerations. The author is convinced that he was born. to the roarbaby tools -

...will be God's favorite,

He will understand his triumph.

He must. We fought a lot

And we suffered for him.

Gumilev's poems about the war are evidence of the further growth of his creative talent. The poet still loves “the splendor of lush words,” but at the same time he has become more selective in his choice of vocabulary and combines the former desire for emotional intensity and brightness with the graphic clarity of the artistic image and depth of thought. Recalling the famous picture of a battle from the poem “War”, striking with its unusual and surprisingly accurate metaphorical series, simplicity and clarity of figurative words:

Like a dog on a heavy chain,

A machine gun barks behind the forest,

And the shrapnel buzzes like bees

Collecting bright red honey.

We will find in the poet’s poems many accurately noted details that make the world of his war poems at the same time palpably earthly and uniquely lyrical:

Here is a priest in a cassock with holes in it

He rapturously sings a psalm.

Here they play a majestic tune

Over a barely noticeable hill.

And a field full of mighty enemies. Bombs buzzing menacingly and bullets singing, And the sky is filled with lightning and menacing clouds.

The collection “Quiver”, published during the First World War, includes not only poems that convey the human condition in war. No less important in this book is the image inner world lyrical hero, as well as the desire to capture the most diverse life situations and events. Many poems reflect important stages of the poet’s life: farewell to his gymnasium youth (“In Memory of Annensky”), a trip to Italy (“Venice”, “Pisa”), memories of past travels (“African Night”), about home and family ( "Old estates"), etc.

10. Gumilyov’s dramaturgy.

Gumilyov also tried his hand at drama. In 1912-1913, three of his one-act plays in verse appeared one after another: “Don Juan in Egypt”, “The Game”, “Actaeon”. In the first of them, recreating the classic image of Don Juan, the author transfers the action to the conditions of modern times. Don Juan appears in Gumilev's portrayal as a spiritually rich personality, head and shoulders above his antipode, the learned pragmatist Leporello.

In the play “The Game” we also have a situation of acute confrontation: the young beggar romantic Count, who is trying to regain the possession of his ancestors, is contrasted with the cold and cynical old royalist. The work ends tragically: the collapse of dreams and hopes leads the Count to suicide. The author's sympathies are entirely given here to people like the dreamer Count.

In “Actaeon,” Gumilev reinterpreted the ancient Greek and Roman myths about the goddess of the hunt Diana, the hunter Actaeon and the legendary king Cadmus - warrior, architect, worker and creator, founder of the city of Thebes. Skillful contamination of ancient myths allowed the author to clearly highlight positive characters - Actaeon and Cadmus, and to recreate life situations full of drama and poetry of feelings.

During the war years, Gumilyov wrote a dramatic poem in four acts, “Gondla,” in which the physically weak but powerful in spirit medieval Irish skald Gondla is depicted with sympathy.

Gumilyov also wrote the historical play “The Poisoned Tunic” (1918), which tells the story of the life of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. As in previous works, the main pathos of this play lies in the idea of the confrontation between nobility and baseness, good and evil.

Gumilyov’s last dramatic experience was the prose drama “The Rhino Hunt” (1920) about the life of a primitive tribe. In bright colors, the author recreates exotic images of savage hunters, their existence full of dangers, and the first steps towards understanding themselves and the world around them.

11. Gumilev and the revolution.

The October Revolution found Gumilyov abroad, where he was sent in May 1917 by the military department. He lived in Paris and London, translating oriental poets. In May 1918, he returned to revolutionary Petrograd and, despite family troubles (divorce from A. Akhmatova), poverty and hunger, he worked together with Gorky, Blok, K. Chukovsky at the World Literature publishing house, and gave lectures in literary studios.

During these years (1918-1921), the poet’s last three lifetime collections were published: “The Bonfire” (1918), “Tent” (1920) and “Pillar of Fire” (1921). They testified to the further evolution of Gumilyov’s creativity, his desire to comprehend life in its various manifestations. He is concerned with the theme of love (“About You”, “Dream”, “Ezbekiye”), national culture and history (“Andrei Rublev”), native nature(“Ice drift”, “Forest”, “Autumn”), life (“Russian estate”).

It is not the new “screaming Russia” that is dear to Gumilyov the poet, but the old, pre-revolutionary one, where “human life is real”, and in the bazaar they “preach the word of God” (“Gorodok”). The lyrical hero of these poems cherishes the quiet, measured life of people, in which there are no wars and revolutions, where

The cross is raised above the church

A symbol of clear, paternal power.

And the raspberry ringing buzzes

Speech wise, human.

(“Cities”).

There is in these lines, with their inexpressible longing for the lost Russia, something of Bunin, Shmelev, Rachmaninov and Levitan.In “Bonfire”, for the first time, Gumilyov’s image appears common man, Russian man with his

With a glance, a childish smile,

With such a mischievous speech, -

And on the valiant chest

The cross shone golden.

(“Mules”).

12. Biblical motifs in Gumilyov’s lyrics.

The title of the collection, “Pillar of Fire,” is taken from the Old Testament. Turning to the fundamentals of existence, the poet imbued many of his works with biblical motifs. He writes especially a lot about the meaning of human existence. Reflecting on the earthly path of man, on eternal values, on the soul, on death and immortality, Gumilev pays a lot of attention to the problems of artistic creativity. Creativity for him is a sacrifice, self-purification, ascent to Golgotha, a divine act of the highest manifestation of the human “I”:

True creativity, Gumilev argues, following the traditions of patristic literature, is always from God, the result of the interaction of divine grace and human free will, even if the author himself is not aware of this. Poetic talent, bestowed from above “as a kind of gracious covenant,” is an obligation to serve people honestly and sacrificially:

And a symbol of mountain greatness.

Like some kind of benevolent covenant

High tongue-tied

It is granted to you, poet.

The same idea is heard in the poem “The Sixth Sense”:

So, century after century - soon. Lord?

Under the scalpel of nature and art

Our spirit screams, our flesh is exhausted.

Giving birth to an organ for the sixth sense.

In recent collections, Gumilyov has grown into a great and demanding artist. Gumilev considered work on the content and form of works to be the primary task of every poet. It is not for nothing that one of his articles devoted to the problems of artistic creativity is called “Anatomy of a Poem.”

In the poem “Memory,” Gumilyov defines the meaning of his life and creative activity as follows:

I'm a gloomy and stubborn architect

Temple rising in the darkness

I was jealous of my father's glory,

As in heaven and on earth.

The heart will be tormented by flames

Until the day when they rise, they are clear,

Walls of the new Jerusalem

On the fields of my native country.

Never tired of reminding his readers of the biblical truth that “in the beginning was the Word,” Gumilyov, with his poems, sings a majestic hymn to the Word. There were times, the poet claims, when “the sun was stopped with a word // Cities were destroyed with a word.” He elevates the Word - Logos above the “low life”, kneels before it as a Master, always ready for creative learning from the classics, for obedience and feat.

Gumilyov's aesthetic and spiritual reference point is Pushkin's creativity with its clarity, accuracy, depth and harmony of artistic image. This is especially noticeable in his latest collections, which reflect the colorful and complex dynamics of existence with truly philosophical depth. In the poem-testament “To My Readers” (1921), included in the collection “Pillar of Fire,” Gumilyov is full of desire calmly and wisely:

...Immediately remember

All my cruel, sweet life, -

All my native, strange land

And standing before the face of God

With simple and wise words.

Wait calmly for His judgment.

At the same time, in a number of poems in the collection “Pillar of Fire” the joy of accepting life, falling in love with beauty God's peace interspersed with anxious forebodings associated with the social situation in the country and with one’s own fate.

Like many other outstanding Russian poets, Gumilev was endowed with the gift of foresight of his fate. His poem “Worker” is deeply shocking, the hero of which casts a bullet that will bring death to the poet:

The bullet he cast will whistle

Above the gray, foaming Dvina.

The bullet he cast will be found

My chest, she came for me.

And the Lord will reward me in full measure

For my short and bitter life.

I did this in a light gray blouse,

A short old man.

In the last months of Gumilyov’s life, the feeling of imminent death did not leave him. I. Odoevtseva writes about this in her memoirs, reproducing episodes of their visit to the Znamenskaya Church in Petrograd in the fall of 1920 and the subsequent conversation in the poet’s apartment over a cup of tea: “Sometimes it seems to me,” he says slowly, “that I, too, will not escape the common fate, that my end will be terrible. Just recently, a week ago, I had a dream. No, I don't remember him. But when I woke up, I felt clearly that I had very little time to live, a few months, no more. And that I will die very terribly.”

This conversation took place on October 15, 1920. And in January of the following year, in the first issue of the magazine “House of Art”, N. Gumilev’s poem “The Lost Tram” was published, in which he allegorically depicts revolutionary Russia in the form of a tram rushing into obscurity and sweeping away everything in its path.

“The Lost Tram” is one of the most mysterious poems, which has not yet received a convincing interpretation. In his own deep and original way, from the position of Christian eschatology, the poet develops here the eternal theme of world art - the theme of death and immortality.